Franz Kröger

Teaching at Sandema Continuation Boarding School (1973 and 1974)

Even from my youth, as a white man, I always dreamed of teaching at an African school. In 1973, this dream came true.

Sandema Continuation School in 1973

As a lecturer at the University of Cape Coast, I travelled to Bulsaland during the trimester break to collect material for my doctoral thesis on generational conflicts among the Bulsa. To do this, it made sense to establish contact with a Bulsa middle school that had just taken on the name ‘Continuation School’. It would probably, I thought, be difficult to get permission to teach there, and such an engagement would involve a lot of bureaucracy. Nevertheless, I presented myself at an educational office (I forget the exact name) in Navrongo and cautiously asked whether I could, perhaps, teach at a Bulsa school. The answer was astounding: ‘Yes, choose any school and report to the headmaster there.’ No questionnaire, no presentation of certificates or proof of practical experience! Hoping that a boarding school would offer the closest contact with students, I chose Sandema Continuation Boarding School.

During my first visit to the school, I met the headmaster, Mr Atiim from Kanjaga, who proved to be not only an exceptionally friendly and helpful colleague but also, as I later noticed, an efficient teacher and headmaster. Several students told me that he was also the most popular teacher. We agreed on the following timetable:

Tuesday, Form 2, Geography, 10.55 a.m. – 12.00 p.m.

Wednesday, Form 3, English Composition, 1.40 – 2.45 p.m.

Thursday, Form 2, English Composition, 10.20 a.m. – 12.00 p.m.

Thursday, Form 3, History, 1.40 – 2.10 p.m.

I was able to live in a detached bungalow designated for teachers, which my friend, the Rev. James Agalic, and I renovated by painting the entire interior and providing chasing furniture.

The School and Students

The school had teaching buildings for classes M1 to M4; four dormitories, also called compounds; a kitchen; a dining hall (which, at that time, was only used when it rained); and toilets and bathrooms for boys and girls, as well as an assembly area and, to the right of the access road, a sports field. The teachers lived in the teachers’ quarters, somewhat separate from the other buildings.

In 1973, there were 122 students in total, with about 30 in each of the four classes. They paid a school fee of four Cedis per year. School uniform, which consisted of a green dress for girls and a white shirt and khaki shorts for boys, was compulsory. A girl was once reprimanded for wearing stockings in her sandals.

Apart from a few Buli-speaking Kasena, all of the students were Bulsa. In 1973, there were no Presbyterian students and only one Muslim. The rest were either baptised Catholics or candidates being prepared for baptism by catechists from Wiaga or Sandema.

The following teachers taught at the school during my time there:

Class 1: Mr Atiim (Kanjaga),

Class 2: Mrs Veronica Akandema (Sandema Kori),

Form 3: Mr Asiedu (South Ghana, Ashanti?),

Form 4: Mr Kaluti (Frafra, Bolgatanga),

Arts: Mr Leander Amoak (Wiaga-Badomsa),

Crafts: Mr Paul Alujai (Kasena, Navrongo),

Science (including agriculture): Francis Agbogo (Kasena, Navrongo).

Prefects

In 1973, the school had a well-developed prefect system. The male senior prefect was Anankami Agbedem from Gbedema. He had been appointed by the teachers’ conference and could only be dismissed by the headmaster. To illustrate why this might occur, one female senior prefect was dismissed in 1973 because she had attended the Catholic Sunday mass in Sandema (not even a school service!) wearing long trousers.

Senior prefects could give orders to all other students and impose punishments, such as additional work on the school farms, but not corporal punishment. They also distributed the students among the individual dormitories, called other prefects to meetings and led the morning assembly. In addition to one male and one female senior prefect, there was also an assistance prefect, a garden prefect, a class prefect for each of the four classes and prefects for the dormitories, who recorded the attendance of all students in their respective dormitories every morning.

