Sandemnaab Azantilow in 1973

Franz Kröger

Kunkwa, Kategra and Jadema: The Sandemnaab’s lawsuit

|

|

Sandemnaab Azantilow in 1973 |

Political boundaries, which cut through the territories of peoples or ethnic groups, have often led to tensions and bloody conflicts in the history of the world. But even in peaceful daily life, they may cause alienation between family members or friends who live on different sides of the boundary. Any contacts are complicated by inconvenient bureaucratic formalities.

In Africa colonial boundaries, which later defined the new states, were created at the whims of the colonial powers. As the topographical conditions of the land were only roughly known to them, the borderlines often coincided with rivers, and if there were no suitable rivers, geographical degrees of latitude or longitude were declared political boundaries. Thus, the British Gold Coast Colony and its hinterland, which in 1957 was to become modern Ghana, were defined by rivers flowing from north to south and by the 11th degree of latitude, which over long distances forms the border between Ghana and Burkina Faso. Thus, Ghana took the shape of a nearly rectangular form.

Some ethnic groups and kingdoms suffered more than others from the fragmentation of their territory. The greater part of the Dagomba kingdom, along with the town of Tamale, became British, while the western part with Yendi, the traditional capital, was placed under the German colonial government. The tribal areas of the Dagara, Sisaala and Kasena were divided up between the British and the French.

Making the western part of Togo a British mandate after the First World War and combining it with the Gold Coast after a referendum on May 5th, 1956, meant a reunification for the Dagomba. But at the same time the territory of the Ewe was partitioned between Togo and the Gold Coast/Ghana.

Boundaries of Districts or Regions which cut through tribal areas, although sometimes regarded as less problematic and painful, can also lead to conflicts. When in 1960 the Upper Region was separated from the Northern Region of Ghana, the new boundary cut the tribal area of the Koma into two parts. The larger part remained in the Northern Region, while the villages of Tantuosi and Bayeba Tiging became part of the Upper Region (and in 1984 of the Upper West Region).

