Franz Kröger

THE MEDICAL SYSTEM OF THE BULSA

1. Introduction: health, illness, medicine

For the Bulsa, health means more than just the absence of illness. It is an overall state of body and soul expressed by the term nying-yogsa (nying, body; yogsik, cool, wet, fresh). Illness is called nying tuila (tuilik, hot). The association of temperature properties like cold and hot with the two names may have been influenced by the fever that occurs in many tropical diseases, but the term nying tuila may also be attributed to a sick body without an elevated temperature. The terms “cold” and “hot” must therefore have a broader meaning, especially since they are also used for non-human phenomena. Tengka tuila literally means “the land is hot”. In a figurative sense, it also refers to areas in which armed conflicts take place and where there is any discord in the society. The human body can also become “hot” (tuilik) through personal excitement or a quarrel, and yogsik can mean “peaceful, calm, harmonious” as well as “cold, wet”.

Associations with the ideas of hot and cold play an intrinsic role in many transition rites, for in them the physically and emotionally unbalanced (“hot”) state of the ritual subject is transformed into a harmonious (“cool”, yogsik) state (Kröger 1978: 334). In a prayer that the diviner Akai (Badomsa) said during a wen-piirika ritual (see below), he requested five times that the child’s body should become cool (ibd.: … ate wa nyingka yok ngolola). It also can be ascertained from his prayer that the child’s “wen” has sent the “heat”. The child’s father (Leander Amoak) explained to me in English that “heat” referred to the sick state of the child, although, at the moment of the ritual, the child was physically completely healthy. Rather, his body was still “hot” from previous illnesses and especially from educational problems.

Some rites also express that the child’s body must figuratively be cooled down, for example, by pouring water over it. Examples for pouring water over a body include:

• the bath of a woman who has recently given birth and her child,

• the bath of the bride and groom with nipok-tiim water,

• pouring water over a woman who had left her husband and returned,

• pouring water at the initiation of a gravedigger (see below)

• pouring water over a pregnant woman before her pregnancy is announced.

Although physical cleansing is important in some of these rites, thoughts of religious absolution for old transgressions or cleaning a person from ritual impurity may also play a role. For example, the elimination of all pre-marital sexual guilt of the bride and groom is achieved through the common bath.

Some symbolic objects of a Bulsa diviner

Moreover, the use of ash (buntuem or tuntuem) in several rites probably has a symbolic meaning, because, as the previous hot state of the ash (burning, embers) was transformed into a cold one, so should it also happen with the personin the focus of the ritual. A detailed description of this phenomenon with references to further literature can be found in B. Meier (1992: 109ff).

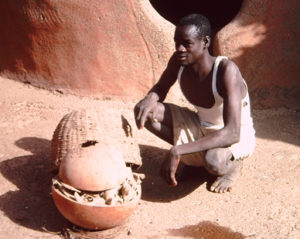

Among the symbolic objects of a Bulsa diviner, things associated with water or coolness often have a very positive meaning. For example, a shell (kambieng pak) means health (nying-yogsa) or coolness (yogsim); the head of a Nile monitor lizard (yuk), i.e. an animal that likes to live by or in the water, means happiness. Disease is sometimes indicated by a piece of slag (chiiri) from the iron smelting industry and has the symbolic value “heat, hot state”. Most diviners, however, have a perforated calabash shard (chinchiak le voana) for this which is supposed to symbolize the perforated soul of the sick person.

2. Health care

Although this has not been as pronounced in the traditional Bulsa society as it is in some European countries, its basic principles were not alien to the Bulsa before the beginning of the medical/hygienic education campaigns of recent times (endnote 1). Regular visits to the doctor for a general body check-up, blood tests, etc. when there are no signs of illness are very rare, even today. The mission clinic of Wiaga or the hospital of Sandema are mainly visited when traditional remedies have not helped or the feeling of discomfort has reached an unbearable level. The prevention of diseases and accidents is carried out by numerous magical means, which take the form of amulets, certain bracelets, defensive spells, etc. Nevertheless, there are measures which, from the point of view of modern medicine, can be described as preventive health care.

