|

|

|

Children playing the "family game" |

|

Franz Kröger

Miniatures in Bulsa Religion and Magic

Miniaturized depictions of reality are indispensable in every culture and appear as photos, drawings, paintings, sculptures, etc. They allow us to look at the real world from a different perspective, thus giving us a better, static and unchanging overview of a situation and objects.

Miniatures in a Secular Context

In Bulsa society, three-dimensional miniatures play an important role. Bulsa children love to create images of the surrounding adult world. They are excellently

|

|

|

Children playing the "family game" |

|

skilled in replicating, in

miniature size, all possible objects found in their environment. These objects include small

clay or plastic pots and bowls as well as dolls (their children), which are made of clay; other objects

include mats made of grass stalks and leather aprons made from mice skins. They find

suitable applications and functions for them in the ever popular "family game" in which girls

assume the roles of mothers and housewives while boys go hunting with small bows and

hand catapults and sometimes really kill a bird, a lizard or a mouse. Such games may take

place over many days.

Often practical reasons play a role for creating objects in a reduced size. In Kenya, a seller of

souvenirs complained to me that his customers preferred to buy copies of musical

instruments, pottery, figures, etc. in a size smaller than that of their ordinary usage in

everyday life. This was because the instruments had to fit into the luggage of tourists who

|

|

|

Miniature vessels |

|

did

not want to exceed the maximum weight allowed for a flight.

Perhaps such concerns were also at play when a Bulsa potter offered me two fired ceramic

vessels in a size corresponding to about one-eighth of the ordinary size. She also proposed

moulding the entire inventory of the ceramic objects found in a Bulsa household in this

reduced size for me. The value of such a collection would be limited, but I suspect that in the

present small collections (e.g. in ethnological institutes) the average size of the objects is

below the standard measure.

Miniature Weapons

In this article, detailed investigations should be limited to miniatures that have been made

solely or primarily for ritual or magical reasons. Reductions are usually accompanied through

stylizations in the presentation of the small objects.

|

|

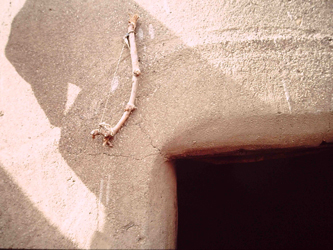

Bow of a new-born boy |

Sometimes the exact meaning and purpose of the objects produced has got lost, even in the minds of Bulsa. Three days after the birth of a boy, the landlord or father of the boy produces an approximately 30 cm long bow (biliok tom) from a millet stalk which is unlikely to function because of its fragility. The bow in my possession is made from a branch of the Nim-tree (Azadirachta indica) while the bows of Bulsa adults are made of bamboo or yuelik-wood (Grewia lasiodiscus). A thin stalk and a nail with the head removed or bicycle spoke instead of a barbed iron top are used to represent the arrow. Such a bow remains hanging on a wall

|

|

Miniature quiver and arrows |

in the inner courtyard of the baby’s mother for a few weeks until it is disposed of. They

could not give me any precise information about the meaning of this custom, but it probably

implies that the little boy should become a brave warrior or skilled hunter in his adulthood.

In the estate of the late Prof. Rüdiger Schott, there was a round quiver of about 16 cm in

length, and it contained seven arrows made from thin stalks and topped with arrow heads

probably cut from a black plastic sheet. Apart form its size, the miniature quiver resembled a

real quiver in many details. Nothing more could be learned about the original function or

meaning of these objects, but there is probably an association with ancestor veneration.

Code Objects of a Diviner

The symbolic objects in the bag (baan-yui) of a Bulsa diviner (baano) reflect the whole

religious and secular milieu of traditional and, at least partly, modern society. Cultural

phenomena and objects represented by small, stylized images as code objects are used in the

divining sessions. Such reproductions in wood (e.g. from branches) or gourd shards are

carved by the diviner himself. For adequate usage, the diviner has to find an overall meaning

for such objects, and these objects will, in the diviner’s instructions, then be imparted with a

practical meaning related to the client’s daily life.

