Franz Kröger

Who Was This Atuga?

Facts and Theories on the Origin of the Bulsa

INTRODUCTION: In the main part of this essay, different versions of the myth about Atuga, the first Mamprusi immigrant, and the forefathers of the indigenous population will be rendered, analysed and compared. Which of these versions is authentic or which elements of the stories are true is difficult to decide today. If one version differs very much from all of the others and if these differences justify some privileges of the informant or informing group, some suspicion should be substantiated.

Abbreviations: D.C.: District Commissioner; C.C.N.T.: Chief Commissioner of the Northern Territories; R.H.: rest house; NAG.: National Archives of Ghana (Accra)

1. EIGHT VERSIONS OF THE ATUGA MYTH

1.1 Version 1 (v1)

When I started collecting data on the early history of the Bulsa, I asked several educated people of different ages what they knew about Atuga, the legendary founder of one part of the Bulsa population. I was surprised that all the stories told to me by educated people resembled each other, especially as concerns the episode of Atuga naming his four sons. When asked for the origin of their information, nearly all mentioned the small booklet, Legends of Northern Ghana (1958), by D. St. John-Parsons, an educational officer and secondary school teacher. In the 1970s this booklet was available in most school libraries and was even in the possession of some of the teachers and students. St. John-Parsons’ informants for the chapter "Atuga, the Founder of the Builsa" (p. 38-40) were three Bulsa boys, probably his pupils, who, according to R. Schott (1977:146), "could have had only a rudimentary knowledge of the oral tradition.".

(John-Parsons p. 38): Atuga was the son of a Nayire [Mamprusi King]. He quarrelled bitterly with his father, and was banished from the Mamprusi state. With some followers Atuga wandered to the west...

He passed through Naga and at last found a good place for a farm [in Bulsaland]...

(p. 39) ...in time Atuga married the daughter of a man named Abuluk.

One day Atuga decided to name his sons, so he killed a cow and called the boys. When the cow had been skinned and cut up he told each boy to take the piece of the cow he liked best.

Atuga named his four sons according to these chosen pieces of the cow. The eldest chose the shin (karik) and was named Akadem. The second son chose the thigh (wioh) and was named Awiak. The third son chose the chest (sunum) and was named Asandem. The fourth son chose the bladder (sinsanluik) and was named Asinia. After Atuga’s death "Akadem stayed on his father’s farm and gave it his name [Kadema]." The three others founded the villages of Wiaga, Sandema and Siniensi.

Only a few population groups who lived in the Bulsa area before Atuga are mentioned in Parsons’ text (p. 40): "They are the Gbedemas, the Yiwasis, the Bachonsas and the Wiesis, who together [with the Atugabisa] form the Builsa tribe."

1.2 Version 2 (v2)

Starting in 1966, R. Schott collected data on the history of the Bulsa "in 64 interviews, eight of which were given by the Paramount Chief of the Bulsa and Sandem-naab, Mr. Azantinlow" (1977: 147). During his second stay in 1974/75, he supplemented the traditions he had collected before in 40 more interviews.

The following text of Azantinlow’s account on Atuga was adopted from R. Schott’s publication (1977:149f.) with his compilations:

Long, long ago our forefathers (lit. our fathers’ fathers) went out from Nalerigu [the capital of the Mamprusi kingdom] and came to settle [here]. Formerly all of us [i.e. we, the Bulsa, and the Mamprusi] lived at one place, but then our fathers and their fathers fought with one another.

The reason why we and the Mamprusi fought with one another was that our forefather’s wife became pregnant and they thought that the woman would give birth to a ‘good’ child [with magic powers], and therefore they seized the pregnant woman, killed [her] and tore the child out [of her womb]. This was the reason why we then fought with one another and shot at one another with arrows. They came to think that the woman would give birth to a male being or something that was ‘good.’

The woman was ATUGA’s wife. ATUGA came to be a real (good, generous) man; they [the Mamprusi] then wanted to drive him away, but they did not know how they should do this. They then thought that if they killed the woman, they would come to fight with ATUGA and subsequently drive him away...

At the time when our forefathers [i.e. Atuga and his relatives] and the forefathers of the Mamprusi came to fight with one another [against each other], they [the Mamprusi] surrounded ATUGA and all his followers, held them in their midst and they wanted to capture him. He [Atuga] then mounted a horse and it rose upwards, took him and went to land on the Gambaga scarp. The foot-prints of the horse are impressed at that place up to this very day. He had a spear; its mark is also left at that place up to now. The holes [of these imprints] rest still at that place. These things actually exist; people go there to see [them]... He then stayed on the scarp and assembled all his followers and then went on to the Bulsa country and became a Bulo.

1.3 Version 3 (v3)

In Wiaga-Kom, whose inhabitants claim not to be descendants of Atuga, R. Schott interviewed an old man called Awunchansa from the section of Kom on January 7th, 1967. He complained bitterly about the Atugabisa, whom he considered usurpers. The researcher was given the following story about Atuga:

AWIAGH’s father was ATUGA; ATUGA’s father was ANGURIMA. [In their original homeland among the Mamprusi] there was some misunderstanding and ATUGA and his father were driven away. ATUGA’s father had wronged his father. ATUGA’s father was driven away and he came here, but he [F.K.: Atuga?] had no child. He came here and married a daughter of the people already living here and had his children (sons). The people ATUGA met were the Kom (Komdem). They were Bulsa... (Schott 1977:157)

1.4 Version 4 (v4)

Olivier/Ollivant [see "Note"], assistant District Commissioner (DC) of Navrongo in the early 1930s, was most interested in local history and on nearly every visit to a Bulsa village, he asked questions about their original myths and migratory myths (Cf. also NAG: ADM Series, Diaries). He was told the following story about the Mamprusi immigrants (informants and places of inquiry are not mentioned by the author):

A man of the Na Mamprussi’s family, ATUGA by name, quarrelled with his brothers, one of whom took his wife from him by force. On appealing to the others he got no support and, enraged, he left the place. He wandered through the Tong Hills and became acquainted with the fetish there. He made a sacrifice asking the fetish to find him a good home [and] to give him a large family. From there he went to a place (now non-existent) situated between the villages now called Sandema and Wiaga. He met there a man called AWULONG who spoke a language called BULI... These two became friends but Atuga, being a Mamprussi, was not a dog-eater. Awulong was, and he asked Atuga to join in eating a dog to celebrate his arrival. Atuga agreed and swore an oath to this effect:

"Now [that] I have eaten a dog I am no longer a Mamprussi and none of my descendants shall ever set foot in Mamprussi country again on pain of death."

This story has been handed down to the present day and no descendant of Atuga has ever been into Mamprussi unless ordered to by the British to [attend] a conference at Nalerigu or for some other reason. The incident at the Tong fetish has been kept up however, and representatives of the fetish priests come every year to collect the sacrificial cow, etc. from Sandema.

To continue the story: Atuga married a daughter of Awulong and had four sons: ASAM, KADEM, and WIAG and SENIEH. He then went and settled at what is now Kadema, leaving ASAM behind at SANDEMA, taking KADEM with him and leaving WIAG at what is now called WIAGA. Atuga died at KADEMA and KADEM remained there and formed the place. SENIEH went to what is now SENIESSI and ASAM to SANDEMA (Ollivant 1933:2).

Note: The author of the typescript of 1933 appears in the spelling "Ollivant". In the files of the NAG (National Archives of Ghana, Accra) I could read clearly his signature as "Olivier". As in both sources the author mentions his experience in Kunkwa on August 17th, 1932, Ollivant and Olivier must be the same person. Nevertheless, inthe following text I will use "Ollivant" when quoting from the typescript, "Olivier" when from NAG. - Cf. also C. Lentz 1998: 307: Lawra-Tumu District Commissioner Olivier...(1931).

1.5 Version 5 (v5)

When Olivier (DC) was in Kunkwa on August 17th, 1932, he happened to meet Pitadina, the Ex-Chief of Passankwia [Kpasinkpe] who gave him information about early migrants from Mamprusiland:

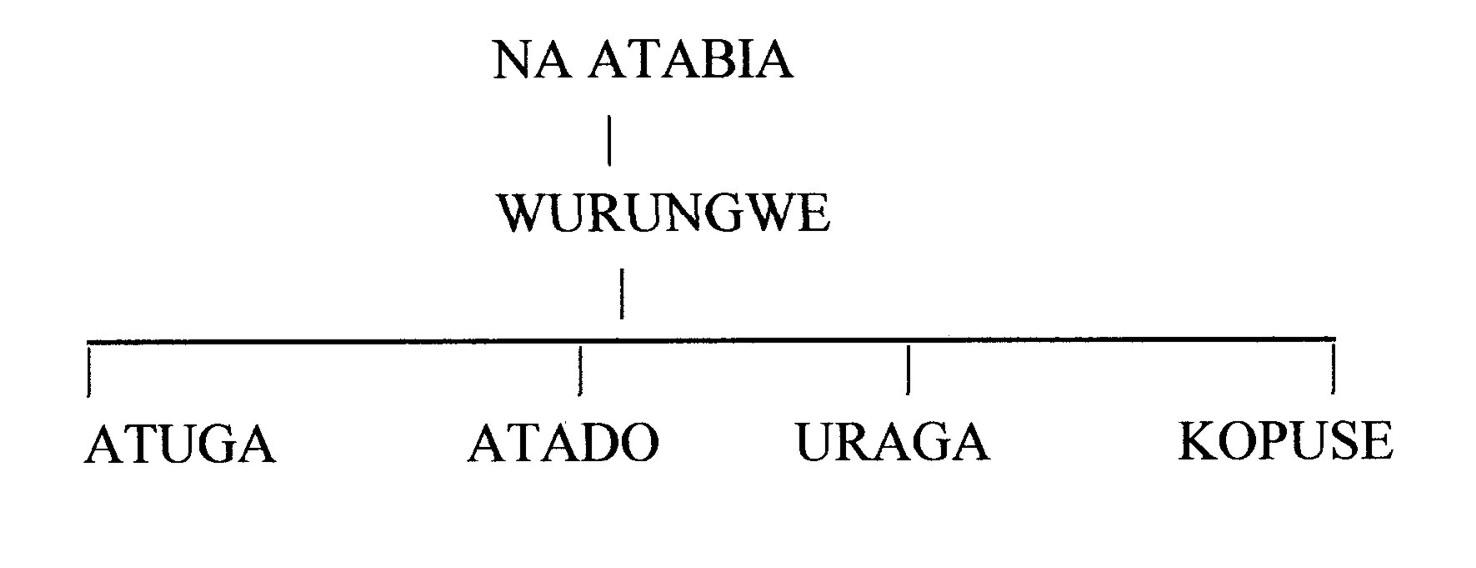

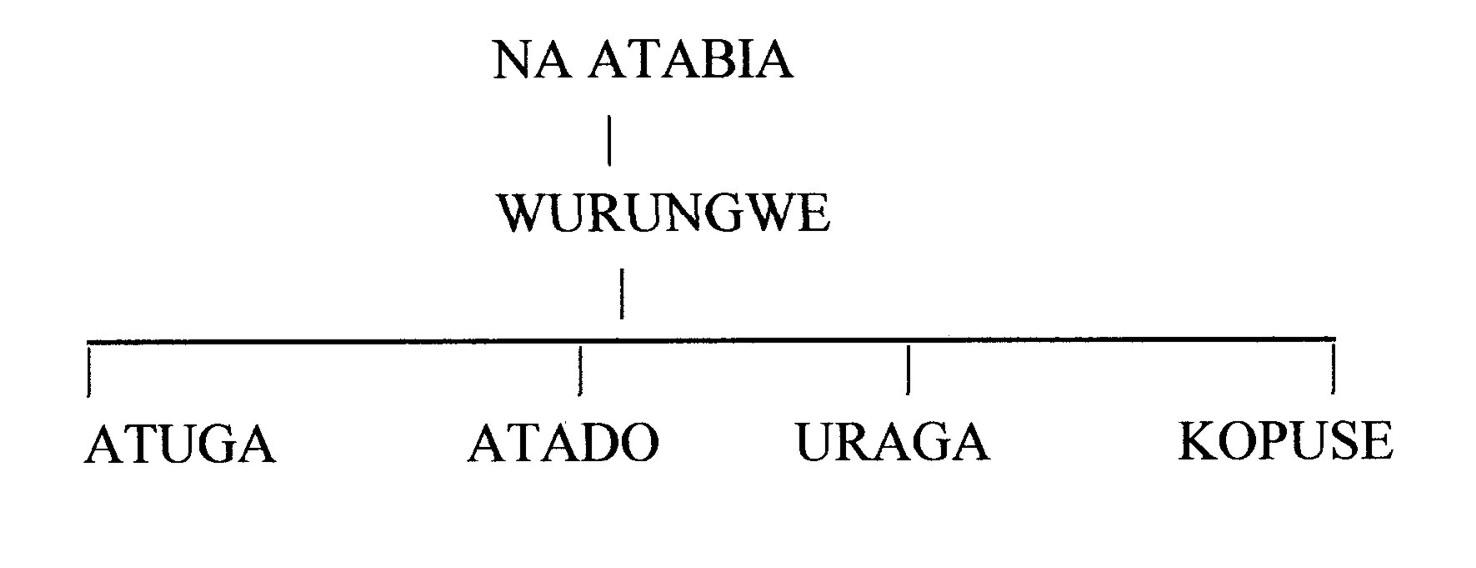

(NAG, Diaries, 17/8/1932, p. 225). To Kunkwa... Talked about their history, etc., and was just getting down to their relations with Passankwia when Pitadina, the ex-chief of Passankwia, appeared on the scene, having come over for the Kunkwa market. His information proved very interesting and [he] told me a long story of their ancestors, mentioning Na Atabia as the father of the man who came here from Mamprussi. This was the 1st time the name of a Na has been mentioned in my investigation...

However I considered myself lucky to knock up against the very man who had made claims to nearly all [of] Builsa Country in 1919, and who was destooled, owing to Captain Armitage (then CCNT [Chief Commissioner of the Northern Territories]) finding that his claims were groundless.

In his typescript (1933:3) Ollivant gives more details about the early Bulsa settlers and their relation to the Mamprusi of Kpasinkpe:

When Na Atabia was Chief of Nalerigu, he had a son called Wurungwe. This man was banished from Nalerigu for mis-conduct and came and settled at what is now Kadem in the Builsa division of the Navrongo district. He had three sons, Atuga, Atado and Uaraga. Atuga’s sons SANDEMA, WIAG, KADEM and SENIEN formed the villages now called after their names. ATADO formed KUNKWA, and UARAGA formed UASSI.

After Wurungwe had been at Kadema a number of years, his wives went to the river near Passankwia for water. They told Wurungwe to come and stay as there were good fish to be caught from the river. This he did and settled at Passankwia, bearing a son Na Kopuse who became Chief of Passankwia.

There is some truth in this story but I am sure that Wurungwe (if such a man existed) cannot have come to Kadema as there is no recollection of his name in any village in the Builsa division. Even the old men at Kunkwa who heard the story told to me, say that Wurungwe is a fetish at Nalerigu and is no ancestor of theirs - not even the name of a man.

I think the true story is that Atuga, Atado, Uaraga, three brothers, sons of some unknown Mamprussi, possibly Wurungwe, settled at the places already mentioned. Atado then moved from Kunkwa to Passankwia and his sons carried on both places...

...the family tree would run as follows:

The first three of Wurungwe’s sons being born at Kadema and the fourth at Passankwia.

Asavie, mentioned above as Atado’s son, appears also in the founding history as told to me in 2011 by Richard, the Regent of Kunkwa. According to him, Asavie, the first leader though not chief of the Kunkwa people, travelled from Nalerigu. He was accompanied by a Mamprusiman from Wulugu, who settled in Kpasinkpe and became chief of that village.

1.6 Version 6 (v6)

After finishing the raw form of this paper, I was sent a typescript of nine pages titled “Sandema Skin and Divisional Skin” (quoted “Sandema Skin”), the product of a group of authors of the Bulsa Traditional Council. Most of the text, written during the lifetime of Chief Azantinlow, concerns the political structure of the traditional state. On the first page, a historical account describes origin myths of some Bulsa villages. The sources of this account are not mentioned, but I surmise that data were not only acquired in interviews but also by making use of publications (perhaps Parsons and Schott 1977).

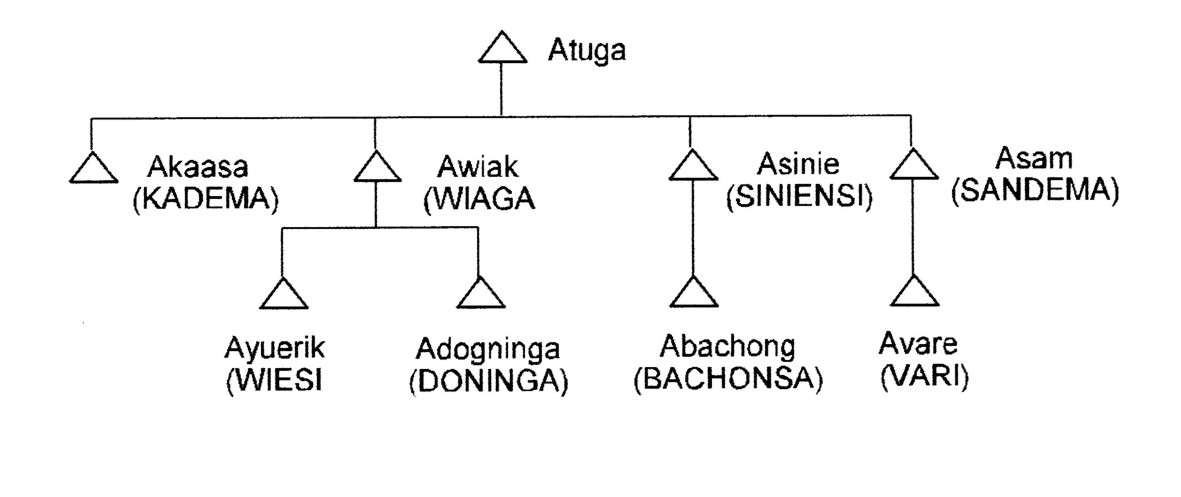

Atuga, the founder of the Builsa nation, left Nalerigu, the capital of the Mamprusi Kingdom, after a quarrel with its chief and wandered to the Builsa country. The migration was motivated by the murder of Atuga’s wife. The Prince who was called Atuga first settled at a place between Wiaga and Sandema where he met the Builsas. He intermarried [with] them and had many issues [descendants]. There were frequent misunderstandings between the children. One of them, Asam, left and settled among some Builsas at Sandema. Akaasa, the eldest son, left for Kadema where he met some Builsa settlers too. Asinie also left and settled at Siniensi where he met some Builsa settlers, and Awiak settled at Wiaga.