Hygiene

Although there is no word for “hygiene” in Buli, there is knowledge that infectious diseases are mainly caused by drinking contaminated water. Countermeasures are difficult to implement as long as there are no hygienic toilets and the fields near the compound are used in the mornings for defecation. In such cases, the human excreta can be flushed over or seep through the ground into the wells during heavy rain or flooding. A first measure against this was sleeving the shaft walls in cement. However, boreholes, which are becoming more and more common, are even safer. Parts of the bigger localities have access to clean tap water (Atinbil 2012:24).

One long-established measure against infection by harmful germs was the strict functional separation of the two human hands. The left hand, which is used when going to the toilet, must not be used, even by small children, for eating or handshaking. Traditionally, Bulsa wash their hands before and after meals by pouring water over them. Even before they sacrifice a warm meal to a shrine, they pour clear water for the shrine-spirit to wash his hands. A full bath by showering the body with water from a calabash bowl or a tin should be carried out every evening in the bathroom of one’s own living quarters. In the cold season (especially in January) the water is heated over a fire or (as I experienced it most of the time) by placing it in black containers in the hot sun of the afternoon. Especially in more recent times, traditionally produced or purchased soap is used when bathing (endnote 2).

External remedies against pathogens

Since the Bulsa know that many intestinal diseases are caused by germs in the water and fever diseases are caused by mosquitoes, they naturally also try to destroy these pathogens prior to their entering the human body.

Before the umbilical cord of a new mother is cut, the knife is heated. It is said that many users are unaware of this causing a complete sterilization.

The fight against fever-inducing mosquito bites was quite hopeless before the introduction of malaria prophylaxis and mosquito nets. In the early, mosquito-rich evening hours, people gathered in the inner courtyard or in closed rooms around fireplaces which produced a strong smoke after certain fresh leaves had been added. During the days and nights, one of my very old friends stayed on a branch construction about 70 cm high which also served him as a bed. Under this construction, a strong smoking fire burned at night to drive away the mosquitoes. More recently, chemical insect repellents and mosquito coils can be found for sale on the markets.

Germs in Buli On October 8, 2018 Lawrence Abakisi posted the following question in the Facebook group “Buluk Kaniak” : “Please, family, is there a name for “germs” in Buli?” |

Immunity

Particularly with regard to one’s susceptibility to malaria, a certain immunity to this disease sets in with increasing age. Infants benefit from their mother’s immunity until they stop breastfeeding. According to my information, the death rate of babies rises sharply after the end of the breastfeeding period when the mother’s milk (biisim) is very abruptly replaced by millet porridge (saab). Perhaps this is also one reason why the breastfeeding period lasted at least three years in the past.

I have only one piece of unconfirmed information about obtaining immunity to smallpox. It has been said that people used to get some fluid from the cow-pox and rub it into an open wound on their bodies to make them immune against human smallpox.

Vitamins

Just as in the case for “germs”, there was originally no word for “vitamins” in the Buli language. With regard to the importance of vitamins in public health, in the past there was probably no strong awareness of their dietary role. Consuming raw vegetables and fruit were very rare in the past. Nowadays, mangoes, pawpaws and peanuts are cultivated and play a role in the Bulsa diet. In the bush or, to a lesser extent, even within the residential area (endnote 3), they collect shea nuts from which only the outer green flesh is eaten raw before proceeding with the production of shea butter from the seeds. Other vitamin-rich foodstuff includes: Sunsuma (Gardenia erubescens), which is a yellow fruit, gaab (Diospyros mespiliformis), from whose dried fruits a juice (gaa-siita) is extracted, ngaara (blackberries, Vitex cienkowskii or Vitex doniana), which are only eaten fresh, and fruit of the tamarind tree (Tamarindus indica, Buli pusik), from whose seeds a refreshing, vitamin-rich drink can be produced (endnote 4). At the market (especially in Sandema), one can occasionally buy bananas or oranges.