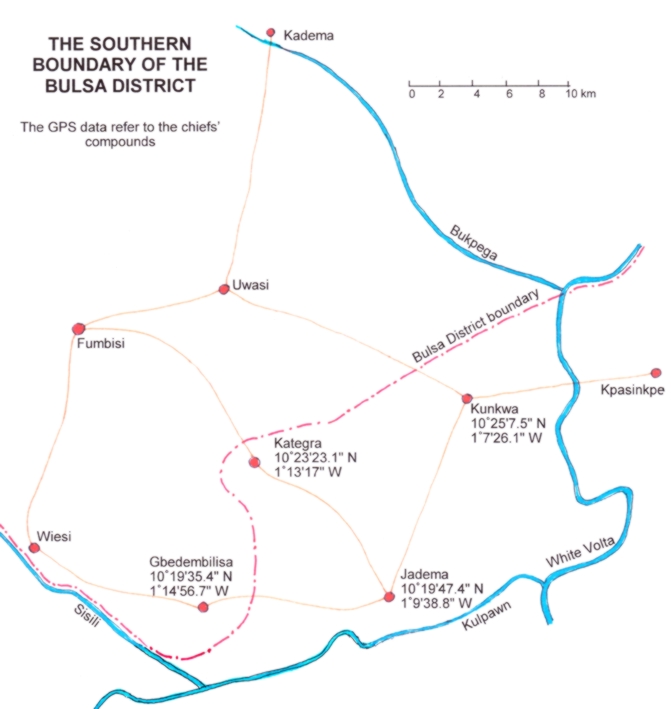

After Ghana’s independence in 1957, quite a number of intertribal conflicts took place in Northern Ghana. It appears to be extraordinary that the Bulsa have never been involved in such conflicts (Cf. Awedoba 2010, the best and most extensive compendium about all conflicts in Northern Ghana). It is up to experts on conflict research to find the reasons for this. In my opinion the most important factor for this intertribal peace is the fact that the Bulsa District is one of the few districts in Northern Ghana that is almost exclusively inhabited by one ethnic group and that the political boundaries of the district and the paramountcy coincide to a very great extent with the distribution of Buli speaking people. Apart from some Kantussi (Yarisa) merchants, especially in Sandema and Fumbisi, who adopted Buli as at least their second language and some nomadic Fulani herdsmen who usually build their temporary settlements outside the Bulsa villages, the only exception of the statement about the coincidence of political and ethnic boundaries are three Bulsa villages outside the Bulsa District: Biuk, Kunkwa (Kunkuaga) and Kategra.

In this article the Sandemnaab’s attempt to the three villages into the Bulsa District will be

described and analysed.

In this article the Sandemnaab’s attempt to the three villages into the Bulsa District will be

described and analysed.

On April 10th, 1951, Azantilow, Paramount Chief of the Bulsa in Sandema, sent a letter written by a Bulsa Native Authority Officer to the Chief Commissioner of the Northern Region in Tamale. The main purpose of this letter was to take legal action against the following chiefs and headmen in court:

1. Aninlik, chief of Kategra

2. Anabil, chief of Kunkuaga [Kunkwa]

3. Ajuik, chief of Jaadema

4. Headman of Buiyeng

5. Headman of Ngaaba

6. Headman of Gyambaliok

The point of contention was formulated as follows:

The above mentioned chiefs and Headmen of the six villages are living on the Builsa land which lie[s] on the West side of the White Volta River and are Builsas and do not pay their tribute tax to the Builsa Native Authority. Hence, I am taking the said action, as it is well known that the White Volta River is [was] the boundary before the coming of the white man.

In the negotiations preceding the lawsuit, the historical sources documenting the political position of Kunkwa and Kategra were examined. They are often confusing and contradictory, and most of them contain no information about their author or the office from which they were issued. Nevertheless, a great part of them will be rendered here without any changes or long comments. (Some obvious spelling mistakes and the modern orthography of some names are interpolated in square brackets; for more sources from the Tamale Regional Archive see:

http://www.kroeger1937.homepage.t-online.de/Materialien/Tamale-Archiv.htm (a chapter of the website www.ghana-materialien.de )

26/5/1906

(KUNKWA) ...The population of Kunkwa consists of a large proportion of Mamprusis, which is accounted for by its being on the borders of Mamprusi country. These [There?] are no towns under Kunkwa. The town is under the chief of Passinkwia [Kpasinkpe]. The town is on the main caravan route from Moshi Country to Salaga and Kintampo. The Chief Fetish man is Atombi. The fetish is called "Wallsi". The fetish place is some rocks to the North side of the town. The following are the Sections and Headmen.

Section Yalbilinsa (Chief) Headman Abubina

Kunsesa Atubili

Twisiensa Tindana

Gandema Atumbi

It is impossible, at present, to estimate the account of labour that may be expected, as the town has been hence without a Chief for a long period and the people appear to he [be?] under the control of their Headmen. (Sgd.) A.M. Henry, Capt. D.C.

19/9/11

...Kunkwa follows Passankwa [Kpasinkpe] - Nalerigu. Chief Aparanga very old and likely [not?] to live many days. The fetish man is Adju and he receives a fowl after a good ha[r]vest from all landowners.

15/6/1912

(altered in March, 1917) N.B. Nalansa or Katigri, between Kunkwa Bedema [Gbedema]. Godemblisi [Gbedembilisi] follow Kunkwa. The whole country between these two places is a lake in the rainy season.

23/4/15

Visited [Kunkwa]. Chief has no complaint. He says however that he does not wish to follow Sandema. I can fined [find] not record of his being told to do so and a note of September, 1911 says he follows Passinkwere, and I do not see why this should be upset. Order in future will be sent through the Chief of Navaro [Navrongo].

