Carrying the ma-bage from one compound to another

Franz Kröger

Matrilineal Structures in the Traditional Bulsa Society

Anyone who has lived for a longer time in the Akan area of Southern Ghana has certainly noticed that the family structures there are different from those in Bulsaland and most other parts of northern Ghana. At least in previous times, an Akan man or woman regarded his/her mother's oldest brother as his/her father in social, jural and political respects, which means that this “uncle” had to pay for his niece’s or nephew’s living costs, school-fees, bridewealth, etc. After the “uncle’s” death, the (eldest) nephew inherited the “uncle’s” wealth and assumed his social position and rank. Family goods were handed down only through one’s mother, i.e. matrilineally.

Great parts of Northern Ghana follow the patrilineal system, although some ethnic groups, especially in Ghana’s northwest, possess strong matrilineal traditions. The Bulsa are definitely a patrilineal society. That is, a man inherits goods (e.g. land and cattle) as well as offices from his father’s line, e.g. from the father’s eldest classificatory brother (The very complicated patrilineal system of inheritance and succession has been described elsewhere. Cf. Kröger 1982 and Kröger/Meier 2003). Nevertheless, there are also a few matrilineal or uterine structures in Bulsa society.

1) Marriage prohibitions

Every Bulsa knows that he is not allowed to marry a hitherto unmarried woman from certain sections, lineages or compounds. The reasons for such a prohibition may be manifold: The members may belong to the same patrilineage or there are specific ritual ties between the two lineages which forbid intermarriage. From lineages which are regarded as enemies (dachaasa), only wives can be married, which of course would deepen the hostile relations between the two groups.

There is no doubt that Bulsa are neither permitted to marry from their mother’s or mother’s mother’s (Mo Mo) lineage, nor from the mother’s mother’s mother’s (Mo Mo Mo) family. However, in a patrilocal society, the degree of relationship and the residence of the descendants of the last mentioned ancestress are often no longer known to young marriageable people. If elders find out about any blood-relation to a matrilineal ancestress, they usually advise against a marriage.

The rituals of the ma-bage and the juik may serve, among other things, to revive the knowledge about matrilineal kinship and intensify the relations between the two families.

