Franz Kröger

Southern and Northern Bulsa:

Co-operation and Competition

1. Questions of definition

Although the terms Southern and Northern Bulsa are quite common in Northern Ghana, there is a

relative lack of clarity regarding their exact meanings. Can these terms be defined by virtue of

specific linguistic, genealogical or cultural characteristics?

Even a purely geographical designation is problematic. For example, Kadema, which belongs to

the Northern Bulsa (NB), is situated on a more southerly latitude than Bachonsa and Doninga which, in turn, belong to the

Southern Bulsa (SB).

To what degree there are any dialectical differences between the two groups has not been

explored. When I was working on my dictionary with informants from Wiaga and Sandema (NB),

all words or word forms which were unknown or less familiar to my co-operators were

designated as Southern Buli.

In the following list, the terms designated in the column as Southern Bulsa seem to be more common in the south while those of the NB-column are more common in the North.

Engl. SB (F = Fumbisi) NB (W = Wiaga, Sa = Sandema)

beating gabika naka

black ant ngiak ngangkering sobluk

burn luem ju (luem = to burn brightly)

bush-animals F sagi-dungsa W+Sa goai-dungsa

lies, n. F chieka W venta

shoulder F kpinkpaluk ngmangpaluk

When I asked other speakers, it was often revealed that both the alleged northern as well as

southern forms were used by Southern Bulsa. Furthermore, the alleged dialect boundary is not

identical to the new district boundary. Often in the south, the same forms or words are used in

Sandema (NB), while in Wiaga (NB) other linguistic variants are common.

bush-sprite, fairy: Fumb, Sandema and Chuchuliga:

chichiruk; Wiaga: kikiruk; Gbedema: either form

to be ill: Sandema and SB: yuagi; Wiaga: wiagi

to turn: NB and Gbedema: chiem; (other) SB and Chuchuliga: kiem

to pour: Sandema and Gbedema: nyoro; Kanjaga: ngoro

The roots of many Buli words can have an [a] in one group of speakers and an [e] or (rarely) an [i] pronunciation in other groups, for example:

evil: biam - biem

go: chang - cheng

rattle: jagsi - jegsi

saddle: kiari - kieri

mat (spec.): kpasik - kpesik

water: nyiam - nyiem

know: sabi - sebi

double bell: sanleng - sinleng

basketry strainer: yalung - yelung

In Sandema the [a]

- pronunciation prevails while in Wiaga and in large parts of the Bulsa-South

District it is the [e] - pronunciation.

Besides the phonemic differences, there appear to be differences in the semantics of some words.

All Bulsa distinguish between two types of bushland, the "nearby bush" (close to farmsteads) and

the distant bush inhabited by wild animals. In Sandema and Wiaga, the nearby bush is called sagi

and the remote bush goai. Wild bush animals are accordingly called goai-dungsa. According to

my information in Fumbisi, sagi seems to denote the remote bush and wild bush animals are called

sagi-dungsa. For locations outside the Bulsa area, only sagi is used by all Bulsa.

As concerns genealogy and descent, the four villages / towns of Sandema, Wiaga, Kadema and

Siniensi feel as though they are a unit, which they ascribe to the fact that they are descendants of

one original ancestor Atuga (cf. BULUK 7, 2013, pp. 69-88). Regarding their ancestry, the

Southern Bulsa like to refer to their connection with the vernacular Bulsa and hence sometimes

call themselves Buluk-bisa, although there are numerous surmised connections to the Atuga-bisa.

According to one tradition, Afim, the founder of Fumbisi (SB), is said to have come from the

royal Mamprusi dynasty in Gambaga, i.e. before the Mamprusi king moved to Nalerigu.

According to a local tradition, the founder of the Bachonsa (SB) village was an immigrant from

Wiaga (NB).