23/4/15

Chief of (Katila) Katigri [Kategra], a small place under Kunkwa and who was made by Kunkwa, complains that his people have never followed him since his appointment. He can give not satisfactory reason for not reporting to the commissioner during the last three years. Kunkwa told to enquire into it. (Sgd.) ???

27/12/17

.... C.N.E.P. [Commissioner of the North Eastern Province?] and D.C. [District Commissioner] visited here [Kunkwa?] and found the Rest House and compound in a very bad condition. The Chief complains that his people will not follow him. The Chief of Sandema [Afoko] followed us here and is anxious that Kunkwa should be put under him. The majority of the people speak Kanjarga [Buli], but say that they are Mamprusis. The C.N.E.P. says, before taking any steps in the matter he will consult with the chief Passankwere, who appoints the Chiefs of Kunkwa. (Sgd.) L.C. (D.C.)

30/12/17

A letter is received from the C.N.E.P. at Passankwere in which he states that before our occupation of the country and before the raids of Babatu, the Chief of Passankwere, with the authority of the Na of Mamprusi had power to appoint Chiefs in the following villages: - Kunkwa, Iuwase [Uwasi], Fambisi [Fumbisi], Kanjarga, Kadema, Seniessa [Siniensi], Wiaga, Sandema, Doninga and many other villages in Mamprusi country. When one WURUME was Chief of Passenkwere he appointed one of his sons Chief Kunkwa, whose sons were made chiefs of Kanjarga, Wiaga, Sandema and Seniessa [see endnote (1)]. This was previous to Babatus’ raids. These men were of course Mamprusis and were the ancestors of the present Chiefs of those villages who now call themselves Kanjargas. Some of these people have now affected the Kanjarga markings and language from residence [residents?] in the country and intermarry with Kanjargas, but the present Chief of Sandema (Afawko [Afoko]) himself is an example of Mamprusi markings, shewing his Mamprusi descent.

The Chiefs of the above mentioned (now recognised as Kanjarga) villages up to the coming of Babatu, were not only appointed by the Chief of Passankwere, but approached him through the Chief of Kunkwa for confirmation in their appointments as chiefs; consequently, if this statement is correct, to appoint Sandema now over Kunkwa would be an upheaval of all Native traditions and customs.

(Sgd.) B. Moutray Read, C.N.E.P.

5/6/20

Visited [Kunkwa]. The Chief of Sandema complained that these people did not follow him. I warned the Chief's son to go pay his re[s]pect to Sandema forthwith. The Chief of Sandema is trying to make much of nothing, they agree but perhaps [sic] the old chief not willingly.

25/11/20

Visited [Kunkwa] with Chief of Sandema, held an election for a new Chief and Akwabil was elected with a majority of 55. Natorma the chiefs son being the only opponent who had a following large enough to be considered. (Sgd.) George B. Freeman. D.C.

9/11/26

Chief (of Sandema) complains that 9 more compounds have moved over to South Mamprusi. Sipriani (Cypriani) says that this was report[ed?] about April last. Chief says others are preparing to go - reason - too much work in Navaro, which is nonsence [nonsense]. Given a talking to and orders reiterated that people must not move from one district to another without first obtaining permission. Took list of names of the migrants for reference.

Letter No. 173/3/18 of 4th March, 1920.

Captain No. 5/1920 of 4th March, 1920

Wash’s letter 25/3/18 copy available in D.C. Office Navrongo. The Court can ask for the Produce in Court.

Kayare Chief of Passankwaire, Apetadina Achief [sic] Aba. Caused Kayare destoolment

Kunkwa

JUDGEMENT

I. The claims of Kayare chief Passankwire and of Petadina, styled Chief of Aba to the overlordship of certain villages situated on land lying to West of the Right Bank of the white Volta River are baseless.

II. The Boundary between the Passankwaire lands and those under the chief of Sandema is the white Volta River, with equal fishing and other rights to the inhabitants of both district.