Although it is well known that most vitamins escape from vegetables during cooking, they are not lost for consumption as happens in many European cuisines. Bulsa do not pour away the water used to cook the vegetables but instead use it for a sauce or soup (jenta). In cases where there are sick people in the family, it can be poured off and offered to the sick person as a drink (information from Gbedema).

In more recent times, the consumption of easily available vitamin tablets or those given by the doctor has risen sharply. I have noticed that the Wiaga Clinic often adds a pack of vitamin pills when tablets for other diseases are prescribed.

3. Medicine (tiim)

Definitions The Buli term tiim (pl. tiita) does not correspond completely to the English “medicine”. Tiim is a much broader term because it also includes material objects which are trying to influence a person without requiring any direct contact with him or her. Thanks to their magical power, they can also work over greater distances if they are meant to harm a certain enemy. In northern Ghana, the term “juju” has become established for these “magical means”, especially in the English language.

James Frazer (1963: 11) has shown fundamental differences between magic and religion. According to him, magic is a “spurious system of natural law as well as a fallacious guide of conduct; it is a false science as well as an abortive art”. By contrast, “religion is a propitiation and conciliation of powers superior to man, which are believed to direct and control the course of nature and human life (ibd. p. 50). Frazer admits that at an earlier stage the functions of priest and sorcerer were not yet differentiated from each other.

Also among the Bulsa there is no sharp separation between magical and religious actions. At least some tiita are fully integrated into religious rites, i.e. they receive sacrifices just like the ancestors, the earth shrine, the “tamed bush spirits” (ngandoksa), before sowing time and after harvest. They are, on this occasion, also addressed personally in a kind of prayer by the sacrificer. According to Robert Asekabta (in a letter) the beginning of a sacrifice to a tibiik might be like this:

“Ayieta tonangka fi dan sum boro yiri ngoa” (Ayieta’s medicine (shrine), if you [fi] are really there, get up and receive (the sacrificial gifts)…

In a sacrifice to shrines, the medicine is even offered clear water for washing its hands before the meal of millet porridge.

A tiim-bogluk (or tibiik, medicine shrine) can be an accessory of an ancestral shrine. Then it may include, for example, a clay pot with water and pieces of roots (endnote 5), the extract of which is drunk by the child for a few days after being named and given a protective spirit [see segrika in the chapter “Medicine and rites”].

If we define a shrine (bogluk) as a material object inhabited by a supernatural spirit or force that usually receives sacrifices, we must also consider certain metal and leather bracelets, finger rings, leather pouches (saba) with curative or protective contents, filled leather waist bands (poala) and many other material objects as smaller shrines (bogluta). The effect of these tiita, however, is mostly based on their magical power, which is perceived as less personified.

Although many of these personal “jujus” (tiita) receive sacrifices, they are not included in the sacrificial cycle of a compound (e.g. at the harvest offerings), but sacrifices are carried out “as needed”, i.e. if the power working in the objects has to be “charged” again by sacrificial blood (endnote 6).

The forms of application

Liquid medicine taken orally

Only in rare cases are liquid medicines taken without an exactly prescribed preparation. Often an aqueous extract or preparation is made from plants in order to make use of the healing power of the inner juices of roots, bark, branches, leaves or (more rarely) fruits. The herbal parts are lightly crushed in a mortar a few days before use and placed in a clay pot with clear water, or they are boiled in water on the day of use. The watery solution is “funneled” (Buli tugli) into small children’s mouths or given to them in a very small calabash bowl after the daily bath but before breastfeeding (endnote 7). Adolescents or adults drink it before or after eating. The duration of treatment depends on the local customs, on the instructions of a medicine man (native doctor, tiim-nyono) or a diviner (endnote 8).