|

Bild |

Buli Name |

The material code-object |

Meaning of the code-object |

Instruction for the client (for example) |

|

|

chiik |

calabash moon |

month |

Perform the ritual within one month’s time. |

|

|

nantuok |

branch in the shape of a foot

|

foot |

You will travel. |

|

|

guri |

small wooden mallet

|

tool with which earth spirits kill |

Somebody will try to kill you. |

|

|

gbain |

piece of leather/skin |

cowhide for sitting; wealth, relief

|

You will be rich (relieved). |

|

|

su-paksa |

cross scratched into a calabash sherd

|

crossroad; where two footpaths cross |

Perform the ritual at the crossing of two footpaths. |

|

|

nipuuk |

two calabash pieces

|

clapping hands, thanks |

You have to thank somebody. |

|

|

wen |

round calabash sherd |

wen, wen-bogluk |

You have to perform a wen-piirika ritual. |

|

|

nurba noai |

calabash sherd with serrated edge |

mouth of people |

People talk about you - gossip

|

Often the desired code object is not produced by the diviner himself, but he finds it among secular everyday objects which have a certain similarity to the desired object.

|

pein |

iron nail |

arrow |

Somebody tries to kill you. |

|

|

|

wiik / yuik |

small iron tube |

whistle |

"They will play the whistle on you" (i.e. they will humble you).

|

|

|

nyu-vuri |

sp. fruit |

nose, breathing |

You will live (a long life). |

|

|

nyu-vuri |

modern button |

nose, breathing |

You will live (a long life). |

|

|

nansiung |

ring of metal |

gate, entrance |

Perform the ritual at the entrance of the compound. |

In some code objects, the original idea (e.g. disease, agreement, health, etc.) is no longer

recognizable without explanations, and in some instances they can be referred to as true symbols.

|

|

nying-doma, nying-tuila |

perforated calabash sherd |

disease (the soul is perforated) |

This concerns the disease of a living person. |

|

|

noai yeng |

round calabash sherd with a slit or notch |

"one mouth", agreement |

Try to find agreement with an enemy. |

|

|

kambieng |

small shell |

coolness, health |

You will be healthy. |

|

|

jiuk |

small fly- whisk |

chieftaincy, power of an elder |

If you comply, you will become powerful. |

|

|

laata |

lower jaw-bone of a mammal (dog) |

laughter, happiness |

The affair will find a happy end. |

Most code objects correspond to the principle of "pars pro toto" (i.e. a part for the whole). In

particular, the instructions to sacrifice certain animals are dictated by means of specific body

parts of these animals: the feet or feathers of chicken or guinea fowls or the horns, feet or

hooves of animals such as goats, sheep, cows, etc.

Jadok-spirits and Ancestors

|

|

Jadok relief on a wall (below there are personal shrines of living people) |

Even for an expert on the Bulsa religion, it is sometimes hard to figure out what category of supernatural beings a certain shrine-spirit (bogluk) belongs to. Such an assignment is, however, not very difficult for a certain type of ngandoksa (sing. jadok), which are spirits often associated with animals. They seek contact with people in various ways with the intention of being venerated and offered to. Their shrines may consist of small mud mounds or big conical mud constructions. But mostly they are venerated in relief figures on a wall, on the floor or on a flat roof. The figures often take the form of animals such as chameleons, lizards or snakes. Such a representation of an animal is almost always surrounded by an annular mud relief, which is the "wall" of its compound. An opening of this ring to one side represents its entrance (nansiung).

In Agbandem Yeri (Zamsa) all ancestors of the compound are venerated in a large round mud shrine with about 60 stones serving as offering spots. In the middle of the shrine, the sacrificers have built a small compound with several rooms (diina, sing. dok) for the

spiritual inhabitants. At first glance, however, a foreign visitor sees only a disorderly heap of thorns, which serve a very practical and non-religious purpose:

|

|

| Ancestral shrine in Zamsa | Tiili between two big ancestral shrines |

The thorns keep poultry and goats

from destroying the labouriously erected miniature structures but do not hinder the ancestors

from entering their small homesteads undisturbed. The buildings not only serve to provide

the ancestors’ with comfort but also to further convenient communication among them.

Small Bulsa compounds on large ancestral shrines seem to be very rare in other Bulsa

villages. The idea of facilitating an unhindered communication among the ancestors is,

however, quite often realised through massive mud “bridges” between the shrines called tiila

(ladders, sing. tiili) in Buli. Big wooden ladders, which have become rare today, were used

by the residents of a compound to climb over the walls of inner courtyards (e.g. of the

landlord’s wives) in order to develop friendly relationships among the inhabitants.

