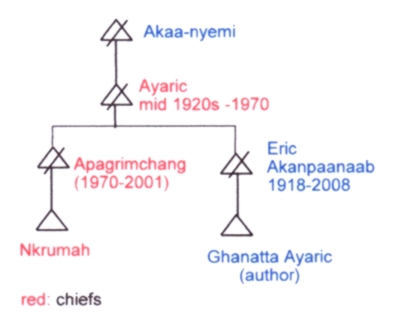

Ghanatta Ayaric

CHIEFTAINCY IN GBEDEMA

Tong-naab and Zutok-muning-naab

Like the monarchy in many parts of Europe and elsewhere in the world, chieftaincy is an old institution in Ghana.

|

|

A new Bulsa chief is crowned with a red cap under the Sandemnaab's royal umbrella |

When the Europeans first arrived in the Gold Coast, as early as 1482 with the first Portuguese settlement in Elmina, chieftaincy had been in existence. And by 1901 when the British colonial government of the Gold Coast established the Northern Territories (North Ghana), chiefs and teng-nyam were already playing important roles in the lives of their people. Assisted by their councils of elders, they took decisions that were aimed at ensuring the rule of justice, peace, unity and prosperity in their societies.

In the Northern Territories of Ghana, as the case was in Northern Nigeria, notably in Kaduna, Kanu and Sokoto, where the sultans, for example Ahmadu Bello, were very powerful rulers to be reckoned with, the British were quick to realise that they would be unable to establish and consolidate colonial rule if they bypassed the chiefs. Political expediency dictated collaboration, the result of which was the famous or rather infamous policy of Indirect Rule, the propagation of British colonial policy using traditional rulers as active instruments. In core, Indirect Rule was a subtle subjugative policy put in place to promote British interests and guarantee the success of colonial rule.

Among the Bulsa, the symbol of a chief’s title today is his zutok-muning, red cap (without the curved part which sticks out at the front of the conventional cap), which he receives from the paramount chief, Sandemnaab, on the day of his installation.

|

|

|

Chief Apagrimchang Ayaric |

Chief Nkrumah Apagrimachang |

The history of zutok-muning chieftaincy in Gbedema began with Chief Ayaric of Gbedem-Gbednaasa (Gbinaansa) who ruled from the mid 1920s until his death in 1970. Chief Ayaric was succeeded by his eldest son, Chief Apagrimchang Ayaric, who ruled from 1971 to 2001, the year of his death. The current chief is Nkrumah Apagrimchang Ayaric.

The Ayarics of Gbedema have not always been a family of chiefs. Chief Ayaric’s father, Akaa-nyemi, was not a chief. He was an ordinary man, but a wealthy farmer with many farms and a big herd of cattle and other livestock, and a respected man, not only in Gbedema, but in the whole of Buluk. Proof of his status as a distinguished personality in Bulsaland was his friendship with the Sandemnaab at the time, Chief Ayieta Ananguna, Chief Azantinlow’s father.

According to my late father, Eric Akanpaanab Ayaric (1918-2008), who passed the

information contained in this paper on to me, Ayaric, his father, was the only child of his

mother, a man who was able to establish himself early in life as a hardworking and successful

farmer, a generous, reliable and thoughtful person, who neither indulged in alcohol nor

women, unlike some of his step-brothers and other young men in the extended family. This

endeared the young Ayaric to his wealthy father who then chose him as his personal

messenger in matters concerning correspondence and communication with people outside

Gbedema including Sandemnaab Ayieta. In the course of his frequent visits to the Sandema

royal palace, Ayaric befriended Afoko, who later succeeded his father, Ayieta, as

Sandemnaab, a friendship that was to play a role in Ayaric’s subsequent installation as first

zutok-muning chief of Gbedema.