1.7 Version 7 (v7)

In the early 1970s, Robert Asekabta from the Sandemnaab’s family, then a teacher at Afoko Middle School (Sandema), handed me the typescript of his drama called “Atuga, the Founder of the Builsa.” Pieces of art are usually allowed a wide range of license and are generally not suited for historical analysis. Nevertheless, I am trying to compare some basic historical facts, as they become evident in the drama, with the other versions of Atuga’s migration and settlement in the Bulsa area. A kind of historical introduction especially suggests R. Asekabta’s knowledge and interpretation of the Atuga myth.

...We believe very much that our great ancestor Atuga was a son of the Nayire Paramount Chief of the Mamprussis. There was a clash between father and son and the son became a banded outlaw who was not to be seen in Nalerigu, the Paramount seat of the Mamprussis. This became the beginning of a big tribe. Atuga then left Nalerigu with his wife to [for] an unknown destination. This later was called Akadem after Atuga's first son. They had four boys and these chaps grew up to be the offspring of four villages. Before then there were already in Southern Builsa, people who are the real Builsas. There was inter-marriage between Atuga's sons and these inheritants [inheritors? indigenous people?]. The four villages are presently called Sandem, Wiaga, Siniensi and Kadema...

1.8 Version 8 (v8)

In A.W. Cardinall’s book on “The Natives of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast” we find a story about the origin of “Sandema, Siniessi, Kadima and Wiaga” (1920: 19) without any mention of Atuga:

A certain son of a Na of Mamprusi, one Wurume, committed adultery with one of his father’s wives. He was banished and came with a few followers to a place called Kassidema in Builsa country. There is no such place to-day, but the site of the former compounds is pointed out. He then set himself up to rule the people... To carry out his intentions appointed his sons to rule over Sandema, Siniessi, Kadima, and Wiaga. He himself grew tired of Kassidema, and after moving to Kunkwa, where he left a son to rule, re-crossed the Volta and settled in Passankwaire...

2. ANALYSIS AND COMPARISON OF THE SEVEN VERSIONS

2.1 Atuga and the Mamprusi dynasty

Most versions agree that Atuga was the son or grandson of a Mamprusi king or at least a member of the royal family. Only in Sandemnaab Azantinlow’s version, the Bulsa as a whole group lived in Nalerigu and had a conflict with the Mamprusi (though not necessarily with the royal family). This version might have played a role in the early years of Azantinlow’s reign when the British regarded the Bulsa as descendants of the Mamprusi and should therefore be subjects of the Nayire (Mamprusi king).

If Atuga was related to the Mamprusi dynasty, it would be worthwhile searching for the name of his royal father and, respectively, grandfather. According to R. Schott (1977: 56) as well as my own research in Sandema-Kalijiisa, Atuga’s father was Akam, and Akam’s father Banyare, but both names cannot be found in the family of the Mamprusi kings and do not appear in one of the seven versions examined here.

The only name of a Mamprusi king that appears in one version about Atuga’s migration is Na Atabia. According to version 5, written by Ollivant (p. 3), Atabia was the father of Wurungwe, Atuga’s father, and both Wurungwe and Atuga left the Mamprusi kingdom in search of new land.

The name Wurungwe appears also in version 8 (Wurume), but none of my Bulsa informants mentioned it. Ollivant doubts if Wurungwe had ever come to Kadema, as his name seems to be unknown there as well as in Kunkwa, and the author is not sure whether somebody of this name has ever lived. The argument that Wurungwe is a fetish in Nalerigu does not refute his being a man, too, since children are often named after a shrine (Ollivant: fetish). Wurungwe plays a great structural role in establishing a tie of the Kadema people to Kpasinkpe, which he approaches quite accidentally when fishing in a river. Perhaps Wurungwe married another wife in Kpasingkpe, for his son Kopuse (ibd.) became chief of that town. This means that a brother of Atuga’s became head of Kpasinkpe and this fact holds true for the historical connections, claims and conflicts between Kpasinkpe and Bulsa villages and chiefs.

Proof in favour of the conjecture that Wurumu had been a living man who was not quite unknown to informants of the 20th century is the note of S.D. Nash (27.5.1919) in the NAG (Accra, Adm 63/5/1,) stating that Wurume was the ancestor of Atuga’s four sons. This information I found on a loose fragment of a page where the name of Atuga is not mentioned:

Wia, Sandema, Senissi and Kalarsi [Kadema?] - This was long previous to the raids of Babatu. The present Chiefs of these villages are descendants .... of the grandson[s?] of WURUME...

Ollivant’s version resembles that of Cardinall (v8) in that it is Wurume (Wurungwe) and not Atuga who had a conflict with this royal father. Ollivant collected his data by field research in Kunkwa and does not mention Cardinall’s book. Cardinall could not copy from Ollivant, who conducted his field research in the 1930s, because his book appeared before in 1920.

Awunchansa, Schott’s informant in Wiaga-Kom (v3), mentions Atuga’s father, whose name was Angurima, and Angurima and Atuga, in his version, were both driven away by the king of Nalerigu to settle in the Bulsa area. Atuga had no children before he married an indigenous Bulsa woman.

2.2 Reasons for Atuga’s exodus

In most versions (v1, v3, v4, v5, v7, v8) the reason for the emigration of a group around Atuga lies in conflicts within the royal family.

It is either Atuga himself or his father who has a quarrel with the Mamprusi king. In versions 2 and 4 there is a conflict over a woman, either between brothers (v4) or between people of different ethnic groups. A quarrel over a married woman is more likely to happen if the two conflicting groups are not related, as it is supposed in version 2, for brothers would regard their brother’s wife as "their" wife who strengthens their family by giving birth to more clan-members.

In version 8 Wurume committed adultery with his father’s wife, a deed which is regarded as the most heinous crime modern Bulsa can imagine. This might be the reason that this incident is not mentioned in any version collected among the Bulsa.

The motif of a pregnant woman whose belly is cut open in order to remove the embryo is, however, so wide-spread in West Africa that we may surmise a subsequent interpolation into the Atuga-story. R. Schott (1990) described and analysed 24 versions of this motif, eight of which he had collected in the Bulsa area (Sandema, Wiaga-Kom, Wiaga-Chiok, Kadema, Kanjaga and Fumbisi).

It is not surprising that the informants from Kom and Kpasingkpe (i.e. from Non-Atugabisa) put the blame for the conflict on Atuga’s father, a man who had “wronged his father" (the Mamprusi king) and been "banished for mis-conduct,” while others blame Atuga’s brothers or make the envy of a Mamprusi group the cause of the conflict and its ensuing fights (v2).

In contrast to the versions 1, 3, 4, 5 and 8, where the conflict takes place within the royal family as an inter- or intra-generational conflict, in Azantinlow’s version it has an inter-tribal character. In the first group, Atuga and his father are of royal blood, which may strengthen their authority among the indigenous Bulsa population, but this also means that their descent creates a certain dependency on the Mamprusi kings, who then might be regarded as the “fathers” of the Bulsa chiefs. Because of the last argument, such versions will find the agreement of Mamprusi chiefs, especially so if they, like the Kpasinkpe chief, had tried to derive a certain overlordship and the right to install Bulsa chiefs from these genealogical ties. These versions, in which the Atugabisa - in contrast to the indigenous population - are somehow dependent on the Mamprusi kings, will also be agreed to by members of the indigenous population, especially if, like Kom, they bear a certain grudge against the Atugabisa.

Chiefs of the Atugabisa, however, and of those Bulsa villages which would not like to live under the overlordship of Mamprusi chiefs, emphasize the non-kinship of Atuga with the Mamprusi.

Myths about the emigration of Mamprusi princes, escaping the overlordship of a king or chief after a quarrel in order to settle in an area far away, have been handed down in the oral traditions of several other villages of this part of Northern Ghana. These villages include Tongo (Tallensi, cf. Fortes 1945 and 1949; and chapter 3 of this paper) and, according to Perrault (1954:61), the villages of Datoko and Tenzugu. According to Lentz (2003:143) the theory that descendants of ruling families emigrated from their home kingdoms, mostly because of conflicts over the succession, is widespread in West African historiography and in many oral traditions.

We also find examples of whole ethnic groups leaving the neighbourhood of their hosting king. In the history of the Koma (Kröger and Baluri 2010: 72-91), a neighbouring group of the Bulsa, Koma clans who had lived near Nalerigu or Gambaga to avoid Babatu’s slave raids, left their hosts to settle in the present Komaland as one tribe.

2.3 Sojourns during the Emigration

The route of Atuga’s migration is not irrelevant because mentioning the name of a town or village may mean that the group stayed there for some time, that alliances, friendship and intermarriage or religious connections were established, or that the reason for leaving that village was another conflict.