2) Ma-bage rituals

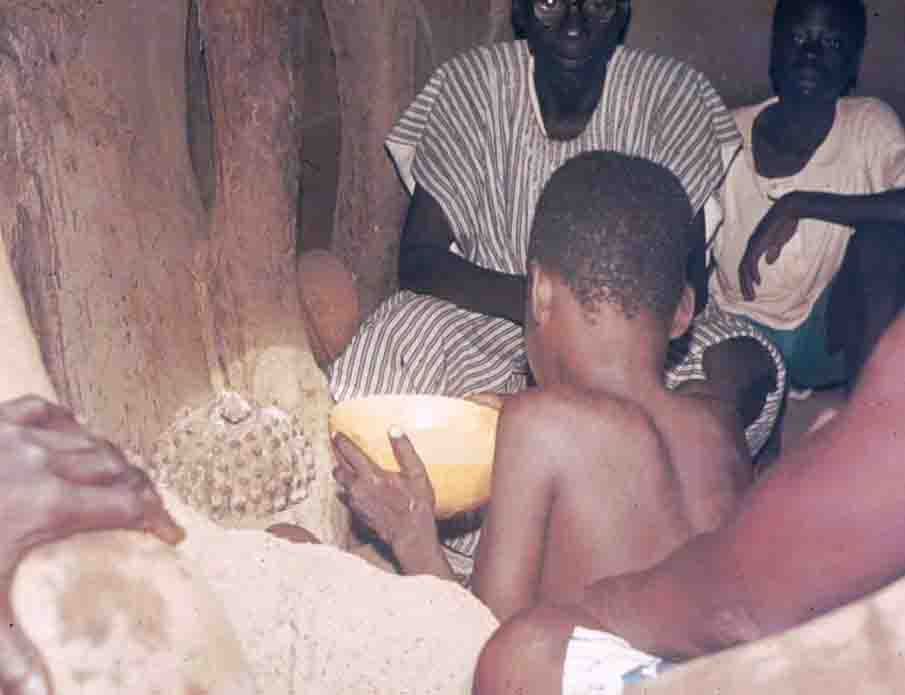

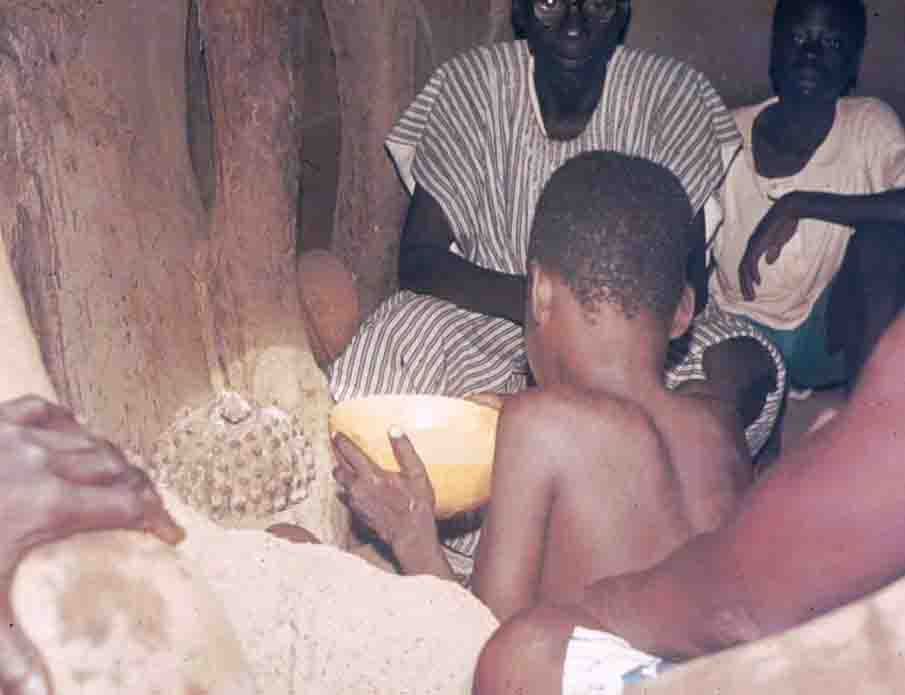

The inter-lineage transfer of a ma-bage in the form of a knobbed ceramic vessel filled with earth

from the usually now abandoned settlement (guuk), where the ancestress

had lived, is one of the old Bulsa rituals with a strong esoteric character and associated with many taboos.

The vessel is associated with the ancestress’s wen, a revered divine power.

The reason for this ritual is the desire to worship a certain matrilineal ancestress in one’s own

compound. Usually the head of a compound initiates the transfer of the mother’s mother of his

late father from the ancestress’s parental compound to his own. I could not discover why the

particular mixture of a patri- and matrilineal ancestry (Fa Mo Mo) is a precondition for

collecting the ma-bage.

The shrine will receive sacrifices whenever the other shrines of the compound are sacrificed to (e.g. before the first sowing or harvesting). The earth of the ma-bage plays a great role in witch ordeals, in which all of the suspected persons must drink a solution of this clay and water.