Charring and the inhalation of steam or smoke

Particularly if the ingestion of a medicine is part of a certain ritual sequence, charring (kabika) of plants is carried out. This method can be combined with the intake of an extract or a decoction as presented in the following description.

In a house in Wiaga-Bachinsa where a set of five-year-old twins lived, a ritual called nipok-gomsika (literally: ‘preparation of a woman’) was performed in 1988 to protect the twins, their mother and the other inhabitants. Most of the root pieces of the very rare ti-nyiam tree were cooked in a bimbili pot to produce a drinkable medicine. The smaller part of the roots was put in a ngoadi sieve pot. Two toes were cut off from a live chicken and the blood dripped onto the root medicine. After these roots in the sieve pot had become embers over the open hearth fire, water was poured over them. One after the other, the twins, their mother and many other housemates approached the sieve pot, held elbows, feet and knees over the smoke or steam and inhaled it. The charred roots were later ground on a hoe blade into a black powder, mixed with shea butter, salt and pepper and then eaten by all the participants together with millet porridge.

In a vayaam ritual (see below), the charred medicine was eaten in two courses. The thick paste was eaten pure in small quantities by the two male initiates who dipped their index fingers three times into the medicine and had to lick it off (the number three is associated with the male gender, the number four with the female one). Later, the rest of the medicine was stirred into the freshly prepared millet porridge served to them (endnote 9).

The ritual of inhaling (Buli chablika) smoke has a considerable importance in the initiation of a diviner (jadok-gomsika). Here the smoke had an effect, which I observed in Wiaga-Goldem, on the consciousness of the initiand and caused the affected person to enter a trance-like state (1989).

Musa-cakes drying on a flat roof

Solid and liquid food as medicine

The preparation of food which is intended to have simultaneously a medical effect occurs quite rarely with the Bulsa. The use of kaam (potash, “local vinegar”, cf. Kröger 2010: 210) is often prescribed for the sauces/soups (jenta) given to convalescents, pregnant women and women who have recently given birth as an addition to millet porridge. Kaam itself is also very popular as a spice among healthy eaters.

As the only example for the production of a solid, cake-like medicine, I know the preparation of the red musa medicine (Sing. musiri). It helps against abdominal pain (poi domsik) and similar complaints. The medical practitioner Akanue (see below) produces it from the bark of the mahogany tree (kok, Khaya senegalensis) and the roots of the pokong tree. This medicine is also frequently used in other parts of the Bulsaland and the red balls are often seen on the flat roofs of the compounds where they are laid out to dry.

Treatment of open wounds, ulcers, rashes, etc.

Often (soaked) leaves are placed directly on the wound. Different soil types are also used, with the most important being black earth (bakta, Sing. bauk) which is procured at swampy river banks. The use of commercially available disinfectants (jodines), too, is known in many compounds and has been easily recognizable by its violet colouring.

During my teaching time at the Sandema Boarding School, many students suffered from Guinea worms (gari miisa), which mostly came out of the body at the legs. The students wrapped the escaping worm around a small stick that remained on the body at this point. From time to time they wrapped the worm further on the stick until they had taken out the whole worm. They knew that breaking the worm could lead to serious complications.

4. Medicine and rites

The radial pattern has been drawn with a piece of ordinary charcoal

A new-born baby with a piece of umbilical cord

Medical procedures are an inherent part of most Bulsa rites. Many of theses rites are a reaction to physical hazards, drastic changes or diseases and can be the beginning of a new phase in a person’s life (e.g. pregnancy, birth, death). However, physical changes can also be voluntarily performed on one person by another (e.g. incising tribal scars, umbilical incisions, female circumcisions, etc.). Supernatural powers and spirits can also force people to perform certain rites, for example through illness or accidents, and thus mark a turning point in their lives.

At birth, medical procedures and religious rites can be separated very clearly (endnote 10). Obstetrics are carried out by an experienced woman from one’s own compound or the neighbourhood. The umbilical cord is cut about 5-8 cm from the body and then tied off close to the skin with a fibre of the dawa-dawa pod (sieng or siek). The remaining part of the umbilical cord falls off by itself after about 2-3 weeks. It is often a male specialist who presses the afterbirth (koalima) out of the body by massaging the abdomen.