As intermediate stations, the following places are mentioned: Naga (v1), Gambaga (v2) and Tongo (v4). The phenomenon of the holes in the Gambaga rock may have been the starting point of finding an explanation for them in history and were thus connected with Atuga’s emigration. In fact, man-made holes in granite rocks, big and small, round and oval shaped, can be found in the whole of Bulsaland and certainly in other parts of Northern Ghana.

The custom of Sandema giving a cow to the Tallensi every year was certainly the consequence of a promise made to the big Tallensi shrine (Tongnaab) and of this promise being fulfilled by the spirits of the shrine. It was not quite out of place to connect this vow with Atuga. It is, however, extraordinary that only Sandema has to give a cow to the Tallensi group that visits the Bulsa area every year. The consequences of fulfilled vows are usually taken over by the eldest son – here it would have been Akadem – or by all sons.

2.4 Farming activities

In none of the seven versions did Atuga’s migratory group invade the Bulsa area as conquerors who, by means of their weapons, brought the indigenous population into a kind of dependency. On the contrary, if they were given a piece of land for agriculture by an indigenous land-owner, they even started a certain kind of dependency. It is, however, more probable that they could take hold of unclaimed pieces of bush land and cultivate them. But even in this case, they would have been obliged to sacrifice to the relevant tanggbain (earth-shrine) and recognize the teng-nyono (priest of the earth), in whose ritual area they had settled as one of their ritual leaders.

Given that Atuga’s farming activities are only mentioned in version 1 and indirectly in version 7 (“scarcity of land”, “agriculture is encouraging”), we may surmise that it was a matter of course for the authors or narrators of the other versions.

Today we find Atuga’s descendants as chiefs in all four villages where Atuga’s sons had settled (Kadema, Sandema, Wiaga, Siniensi), although descendants of the indigenous sections form part of that village. We have no knowledge of when and how they took possession (or created?) the chief’s office. One reason for the peaceful occupation of land can perhaps be found in the following chapter (2.5).

2.5 Intermarriage with indigenous people

Although there might have been women in Atuga’s group, the majority of the group probably consisted of men. Moreover, the unmarried women of the group were certainly relatives and as such were not considered as potential marriage partners. Marrying indigenous people had important consequences: marriage alliances between the two lineages made for a peaceful co-existence. Furthermore, in later centuries there have never been any marriage-prohibitions between the two groups, which means that nowadays probably all Bulsa are descendants of Atuga as well as of the indigenous population. If today some Bulsa feel to be Atugabisa, this refers only to their patrilineal descent.

As regards language, the very small group of immigrants had no chance to force their Mampruli language on the local population, and they probably adopted the local language very quickly.

2.6 Naming his sons

The episode about naming the four sons has a very aetiological character, i.e. a given fact (the names of the four villages) is the starting point for constructing a suitable story that explains how the villages got their names. After this the present facts function as a proof of the authenticity of the story.

In R. Asekabta’s drama (III,1), Atuga’s family is aware of performing the name-giving ceremony, which is different from Mamprusi customs:

ATUGA [to his wife AKPALING]. My dear wife, before long I would say that there should be a great feast whereby our sons could be named.

AKPALING: That should be the case. Back in Nalerigu we would be going against custom if we do this but here we can change the custom to suit us.

The distribution of the parts of the animal does, however, not fit well into Bulsa customs of distributing the meat of a slaughtered animal, be it for a sacrifice or a secular meal.

Today the eldest son often has a claim to one hind leg. The bladder of an animal is not regarded as something very valuable. Before the inundation of Bulsa households with plastic and rubber commodities from Asia, the bladder was often given to small children, who, after blowing it up, used it as a ball. My Bulsa friends and I do not know a Buli word wioh with the meaning ‘thigh’. Perhaps it should be wiok/yuok, meaning ‘hip’.

Also the linguistic derivations of the names from the parts of the animal’s body seem to be doubtful in some cases. The alteration of u - a (sunsum > Sandema) is, to my knowledge, quite uncommon in Buli phonology. Naming children is usually done a few months or years after birth in the segrika ritual. In our story the four sons seem to be of an advanced age.

2.7 Settlements of Atuga’s family

The first place where Atuga settled in the Bulsa area is controversial.

Versions 1, 4, 5, 6 and 7 mention such a settlement, namely in Kadema (v1, v2, v7) or "at a place between Wiaga and Sandema" (v4, v6). Although Azantinlow, the former Sandemnaab, does not mention a place name in Schott’s published account, he is a fervent adherent of the thesis that the first settlement was at Atuga-pusik (personal information), which is today an abandoned settlement near the Sandema Boarding School, i.e. between Wiaga and Sandema.

Cardinall mentions Kassidema as the place of Awurume’s first settlement. “There is no such place to-day, but the site of the former compounds is pointed out” (p. 19). If the abandoned settlement was situated near Kadema, Kassidema might just be another name for Kadema, although Cardinall also uses the name “Kadima”. On the other hand, I never heard Atuga Pusik referred to as “Kassidema”.

At first glance the Kadema hypothesis seems to be more probable, for even today Atuga’s wen-bogluk (shrine), a huge mud-construction near the Wiaga-Kadema road which still receives sacrifices, seems to prove it. But Azantinlow told me that Atuga lived at Atuga-pusik until his death, which was before all four of his sons founded their own compounds at different places. Akadem, as the eldest son, took his father’s wen-stone and built his ancestor shrine in front of his new compound in Kadema.

The existence of Atuga’s grave seems to be a more convincing argument for finding at least the place where Atuga died. But R. Schott (1977: 162) relates:

This [Atuga’s grave], however, was shown to me at two different spots, viz. one near Atuga-pusik, and another one near Kaadema...

That Atuga’s sons settled in Siniensi, Wiaga, Sandema and Kadema is proven by local traditions and the genealogical charts of these villages. Nowadays, when kinship groups leave a compound, they usually settle in the vicinity of their old residence if serious conflicts do not precede their exodus. In versions 1-5 and 7, we do not hear anything about conflicts among Atuga’s sons, but the distances between their first place of settlement and their new ones makes us surmise that they were looking for a distinct spatial separation. My hypothesis of conflicts between Atuga’s sons is confirmed in version 6, when the author writes about “frequent misunderstandings between the [Atuga’s] children.”

Lack of land in the neighbourhood is no convincing explanation because, at that time, land was not scarce. It is, however, possible, that each of the sons was striving for a kind of chieftaincy or at least a kind of leadership over the indigenous population without too much contact with their brothers.

2.8 The indigenous population

It is a matter of fact that Atuga did not come into an uninhabited country, but that there were settlements of an indigenous population all over the area of the present district. When Parsons mentions only the villages of Gbedema, Yiwasi, Bachonsa and Wiesi, this list is certainly not complete. In each of the four villages of the Atugabisa there are lineages which claim to have been in this region before Atuga.

In most of the myths quoted above, the reader gets the impression that these four villages were founded by Atuga’s children. In version 6 it is, however, explicitly mentioned that in Sandema, Kadema and Siniensi, the Atugabisa met “Builsa settlers” when arriving at these villages.

In Asekabta’s drama the indigenous people are called “Southern Builsa,” which is not quite correct because parts of this population are living in nearly all Bulsa villages.

2.9 The chronological integration of Atuga into Mamprusi history

Seen from a chronological point of view, Na Atabia, who, according to Perrault (1954:47), reigned from approximately 1760 to 1775, might well be Atuga’s father or grandfather and, as such, would be the link between the Atugabisa and the royal Mamprusi dynasty. Atabia, the son of the fifth Mamprusi king Nawaali, was the king who left the old residence of Gambaga to settle at Nalerigu, which became the new capital.

If Perrault’s statement of Atuga being the grandson of Na Atabia is perhaps doubted, another chronological clue is provided by the fact that all versions indicate that Atuga and/or his father came from Nalerigu not Gambaga. Thus the founding of the new Mamprusi capital (around 1760?) provides another terminus post quem of Atuga’s emigration.

During Atabia’s reign other royal family members left their father to found new chiefdoms and settlements. According to Perrault (1954: 63), Ali, the founder of Bawku, was Atabia’s son, which means that he was Atuga’s brother or uncle (father’s brother).

The attempt to set Atuga’s migration into the period of early colonialism, when the first whites tried to gain influence in present Northern Ghana, has been refuted in 2.2.

3. ATUGA AND MOSUOR: A CLEAVAGE IN THE SOCIETY?

The most precise and detailed description and analysis of a migration story are provided by M. Fortes in several of his publications on the Tallensi. Even at first glance these texts show a striking similarity with the Atuga myth. Also Mosuor, a member of the royal Mamprusi family, had to flee from his home country after a conflict and he settled in Tongo (Tallensiland). After his death three of his sons founded new villages or joined the inhabitants of older settlements (Yamelog, Sie and Biuk).

Nevertheless, compared with Atuga’s migration, there is an essential difference with regard to the consequences of this migration, especially within the socio-political structure of the present Tallensi society. Fortes describes the relations between the Namoos, the descendants of Mosuor, and the Talis, the original population, as follows:

(1949: 2) ...the Tallensi are internally divided by a major cleavage into two clusters of clans, the Namoo clans on the one hand, and the Talis clans and their congeners on the other. These two groups are distinguished by differences in their myths of origin, their totemic and quasi-totemic usages and beliefs, the politico-ritual privileges and duties connected with the earth cult and the ancestor cult, and to some extent by the their local distribution.