III. The Title "Chief of Aba" ceases to be borne by any Passankwaire chief.

C. H. Armitage, C.C.N.T.; Gambaga

The impudent [impudence] of Kayare to deceive the chief Commissioner and I may add his paramount chief who was visiting Passankwaire for the first time and was in no way to blame in the matter, cannot be overlooked and I have decided to destool him, but have referred the matter to era and his sub-chiefs in order to ascertain their opinion of Kayare’s conduct. etc. etc.

----------

On February 27th, 1952, the hearing took place with P.W.C. Dennis as the President of the Chief Commissioner’s Court (Tamale). The plaintiff was Azantilow, and the defendants were 1. Nayeri, Mamprusina, 2. Ajuik, Chief of Jadema, 3. Aninlik, Chief of Kategra, 4. Anabil, Chief of Kunkwa.

The minutes of the judicial proceedings explain why the plaintiff’s claims failed:

As "all the claims of the plaintiff" were "dependent upon his claim that the White Volta is the boundary between the land of his tribe and of the first defendant’s tribe," this was the "main issue to which the attention of the court" had "been directed."

After declaring that it is not against the law and former ordinances for one chief to claim land from another, the court had to consider whether the plaintiff’s claims were based (1) on previous decisions and (2) on history and custom.

As concerns previous decisions (1), the court stated that no decision had been given which was in any sense a judicial one. In 1920 officers had investigated the matter in the area concerned, but there was not "anything to show that the persons who investigated the matter directed their minds to the land law concerned," and "they were more concerned with administrative arrangements." (p. 40)

The court also examined whether the plaintiff’s claims were based on history, custom and language. It was stated that the "swearing of alliance [allegiance?] to a certain Chief or the speaking of a certain language (2) or the carrying out of certain practices by groups of people is not conclusive evidence of where title to land lies", although "in conjunction with history, an association of language, practices and customs...is evidence of value in deciding where title to land lies..."

Unfortunately for the plaintiff, two of his four witnesses did not seem very reliable when cross examined. One of them "was likely to be a man with a grudge, as he had been fined twice by one of Nayeri’s courts."

When I (F.K.) interviewed people of the Sandema District as well as those in Kunkwa and Kategra, all of them declared that the reason for the separation of those villages was only the hard work they had to do in Navrongo. In the minutes this argument made by the plaintiff is apparently not given very much weight by the British lawyers: "According to the plaintiff’s evidence, the dispute... arose because the people of the villages did not want to work at Navrongo... The court finds it hard to believe, however, that there was not some stronger force..."

As concerns "the historical side of the plaintiff’s case," it was admitted that at times there had been "a close association between the three villages...and the Chief of Sandema." The minutes continue: "It has not, however, been shown how far this was voluntary, but it is clear that Government strongly favoured the arrangement and brought pressure to bear to prevent any breaking away from it."

Although the plaintiff sought to show that the language of his people and that spoken in the three claimed villages is Buli, the witnesses of the defendants declared that both the Buli and the Mampuli [Mampruli] languages are spoken on each side of the river.

In addition, other arguments made by the plaintiff, e.g. concerning circumcision, tribal markings, funeral customs and intermarriage, did not provide sufficient evidence that the three villages were Bulsa. Besides, it was the main concern of the court to find out whether the plaintiff had established his case that the boundary was the White Volta.

Finally the court came to the following verdict:

In the evidence brought before the court, it has not been shown that the area of the Builsa tribe extends right up to the river and ends there, nor has it been shown that the river is the boundary of the Mamprusi tribe. It has not been proven that there was a boundary on the White Volta from time immemorial, nor has it been shown that the ties of the people from the villages of Giadema, Katigiri and Kunkwa are with the Chief of Sandema. In fact, the evidence shows that these villages have strong ties with the Wuruguna and through him with the Nayeri, the first defendant.