In the material culture, differences between the two districts are partly due to physio-geographical conditions. If in southern Bulsaland (as well as in the adjacent Mamprusi areas) thatched houses are the rule, in the north (as well as in the adjacent Kasena area), cylindrical houses with flat roofs are widely used. This is mainly due to climatic differences because a pitched roof can better withstand heavy downpours of rain.

Pottery is more common in southern parts than in the north, and this is certainly due to the abundant clay deposits, especially near Fumbisi. An extensive cultivation of rice in the south is possible because the flooded plains south of Fumbisi provide good conditions for rice cultivation.

The self-image as a distinct group within the entire Bulsa tribe seems to be more important than any distinguishing cultural traits. It is apparently decisive for a definition of the Southern Bulsa. Grouped under the name Southern Bulsa, they claim a separate identity from the rather strong feeling of togetherness of the Atuga-bisa. This may become apparent in the following two examples.

Bulsa migrants in Ghana’s big cities are used to founding "tribal associations" with a chief (kambon-naab) which sometimes break down into subgroups of people from separate Bulsa villages. In the 1970s (and perhaps in the present day) there were two Bulsa groups in Bolgatanga (the capital of the Upper East Region): the Atuga-bisa and Southern Bulsa. Each group had its own program of events and chose its own chairman/chairwoman. When taking part in festivals, a certain feeling of rivalry could even arise. But as soon as the interests of all Bulsa in Bolgatanga were affected, both groups worked together very closely and in a friendly manner.

When the Bulsa area still consisted of a single constituency, it happened

in the 1970s that in two

successive legislative periods the representatives elected for the Ghanaian Parliament came from the villages

of Sandema (NB) and Siniensi (NB), both Atuga-bisa. Then I heard from several Southern Bulsa

that in the next election only "Southern Bulsa" should be set up as candidates.

These examples will show that there is certainly a strong sense of identity in the groups of

Northern and Southern Bulsa.

2. Political, economic and social significance of the two groups

It appears that in earlier times the interests of non-Bulsa, especially of Europeans employed in the colonial service, referred more to the villages in the south of Bulsaland than to those of the north.

The importance of southern villages in the 19th century is reflected in many events and facts. The slave-raider Babatu, leaving his main headquarters in Seti (Burkina Faso) in the late 1890s, established his camp at Kanjaga. Babatu’s great adversary, Amaria set up his camp at Bachonsa. They chose these two locations because both villages met the condition of being able to supply large crowds. Bachonsa and Kanjaga are also the first Bulsa villages that appear on a European map (see Buluk. 4, p. 23).

R.S. Rattray, the colonial administrator and anthropologist, dedicates just 5 pages to the Bulsa in

his two-volume work on the "Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland" (1932). He discusses the history

and culture of Kanjaga on 2 pages, but hardly deals with other Bulsa villages.

Although the term "Kanjagas" for all Bulsa was based on an error, this name remains for a certain

time after the discovery of the error, since Kanjaga was one of the most important or even the

most important Bulsa village. Even in the middle of the 20th century, villages of the Southern

Bulsa area appear on maps more often than the four villages of the Atuga-bisa. In 1968/69 the

“Survey of Ghana” published a series of thematic Ghana maps. On the nine maps in my

possession, the following Bulsa villages were recorded: Kanjaga: 8 (times), Doninga: 8,

Chuchuliga: 7, Kadema 7, Wiesi 7, Kunkwa (now Northern Region): 7, Uwasi: 4 times. Sandema,

Wiaga and Siniensi were recorded on none of the maps. These maps do not reflect the conditions of

the 1960s, for in 1969 Sandema, the seat of the Paramount Chief, and Wiaga were

certainly of greater political and economic importance than Doninga, Wiesi or Uwasi.

The importance of the north-eastern half of the Bulsa area increased considerably with the beginning of the 20th century while villages of the South Bulsa diminished in importance. Typical of this development is the fate of the chieftaincy of Vari (Vare), as it can be seen on old maps, in the diary entries of colonial officers and - in recent times - in the data present in the Ghana Population Census.