Among the Bulsa, tribal marks run from the root of the nose across one or both cheeks and are cut by an experienced man from the youth’s own compound or neighbourhood (endnote 11). In Anyenangdu Yeri, the landlord Anamogsi cut these scars for all the children in the compound himself. Finely ground black medicine from charred roots is rubbed into the open wounds.

While the child is lying on her mother’s legs, a woman is cutting the incisions.

Many Bulsa wear small Akan marks on their left cheek, even if they or their parents have never been in the south of Ghana. The cuts and the rubbed-in medical coal powder is applied if the child has suffered from fits or if the parents want to prevent these.

As regards umbilical scars, many of my informants argue that these incisions have a purely medical purpose. They are applied after a baby or toddler suffers permanently from abdominal pains and the parents assert that after cutting these radiating incisions their children were completely free of further pains. Others, however, told me that the sick child was tortured by a spirit that enters its body through the navel. By applying these scars the spirit will no longer recognize the child.

An elder woman of the compound takes care of circumcision wounds (FGM) and treats them according to the circumciser’s instructions by applying various medicines (endnote 12). The girls interviewed most often mentioned the following medications: leaves (mostly in roll form) of posidi (Compositae sp.), leaves of young shea trees (cham poli) or of ngaarib (Vitex cienkowskii or V. doniana), the decoction of titibi leaves (Combretum glutinasum or C. ghasalense) and black bagta mud.

Therapeutic measures accompany not only many rites, but some transition and initiation rites themselves are regarded as remedies against particularly severe and persistent diseases. This also means that a disease may be the trigger for performing these rites. Above all, mental or psychological disorders are almost never cured by a tiim-nyono‘s medication alone but by ritual actions.

If an ailment affects an infant over a longer period of time, and traditional or modern medicine prove to be ineffective, a visit to the diviner will be necessary. There, after spreading all his divinatory

A black medicine has been rubbed into the wounds.

symbolic objects on the ground, the diviner will use his staff,, to point, for example, to a chicken’s breast bone, which means an ancestor, an earth spirit or another divine agency “demands the child for himself” (…lueri biika ate badek). In such a case, all other medicines are useless. The dedication of the child to this spirit (segi), which henceforth has a kind of protective function, is carried out in the segrika ritual. Since the child is also given a name on this occasion, the ritual is (perhaps not quite correctly) also called “naming ritual” in English (endnote 13).

The segrika-tiim vessel, positioned next an ancestor shrine, has been filled with new ingredients

The healing effect of the segrika rites is supported by the intake of medicine, which is kept in a medicine pot (tibiik) placed directly next to the shrine of the “protective spirit” (segi). This pot receives part of the sacrificial food in each offering to the main shrine. The medicine which is administered to the child daily – after each bath in the case of small children – almost always consists of plant extracts diluted in water, e.g. from:

roots of the shea butter tree (Butyrospermium parkii, Buli: cham)

roots of a gaab tree (Diospyros mespiliformis) that never bears fruit

roots of the kankpiiling shrub (=kampuulung? Sterculia setigera?)

roots of the waaung-soluk tree (Annona senegalensis)

parts of cham-bakurik, a parasitic creeper often found growing on shea trees

bark of the kapok tree (Ceiba pentandra, Buli: gong)

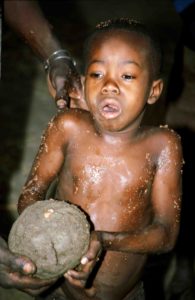

A small boy is carrying his new wen-shrine from the footpath to his mother’s courtyard, where it will be placed permanently. The wen-stone in the middle of the mud ball is visible. The boy’s body has been rubbed with the residues of the millet beer production.