Until the enlection of Ayaric as chief of Gbedema by Sandemnaab Afoko (Sandemnaab from 1912-1927), the form of traditional leadership that existed in the village was spiritual in nature and in the person of the Tong-naab, an intermediary between the Tong-bogluk [the Tong-naab-bage, one of the ancestral shrines in Tengzuk, the most important shrine (ngiak) a few miles north of Tongo], and God on the one hand, and the spirits of the ancestors and people of Gbedema on the other hand. The title Tong-naab is derived from that shrine-name. As a rule, the Tong-naab has always been a member of the family of the compound in Gbedema popularly known as Nakpak-yeri (old-chief’s compound), a fact that has never been disputed in the village. The Tong-naab is recognised and respected as a spiritual leader and the person to be consulted on religious matters. His role, even today, is exclusively spiritual and he is answerable only to the Tong, ancestors and God.

Before Ayaric became zutok-muning chief, the Tong-naab also functioned as an informal representative of the village at the district level even though he himself was not very comfortable with that role. He preferred to focus more on his spiritual duties and rarely went to Sandema to participate in official duties. But in order not to neglect the secular role that he was being called upon to play, he had a young man, Aboro, from his household family who always represented him there.

How Gbedem-Nakpak-yeri and the village of Gbedema came to be spiritually associated with the Tallensi is a topic that can be tackled in another paper. Suffice it to say that till today a group of Tallensi traditional sacrificers visit Gbedem-Nakpak-yeri each year and make various kinds of sacrifices on behalf of the ancestors and people of the village. On such occasions the whole village contributes foodstuffs and livestock for their upkeep and as presents after the ceremonies. My late father used to recall with amazement some of the wonders often exhibited at ceremonies on such occasions. The Tong sacrificers would prepare TZ on fireplaces mounted on thatched-roofs without these catching fire, while some slashed themselves with matchetes without injuring themselves. I haven’t witnessed a Tong worship ceremony myself and cannot tell if these magical feats still exist today or not.

|

|

Tengzuk: Tongnaab-cavern in the upper part of the hill |

Unlike the zutok-munig chief who is installed by and answerable to the paramount chief and invested solely with traditional administrative powers, the Tong-naab is elected by the Tengzuk-shrine and the spirits of the ancestors, after having been nominated by the elders of Gbedem-Nakpak-yeri.

The criteria for nomination are very strict. Only adult males who live upright lives qualify for nomination. Nominees must have proven that they are honest, generous, hardworking and have no record of violence, alcohol abuse, fornication or adultery. When nominated, each nominee is given a dry millet stalk which he plants towards the end of the dry season. The nominee whose millet stalk survives, grows and finally bears grain is revealed as Tong-naab through a sign given by God via the Tong and the ancestral spirits after sacrifices have been made to them.

The Tong-naab receives a black calabash cap, a black golung (a kind of tanga) and a tangkalung, a calf’s skin apron worn to cover the back, from the neck down to the thighs, partly covering one side of the body. From then on these become his official outfit. And for a period of three years he is not allowed to farm. He assumes his spiritual duties from the day of his ordination, makes sacrifices to the ancestors and God, seeks the spiritual welfare of the whole village and receives the Tong from the Tallensi sacrificers from Tengzuk each year.

Even though he’s the official head of the village, the chief of Gbedema does not take decisions, especially those referring to spiritual matters, without first consulting with the Tong-naab.

I stated earlier that until the installation of the first zutok-muning chief of Gbedema the Tong-naab also functioned as a representative of the village in district administrative matters, and that he had a young man, Aboro, from his household to do so on his behalf.

It is reported that in the course of time the Tong-naab became dissatisfied with Aboro. Among the causes for his dissatisfaction with the fellow were laziness, alcohol abuse and womanizing. These, in his estimation, made the messenger unreliable.