(ibd.: 3) These two groups, we learnt, never combined for defence against or attack on neighbouring ‘tribes’. Indeed, they were the traditional enemies of one another and war sometimes broke out between Namoos and Talis in the Tongo area... The office of chiefship (na’am) is considered to be characteristic of the Namoos, the tendaana-ship of the Talis and their congeners, but neither office is the exclusive prerogative of either group.

The Bulsa are certainly not "internally divided by a major cleavage" into the clans of the Atugabisa and the Non-Atugabisa. Although "the two groups are distinguished by differences in their myths of origin," the religious beliefs and rituals are approximately the same in the whole Bulsa society if we make allowances for smaller differences as they may exist between different villages and clans and even between two families of the same lineage. But there are probably no essential beliefs and rituals that distinguish the Atugabisa as a whole from the other groups.

It is true that in Sandema, Wiaga, Kadema and Siniensi the chiefs claim a direct descent from Atuga, but, to my knowledge, an Atugabiik (Sing.) does not reign over the population of any completely indigenous village.

There are teng-nyam (earth-priests) from the indigenous layer of population with the ritual area of their earth-shrine being inhabited by Atugabisa and Non-Atugabisa, but I know at least one case with the reverse distribution of roles, i.e. the teng-nyono (Sing.) is an Atugabiik and some of the people are indigenous (cf. also 4.2).

In pre-colonial times it happened relatively often that inter-clan conflicts arose which developed into a feud with fierce battles. One of the conflicting parties might belong to the Atugabisa and the other to the autochthonous population, but it was probably just as often that both belonged to only one of the two groups.

After the arrival of the Atugabisa, the number of conflicts between these and small groups of the autochthonous population might have been higher than in later periods when numerous marriage alliances and new kinship ties prevented severe conflicts. R. Schott (1977:160) was told that "the original Bulsa were partly driven out of their homeland by the onslaught of various incoming groups." Wars of the Atugabisa as a whole against other Bulsa groups did not take place.

Although Fortes writes that the two Tallensi clusters (Namoos and Talis) "never combined for defence or attack on neighbouring ‘tribes’," warriors of many Bulsa villages belonging to different clusters fought against the Zabarima and their leader Babatu in the battle of Sandema.

Negating a "major cleavage" within the Bulsa society does not mean that the consciousness of genealogical and historical descent has completely vanished among the living people, but it has not determined their in-group feeling as much as that of the family, lineage/clan, village and tribe.

This consciousness may, however, come to the surface when there are interactions and competitions among Bulsa of different villages. Before the Bulsa District consisted of two constituencies, there were discussions in the political parties about whether their top candidate should be Northern or Southern Bulsa. When, after the election of 1979, a man from Siniensi became MP of the Bulsa constituency, a young Southern Bulsa told me that it would be just for the next MP to be a Southern Bulsa.

Bulsa men and women living and working in bigger towns outside the Bulsa District are generally organized into associations. In Bolgatanga there existed two of these Bulsa groups in the 1970s: one recruited by Southern and the other by Northern Bulsa. Both had their own meetings and festivals, and there was even a certain rivalry between the two. If, however, the interests of all Bulsa in Bolgatanga had to be defended against Non-Bulsa, they co-operated harmoniously.

The division of the Bulsa District into the Bulsa North and Bulsa South constituencies was not a result of pressure or lobbying through the Atugabisa or the others. Rather, the cause of this division was just the political idea that all constituencies should have approximately the same number of voters. When in 2012 the Bulsa District, the then-largest district of the U.E.R., was divided into a Bulsa North and Bulsa South District, this was the decision of the central government in Accra, and I did not hear anything about strong pressure from the Atugabisa or the Southern Bulsa. After the creation of the two districts, there was no exultation among the intellectual Bulsa; some feared that the political unity of the Bulsa was endangered while others were quite sceptical about whether this division would really bring more technical and economic development to the whole Bulsa area.

4. ORIGINAL MYTHS AND HISTORY OF NON-ATUGABISA

It would be too simple to classify all of the Bulsa into two groups consisting of Atuga’s descendants and the indigenous population. The histories of the Bulsa villages which are not direct descendants of Atuga can be classified into three groups: In the stories of informants from Sandema especially, the founders of several of these villages are somehow associated with Atuga; they are either relatives or just companions who came together with Atuga from Nalerigu. Other versions stress an independent emigration from other places, e.g. from the Kasena, Frafra or Tallensi. Lastly, some other groups claim to be indigenous, which is often expressed through the image that their forefather came from heaven.

An exact description of the history of other Bulsa villages surpasses the purpose of this essay and can be studied in R. Schott’s paper "Sources of a History of the Bulsa in Northern Ghana" (1977).

4.1 Bachonsa

According to Azantinlow (Schott 1977:157) and also to the author of “Sandema Skin”, Bachonsa’s founder, ABACHONG, was ASINIE’s son, while other authors (e.g. Parsons in version 1) regard the people of Bachonsa as Non-Atugabisa.

Olivier (NAG, Diaries 19/7/1932) was not very successful in collecting data about Bachonsa’s history: "I was unable to get much news from these people [Bachonsa] but they originally came from Wiaga.”

4.2 Biuk (Biu, Biung)

The original history of Biuk has been described by Fr. Isaac Akapata (2009: 34-35). There seems to be no doubt that the first inhabitants of this place did not come from Mamprusiland. Avobika, the founding ancestor (see 4.7), is said to have lived in a cave north of the present village. The thick forest around his original settlement is still the "realm of the dead" to the Biuk people, i.e. after death their souls wander to this forest called Akugimoniga (west of the Abelnaba river). Avobika’s name, given to him by a man from the neighbouring village of Gani, means "popped up like a mushroom" (Akapata 2009: 34).

While in the original myths of other villages the autochthonous character of the first settlers is expressed by their imaginary descent from heaven, in Biuk their origin is associated with the earth (living in a cave; "popped out of the ground").

Furthermore, according to Cardinall (1920:13) the ancestors of other places called Biung (e.g. in Tallensiland) lived in caverns:

But it is interesting to note that the sections named Biung (a word of forgotten meaning) nearly always lay claim to the fact that they themselves were from the earth and that their ancestors dwelt in holes in the ground.

4.3 Chuchuliga

Schott (1977: 161) and Olivier agree that the people of Chuchuliga originate from Kasena places, but while Schott mentions Chebele (Tiebele) as "the original place from where a man called ACHULOA came and settled in Chuchuliga," Olivier (NAG, Diaries 1932) states that some people of Chuchuliga originated from Chiana and some from Tongo.

In “Sandema Skin” we read about two immigration events:

(1) Abendaa of Bilinsa in Sandema crossed Aninzim [River] into Chuchuliga. There he had several outstanding sons, among them Atie, who founded Tiedema.

(2) ...some immigrants... from Melle in the Upper Volta, among them Achuloa. Achuloa intermarried with them and with time became the ruler of Chuchuliga...

Although the author mentions the immigrants from Sandema first, it is strange that the village received its name from the second group coming from the north.

In 1911 Ataa Akankoba, Chief of Biuk, told me that Achuloa was Avobika’s sister’s son, which means that this sister was one of the Achuloa’s father’s wives. Avobika is still venerated in a big shrine in front of the Biuk chief’s compound.

4.4 Doninga

Also the genealogical ties of Doninga’s founder with Atuga are regarded controversially.

When R. Schott (1977:151-52) visited this village, he was told the following story about its origin by Mr. Anaru from the Dorinsa section:

ADONING was a hunter. He probably came through the land of the Frafra (to the Northeast of Bulsa country). At first he settled in Kandiga, c. 10 miles east of Navrongo). The Kandiga people speak Nankani, but originally they were Bulsa. He left that place on a hunting trip, riding on a wild bush cow. When ADONING reached the present site of Doninga, he met some people there who were Sisala, and these Sisala were performing sacrifices to a boghluk (a shrine, in this case a tang-gbain). ADONING stood by and heard them say a word which is "sila" which in the language of the Sisala means "get up and get it". Then ADONING shot the one who performed the sacrifice and killed him. As soon as the Sisala had realized this they ran away. Then ADONING returned to Kandiga and told his children whom he had begotten there, that they should pack up their things and follow him to a beautiful land (teng nalung) he had discovered. - In other versions of this story I [R.S.] gathered in Doninga, the founder was said to have come from Wiaga or from Kaadema. The motif of the roaming hunter, finding good farm land, is, of course, widespread in West Africa (cf. Cardinall 1931: 97, 232).

In Azantinlow’s account (Schott 1977: 155) as quoted above (4.2), Adognina (Adoning) is Akaasa’s (Akam’s), Awiag’s, Asam’s, and Asinie’s full brother. Like these he left his family and “built [his house] at Doninga” (ibd.).

This version is partly in agreement with a passage of Olivier’s account on the early history of Gbedema (see below, 4.6), according to which the original people of Gbedem "first settled at Doninga where they found the Mamprussi family from Kadema."

According to version 6, Adognina was the second son of Awiag and, as such, a brother of Ayuerik, the founder of Wiesi.