If the disease does not improve after the segrika or if other symptoms appear later, another ritual called wen-piirika becomes necessary. In this ritual the wen of the affected person is given a personal shrine in a small, stationary mud ball about 10 cm high which, from then on, regularly receives sacrifices from its owner. The wen is a fate-determining divine power and an important component of the human personality that exists outside the body (endnote 14).

The wen‘s desire for further sacrifices or gifts, such as bracelets, cowry jewelry, a red cap, etc., is indicated again by the wen through diseases or accidents befalling its human owner.

In the 13 wen-piirika rituals which I was able to participate in between 1973 and 2008 as well as in many other detailed descriptions given by informants, it was almost always diseases or mental disorders that precipitated and caused the performance of a wen-piirika. In one case the quarrelsomeness of a married woman was the cause, in another case an approximately nine-year-old boy had shot at chickens and humans with his catapult (maauk), and in another case a shepherd boy hit a goat which had wandered into a millet field so violently that it died. Perhaps the latter cases were also attributed to mental confusion. It is remarkable that in the last three cases, moral misconduct is seen as a measure carried out by supernatural beings in order to spur a performance of the ritual and thus absolving the culpable persons from any moral guilt. A man who was always healthy in his youth and never showed any abnormal behaviour is usually pitied by all, for his wen is so weak that it cannot enforce its desire for worship in a shrine. If the physically and mentally healthy person dies without a wen-shrine having been erected, he cannot be venerated later as an ancestor.

A disease that requires ritual measures may also be caused by the affected person, e.g. if a man, kills a wild animal in which a bush spirit (jadok) was embodied or if a man or woman sees such animals with supposed supernatural characteristics (often chameleons) mating. Immediately after this event, the person will become ill or mentally disturbed. Healing again is only possible under the guidance of a diviner who may instruct the affected person to build a clay shrine with a relief image of the respective bush animal and to perform sacrifices to it henceforward. In particularly severe cases, the bush spirit (jadok) can even force the person to become a diviner himself. During the initiation (jadok-gobika), different medicines are used again. In this case their purpose is not so much to cure a disease but to bring the novice into a trance-like or completely unconscious state of mind. At a diviner’s initiation in which I could participate in Wiaga-Goldem, the black medicine was made from the following ingredients:

• three kantimiiri fruit (see photo in the chapter “List of Plants…” (BULUK 12)

• a piece of skin of an electric fish (ninigimi, Malapterurus electricus)

• a small bundle containing the parasitic creeper yauk-nyok

• some tubers of the yiilo climbing (?) plant (photo: ibd.)

• roots that have grown into a riverbed (without regard to the tree species)

• some nya-miisa (unidentified spider-like insects living and running on the water)

All the ingredients were charred over a fire. The initiand had to inhale the smoke and then eat the ground medicine mixed with salt, pepper and shea butter. He was carried half unconscious into the kusung-dok (a roofed shelter) and thus left the ritual scene until the next morning.

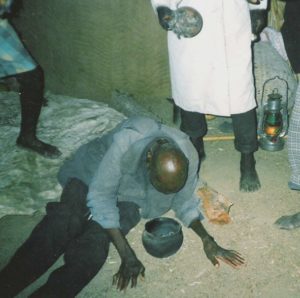

The novice is inhaling the smoke which sets him in a trance-like state

5. The healer (tiim-nyono)

A guinea-fowl is sacrificed to a tiim-nyono’s medicine under the ceiling.

Almost all Bulsa, with the exception of those who are completely alienated from their own culture, have some knowledge about the traditional use of plants for medicinal purposes. Many diseases are treated without visiting a healing specialist. Although the latter exists under the name tiim-nyono (pl. tiim-nyam, literally ‘owner of medicine’, medicine man, native doctor, herbalist) or the near-synonym tebroa (pl. tebroaba, ‘healer’), these names are by no means only used for fully specialized healers. Anyone who possesses a kind of medicine, knows about its use and makes it available to those in need can be called tiim-nyono. Thus, under this name there are different degrees of specialization. Some healers have good knowledge of magical applications while others are knowledgeable of practical treatment, e.g. after accidents. The Bulsa do not distinguish any subcategories concerning the healing activity of a tiim-nyono in Buli. A specialist for bone fractures and even a doctor with a medical university degree may sometimes be referred to as tiim-nyono, although the English word “doctor” [‘dɔ:tə] is mostly used for the latter.