1907 first mention of Vari in the Navrongo Record Book (visit of SD Nash)

1918 Cardinall, a British officer and, at the same time, one of the first authors who

published about the Northern Territories is visiting Vari

1920 influenza or C.S.M. [Cerebrospinal Meningitis?] in Vari

1925 16 compounds in Vari

1930 C.N. Nunn in Vari: Hookworm disease

1931 G.E. Bernard visiting Vari (with 9 compounds, before: 23 compounds)

1936 Dr. H. C. Waters (?) in Vari: Hookworm disease

1937 8 compounds in Vari

1947 M. H. Hughes in Vari: 5 compounds with 30 inhabitants

1948 Population Census: 4 compounds, 35 inhabitants

1960 air-photos as the foundation of the topographical map 1: 50,000: 2 compounds

1970 Ghana Population Census: 3 compounds, 9 inhabitants

2000 and 2010: Ghana Population Census: no entries about Vari found

There was perhaps a time when Kanjaga and Sandema strove for a certain hegemony within the

Bulsa area. The election of the Paramount Chief in September of 1911 revealed who was the

winner and who was the loser in this competition. The two candidates were Ayieta, the

Sandemnaab, and the chief of Kanjaga. Perhaps it came as no surprise that the Atuga-bisa, Wiaga,

Siniensi and Kadema voted for the Sandemnaab while, of all the Southern Bulsa, only Fumbisi

voted for the Kanjaganaab. The other present chiefs of Doninga, Gbedema and Uwasi abstained.

After this election the debate over who reigned supreme throughout the traditional Bulsa area was

settled and has remained so until the present. What were the reasons for the rise of Sandema and

the decline of Kanjaga? Sandema certainly benefited from its victory over Babatu (around 1896)

in which it took over the command of an army where many South Bulsa refugees found a place.

Sandema’s close proximity to the headquarters of the British in Navrongo and the generally good

co-operation with the colonizers was beneficial for Sandema, too. In my opinion, however, the

decisive factor in the decline of many Southern villages and the consequent changes in the power

relations of Bulsaland was probably due to the displacement of the main trade-route passing

through this area.