As quoted below (Gbedema 4.5, Schott, p. 161), at a later period descendants of Tallensi moved from Gbedema to Doninga.

In the NAG (Accra) I (F.K.) found only a short note on the origin of Doninga.

25/10/1932: The Doninga people originate from Nalerigu and Wiaga ... They have had no dealings with Mamprusi and had no chiefs before the Whiteman came.

If they really originated from Nalerigu, the capital of the Mamprusi, the assertion that they had no dealings with Mamprusi sounds a little confusing.

4.5 Fumbisi

According to most versions R. Schott collected about the origin of Fumbisi, the founder’s name was Afim/Afin, Afimbiik or Afindem, his father’s name was Akanyanga. I (F.K.) prefer the name Afim because Afimbiik sounds like a singular derivation from Fimbisa. If the person was called Afimbiik, his descendants should be called Afimbiikbisa, which is not very convincing. Afindem sounds like a plural, ‘the people of Afim’ (Sing. of dema is denoa).

In at least three versions, Afim with some followers left Gambaga because of quarrels. The cause of these quarrels might give us some clue about Afim’s original status.

In one version when disputes arose over guinea fowl eggs, this may mean that Afim came from an ordinary farmer’s compound, for royal princes would not quarrel about eggs. This story would go together with a tradition that Afim was a hunter. "As he was hunting, he came and saw this land [here] and it was good, he settled here" (Schott, no date, p. 3). A nobleman or son of a king would not leave his residence only because of a patch of good farmland.

Another cause for leaving Gambaga adopts the common motif of the pregnant woman, whose belly is cut open, in this case to see the sex of the unborn child (cf. also a similar motif in Atuga’s story, p. 2 -1.2. and in R. Schott’s publication of 1990). The ensuing quarrel forces Afim to leave Gambaga.

Other informants claim that Afim and his relatives "quarrelled because of chieftainship" (Schott, n.d.: 3). This cause seems to be the most convincing one to me. The fact that Afim brought sampana-talking-drums from Gambaga to Fumbisi speaks in favour of this version, since only chiefs, and usually important chiefs or kings, are allowed to possess this type of drums. If the Gambaga chief was the Nayire (Mamprusi King), this would mean that Afim left Mamprusiland before Atuga, who emigrated after Nalerigu had been founded and had become the royal residence.

There are again different versions about Afim’s travelling routes from Gambaga (ibd. p. 2), e.g. by way of Bolin, Nyandem (near Kanjaga) and Kanyanga. Schott (ibd. p. 3) writes about the last place:

According to one informant, Afimbiik and his followers "first settled in Kaadema at a place called Kanyanga. They settled near a pond. When they saw that the water was not good for drinking, they left that place.

It is surprising that Afim’s father’s name was Akanyanga (ibd., p.1). If Afim’s father came from Gambaga together with his son, he should have been named there as a child and not, as an adult, after a place which the family, according to the above quotation, had to leave (soon) because of the bad quality of its water.

Akanko, the chief of Fumbisi, told Schott that their forefathers settled at a river called Kanyangsa (Plural of Kanyanga?), which was situated near Wiaga-Kom. (Another informant said that it was between Wiaga/Kadema and Kologu). Today the descendants of the first settlers of Kanyanga believe that after death their souls go from Fumbisi to that place (ibd., p. 9). This phenomenon, like Afim’s father’s name, makes us surmise that Kanyanga settlement was not only a short temporary stay but a real place of origin or at least that the family had stayed there for a longer time. In all likelihood the Kanyanga version had been combined with the Gambaga migration in later times.

Schott’s informants unanimously declared Awuuba "to be the most senior of Afimbiik’s sons" (ibd., p. 4). Awuuba’s shrine is venerated by several of Fumbisi’s sections and he is regarded as the founding ancestor of Fumbisi Yerinsa, a section from which chiefs are still elected today.

In contrast to the versions discussed above, in the account “Sandema Skin and Divisional Skins” Afim came, like the founder of Kanjaga, from Yisiak in Sisalaland, and Baasa and Kasiesa “who migrated from Akag-yer[i] in Sandema” assisted him.

4.6 Gbedema (Gwedema, Bedema, Godema)

The population of Gbedema seems to be descended from different waves of immigrants, but there is no connection to Atuga’s family.

Olivier, DC of Navrongo, gives us an unusually detailed description about Gbedema’s origin.

NAG: 19/8/1932. Gwedema is a place whose ancestors had nothing to do with Mamprussi. They came from Chakani in Kassena country north of Nakon in the Haute Volta. The Chakani people, in their turn, are said to have come from a place called SIA [F.K.: Tallensi area?], whence also came the people who are now at Chiana, Kayoro and Nakon, pure Kassena all.

These original people to go to Gwedema first settled at Doninga where they found the Mamprussi family from Kadema. They did not get on well with these people and after a few years moved to Gwedema. They had married the women there who spoke Buli, the language now universally spoken in the Builsa division, and have kept the language... since.

Also R. Schott was told that the first ancestors came from the Kasena area in the north, but the names he mentions differ from those of the DC’s account.

The people of Gbedema claim that their ancestor came from a place called Wasiga (or Wusiga) in the North. He passed through Chana, where the section called Gwenia is directly related to AGBERO or AGBEDO, the founder of Gbedema (1977:161).

This version resembles very much that of “Sandema Skin”:

The founder of Gbedema migrated from Wasa in what is now called Upper Volta [Burkina Faso]. There were two brothers. While Agbiiro continued to Builsa, Agbiidem stopped at Chana in Akassena territory.

Some Gbedema sections, e.g. the "old Chief’s" lineage, believe that they are derived from the Tallensi (ibd.):

...an ancestor named ATONG (meaning ‘a man from Tong’ in Tale-Land) founded an off-sho[o]t of the great sanctuary of the Tallensi at the "external bogar" near Tengzugu... Some of the Tallensi descendants went from Gbedem to Doninga; others, from Wiaga, formed part of the population of Wiasi (Yuesa) in the South.

In Olivier’s account (see above) a descent from the Tallensi is only indicated indirectly when he says that the people of Chakani (where ancestors of Gbedema originated from) came from Sia, which is possibly the Tallensi village Sii, Siik, Siek, Siega or Shiega.

4.7 Gbedembilisi (Godemblissi, Godembisa)

There seems to be no doubt that the small village of Gbedembilisi ("Small Gbedema") is an offshoot of Gbedema. When my informants of the Gbedembilisa chief’s family asserted that their village had not had chiefs in pre-colonial times, it is possible that for some time after their emigration they still recognized the chief of Gbedema as their political leader. Schott (1977: 161) was informed that

a branch of these people [ancestors of Gbedema] split off and founded Gbedembilisi and Jaadem, another one called Wasik from Gbedem-Kunkoak founded Yiwasa and Wasik-Kunkoak (today called simply Kunkoak or Kunkwa) in the south.

According to “Sandema Skin,” “Agbedembiik, son of Agbiiro [the founder of Gbedema] and his kinsman Anyu settled at Gbedembilisa.”

Quite extraordinary is Cardinall’s version about the origin of Gbedembilisi (1920: 17-18):

In the south-eastern corner of the Navarro District is an area of fairly thick bush... A forgotten number of years ago a hunter passed that way and decided to settle. Without propitiating the spirit of land he could not do so. He therefore went to the nearest tindana, who was living at Buguyinga, some twelve miles away, and by him was appointed tindana of the proposed settlement. Returning to the chosen spot, he built his compound and called the place Gunua. In course of time a family came from the north, and, liking the country, asked the Gunua tindana for land. He pointed out the land called Iassi, but did not appoint a tindana... In course of time more people came, and to-day, forming the community of Godemblissi, recognise a Chief of Builsa blood and a tindana of unknown origin (Kontosi).

This text, interesting as it is, appears to be very enigmatic. The place names Buguyinga, Gunua and Iassi could not be identified and explained definitively. If we assume that these names are Buli, -yinga in Buguyinga may be a variant of yienga, the definite plural of yeri (house, compound), Buguyinga would mean “the houses of Bugu”. Bugu, however, could not be found on a map. The location and the name of Gunua are enigmatic, too. The second syllable of this name might be explained as Buli noa (mouths) or noai (mouth). If the first syllable can be referred to Gbedema (also spelled Godema, dema = people), Cardinall’s story might more easily be associated with the other versions about the origin of Gbedembilisi.

Iassi, mentioned by Cardinall, might well be the Bulsa village of Uassi.

It seems very improbable to me that the tindana (correctly teng-nyono) was a Kontosi (Kantussi). These ethnic groups, most of them being Muslim traders from the present Burkina Faso or the North West of present Ghana, appeared in the Bulsa area at the beginning of the 20th century.

4.8 Kanjaga

While there are usually only a few scattered notes to be discovered about the origins of the villages whose inhabitants do not descend from Atuga, I could find four different accounts on the early history of Kanjaga: R. Schott (1977: 145f), R.S. Rattray (1932: 400-401), S.J. Olivier (NAG, diaries, 23/10/1932) and information collected by Schott in Fumbisi.

Although all four sources maintain that Kanjaga was founded by a man called Akanjag or Akana, there are otherwise very great discrepancies in the presented stories.