Here, however, for reasons of a structured presentation, three main areas of activity are distinguished.

• As I could find it in Wiaga-Badomsa, many compounds have an esoteric knowledge of one or two medicinal plants which was acquired by a certain ancestor, the original tiim-nyono. Whether the ancestor discovered the healing power of a plant himself or whether he bought it could not be determined in every case.

Asik Yeri, a compound in Wiaga-Badomsa, has a certain monopoly on the distribution of the yiilo fruit plucked from a shrub near the compound. These are used together with other ingredients for medicine during the initiation of a diviner.

People come to Anyenangdu Yeri from afar to buy medicine from the branches of the kangbegi tree (soap berry tree, Balanites aegyptiaca). It is supposed to help patients who can no longer eat and drink (because of an esophageal occlusion?). The soap berry tree also grows in other parts of Bulsaland, and anyone could get some branches there. The decisive factor for its effectiveness, however, lies in its acquisition through an ancestor (Aluechari). Purchasers place the medicine and their two chickens on the shrine as a form of remuneration. Moreover, an exact instruction of the seller about the application of this medicine is a prerequisite for the effectiveness of the medicine.

• Other medicine owners are visited because they are known to have collected a large number of medicines and know about their use. Often these are medicinal plants that are difficult to find in the bush, and perhaps it is no coincidence that some of the medicine men I know are also famous hunters.

The diviner, tiim-nyono and hunter Ayomo Ayuali, for example, keeps a plastic bag in his bedroom in which, neatly wrapped in paper and plastic foil, there are about 20 remedies for various diseases. He sells the medicine to those seeking help and gives them instructions which mostly concern “medical” advice more than magical practices. Rarely does he medicate the body of his visitor himseelf. Often the sick person does not even appear himself. Rather, a father appears and asks for medicine for his sick son so that part of the prognosis was already made by the father before his visit.

Akannue’s medicine under the roof of his kusung

• Other tiim-nyam (pl.) are characterized by their great medical expertise and their practical dexterity in dealing with the sick and injured. Akannue Anganchaab from Wiaga-Yisobsa is known and coveted far beyond the borders of Wiaga. He assured me that he did not possess any magical medicines. His decision to do more medical work in addition to his agricultural occupation only developed in him when he recognized his talent and ability in this profession.

Today, his healing activity is related to almost all diseases occurring in Bulsaland, only eye diseases and leprosy are not treated by him, although he also knows therapies for simple cases. He is often called upon in emergencies where less experienced medicine men are unable to help.

The following list shows further diseases and emergencies where Akannue can help:

• He treats abdominal pain (poi domsik) with the red musiri (pl. musa) medicine (see above).

• A cystitis (bladder infection, sinsam liuuk) is treated with the extract from the roots of the zeglik (Acacia sp.) and dambuuring tree (Gardenia erubescens or Gardenia ternifolia, cape jasmine?).

• If a patient has blood in his urine (sinsam-bulik), Akannue looks for the roots of a crippled titibi-shrub (Combretum glutinosum or C. ghaselense) and prepares a decoction for his patient to be drunk.

• He treats blood in the stool with a decoction of waaung-soluk roots (Annona senegalensis).

• For stomach pains, especially with babies, he applies a medicine obtained from parts of the kpikpali-galik tree (kpikpalik = Afzelia africana?).

• A green juice, which Akannue keeps in a plastic bottle, helps against ear pain.

• If the patient feels dizzy (giling-giling), Akannue either lets him chew the hard grains of the red giling-giling-poning millet, or he grinds them and the patient drinks the flour mixed with water.