|

|

|

|

| A knobbed vessel is filled with earth from the guuk |

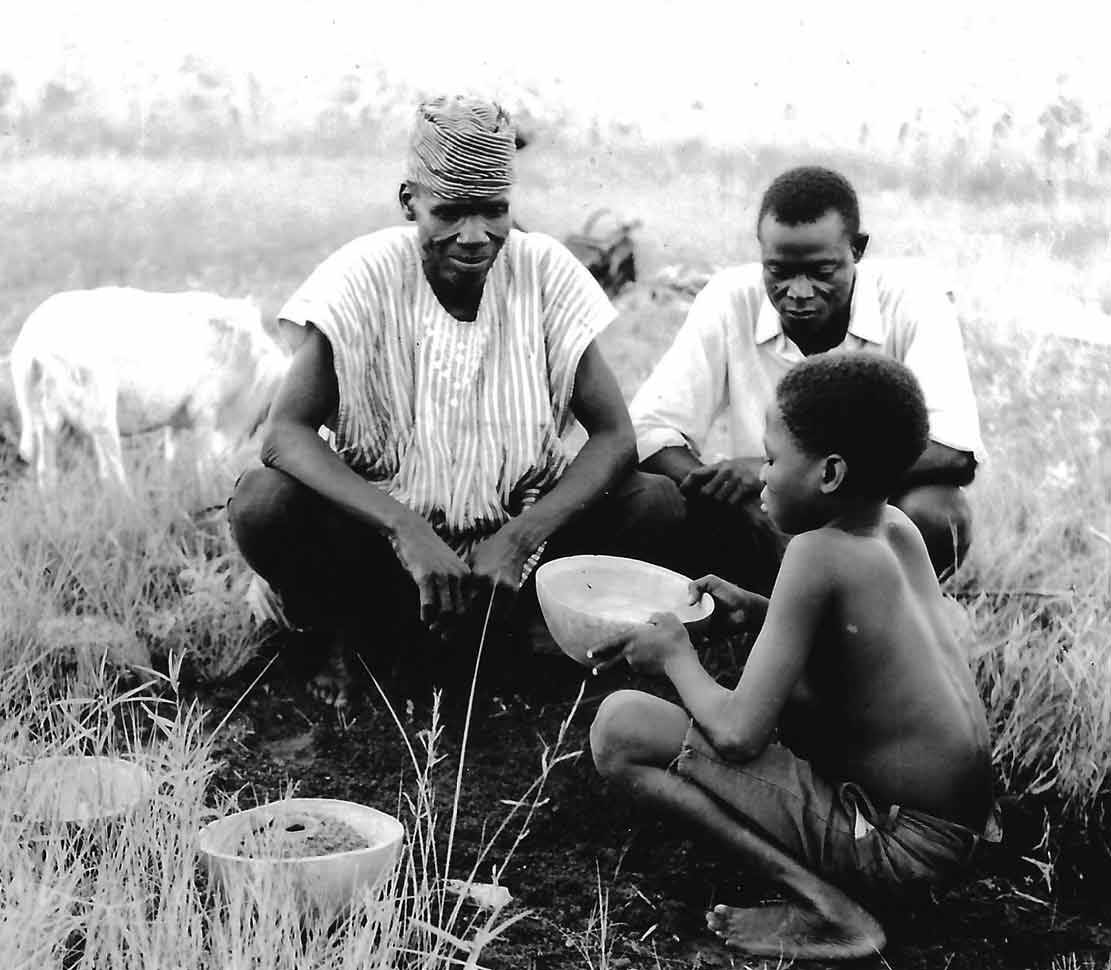

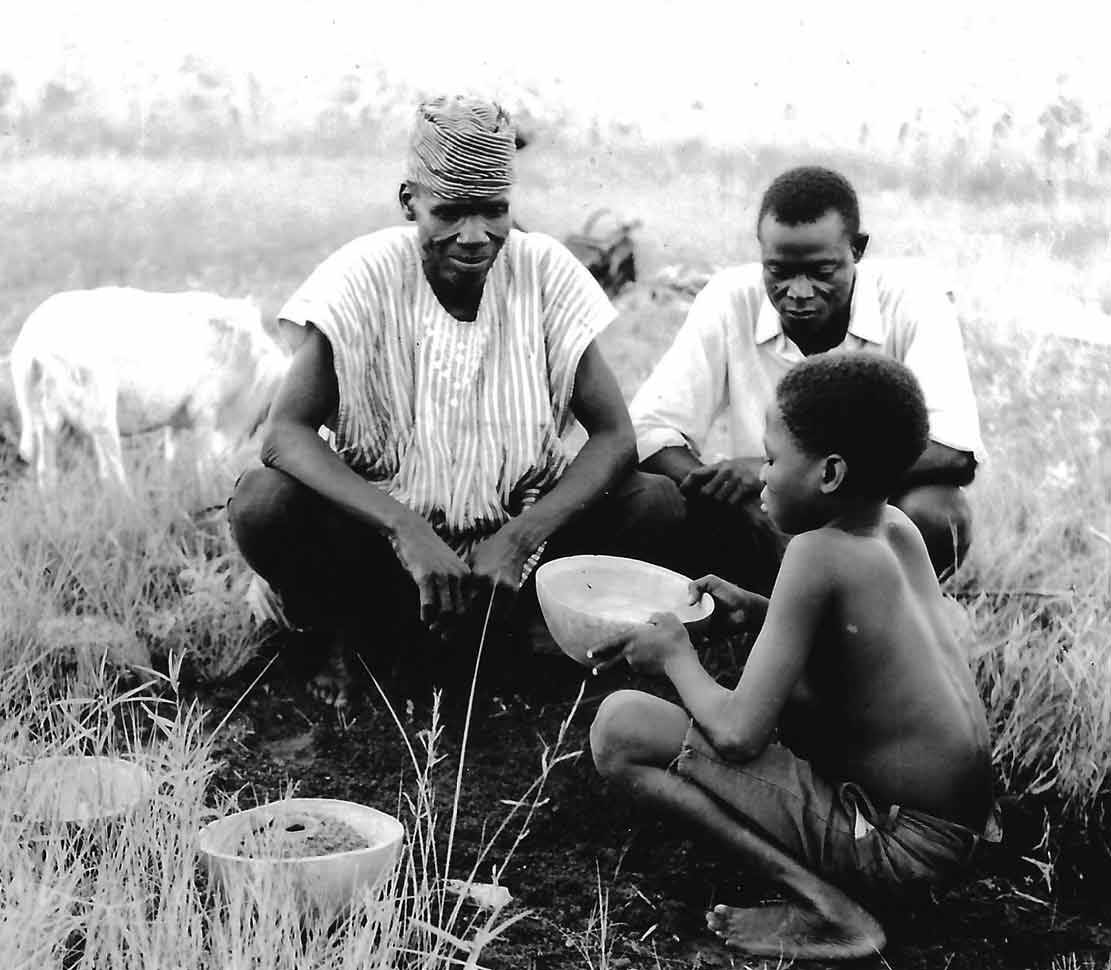

Carrying the ma-bage from one compound to another |

Ma-bage receiving a sacrifice | Three ma-baga in the ancestors's room (kpilima dok or dalong) |

3) Licentious behaviour of the “nephew” (toa biik, lit. sister’s son, or ngesing)

Although usually all sons live in their father’s compound among people of their patrilineage, a particular relationship to their mother’s brother (whom in an Akan society they would call “father”) stresses matrilineality (uterine descent). On his frequent visits to his uncle, the nephew is always welcome.

What Fortes (1969: 30) wrote about the Tallensi may also apply to the Bulsa:

Though he [the nephew] has no property, succession, or inheritance rights in his uncle’s home, a man has special material privileges there, which give expression to the notion of quasi-filial status.

Among the Bulsa, this peculiar relationship is stressed by the nephew being allowed to behave toward his uncle as he would never have dared behave toward his father. Even if he snatches one of his uncle’s chickens and takes it home, he cannot be blamed or punished, because this is an institutionalized act. Similar patterns of behaviour are practised by the Nankanse, Sisala, Mossi, Nuna and Kasena. Many cases are known wherein young Bulsa, having had some conflicts in their parental compound or having not felt comfortable there, left it for good in order to live in their mother’s brother’s compound.

4) Nephews as visitors to a wena-seka

In July 1979 Mr. Leander Amoak (Wiaga-Sinyansa-Badomsa) invited me to take part in a wena-seka ritual when three of his ancestral shrines (Ayarik, Agbana and Adaachoruk) had to be rebuilt in front of his compound. He explained to me that he had to invite “all the nephews of the house” who would come and sacrifice a chicken to the new shrine. I only understood the meaning of “all the nephews of the house” when we started to make a list and include all of them in a genealogical diagram. These invitations included kinship groups whose own patrilineage was related with Ayarik’s male descendants through a woman (Kröger 1982: 40). Apart from matrilineal descendants of the three ancestors whose shrines were rebuilt, younger ancestors and living persons and relatives of the Badomsa patrilineage also appeared (See genealogical diagram, Kröger 1982: 40). For some of Ayarik’s “nephews”, i.e. descendants of his sister, the exact genealogical ties are no longer known today. Nephews from 13 different villages and sections from all over the Bulsaland appeared to sacrifice their chickens.