This meant that the Sandemnaab had lost the case.

As the plaintiff was dissatisfied with the decisions of the Chief Commissioner’s Court, he appealed to the West African Court of Appeals in Accra. In his filing, 16 grounds were listed. Most of them are repetitions of the former claims (e.g. that the White Volta is the boundary of the Bulsa area) or criticisms of the decisions of the court (e.g. that the refusal to work in Navrongo was a true cause of separation); the decision of Armitage in Gambaga on March 4th, 1920 (see sources above), was a judicial one; there was no evidence to support the suggestion of a grudge of the plaintiff’s fourth witness, etc.). To my view the main problem of the conflict as negotiated in the lawsuit was the plaintiff’s claim of land. The fact that the three village do not practise [male] circumcision (like the Bulsa and unlike the Mamprusi) and that they have the same tribal marks as the Bulsa, etc. does not justify a claim of land. The crucial point is whether Sandema’s overlordship over the villages includes a superior title to land (ground 3) or, as it is formulated in ground 4, whether it is true that the swearing of allegiance to a chief means that the chief also has a title to the swearer’s land.

The Tamale Court had already admitted in vague formulations that there were some political ties between the three villages and Sandema (p. 41): "It is clear that when the second, third and fourth defendants took office, a big part was played by the Chief of Sandema" and " ...it is clear that there has at times been a close association between the three villages...and the Chief of Sandema." But the court had denied that these justified any claims of land. Probably, at the time of the two lawsuits (1952) the knowledge about the interdependence of political overlordship and a title to lands had not yet been elaborated sufficiently. I wonder whether this problem has been completely solved today. When the Tamale court issued commentary on the judgement, it used terms like "feudal society." The term "feudal" was adopted from European history and has a very close and specific meaning (cf. lat. feudum, sth. that is lent to sb.; it is associated with certain services of the vassal to his feudal lord), and it is to be suspected that a very Eurocentric view entered the discussion here.

As the plaintiff did not bring forward any really new arguments, it was not surprising that his complaint was dismissed by the Court of Appeals.

Today, after more than 60 years, the question regarding which paramountcy and district the three villages belong to is still very topical, but the preconditions for a solution of the problem have changed. The people of Kunkwa and Kategra are no longer disinclined to be integrated into the Bulsa District.

When I visited Jadema in 2011 the chief, Alhaji Nasigri Sahku, who could not speak Buli, told me that Jadema is a Mamprusi village. According to him Bulsa (together with Mamprusi) are only living in the section of Suua with the two subsections of Nansaari Gbenni and Tindaanpoa Gbenni.

The boundary between the three villages and the Bulsa District became a regional boundary on July 1st, 1960, when the Upper Region was separated from the Northern Region.

The meaning of regional boundaries was described by R.B. Bening thus:

The regions, as major territorial divisions of the country, are not merely just convenient units of administration but political entities... The exercise of jurisdiction by traditional rulers across regional boundaries would cause resentment, unrest and seriously compromise the political identity and corporate nature of the regions. (1973, The Regional Boundaries of Ghana 1874-1972, Research Review, 9,1, p. 51)

This would mean that for any changes in the status of the three villages (e.g. placing them under the jurisdiction of the Sandemnaab), regional boundaries would have to be changed. Bening, however, does not completely exclude any alterations in the course of these boundaries: "Wherever possible, regional boundaries should be recast to coincide with limits of traditional allegiance and thus stabilize relations between the various communities in the regions."

Notes

(1) This information might be influenced by the old Bulsa legend that one Atuga came from Mamprusiland and his sons founded the Bulsa villages of Kadema, Sandema, Wiaga and Siniensi. In 1978 the Sandemnaab (Azantilow) told me that the origin of all Bulsa is situated between Kpasinkpe and Kunkwa and that near the village of Tangdaga you can still see the abandoned settlement with a lot of ancient graves.