|

|

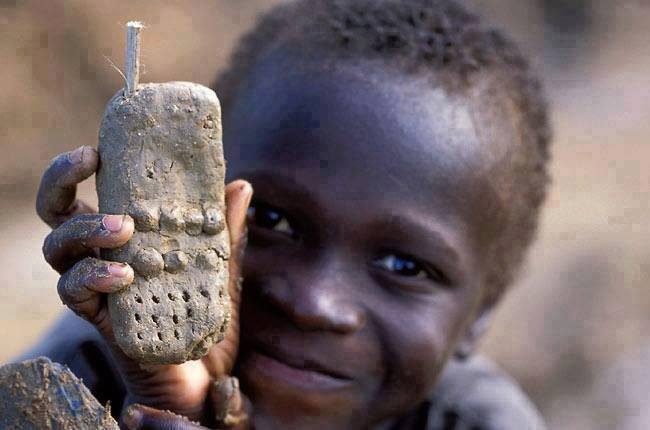

Mobile Phones in Uganda's Capital, Kampala. Source: Killian Fox in "The Observer" July 24, 2011 |

Marcus D. Watson:

|

|

Mobile Phones in Uganda's Capital, Kampala. Source: Killian Fox in "The Observer" July 24, 2011 |

CELL PHONES IN BULUK:

DO THEY DISCONNECT US IN THE NAME OF CONNECTING US?

INTRODUCTION

While conducting research on digital technologies in Buluk over the summer of 2012, I couldn’t help but notice that cell phones and internet applications such as Facebook and Skype seemed to separate people. This was shocking since I had imagined my study in a much different way. I anticipated seeing all Bulsa, but especially the youth, holding digital devices, communicating at breakneck speed with loved ones near and far. I now realize that I may have overestimated the number of digital users, though cell phone use in particular was quite high. I also realized that the commonsense assumption that cell phones do nothing but connect people is simplistic and may even be the opposite of what is true.

In this article, I expand on this finding so that those committed to the wellbeing of Buluk can consider the implications of cell phone use for the cherished homeland. How is the use of digital technologies, especially cell phones, impacting Buluk? If cell phones connect distant individuals, do they also disconnect those who remain in face-to-face contact? Accompanied by my wife and her cousin, both of whom are Bulsa born in southern Ghana, I spent two months asking these questions of a diversity of individuals. To get answers, I interviewed the research participants and participated in their lives as a way of observing “first hand” how cell phone use impacted their interpersonal relationships with those who remained physically present.

Since it became clear that the commonsense idea about cell phones helping people to stay connected was simplistic and unhelpful, I turned to academic theory for a more convincing explanation. The first thing to be explained was why everyone, including most of the Bulsa research participants, accepted the idea of cell phones uniting people without question. Drawing on the work of communications scholar Paul Taylor (2010), my answer is that people are so focused on what digital devices can do that they don’t think about their deeper implications. Stated academically, this is the problem of being so dazzled by something’s appearances that we fail to realize that there may be a serious problem with it at a deeper level.

Consider a famous analogy as a way of shedding light on this idea: A factory worker is suspected of stealing. A security guard is charged by management with investigating the matter. Each night, the guard inspects the worker’s wheelbarrow, first from a distance and increasingly from closer proximity. The guard finds that the wheelbarrow is always empty. Weeks later, the guard and management realize that what the worker has been stealing all along were the wheelbarrows (Taylor 2010: 10). This is what I found in Buluk — individuals so focused on the calls and messages coming to their cell phones that they hardly had the time or the interest in thinking more deeply about the impact of the devices on interpersonal relationships or on Buluk.

Since commonsense is a poor explanation for understanding cell phone use in Buluk, I turn instead to two academic theories: affordances and political-economy. Based on insights from these theoretical traditions, I found that the net effect of cell phone use was to nudge individuals toward experiencing themselves and their bodies as disconnected from others, including those who were physically present and those who were in distant locations. Since capitalism is largely based on the forced separation of people and bodies (e.g. Lowe 1995), cell phones are one of capitalism’s newest and perhaps most effective agents, carrying out their mission by dazzling users who cannot imagine living without them. It’s time to reimagine commonsense.

|

| Source: Radio Netherlands Worldwide. December 13, 2013 |

REIMAGINING CELL PHONES: AFFORDANCE THEORY

The first thing that must be reimagined is the cell phone. It is not just a little black thing that people use as they see fit. Like all things, the cell phone affords certain kinds of thoughts and behaviors for certain kinds of living beings. To better understand this, think about a stagnant pond - it’s a good place to stand for a mosquito, to wallow for a hippopotamus, and to drink for a lion. Not so for a human being, however, who instead may find the pond suitable only for skipping rocks (Gibson 1977). Similarly, when we see a door knob, we reach to turn it; however, if it was a doorplate that we saw, we would have pushed it (Norman 1988).