In 1975 Schott interviewed 13 elders and studied the manuscripts of Mallam Fuseini, A.S.P. Anab and S.C.A. Seidu in Kanjaga. His collected versions on the early history "differ radically" from Rattray’s story. While all of Schott’s informants said that "Akanjag or his father Akunjong came from ‘Mampuruk,’ i.e. the country of the Mamprusi in the east" and only one said that he came from the sky, Rattray relates that Akana (Akanjag) was a Kasena blacksmith whose grandfather left Kurugu near Dakai (Burkina Faso), moved to Chakani (near Po) and then to the present place of Kanjaga, where he "built a compound on the side of the hill now known as Kanjag Pen (Kanjag’ rock)" (Rattray 1932:400). After some time another group from Konyon, a now abandoned settlement between Wiaga and Kologo, settled at Kanjaga. Many conflicts between the two groups arose, over the course of which Apiu of Konyon, "helped by Finbisi, Gwedema, and Doninga, drove Akana’s descendants away to Genisa (ibd.)." After that incident the leaders of the Konyon group became the chiefs of Kanjaga.

The third source about the early history of Kanjaga, an account by DC Olivier (NAG, Diaries, 23/10/1932, p. 247), is in agreement with Schott’s statement that Akanjag’s father, Akwunjon, came from Mamprusiland, namely from Passankwia (Kpasinkpe). From there he moved to Yuwassi and his son, Akanjag, became the founder of Kanjaga. Like Rattray, Olivier mentions a second group among the early inhabitants of Kanjaga. Their first leader, Akasa, was a Kassena and came from Kurugu (today Burkina Faso). "He came through Isalla [Sisala] country down to Santejan and crossed over to Kanjaga. He is said... to have reached Kanjaga before Akanjag".

If we compare this version with that of Rattray, we might suspect that Rattray’s (or Olivier’s?) informants confused the names of the leaders of the two groups. While the first settlers in both versions come from Kasenaland and the second group from the west (Konyon, Kpasinkpe), Akanjag was the leader of the Kasena group, according to Rattray, and he and his father arrived at Kanjaga from the west according to Olivier and Schott.

Schott collected some notes about the origin of Kanjaga in Fumbisi. The following anecdote (Schott, n.d.) does not only give an explanation of Akanjaga’s name but indicates a certain seniority or superiority of Afim, who helped Akanjag in an extraordinary situation.

It is said that one day Afindem was hunting in the bush on some personal errands when he discovered a man in the hollow baobab tree. This man was asked by Afindem to come out of the hollow tree, but he said that he would not because he did not want his body to be wrinkled. Afindem persuaded him hard and he took him to a place where he, Akanjag, as he was called according to his expression that he did not want his body to wrinkle (Buli: kan = not, jagi = to wrinkle)...[from being exposed to the sunlight], would not wrinkle (Schott, n.d.: 2).

Schott was also told that Akanjag was "said to be one of Afindem’s [Afim’s] sons he left at Gambaga" (ibd.). This last statement does not agree with the story about the hollow tree and is not supported by other sources.

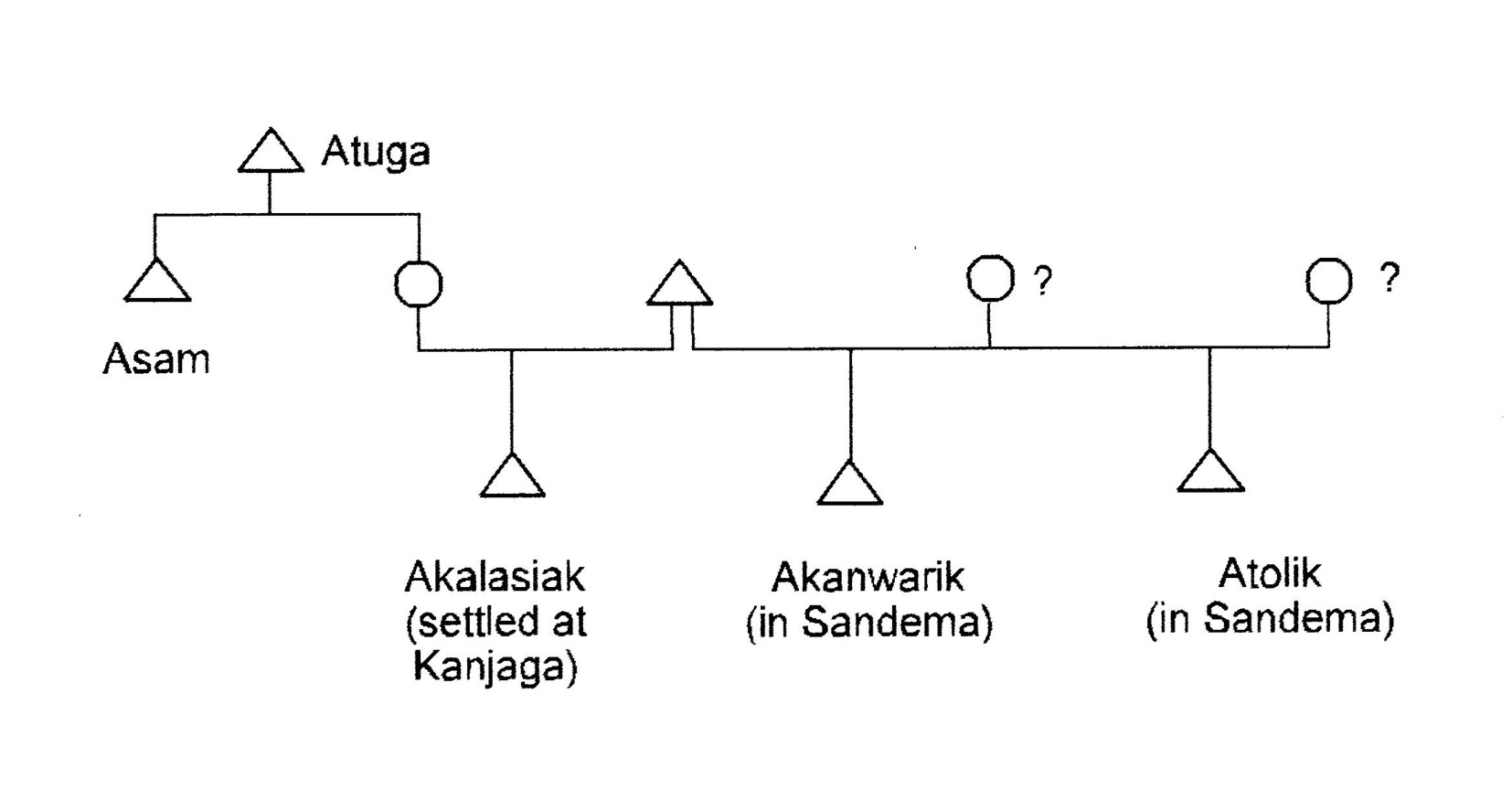

In “Sandema Skin” (p. 1) we find the following passages about Kanjaga:

The origin of Kanjarga is linked up with Sissala (Yisiok). Asam’s sister’s rival’s [co-wife’s] son, Akalasiak, left Yisiok with his parental [paternal?] brother[s] Akanwarik and Atolik for Builsa. Leaving his brothers to join Sandema, Akalasiak went and settled at Kanjarga.

This last version, tracing Kanjarga’s origin to the Sisala people, does not agree with most of the others. Only Olivier (NAG, Diaries 23/10/1932, p. 247) recounts that Akasa’s [= Akalasiak’s?] group, on their way from Kurugu, “came down through Isalla [Sisala] country down to Santejan and crossed over to Kanjaga.”

4.9 Kategra

According to Schott (1977:161) "Afim... founded Fumbisi whence at a later date the people of Kategra branched off."

In the early 1920s many people of Kategra moved to Jadema. On April 20th, 1925, Anilig, with the approval of the Ag. Commissioner of the Northern Province, was elected and appointed chief of the Kategra people in Jadema, where he also took up his residence. The village of Kategra [with the remaining population?] became one of Jadema’s sections. In September of 1933 "the Katigri [Kategra] people moved back to Katigri with the exception of Jankansa who said there is not land at Katigri" (NAG.).

4.10 Kunkwa

Mr. Richard, the present regent of Kunkwa, told me in January of 2011 that Asavie was the leader of the first Kunkwa immigrants from Nalerigu and that he did not come together with Atuga. Asavie had no chiefly title. He came in the company of a Mamprusi from Wulugu, who settled in the present Kpasinkpe and became chief of this village. When he was called back by the Mamprusi king, he drove a peg (kpasiri > Kpasinkpe) into the ground and said that he would always stay here. It is not quite clear whether this myth of origin should indicate a certain dependence of Kunkwa on Kpasinkpe.

Many sources, like Olivier (NAG, Diaries, 18/10/32), stress the close connections between Kunkwa and Kpasinkpe.

...I had already got Kunkwa’s history and as I knew they were of Mamprusi origin and made land sacrifices to the fetish at Passankwa, I asked them whether they now would like to follow Passankwia and so the Na of Mamprussi or whether they would like (being now Bulsa) to come into the future Builsa Tribal Council. They pleaded (?) for Passankwia to a man!

