Franz Kröger

Two Early Plays on Bulsa History

The history of Atuga’s immigration into the indigenous Bulsa community and episodes of the Babatu's slave raids are among the most vivid events in the collective imagination of the Bulsa. It is precisely these two events that received in-depth treatment in the first pieces of dramatic literature written by educated Bulsa.

Leander Amoak: The Raid of the Bulsa by Babatu

Sometime in the early 1970s, Mr. Leander Amoak, then a teacher at the Sandema Middle Boarding School (now Junior Secondary School) wrote a puppet play on the topic of the slave raider Babatu and, together with his pupils, he made the necessary puppets: Babatu, the Sandemnaab and other Bulsa chiefs and elders, a white man and others. I do not know when or how often the pupils performed the play. In 1973, I was given only a demonstration of it and Mr. Danlardy Amoak— Leander’s son and a teacher like his father— gave me a copy of the manuscript.

The drama, which consisted of four scenes, began with the election of Chief Babatu by his elders. In this scene, Babatu is not described as the leader of a gang of robbers but as someone who is loved and respected by his people and who is called upon (or perhaps requested) to adopt the qualities of Samory: braveness, loyalty, courage, wisdom, etc. Of course, the script is not correct in referring to Samory as Babatu’s predecessor as chief of the Zambarima. Samory was a member of the Malinke tribe and some historians believe that he never actually set foot in what is modern Ghana, although his sons and officers fought several violent battles, for instance against the Gonja.

In scenes 2 and 3, Babatu and his soldiers defeat the inhabitants of Bachonsa, Doninga, Kanjaga and Wiaga, whose surviving warriors flee to Sandema to increase the army of the Sandemnaab (Anaankum).

In the final scene, Babatu is beaten by the joint forces of the Europeans and Sandema, at which point he is taken prisoner and exiled to Yendi. These events again require some corrections. Although it is true that Babatu was defeated in battle at a place south of Sandema (near the Boarding School), this was managed by the warriors of Anaankum and with the help of other Bulsa villages; Babatu, however, was not taken prisoner but in fact fled to Yendi, a town of the German colony of Togo, where he found himself beyond the sphere of British power.

Leander’s play was certainly enjoyed very much by the players and the audience, especially when Bulsa songs were sung by the players (even by the Zambarima!) and sometimes by the audience, as well.

I do not know what happened to the puppets. They would have been worth preserving, either in a safe place at Sandema Junior Secondary School or in the newly founded Bulsa archive.

Robert Asekabta: Atuga, the Founder of Bulsa

|

|

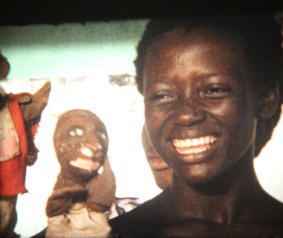

Robert Asekabta in 2012 |

In 1973, Robert Asekabta (Sandema), then a young teacher at Afoko Middle School, handed me a manuscript of a short drama about Atuga. I took photos of the ten pages with my not-yet-digital camera, which resulted in barely readable text. As Robert subsequently lost the original, this is now the only copy in existence.

The play, which consists of three acts, begins at the court of the Mamprusi king in Nalerigu. The Naayire, or king, and his elders are worried about a man called Nabayuri who wanted to see the country submit to British rule. What grieves the king even more is that his son, Atuga, has joined Nabayuri. This anachronistic version must have struck the spectator because, according to tradition, Atuga lived about 300 years ago while what is now Northern Ghana became a British protectorate only around 1900. It is surprising, too, that Atuga, the hero of the play, makes some arguments in favour of submission to the colonialists:

(I,2, p. 4) [You] know very well that our state will be reduced to nothing if we do not associate ourselves with others ...

In the first act, Atuga is presented as a furious warrior who is ready to wage war:

(I,2, p. 4) Atuga (with red eyes shooting like a wounded lion begins to speak harshly...): ... blood would I shed immediately if any dog talks to me...

Atuga (kicking the elder while saying): You foolish old man! I shall tear you to pieces if you are not careful...

The final result of this heated discussion is that Atuga has to leave his country within four days.

In Act II, spectators see a quite different Atuga. The wild and war-thirsty rebel has become a loving husband and sympathetic father. The playwright follows Parsons when he has Atuga settle at Kadema; the episode in which Atuga names his four sons after the parts of a sacrifice is also in accordance with Parsons. The exodus of the three younger sons occurs without another generational conflict; it is instead the scarcity of land that leads them to leave Kadema.

To form the historical basis of his drama, Robert Asekabta collected material in the Bulsa area, made use of Parsons’ booklet and even conducted interviews in Nalerigu. The sober, historical facts were imbued with life according to the playwright’s interpretation. They display outbreaks of anger and hatred but also the tender emotions experienced by a loving married couple.

Note: Robert Asekabta's informants in Sandema: 1. Mr. Apen Abaatuk, a retired nursing administrator (Secretary at National Level), from Wiaga; 2. Robert's elementary school teachers like the late Mr Akangutiba Asuemi Gilbert, Mr. Abu Gariba etc. 3. Robert's parents, especially his father; 4. Legends of Northern Ghana, by St.-John Parsons.