What we usually see as “just things” have “invitation character.” (Dant 2004) That is, things have qualities, such as their dimensions, temperatures, and functions, which invite a range of thoughts and behaviors for different kinds of living organisms. As the examples of the doorknob and doorplate suggest, “invitation character” can be built directly into human-made crafts. This doesn’t mean that each person accepts the invitation in the same way or at all. There is still human choice, but the choice is not “free.” Our choices are obliged to maneuver around “things” which call for certain kinds of behaviors and thoughts.

What does the cell phone call for? What is its invitation character? The answer is clear. It calls the human being away from face-to-face communication and towards faceless or virtual communication. Its quality of being easily-held-and-used facilitates its function, which is to beam voices across vast spaces in an instant. Because users are often far apart in space, they are blind to each other’s situations at any given moment in time. Thus, if the cell phone invites the human being to embrace faceless forms of communication, it also invites him or her to disregard the importance of other people’s “context” in human relations.

The cell phone is calling us to experience ourselves, others, and communication in these ways, even if we respond to the call uniquely. Thus, a person who doesn’t want to interrupt an event may turn off his cell phone’s ringer. But this doesn’t “turn off” the phone’s invitation to pick it up and beam one’s voice across space. Similarly, a person may choose not to answer her phone when it rings, but the phone is calling her to answer it nonetheless. When it comes to a cell phone, the human being is in a relationship of mutual influence; the human being does not dominate the thing because the thing also has a stance.

BULSA AND CELL PHONES IN EVERYDAY SITUATIONS

In my research, Bulsa spoke of cell phones in various ways, although most saw them as indispensable in their lives. Even individuals who didn’t own phones

|

|

Source: BMY Facebook Discussion Group

|

owned SIM cards, which they inserted into friends’ phones to make calls. Owners of phones always carried their devices, even into bathing areas, where they could answer calls and prevent others from using their phones. Expressing a minority opinion, some middle-aged parents from poorer backgrounds criticized cell phones for exposing children to unsavory images and distracting them from household chores. Most, however, said that the pros of cell phones outweigh the cons.

Many Bulsa said they used phones to communicate with business partners and professors in Buluk or in distant urban areas, such as Accra. Several Bulsa men spoke of using phones to keep in touch with multiple girlfriends, some who lived in Buluk and others who lived in Southern Ghana and even overseas in places such as Canada. To avoid mixing “work” and “play,” interviewees often used different SIM cards for professional and personal calls; some even used different SIM cards for different romantic partners. Nearly all interviewees used phones to surf the internet to check email and befriend on Facebook; some searched for pornographic images.

At the level of appearances, there is nothing controversial going on here. However, appearances are not everything. Consider this snapshot: While chatting with three individuals in their mid-twenties at a restaurant table in the town center of Sandema, Atisi’s phone rang. He swiveled in his chair to better reach the phone in his pocket, drew it out, looked to see who was calling, answered the phone while standing up, and walked to roadside to hold a conversation. As he approached the roadside, he did not hear a middle-aged man greeting him. No other passersby tried to greet him. Atisi returned to the table without any mention of the received call or caller.

In this scenario, Atisi’s choices were not free and his cell phone was not powerless. In its design and functions, the cell phone afforded Atisi the choices of leaving the face-to-face interaction or remaining in it. Further, the choice was stacked in favor of leaving the interaction because the phone was, literally and figuratively, calling him to do so. Stated differently, the digital device imposed the choices onto Atisi and also ranked them according to a hierarchy of value: moving from face-to-face to virtual communication, from fully present to half present, from embodied to verbal, was what was called for.

Let’s look at this situation again, this time seeing how the phone call directed Atisi’s body. When Atisi’s phone rang, his body swiveled away from the other three Bulsa and me. By the second ring, Atisi’s hand had reached the phone in his pocket and was pulling it out. The phone had fully captured his attention as he peered down at it to identify the caller. As the phone drew Atisi away from the table, we let him go, continuing our talk without his immediate presence. As Atisi transitioned to the road side, his attention was so steeped in the conversation that he was oblivious to the passing man who was greeting him. No passersby interrupted him thereafter.

Digital devices like the cell phone are human-made and thus carry the cultural logic of their producers. It is important, thus, to understand that, when we see a person holding a cell phone, what we are witnessing is a cultural encounter. Atisi may have thought he was making free choices, but this is clearly false. He accepted the phone’s invitation to leave the face-to-face interaction, but he wasn’t responsible for being invited. In fact, the cell phone and its invitation won: not only did Atisi give in to their logic but they also seemed to draw an invisible bubble around him, as if he was “off limits” while he talked.

This is an ironic phenomenon since cell phones are commonly thought to connect people whereas, when actually studied, they appear to produce the opposite effect. It might be argued that users such as Atisi connected with the person who called them. But think carefully about this point. What sort of connection was it, really? Generally speaking, if the phone helped Atisi and the caller to hear each other’s voices while keeping them at a physical distance, we might call this a half-connection. Specifically, the cell phone’s ability to zap voices across spaces in an instant is predicated upon a radical separation of bodies.