According to Ollivant (typescript 1933:3),

Atado [the founder of Kunkwa], had two sons, Asavie, whose descendants are the Tindanas [earth priests], and Kamalo. The latter decided to go to Nalerigu to be proclaimed Chief of Kunkwa. He was stopped by Na Kopuse at Passankwia who told him not to go to Nalerigu, that he would proclaim him Chief on payment of cattle. This Kamalo agreed to and the system [that Kpasinkwe installed chiefs?] was carried on in Kunkwa...

Ollivant’s and Richard’s versions, at first glance quite different, are not wholly incompatible. Asavie, "who was not a real chief" (Richard), might have used his power and influence as an earth priest (Buli teng-nyono) to become a leader or "big man" before his brother Kamalo was made chief of Kunkwa.

Ollivant (ibd.), who also tries to reconcile different versions, offers his own interpretation:

I think the true story is that Atuga, Atado, Uaraga, three brothers, sons of some unknown Mamprussi, possibly Wurungwe, settled at the places already mentioned. Atado then moved from Kunkwa to Passankwia and his sons carried on both places...

4.11 Tandem

Tandem, consisting of the four sections (or villages) of Kpalinsa, Tankansa, Zamsa and Zuedema, is situated between Kadema and Wiaga. It had belonged to the former and is now part of the latter. In political elections it was part of the Bulsa South constituency.

In Azantinlow’s account (Schott 1977: 155) a connection of the founders of Tandem and Doninga and Atuga is established:

ATUGA’s children are: AKAASA; AWIAGH, ASAM, ASINIE, and he also begot ATAM and ADOGNINA. All of them were from one mother... ATAM also went and built [his house] in the middle between Kaadema and Wiaga; that [place] is called Tandem.

Schott’s informant Awunchansa from Wiaga-Kom states that the people of Tandem lived in the Bulsa area before Atuga’s arrival and that they were indigenous ("came from heaven"):

(Schott 1977: 157) ...The people ATUGA met were the Kom at Komdem [kom dem, people of Kom]. They were Bulsa. Chamdem [cham, shea tree, and dema people] (=Tandem) settled near a shea-tree and that is why they are named after that tree... Chandem and Kom came from heaven. If they come from anywhere else, I don’t know it. They came down from heaven with their wives and children and after they had some children, there was some intermarriage between them. AKOMA and ACHANDEM are the founders (ngaasa) of the Bulsa. AKOMA (or AKOMAO) was the leader (kpagi, elder)...

It is questionable whether Tandem, as concerns the descent of its population, can be treated as a unit. In 1981 I tried to research the early history of Tandem-Zamsa. Agbandem, my Zamsa-informant, told me that Anaanateng, their founding ancestor, had lived here before Atuga came and that he is not only the forefather of Zamsa, but also of several other lineages in other Bulsa villages, e.g. in Wiaga, Sandema, Gbedema and Kanjaga. To my knowledge this is the only web of kinship relations for people whose first ancestors lived before Atuga came to Bulsaland.

Nevertheless, my Zamsa informants tried to establish kinship ties between Anaanateng and Atuga. The latter was allegedly the grandson of Anaanateng’s father Ataduok. My informants could not tell me whether Ataduok immigrated from the Mamprusiland or whether Atuga was - in their genealogical system - the son of indigenous people, which means that all migratory myths about Atuga have to be discarded completely. For my part I believe that the fictive genealogical ties to Atuga were added at a later point of time, for there are too many elements of ancestor veneration that seem to be very ancient and differ from those of the other Bulsa.

The ancestral shrines at the abandoned settlement of Anaanateng’s family do not have their equals.

...they consist of big, irregular stones, most of which reminded me of European border stones... Of the oldest male ancestor-bogluta only Atengdaara’s [Anaanateng’s son] stone is visible, the lower half of which is buried in the ground. Immediately under this stone his father’s (Anaanateng’s) wen-stone is said to lie, and under this Ataduok’s stone, the oldest known male ancestor of this lineage and perhaps of the whole Bulsa area.

(Kröger 1982: 17-18)

Besides, Anaanateng and his wife are also venerated in the form of two terracotta heads, as they are found in the Koma area. It is, however, probable that these heads had been found in recent times and had been ascribed to the first ancestors.

4.12 Vare / Vari

Regarding the origin of Vare, I found a short note in Schott’s paper (1977: 160):

The original Bulsa were partly driven out of their homeland by the onslaught of various incoming groups. In the traditions it is said that some fled to Kologu, some went to Naga, others to Vaari...

Moreover, Olivier could not collect solid data in Vare when he passed this village (NAG, Diaries, 15/7/1932):

...I asked the people of Vare whether it was a fact that the Mamprussi had first settled there when they came here [?], but they said they had never heard so.

According to “Sandema Skin,” (p. 1), “one of Asam’s children Avare left and resettled at Vare.”

4.13 Wiesi

Like people of other villages the inhabitants of Wiesi (Yuesi) are indirectly made relatives of Atuga. Ayuerik, the founder of Wiesi, was, according to Azantinlow (Schott 1977: 157), a son of AWIAGH. Olivier, DC of Navrongo District, was given a piece of similar information in Wiaga, whereas people in Wiesi told him "that their ancestors came from Nalerigu, that Atong was their first father and Wiassi was the name of his son and he formed the present village" (NAG Diaries, 22/10/1932).

4.14 YIWASI / UWASI

About the founder of this Bulsa village, I could find only two short notes which, however, coincide to a large degree. According to Schott (1977:161) “Wasik from Gbedem-Kunkoak founded Yiwasa” while the author of “Sandema Skin” mentions only that Ayiwaarik departed [from Gbedema] and settled at Yiwaasa. The name given to this village seems to be associated with Waasa, Agbiiro’s original living place, in present Burkina Faso.

Our examination of the early history of Bulsa villages has been difficult and time consuming. The many different versions of one historical event make it especially hard to decide what really happened centuries ago.

There is not doubt that Atuga, together with a small group of Mamprusi, came to a land that was inhabited by indigenous and Buli-speaking Bulsa and that further immigrations from neighbouring tribes completed the structure of the present Bulsa society. It is surprising that a considerable number of the people who are generally regarded as autochthonous are (later?) associated with the Mamprusi immigrants through (fictional?) genealogical ties. In most cases it is the Atugabisa who construct these alleged ties. However, in a few cases the indigenous people (e.g. in Zamsa) also find consanguineous or affinal relationships with Atuga’s family.

Although among the present Bulsa there is a consciousness of belonging either to the Atugabisa or the Non-Atugabisa or "Southern Bulsa," this has not lead to a cleavage within the Bulsa society.

Among all the other ethnic groups of Northern Ghana, the Bulsa are in the extraordinarily favourable condition of having no larger groups of foreigners among their population. The Kantusi (Yarisa) have been assimilated to a great degree and the nomadic Fulani, living outside the Bulsa villages, form a very small minority. Associated with this ethnic unity under a paramount chief who is respected by all Bulsa, a community life developed not with greater intra- or inter-ethnic conflicts but rather with a common history throughout the last 150 years and a self-confidence acquired in the successful wars against Babatu.

REFERENCES

Akapata, Isaac, Fr. (2009): Biuk, a Village with Bulsa Traditions. Buluk. Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society 5: 34-41.

Cardinall, A.W. (1920, reprint 1969): The Natives of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast. Their Customs, Religion and Folklore. New York: Negro Universities Press.

Fortes, Meyer (1945): The Dynamics of Clanship among the Tallensi. London, New York and Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Fortes, Meyer (1949): The Web of Kinship among the Tallensi. London: Oxford University Press.

Kröger, Franz (1982): Ancestor Worship among the Bulsa of Northern Ghana. Religious, Social and Economic Aspects. Hohenschäftlarn bei München: Klaus Renner Verlag.

Kröger, Franz and Ben Baluri Saibu (2010): First Notes on Koma Culture. Life in a Remote Area of Northern Ghana. Münster: Lit Verlag.

Lentz, Carola (1998): Die Konstruktion von Ethnizität. Eine politische Geschichte Nord-West Ghanas 1870-1990. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

Lentz, Carola (2003): Stateless Societies or Chiefdoms: A Debate among Dagara Intellectuals. In: Franz Kröger/ Barbara Meier (eds.): Ghana’s North. Research on Culture, Religion, and Politics of Societies in Transition. Frankfurt am Main et al.: Peter Lang.

Ollivant, District Commissioner (1933): A Short History of Buli, Nankani and Kassena speaking People in the Navrongo area of the Mamprusi District (typescript).

Parsons, D. St. John (1958): Legends of Northern Ghana. London: Longmans.

Perrault, P. (1954): History of the Tribes of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast. Navrongo: St. John Bosco's Press,.

Rattray, R.S. (1932, reprinted 1969): The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland. 2 vol., London: Oxford University Press.

Schott, Rüdiger (1977): Sources for a History of the Bulsa in Northern Ghana, Paideuma 23, 141-168.

Schott, Rüdiger (n.d.): Oral History and the Regulation of Social Life in a West African Village: The Example of Fumbisi in Northern Ghana. Provisional Draft. 10 pages (typescript).

Schott, Rüdiger (1990), "La femme enceinte éventrée" - Variabilité et contexte socio-culturel d'un type de conte ouest-africain. D'un conte... à l'autre, La variabilité dans la litterature orale. Paris: Editions du CNRS, 327-338.