Franz Kröger

Means of Transport in Colonial Times and Today (with special Reference to Ghana)

There are a number of historical reports concerning the first Europeans to have penetrated into the Northern Territories after the colonial powers had established their presence on the Gold Coast nearly 500 years prior. Diaries from the period tell us about colonial officers visiting the outskirts of their Districts and missionaries establishing stations outside of the bigger towns. Little has been written, however, about how these Europeans reached these places. We often imagine explorers and officers riding on horseback but, in my opinion, the utility of the horse has been overestimated in this context.

There are of course alternative means of transport, each with its unique advantages or disadvantages, as the following account will show.

1) Walking

It seems odd to imagine Whites walking on lonely paths to explore a part of the

tropical world heretofore unknown to them. Some of the known “walkers” (or marchers)

were forced to give up their original means of transport—e.g., after their horse(s) had been

killed—and only very few had planned to undertake the entire journey on foot.

Mungo Park (1771–1806), for example, began his first journey (1795) on horseback but, especially

on his return voyage, he was forced to walk long distances.

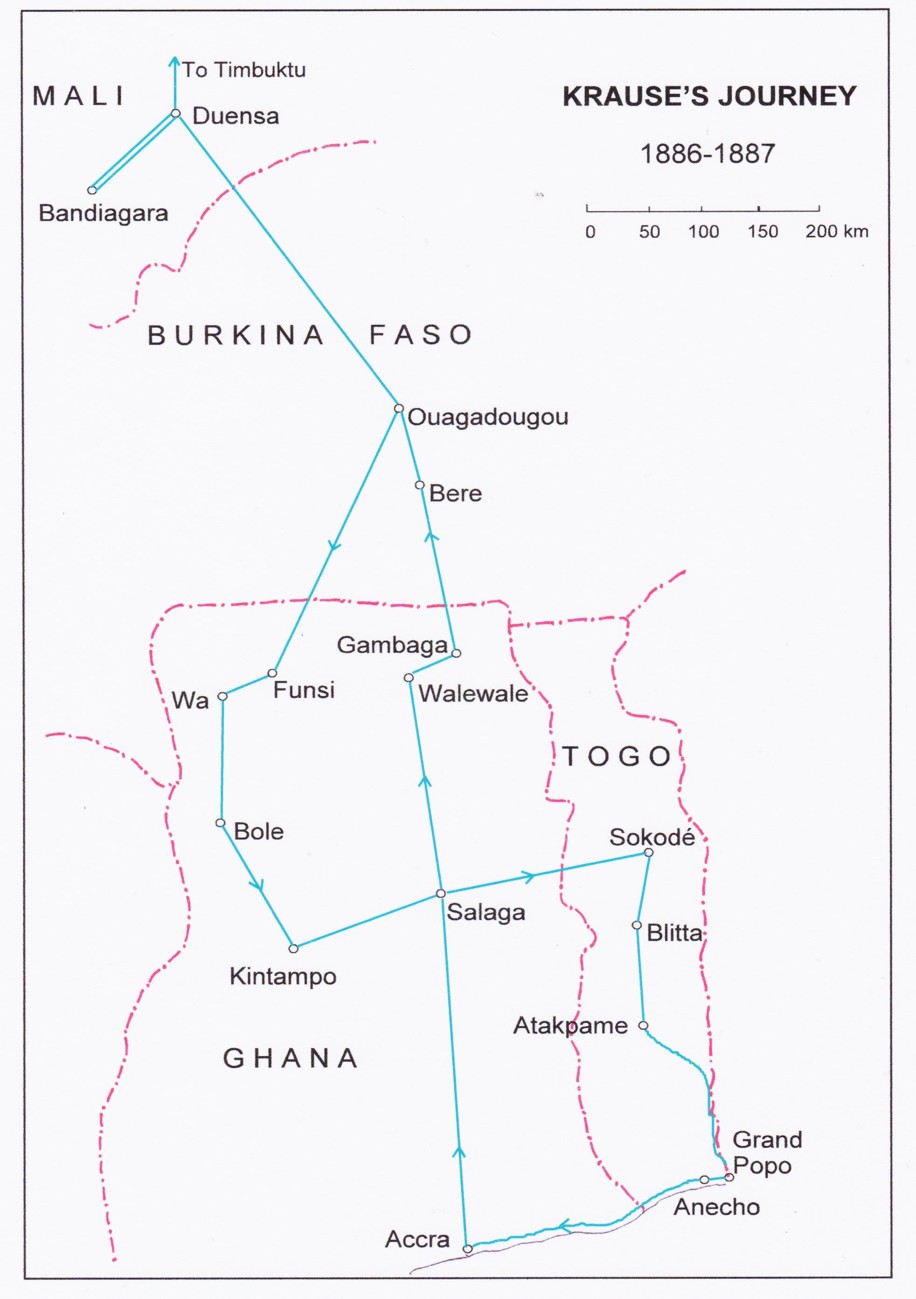

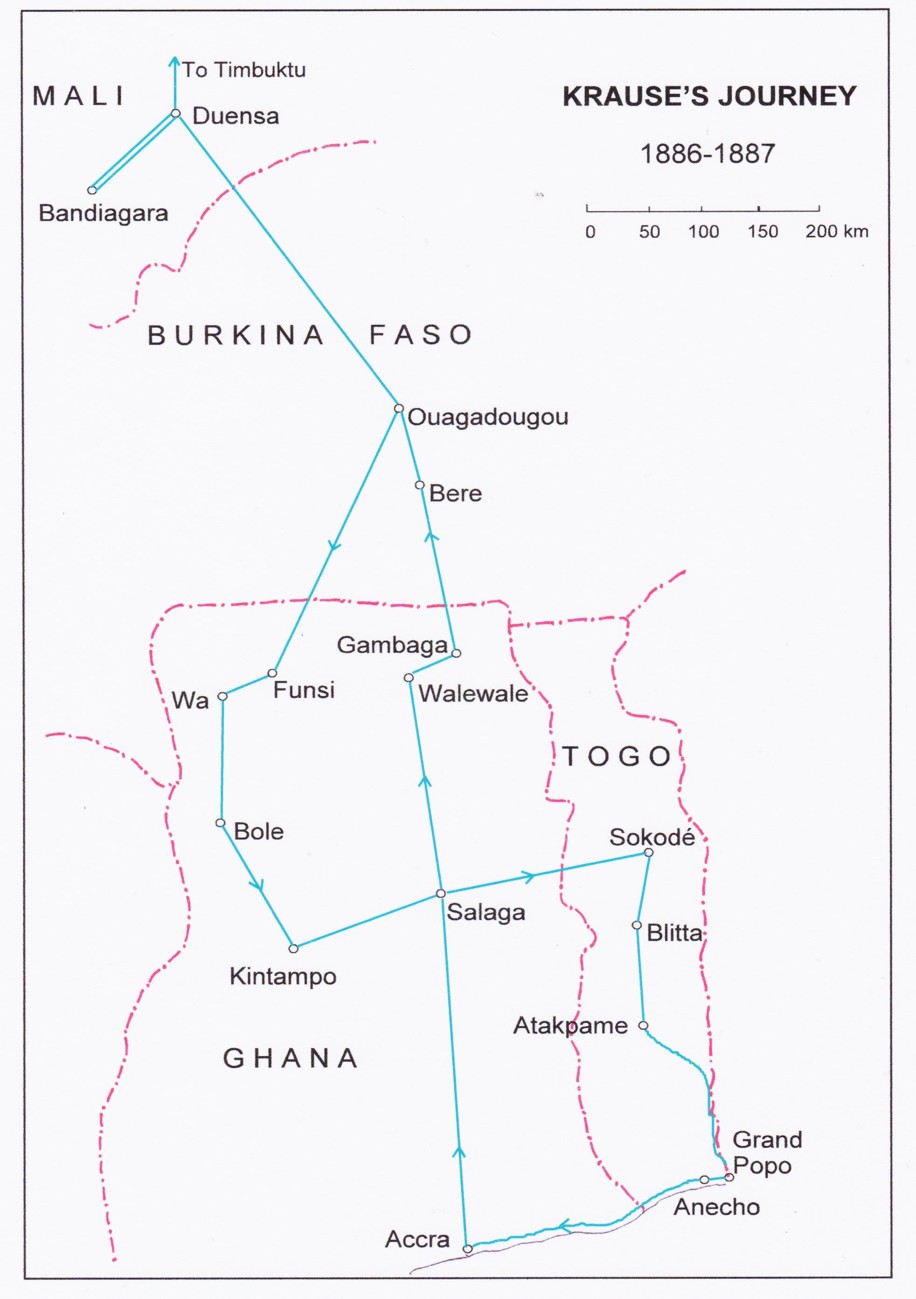

The German linguist and explorer Gottlob Krause (1850–1938), who is not well known in either Europe or Ghana, was not very much respected in his lifetime and has nearly been forgotten by present-day scholars, had serious problems funding his journeys and was widely mistrusted by official European authorities. One reason for this mistrust and hardship might have been his stridently anti-colonial attitude and his refusal to pave the way for any military expeditions that aimed to seize land by entering into treaties with indigenous chiefs.