It was in these circumstances that the then Tong-naab asked the wealthy farmer and distinguished village personality, Akaa-nyemi, to help him find a reliable substitute for Aboro. Akaa-nyemi, recommended his own son, Ayaric. Recommending someone from another family could have been seen as egocentric, or an attempt to take away a source of labour force from another household, especially when it was farming season. Since his own son had been running errands for him to his satisfaction, Akaa-nyemi recommended Ayaric to the Tong-naab. And being no novice in the job, having already functioned as personal messenger for his father and met important personalities and chiefs including Ayieta and his successor, Afoko, his personal friend, Ayaric proved to be a good choice and lived up to expectation.

By that time Afoko had become Sandemnaab. As they interacted even more regularly the friendship between chief and messenger grew in strength. So, when the Commissioner of the Northern Territories, probably C.H. Armitage, decided to have a chief installed in Gbedema and sought the advice of Sandemnaab Afoko, the latter sent a message to the Tong-naab asking him help him find suitable candidates.

Naab Afoko didn’t send the message through his friend and messenger of the Tong-naab, Ayaric, neither did he ask him to candidate. He bypassed his friend and sent one of his own messengers. Most probably he didn’t want to be seen as trying to influence the choice of the Tong-naab by suggesting Ayaric as a possible candidate. Nevertheless, he was very certain, that the Tong-naab would recommend his friend as a candidate.

In his turn the Tong-naab informed the various sections of Gbedema and personally consulted Akaa-nyemi on the paramount chief’s request, advising the former to let him add Ayaric’s name as a candidate. Akaa-nyemi thanked the Tong-naab for the honour bestowed on him, but pleaded with him to drop the idea of Ayaric’s possible candidature. Akaa-nyemi argued that Ayaric was the only child of his mother and would not, in his estimation, fit in the role of a chief. A chief needed nyam (people), he argued, adding that he, Akaa-nyemi, was already old and Ayaric’s siblings (children of his, Akaa-nyemi’s, other wives) were not nyam enough to stand behind a chief.

|

|

Chief Ayaric (1920s - 1970) |

When the list of candidates reached Sandema, Naab Afoko was surprised and displeased that his friend’s name was missing. Without delay he sent another message to the Tong-naab enquiring to know why Ayaric was not on the list of candidates, putting up a case for his friend at the same time: he had been working very well with the messenger and had come to associate him with diligence, and thought Ayaric would make a good chief. The Tong-naab informed Naab Afoko that Ayaric was also his choice but the young man’s father had his reasons for opposing his son’s candidature which he, the Tong-naab, respected.

Upon hearing that Afoko sent a message to Akaa-nyemi reproaching him for daring to say Ayaric didn’t have nyam. Had he, Akaa-nyemi, forgotten that he, Afoko himself, was one of Ayaric’s nyam? Naab Afoko didn’t mince words with his displeasure about the situation. He threatened that he would keep his zutok-muning until Akaa-nyemi rescinded his decision and allowed Ayaric to contest the chieftaincy.

Desiring not to frustrate the paramount chief further, Akaa-nyemi finally gave in and his son contested the chieftaincy. His credentials as a successful farmer and a young man whose “eyes see ground” (wai nina alaa nya teng) won him a lot of support in all the sections of Gbedema. These, added to his friendship with the paramount chief and chief-maker himself, made him the favourable candidate and many houses “stood behind him” to make him carry the vote at the election. Ayaric’s election was done in the same way as the other chiefs – people from the various sections stand behind the candidate of their choice.

In his long rule as a zutok-muning chief of Gbedema, Ayaric is said to have encouraged his people to take their farming activities seriously and to shun laziness, stealing, womanising, alcohol abuse and other social vices. He is also said to have introduced a traditional law which forbade the people of Gbedema from marrying “wives” of Gbedema. If a woman married a Gbedema man and left her husband, she was still considered a “wife” of the village and could not remarry another Gbedema man. Till today the practice is still a taboo in Gbedema. This in part explains the absence of serious inter-sectional feuds in the village, conflicts which often have their roots in the practice of men wooing and marrying other people’s wives. In Gbedema Tong-naab and Zutok-muning-naab work hand-in-hand, the one according the other the respect due to his position and leadership.