Miniatures for Deceased People without Ancestral Status

|

|

Garment (smock) in infant-size |

Although the Buli-name for ancestors (kpilima) is etymologically related to kpi (to die), we

have to distinguish between deceased persons, for whom the last funeral rites have not been

carried out, and genuine ancestors. The former do not have an ancestral shrine, but they can

make certain demands of their living relatives. As I explained in my article on the ngarika-burial (Buluk 9), the Bulsa pay particular attention to applying the same ritual treatment to all

dead family members. For example, if descendants of a recently deceased person want to

bury him in full traditional dress (garuk), they must subsequently open the graves of close

patrilineal relatives (who were buried naked) in order to offer them this dress. too. These

garments, also called smocks in Ghana, are often in very bad condition and no longer

wearable for survivors. New smocks would be beyond the financial limits of some

descendants. If no older smocks can be found in the homestead, they can also purchase

miniature–sized ones in the market that would be suitable only for a living infant or baby.

Miniature Items for Spirits and Living people

It should be examined whether the reduction in size of tangible objects is also common or at least possible when these objects are used by both spiritual powers

|

|

Akanming's shrine objects including the small wooden mallet |

and living people.

On the shrines of earth spirits (tanggbana), full-size wooden mallets (gue, sing. guri)

function as weapons with which a tanggbain may kill his or his human owner’s enemies. I

have never seen a miniature mallet on such an earth shrine. However, the old (and now

deceased) landlord Akanming kept something like an offshoot of a tanggbain in his ancestral

room (kpilima dok or dalong). In addition to a lump of earth, Akanming also kept a miniature

guri, represented by the corresponding portion of a thin branch with which the tanggbain

should kill his enemies. Here the guri had once again become a smaller version of the real

thing but was regarded, symbolically, as being as effective as the full-size version.

Conclusion

Conclusions about the qualities and characteristics of ancestors as regarded by the Bulsa can be derived from the facts described above.

When discussing matters of ancestry, it is necessary to determine which part of the ancestral personality should be focused on during ancestral veneration. Is it his dead body? Is it his soul (chiik) which walks to the realm of the dead after the second funeral celebrations? The receiver of sacrifices is the ancestral wen, which resides in the sacrificial stone of a shrine. In contrast to the soul (chiik), the wen was never inside the ancestor’s body while he was alive, but in a personal shrine (tintueta wen) where it was worshipped and given offerings. Although wena (pl.) are actually a part or aspect of God the Creator (Wen or Naawen), human characteristics are also attributed to them. For example, they require, albeit less frequently than humans, food and drinks that are given to them in sacrifices. Normally the ancestral wen slumbers in the globular sacrificial stone and is woken by the sacrificer, who puts his hand on the stone or pours some clear water over it saying, "A. [Ancestor's name], boro-o?" This translates to "A., are you here?" or "A., are you alive?"

Although wena can leave their stones, it should not be inferred that they are usually roaming

about. They can reach their descendants in all parts of the world and also influence them

without leaving their stones. A landlord (yeri nyono) compared this way of contact with a

telephone. However, this does not allow any direct influence on the destiny of the listener as

is possible with the Bulsa spirits.

The miniature homestead of Zamsa, too, assumes that the ancestral wena can leave their

stones and communicate with others in their “miniature houses". The smallness of the

buildings should not tempt us to attribute smaller body sizes to the ancestors. They are pure

spirits and as such not subject to body measurements.

Generally speaking, we can say that reductions of size in the religious sphere are not

necessary for proper communication with and among the ancestors and other spirits.

However, a reduced and stylized image presents no obstacle to communicating with them

and is easily recognized by the spirits in its desired meaning and function.

References

Franz Kröger

Wahrsager / Divination. In: www.Ghana-Materialien.de

—, 2001: Materielle Kultur und traditionelles Handwerk bei den Bulsa (Nordghana). Forschungen zu Sprachen und Kulturen Afrikas (Ed. R. Schott), 2 vol., Lit-Verlag, Münster and Hamburg.