First Contact with Students

I don’t recall the date of my first day of teaching, but it was probably at the beginning of July 1973 (perhaps the 4th). What happened that day, however, I remember vividly. I wanted to be punctual, but on that day in particular, my watch went haywire. I arrived very late. Mr Atiim showed me, without irritation, to the building where I was to hold a class on the subject of English composition. As I approached the classroom, there was a deathly silence. I feared that the students had left because of my tardiness. In Germany, when a teacher is late, the classroom in question is easy to find: an indescribable noise and students running amok will surely lead the latecomer to their destination. At Sandema, I entered the classroom and found a full class of about 30 students. All were sitting straight and upright in their chairs with their hands on their desks.

I don’t recall the date of my first day of teaching, but it was probably at the beginning of July 1973 (perhaps the 4th). What happened that day, however, I remember vividly. I wanted to be punctual, but on that day in particular, my watch went haywire. I arrived very late. Mr Atiim showed me, without irritation, to the building where I was to hold a class on the subject of English composition. As I approached the classroom, there was a deathly silence. I feared that the students had left because of my tardiness. In Germany, when a teacher is late, the classroom in question is easy to find: an indescribable noise and students running amok will surely lead the latecomer to their destination. At Sandema, I entered the classroom and found a full class of about 30 students. All were sitting straight and upright in their chairs with their hands on their desks.

After greeting the class, I started with a teaching method probably common in classes on composition: the teacher introduces the topic, and each student writes an essay on this topic while the teacher goes from desk to desk and observes their progress. I had chosen the topic ‘My Life Story’ first because it would enable me to form a first impression of the students’ situations and because it would help them, later on, in writing the CVs they would need to apply for jobs.

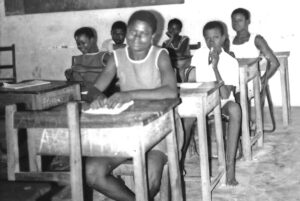

Form 2: On the left side of F. Kröger Mr. Asiedu and left of him Mr. Atiim

Mentalities of the Students

It would be interesting to examine how the mentality of my students at Sandema and their attitudes towards teachers, schoolwork and enjoyment compared to those of today’s generation of students. Unfortunately, I cannot. My comparison is necessarily with the students I remember from my teaching experience in German grammar schools.

As the behaviour of my first, patient class has already illustrated, the first thing I noticed was not only good discipline but also pronounced politeness towards teachers. Whenever I walked the approximately 100 metres from a school building to my residence, I was constantly approached by students, male and female, who wanted to carry my (not very heavy) bag. Whenever I called on a student in class, they would stand up, click their heels, put their right hand to their temples in a military salute and often answered, ‘Yes, sir,’ even if the answer was not quite apt.

The students showed an extraordinary amount of zeal in learning and consolidating the knowledge expected of them. Especially in the evenings before exams, small groups formed in the glow of kerosene lanterns to cram facts and skills acquired from lessons. Compared to urban schools, the exams went quite well. One student proffered an explanation for this: the Sandema students did not have as many opportunities for entertainment and fun (cinemas, parties, pubs, and so on) as the city students.

The Subjects Taught

According to the 1973 timetable, the following subjects (in alphabetical order) were taught at the school: arts, civics, crafts, English composition, English language, general science, geography, Ghanaian languages, history, mathematics, music, physical education, pre-vocational woodwork and religious instruction (by a catechist).

Not all subjects on the list were actually taught at the time. Ghanaian languages likely caused problems at all Bulsa schools due to a lack of teachers with sufficient Buli knowledge, especially of those who belonged to other ethnic groups. As a solution, the boarding school once had students tell Buli stories and riddles in front of the class. Otherwise, Ghanaian languages, which were not, an examined subject, were replaced by English language or composition.

Working on a cotton field

The Daily Routine

In 1973, I was able to create a Super 8 film of an arbitrarily chosen day in the life of the school, which served as a template for the following description.