Following a boat trip from Accra to Kete Krachi in May1886, Krause began his journey to Timbuktu on foot, with capital of 5£ 11s 8d, which at that time corresponded to approximately 100 Reichsmark (expeditions organised by other travellers typically had access to capital of anywhere between 60,000–80,000 Reichsmark). He had no weapons and no servant. Only on long marches did he hire an African to carry part of his luggage, which on his return voyage consisted of plants, seeds, stones, minerals, ethnographic objects, etc. At the end of his travels, setting aside three separate boat trips, he had covered 4,000–5,000 km on foot.

Throughout his journey he never described any serious health problems and only 13 minor attacks of fever. Although he was in possession of quinine, he stopped using it after a “Grunchi” gave him a local plant-based medicine that proved very effective in fighting the fever.

Eager to reach Timbuktu, Krause crossed Gonjaland in only seven days and Dagombaland in five. After being the first European to visit the town of Ouagadougou, he reached Duensa and then Bandiagara, in modern Mali. The ruler of the Masina kingdom, who resided in Bandiagara, did not allow Krause to enter Timbuktu. On his way back, he visited many towns (e.g., Wa) and villages in Northern Ghana that had never before been visited by Europeans. In Beleta (perhaps modern Blitta, in Togo), after having been taken prisoner, he was able to escape only by leaving behind much of his luggage, including a large collection of ethnographic and botanical specimens. During the final stage of his journey he walked, alone and carrying some 15 kg of luggage, from Beleta to Accra, which he reached again in September 1887.

Once back in Germany, Krause was able to sell a report of his journey to a journal (Kreuzzeitung) but the big museums were not interested either in what remained of his collection or in his ethnographic notes, which were destroyed as rubbish following his death.

Krause had recognized that many of the languages spoken in what is now Northern Ghana and Burkina Faso belonged to a single language family, which he named the Gur-languages on the basis that “gur” appeared in many names, such as Gurensi, Gurma, etc. This term is still used by modern linguists even though few of them know it was coined by Krause.

Apart from Krause, only one other person is known to have likely toured Ghana on foot—namely, Cecil H. Armitage, the Chief of Commissioner of the Northern Territories. This is based on an abstract of an address he delivered before the Royal Colonial Institute on June 10, 1913, in which he consistently used the word “march” to describe his movements from town to town. Apart from not having visited Ouagadougou, his route through the Northern Territories corresponded nearly exactly with the route that was later followed by Princess Marie Louise (see below).

2) Carried in Hammocks

Although we find a number of pictures in colonial literature showing a white man in a hammock being carried by two or more Africans, there was little data and few photos that attested to this method of transport having been used in the Northern Territories. One reason for the lack of sources might be that British officers who used this means of transport might have been ashamed to admit to it because being carried might be associated with physical weakness. In the Gold Coast Diaries, the hammock as a means of transport is mentioned less frequently than are walking, cycling and riding; it was likely used primarily for the sick and convalescing.

A.R. Holliday, then the Acting District Commissioner, however, admitted in a diary entry made on 20 November 1918: “...Left Bole [for Kintampo] at 9:25. Started to foot it, but had to give it up and get hammock men, as I find that very little exertion knocks me out...”

If a group had to cross a river, the white officer was often carried on the shoulders of a strong African servant.

3) Bicycles

It would seem that few of the great African explorations were

accomplished with the help of bicycles. Cycling through the virgin forest would have been impossible and

cycling through the savannah would have brought with it a number of dangers.

bicycles. Cycling through the virgin forest would have been impossible and

cycling through the savannah would have brought with it a number of dangers.