|

|

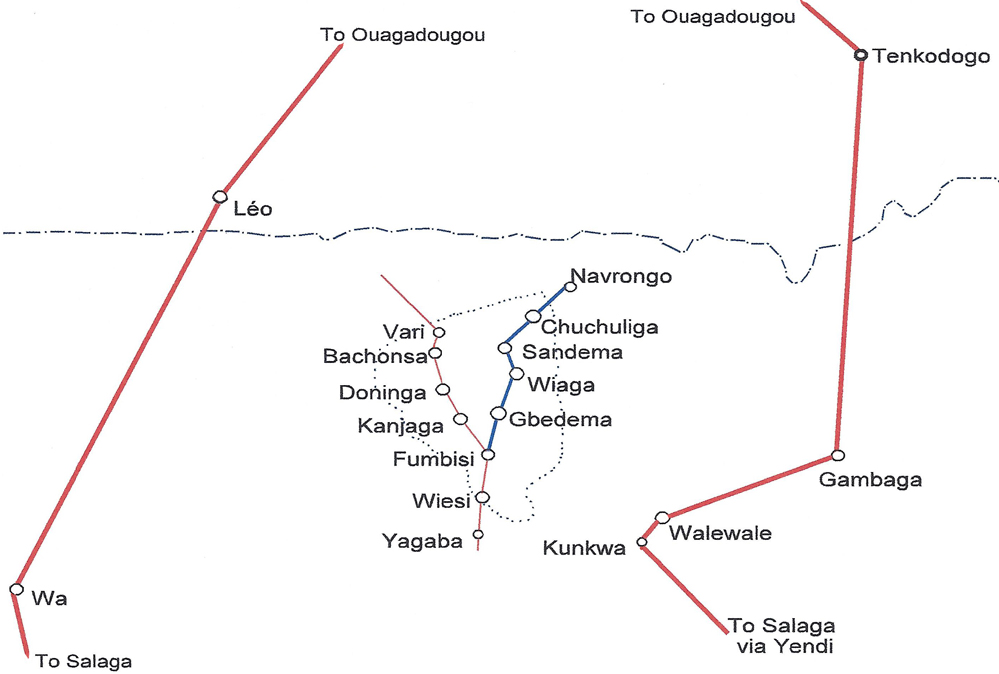

Trade routes: the two old and important routes (bold red lines); the old secondary route running through the Bulsa area (thin red line) and the new trade route and arterial traffic road (blue lines). |

Before the occupation of northern Ghana by the British, two major north-south trade routes

crossed north Ghana. These routes included "the eastern one by way of Salaga, Tamale (or Yendi)

to Kunkwa (the Bulsa village), Wale Wale and from there to Gambaga or even farther to the north into the present Burkina

Faso. The western route ran via Kumasi and Bole to Wa and even further on to Léo in Burkina"

(BULUK 3, p. 29).

A secondary trade route coming from the present-day Burkina Faso passed Vari, Bachonsa,

Doninga, Kanjaga, Fumbisi, Wiesi, Yagaba and went on further to the south, raising the

prosperity of all villages and towns it passed.

A clear change occurred when, at the Berlin Congress (1888) and finally in 1898, the boundary

between the British and French colonial claims was set at approximately the 11th latitude. The

free exchange of goods, particularly between the Southern Bulsa villages with trading centres in

the French territory, became severely restricted.

At the same time, a new trade route developed: from Navrongo to Sandema, Wiaga, Gbedema,

Fumbisi, Wiesi, Yagaba and on to the southern commercial centres. This change negatively

impacted those Bulsa villages situated on the ancient trade route. Kanjaga in particular lost its

importance while Fumbisi, which had previously stood in the shadow of Kanjaga (see election of

the Paramount Chief 1911, BULUK 7: 100-102), greatly increased in importance because it was

also situated on the new trade route.

Since the southern route from Fumbisi to Wiesi had been almost impassable for motor vehicles for

a long time, Fumbisi also benefited from its new position as the end point of the north-south road.

Many farmers and small traders from a fairly wide area visit the large Fumbisi market held every

six days. For example, for the inhabitants of the Koma villages of Nangruma, Senta and Bayeba,

Tiging Fumbisi is the only market where they sell their agricultural products and purchase

household goods (for example, clay pots) and luxury items.

When the large Bulsa district was split into two parts on June 7, 2012, there was no question that

Fumbisi and not Kanjaga should be the capital of the new Bulsa South District.

The division into two Districts was probably welcomed by the vast majority of Bulsa, albeit not

with much enthusiasm. Some educated young people doubted whether this division would really

lead to more development in both parts. Today the inhabitants of the whole Bulsa area accept the

division as a fact that should not be discussed any longer.

|

|

|

Present Fumbisi District Assembly and DCE's office.

|

|

|

Right: Fumbisi Districts Assembly block under construction |

A supreme Sandema has survived because the Sandemnaab

remained Paramount Chief of all

Bulsa and the village chiefs (divisional chiefs) of the Bulsa South District still have to come to

Sandema to be elected and installed there. But it is already widely rumoured that the Fumbisi

chiefdom and possibly some others (e.g. Wiaga) will be raised to the rank of a paramountcy. But

even if this happened, the feeling of togetherness of all Bulsa would not be affected.

As in earlier times, the displacement of a trade route led to major changes in terms of wealth and

socio-political significance in several southern Bulsa villages. The improvement of the road

between Sandema and Fumbisi which, in turn, is connected with roads to Kanjaga and other

places might in the future further the development of the South District Bulsa immensely.