5) Matrilineality in juik rituals

The mungo species Herpestes sanguineus (Dwarf Mongoose; Buli juik) is a rapacious animal that is feared as both a chicken thief and as a creature causing evil to humans. Nevertheless, an individual mungo may be venerated as a divine being by a single human person (cf. Kröger 2013). Although some specific elements of this cult also appear in other ethnic groups of Northern Ghana, a mungo cult proper exists only among the Koma and Bulsa.

|

|

Juik-skin in a room (dok) |

If a diviner finds out that his client needs a juik shrine, he advises him to visit his mother’s compound and then perform certain sacrifices in his mother’s mother’s (MoMo) compound. This is done not only to inform his matrilineal relatives, but somehow the sacred juik is equated to the sacrificer’s mother’s mother and may

even be called ma (mother). Its shrine, consisting of two stones at the footpath to the mother’s and mother’s mother’s compounds, resembles the shrine of a male person’s mother.

The juik-ancestress is also represented by the skin of a mungo, stuffed with herbs and other magical substances, but it is not offered any sacrifices. Like all old Bulsa women, it is wearing pink-coloured waist-strings and is kept in the sacrificer’s sleeping room.

A strong resemblance between the juik- and ma-bage-rites is evident: In both cults, the mother’s mother is venerated in a shrine consisting of two stones at a footpath, which must be collected from the mother’s mother’s compound after a visit to the mother’s compound, and both shrines are not only venerated but also feared.

6) Witchcraft

Meyer Fortes states the following about witchcraft and matrilineality (1969: 32): "The potentiality of being a witch is hereditary in the female line. A woman’s son and daughter may both become witches if she is a witch". Furthermore, the Bulsa believe that witchcraft is something evil that intrudes into their patrilineage through a wife. Although witches may be male or female, the majority of them are women.