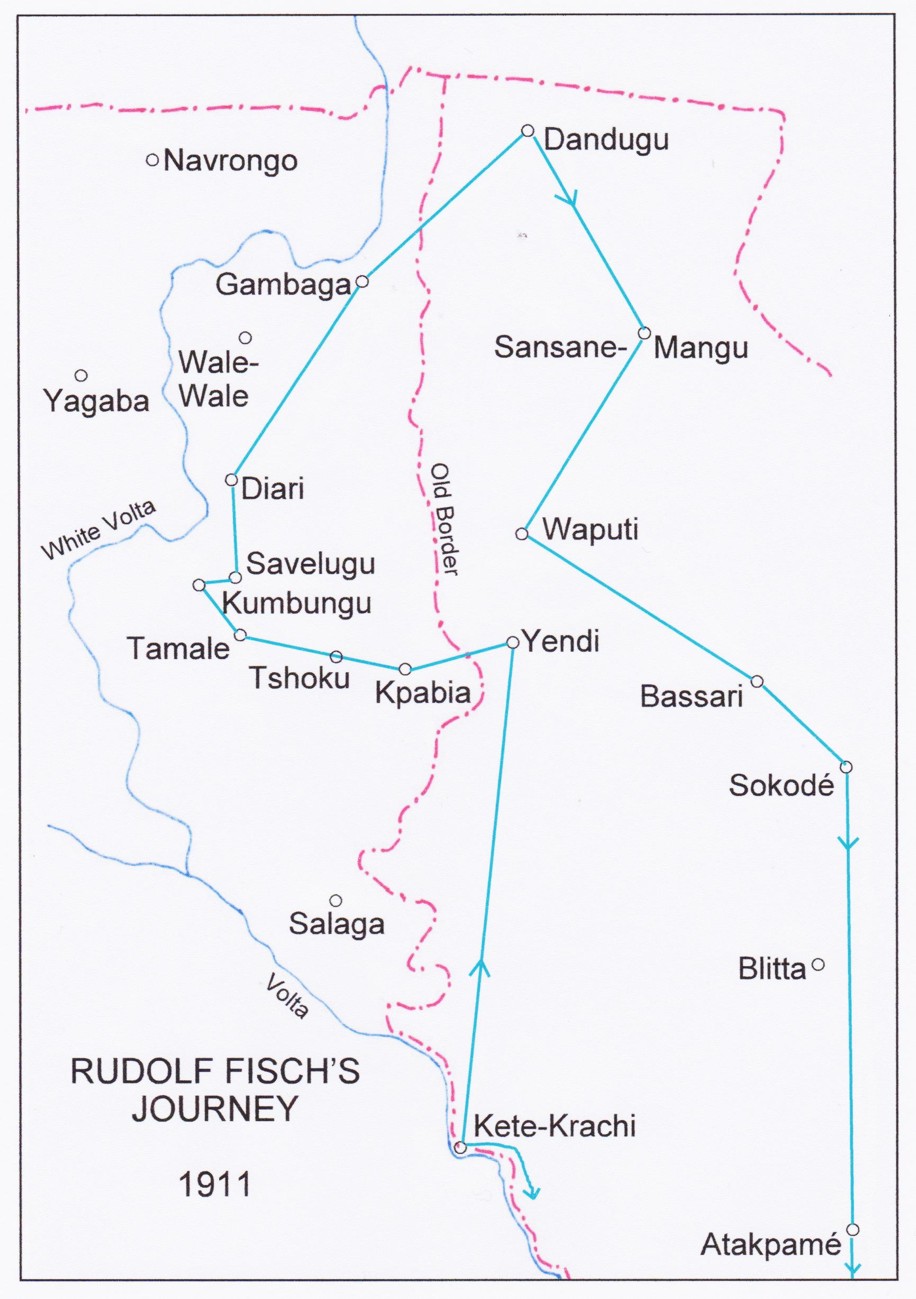

Rudolf Fisch (1856-1946), a Swiss missionary and doctor, together with two friends, did venture to take just such a bicycle trip from the south of Togo into the territories of the Nanumba and Dagomba in 1911. In search of a suitable locale in which to establish a mission station, they visited towns and villages such as Bimbila, Yendi, Gambaga and Savelugu, among others, in the British and German colonies and their hinterlands. Fisch’s book, Nord-Togo und seine westliche Nachbarschaft (Northern Togo and its western neighbourhood; 1911), relates the fact that only the three white people associated with the expedition used the bicycle; the carriers, of course, had to walk.