The radical separation of bodies is the building block for interactions involving cell phones. For example, Atisi responded to his ringing phone by physically getting up and going away from the bodies of those with whom he was talking. Further, being on the phone seemed to make others perceive his body as momentarily unapproachable by their own bodies. Since the cell phone brought Atisi’s and the caller’s voices into contact, it might be argued that their bodies actually came closer to each other. The paradox, however, is that the experience of “voice contact” only reinforces the great distance between the bodies of the speakers.

BULSA AND CELL PHONES IN LARGER CONTEXT

Under the cover of promising to keep loved ones together, the cell phone is sewing greater seeds of distance between them. This is unmistakably a capitalist phenomenon, since capitalism is famously premised on alienating human beings from each other (Marx 1988/1844). The iconic image of capitalist alienation is the industrial factory, where each individual focuses on the machine and levers in front of him instead of on individual at his side. But capitalism’s need for alienation and body separation has now extended beyond the industry. Think, for instance, of modern entertainment, where multiple individuals view a screen instead of each other.

In its colonial form, capitalism was brutal in its demand for alienation and body separation. South Africa’s apartheid system is an extreme form of the brutality. Think of members of ethnic groups forced to live separately within “homelands.” Also recall how the demand for Congo’s rubber led to coercing men to labor in the forests or risk having their women stolen and raped (Hochschild 1998). National borders are designed to separate one social body from other social bodies. To make people move into work camps, national parks separated human and animal bodies. Migrant labor uses the lure of money to draw human bodies to faraway places.

During colonial times, much of the body separation had to be coerced or forced against the better judgment and will of the Africans involved. Today, however, Africans, following a global trend, are in a rush to aid capitalism’s demand for interpersonal alienation and radical body separation. What I dare us to appreciate is the role the cell phone plays in satisfying the demand. If force “from above” was the old method of alienating Africans from each other and their lands for the sake of organizing for capitalist production, the new method occurs “from below.” Or, to use more fitting imagery, the new method is “hand-held.”

Blinded by the dazzling power of the cell phone to zap voices, messages, and images across great distances, users purchase the devices and dare not live without them. What users don’t consider is that they are not just purchasing access to the dazzling content afforded by the cell phone but also its deeper impacts. As a form of communication, the cell phone turns its user away from others, ring by ring. In doing so, it subtly trains the body to accept alienation as a natural state of affairs. As such, it is capitalism’s newest and perhaps best ally, getting Bulsa to invest their own money toward becoming the laboring bodies it needs to function.

CONCLUSION

This research is just beginning, but it is already clear that the idea of cell phones connecting people is simplistic; it does not reflect what is happening in everyday reality. Reality seems to be just the opposite—cell phone communication depends on a subtle disconnecting of persons and their bodies, which are the overlooked building blocks of global capitalism. We need to become more critically aware of what cell phones invite us to do and how we react to the invitation. Do our cell phones help us connect with faraway others, or do they trick us into participating in the disintegration of the relationships right in the heart of Buluk?

Even if it was accepted that cell phones plant seeds of alienation right in the heart of Buluk, it is still unlikely that anyone would change their way of life to resist the problem. In fact, everyone I interviewed seemed to share the sentiment of a professional woman named Azangbapok, who said, “I can live without some things but not my cell phone.” Accepting a bit of alienation in order to enjoy the thrill of instant communication reminds one of Walter Benjamin’s words about the state of humankind a century ago: “Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order” (2010/1936: Epilogue).

Where do we go from here? Are we convinced of the problem? Should we walk around Buluk and see for ourselves how cell phones and internet-use invite us to shift away from face-to-face relations? Do the benefits of communicating at a distance outweigh the alienation creeping into face-to-face relationships? The questions should be taken seriously, especially in light of attempts by Bulubisa Meina Yeri to resurrect the image of Buluk in the eyes of Bulsa youth. Youth are searching for greener pastures outside of Buluk, but how are they informed about the greener pastures? What is orienting their vision into the distance? What is calling them there?

References

Benjamin, Walter. 2010/1936. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Prism Key Press.

Dant, Tim. 2004. The Driver-Car. Theory, Culture and Society 21(4): 61-79.

Gibson, James J. 1977. The Theory of Affordances. In, Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing: Toward an Ecological Psychology, edited by R. Shaw and J. Bransford. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hochschild, Adam. 1998. King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Mariner Books.

Lowe, Donald M. 1995. The Body in Late-Capitalism USA: Post-Contemporary Interventions. Duke University Press.

Marx, Karl. 1988/1844. The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto. Prometheus Books.

Norman, Donald A. 1988. The Psychology of Everyday Things. Basic Books.

Taylor, Paul A. 2010. Zizek and the Media. Polity Press.