Among some Bulsa informants, there are doubts as to whether witchcraft is really inherited or whether it is transferred to a woman’s children by way of her breast milk. They can cite evidence in favour of their hypothesis by stating that co-wives help each other in bringing up the children of their common husband, but no co-wife would allow another wife to breastfeed her baby.

7) Function and meaning of matrilineal structures

Negative Aspects

For the Bulsa, a woman who married into the compound is a stranger who does not belong to her

patrilineal environment. Although men of the compound, especially the wife’s brothers-in-law,

may be very kind to her and call her "our wife", she will remain a stranger to them. Discussions

of internal affairs of the patrilineage, of ritual decisions and episodes from the family history

take place without wives. These women usually participate in sacrifices only if they themselves

or their children are affected.

As far as matrilineal ancestresses are concerned, this reluctance may even be connected with a

certain anxiety. An old informant from Sandema-Kalijiisa was willing to give me detailed

genealogical data about his patrilineal ancestors, but when I asked him a question about his ma-bage ancestresses, he denied my request by saying, "When I tell you about them, I will not be

able to sleep peacefully at night."

To an even greater extent, this fear is displayed in the juik rites. During the construction of a new

juik shrine (juik-ferika), my Christian assistant refused to give me his services, children of the

compound were driven into the courtyards and even the landlord (yeri nyono) observed the

sacrificial rites only from a distance of about 30 metres. As an explanation for this behaviour, he

later told me that the matrilineal ancestors of his son, who received a juik shrine here, were

strangers to him.

Positive Aspects

On the question regarding which person had loved him most, cared for him most affectionately and who could be relied upon in every situation of his life, most Bulsa men would say the name of a woman with whom he is “only” matrilineally related – namely his mother. Furthermore, his mother’s relatives, whose residence is often many miles away from his, will rank as people of high estimation and affection in his life.

For men who occupy a high position in their patrilineal segment, the relation to their “nephews” (i.e. matrilineal relatives, as it was described in the wena-seka ritual) is of great significance. While the patrilineage is a community of men who live together, venerate the same ancestors and, in the past, fought together in a unified army against enemies not belonging to their clans, matrilineal connections stem from one individual and refer to people who live outside of the residence area.

Upon asking a Bulsa friend a question like, “Do you know this Mr. or Mrs. A.?” I was often answered with, “Oh yes, he is my nephew” or “She is my aunt” or even with an English neologism like “We are uncling his family”. This phenomenon has very practical consequences. If a Bulsa comes to another Bulsa village, he is expected to visit his uncling house or the family of his nephew to renew family relations. For this reason, it is advantageous to have a good knowledge of one’s matrilineal relatives. The late Sandemnaab Azantilow, for example, not only knew his mother’s (Awusima) parental village (Siniensi), but also his mother’s mother’s (Gbedema), his mother’s mother’s mother’s (Kanjaga-Jininsa) and his mother’s mother’s mother’s mother’s (Kanjaga-Piisa) origin, although he could not tell the names of the old ancestresses. If a Bulsa is in a big town outside Buluk in search of a sleeping place and he does not find the residence of a patrilineal family or (in modern times) a classmate, he is welcomed by the family of his matrilineal relatives.

In 1982 (p. 40) I tried to compare matri- and patrilineal ties using the image of a “cobweb” structure, and I still think that it is quite an appropriate method of showing the relations of a single male person in the centre of this web.

The concentric threads of such a web can be compared with the patrilineal lineage segment surrounding the ego in circles of varying sizes. The radial threads symbolize the matrilineal kinship ties, which in the central part of the cobweb are stabilized by concentric threads (patrilineal ties).

This demonstrates that patri- and matrilineal ties are indispensable components of the traditional Bulsa society. "Though patrilineal descent is overwhelmingly dominant in the jural, economic and ritual constitution" (Fortes 1969: 30), the main function of matrilineal relations is probably the construction and maintenance of forgotten ties to these lineages.

References

Fortes, Meyer (1969, 1st edition 1949): The Web of Kinship among the Tallensi. London: Oxford University Press.

Kröger, Franz (1982): Ancestor Worship among the Bulsa of Northern Ghana. Religious, Social and Economic Aspects. Kulturanthropologische Studien, vol. 9, Hohenschäftlarn: Klaus Renner.

Kröger, Franz (2013): Das Böse im göttlichen Wesen. Der Mungokult der Bulsa und Koma (Nordghana). Anthropos 108,2: 495-513.

Kröger, Franz and Barbara Meier (2003): Ghana’s North. Research on Culture, Religion and Politics of Societies in Transition, Peter Lang Verlag.