One disadvantage of the bicycle was that the cycling group had to wait for the carriers to arrive at the next sleeping place. Cycling from Tshoku to Tamale, a journey of approximately 45 km, took the main group just one day, while the carriers needed two. Moreover, the damage sustained by one of the bicycles (e.g., p. 40: a loose pedal) could cause the delay of the entire group. Fisch also complained about the windy bush-paths, which were often obstructed by shrubs and branches. On the whole, however, Fisch’s experiment proved to be successful. Wikipedia even notes that, in 1892, Fisch introduced the bicycle into “the country” (either the Gold Coast or Togo).

More important perhaps were Fisch’s efforts at improving the hygiene conditions and founding the first hospital in Ghana, in the town of Aburi, where he worked as a surgeon (Wikipedia).

In the “Gold Coast Diaries”, bicycles are mentioned nearly as often as are walking and motor-cars as the chosen means of transport for British officers.

4) Cars

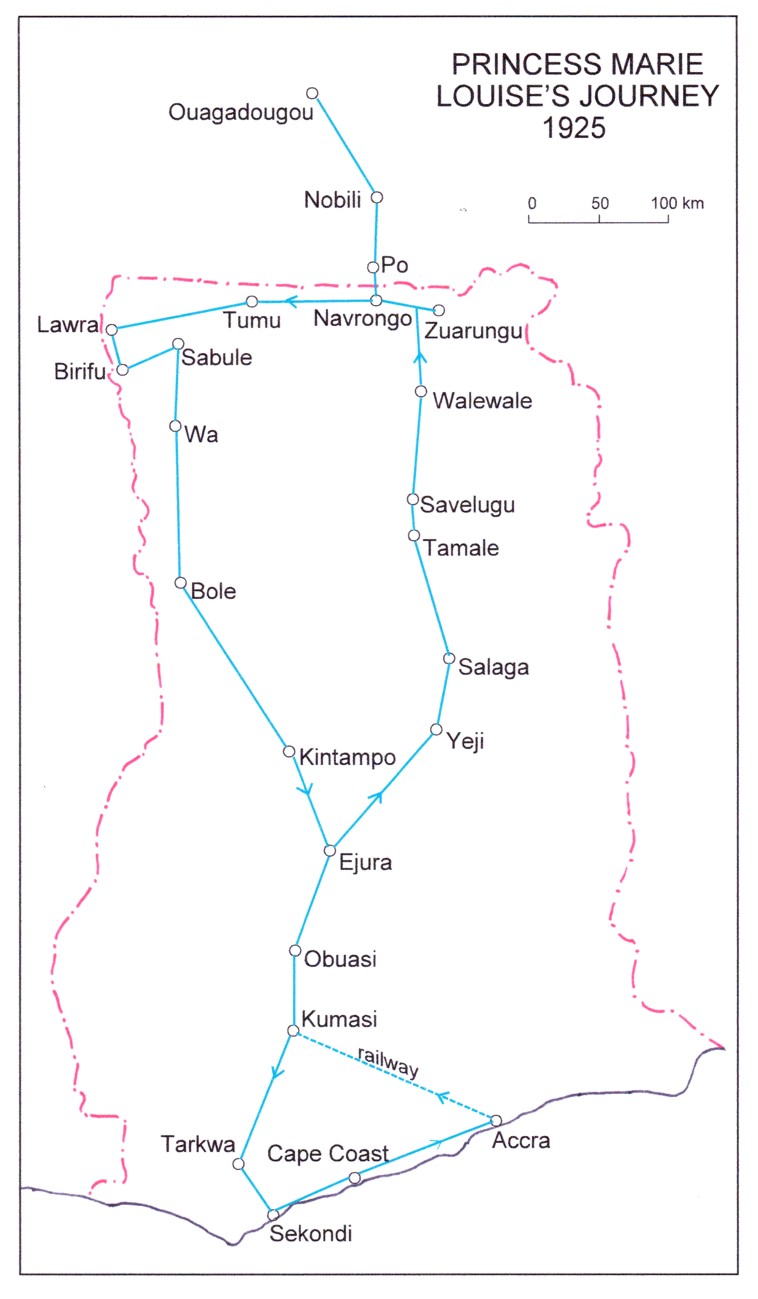

H.H. Princess Marie Louise, granddaughter of the British Queen Victoria, is an early example

of the use of cars and lorries to make a round trip through the Gold Coast and the Northern

Territories. Her excursion (1925) was probably the most luxurious undertaken during the colonial

period. Accompanied by a number of servants, orderlies, cooks, motor drivers, washmen, a

doctor and the Governor of the Gold Coast, Gordon Guggisberg, she travelled first by train

from Accra to Kumasi - with a whole coach serving as her saloon and another for her

personal luggage. In Kumasi, the luggage had to be loaded onto 16 lorries while she and her

entourage travelled in 6 passenger cars. What did she take along on her journey, packed onto

the lorries? Furniture, presents, a bath tub, even horses - the princess enjoyed a ride every

morning before breakfast. The purpose of her journey is unclear. One strong motive was

certainly the princess’s desire to do something extraordinary. Her political activities were

restricted to making contact with chiefs and colonial officers, to the unveiling of memorials,

the laying of foundation stones and to creating personal ties between the native population

and the British crown.