After getting up, students took an obligatory full bath in a roofless bathing room away from the other buildings. Not all students had soap available for this. Subsequently, everyone met for breakfast, to be taken outside in good weather. The students received their food (see below) in vessels they brought for this purpose.

Assembly

Immediately after breakfast, a bell – or rather, an iron rail hung on a tree branch – was rung to signal the assembly of all students. One of the two senior prefects stood on a raised stone platform, gave information and instructions and said the morning prayer (with the sign of the cross). The teachers stood apart and did not interfere with the proceedings.

The teachers standing apart from the assembly. In the centre: Mrs. Veronica Akandema

After singing the national anthem and a march-like church song (such as ‘There Is Power in the Blood of Jesus’), the students marched to their classes in closed ranks. The afternoon school hours included the subject of agriculture, in which I observed, a senior student sprayed cotton plants with an insect repellent.

The time after classes ended was left to the students’ own arrangements. I observed some girls who staged Bulsa dances without musical accompaniment or devoted themselves to a then-popular South Ghanaian dancing game called Ampe. Another mixed group, gathered around a Mankala (bie duok) board to play. During my time at the school, visiting the European teacher (F.K.) was also an important part of this free time.

Food

While I was at the school, the students received three free meals a day. For breakfast, there was usually gari, the coarse-grained flour produced from fresh cassava roots, or a viscous millet porridge (kaponta or similar types). At lunchtime and in the evening, students were offered the Bulsa staple saab (a solid millet gruel) without meat or, more rarely, a rice dish. For major celebrations at the end of the school year, a goat was slaughtered. Often, students bought ingredients with their own money: sugar to add to the gari or kaponta or cans of fish for a hot meal.

Only once did I experience a complete lack of food. Even on the day after the last food had been consumed, no more had arrived. By the afternoon, almost all of the children were still calm, but some girls were crying. We decided to take my car and visit some wealthy or generous compounds to ask for grain. By the evening, we had gathered so much food that it lasted until fresh supplies came.

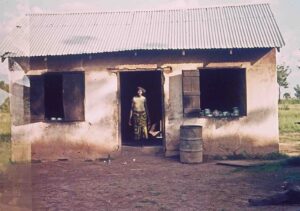

The kitchen

The school received most of its unprocessed food from organisations abroad. A smaller portion was earned through the labour of students and teachers on the school’s own farms: around 50% of the proceeds of that production were used to pay for the common meals (with the rest going to seeds, fertilisers and sprays).

Many students also worked their own fields near the school, but they themselves enjoyed little profit from these because the yields and the sales proceeds belonged to their parents, who also provided the seeds.

I was told that when food was scarce, some boys would walk for a long time to eat lunch at their parents’ compounds.

1974

During the 1974 trimester vacation, I resumed my teaching duties at the boarding school without relocating there. The focus of my teaching this time was on history. I did not try to explain political or ideological trends but compiled mock tests with specific questions, such as ‘What were the names of the three greatest leaders of the Russian Revolution?’ (Answer: Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin.) Coincidentally, almost this exact question appeared on the exam, an event which even gave rise to suspicions that I had secret connections to the examination board.

Conclusion

My teaching time at the boarding school yielded only a few new pieces of data for my PhD thesis, especially since the topic of generational conflicts had changed to that of rites of passage among the Bulsa. The students at Sandema had little knowledge of Bulsa rites because most had left their traditional homes at the age of five or six to attend boarding school.

Nonetheless, the time I spent at this school – together with my stay among a group of shepherds – belongs among the most impressive and nostalgic memories of my research experience. At informal evening gatherings of about a dozen students in my bungalow, not only were numerous songs sung in Buli and English captured on my tape recorder, but in free storytelling and conversation, I grew to know these young people, their lives and their problems. Long-lasting friendships were formed, and I remain in touch with some of my former students today.

- Three Educated Bulsa Generations

- The Bulsa and their political units

- Teaching at Sandema Continuation Boarding School (1973 and 1974)

- Fiok/Feok and Similar Bulsa Festivals