H.H. Princess Marie Louise, granddaughter of the British Queen Victoria, is an early example

of the use of cars and lorries to make a round trip through the Gold Coast and the Northern

Territories. Her excursion (1925) was probably the most luxurious undertaken during the colonial

period. Accompanied by a number of servants, orderlies, cooks, motor drivers, washmen, a

doctor and the Governor of the Gold Coast, Gordon Guggisberg, she travelled first by train

from Accra to Kumasi - with a whole coach serving as her saloon and another for her

personal luggage. In Kumasi, the luggage had to be loaded onto 16 lorries while she and her

entourage travelled in 6 passenger cars. What did she take along on her journey, packed onto

the lorries? Furniture, presents, a bath tub, even horses - the princess enjoyed a ride every

morning before breakfast. The purpose of her journey is unclear. One strong motive was

certainly the princess’s desire to do something extraordinary. Her political activities were

restricted to making contact with chiefs and colonial officers, to the unveiling of memorials,

the laying of foundation stones and to creating personal ties between the native population

and the British crown.

The route of the convoy was not very different from that followed by the other travellers who had visited the North before her (e.g., Armitage 1911): from Kumasi they travelled via Yeji and Tamale to Navrongo, from where they undertook a side-trip to Ouagadougou to strengthen the relationship between the British and French colonial officers. Like other travellers who had passed through the territories before her, she did not pass through the Bulsa area but instead followed the northern route that went via Tumu, Lawra and Wa back to Kumasi.

Princess Louise was regarded by her contemporaries as an emancipated lady who did not shrink from the opportunity to experience an adventure.

5) The Author’s Means of Transport in Ghana

In 1972, when I was first planning a two-year stay in Ghana to work as a lecturer at Cape Coast University, it was a matter of course that I would need a car—especially so as I had planned several excursions to visit the Bulsa in Northern Ghana. When I tried to sell my old car, a Volkswagen Beetle, in Germany, the dealers were only prepared to offer me about 100 German Marks (50 Euro). Therefore I decided to replace the old engine and I had the car shipped to Ghana. I was not very happy with it, as it needed many repairs (which fortunately were quite cheap in Ghana): water would pour through the sliding roof and every time I boarded the ferry at Yeji, my exhaust pipe would scrape the ramp, so it had to be repaired. It was difficult to get petrol in the Bulsa area and travelling off the tracks was troublesome. As I prepared to leave Ghana in 1974, I asked an official institute in Tamale to examine the car for any hidden problems and to estimate its value; I was surprised to hear not only that they appraised it at the high price of 2,000 Cedis (approximately 2,000 present-day Euros) but also that they were willing to buy the car.

On my next stay, which was planned to last three months in 1978, I used a motor-bike, a Suzuki 80. Although it was certainly easier to free the motor-bike from the wet mud than it had been to free a car, and although it was nice to be able to push the motor-bike along if the road became too rough to ride, in the evenings following such tours I was always completely exhausted. I also had one accident when I failed to see a deep hole in the road and could not evade it because of an oncoming car.

Before each of my subsequent stays in Buluk between 1979 and 1997, I would purchase a mobilette in Ouagdaougou. It was well suited for travelling shorter distances but I dared not use it for a trip to, for instance, Bolgatanga or Tamale. I also always had trouble finding the correct mixture of oil (one milk-tin) and petrol (one gallon) that would provide sufficient lubrication while at the same time not damaging the spark plugs.

At last I satisfied my wishes of using a bicycle for transport during the trips I made between 2001 and 2011. I still think it is the best means of transport for covering distances of up to 30 km, a common distance I had to travel daily as part of my anthropological fieldwork. Also, for my stays in Yikpabongo (Komaland), where no petrol was available, the bicycle proved to be the ideal vehicle.

By the way - I was never carried in a hammock!