• If a patient suffers from constipation (poi-geruk), Akannue gives him an extract of the roots of the popagalik tree in a chin-tuin calabash. The inside of such a calabash bowl is not completely scraped out during its production and drinks drunk from it have a bitter taste.

• To treat diarrhoea (chaaruk), the patient drinks the extract from the roots of the pogi- (Terminalia avicenioides) and kok-nang-muning tree (kok = Khaya senegalensis).

• The decoction from the roots of the dambuuring and mung tree (Acacia sp., red variation of the zaan-piak acacia) is drunk to control coughing. In addition, some roots of the above-mentioned trees are charred and the patient has to inhale the smoke. Then Akannue grinds the charred pieces and mixes them with pepper and shea butter before the patient ingests them.

• Akannue distinguishes different types of fainting (cha). If it happens unexpectedly, he injects water into the patient’s nose until he breathes again. After an accident (e.g. falling from a roof, which can be caused by the ngmienta disease), Akannue burns the dried, very small bush plant nanggbangka wuruk (nanggbang = pidgeon) and rubs the ash, together with oil, on the body.

• Worms in the stool are treated with an extract of the taarik plant (= taaruk? Mitragynis inermis?). Akannue spreads the juice of kantain on the parts of the body infected by guinea worms (gari miisa). Following this treatment, the worm comes out without pulling it.

• For the treatment of light spots on the skin (solimbaata), which are probably caused by an infestation of ring worm, the liquid filtrate of millet ash is boiled and the light residue (kaam) is applied to the affected spot.

• Nosebleeding: A piece of millet porridge (saab) is placed on a hearth stone (daan-tain) and a male patient has to pick part of it up with his mouth and eat it. This has to be done four times by a female patient and three times by a man.

• After the bite of a snake (waab), the roots of waaung-duob (literally ‘monkey’s dawa-dawa tree’) are soaked in water. The resulting bitter liquid is applied to the open wound which is then beaten with a donkey’s tail.

• After a scorpion bite (nuoong = scorpion), the wound is cut open and the charred and ground up roots of the shea butter tree (cham, Butyrospermum parkii) are applied.

Akannue is making a chiwaasa splint.

The effectiveness of Akannue’s remedies is still unverified scientifically. Experience shows, however, that they have helped many patients. Even if Akannue claims that all of his healing methods are completely free of magical elements, some treatments are still associated with traditional magical ideas. One example would be when an action has to be performed four times by female patients and three times by male patients.

Akannue is considered an expert on bone fractures and sprains, but he is also frequently called in during difficult births or when the placenta is stuck. His therapies do not differ fundamentally from those of European doctors, despite his relatively simple means. According to his information, the most common course of action when setting broken bones is to make sure that the two fractures are placed correctly in front of each other and can grow together without disturbance. If bones have grown together badly or crookedly, he re-sets the break again. Akanue himself weaves small mats from the thin but strong sticks of the chiwaasa tree (Waltheria indica) to use as splints. Such a “mat splint” (chiwaasa, pl. form of chiwiak) is wrapped around the patient’s broken leg or arm. Moreover, Akannue uses corrugated cardboard and linen bandages for this purpose.

While there are some other specialists for broken bones and difficult births in Wiaga, Akannue is the only one who can manually remove a stuck placenta from the woman’s birthing canal. He uses the same method as that used in Navrongo hospital, which is more than 40 km away.

Since Akannue, as frequent interruptions in my interviews have proved, is constantly called upon for help, he considers it appropriate to carry the following medication with him at all times, even when shopping at the market:

• medicine for arm fractures

• medicine for sprained hands, feet and the neck

• medicine for the treatment of pregnant women

• medicine for difficult births

According to him, he does not demand any money for his activities but is paid voluntarily. It seems, however, that a fixed tariff has nevertheless developed. For removing a placenta, he receives e.g. 800 Cedis, 1 chicken and ½ to 1 bottle palm-brandy (akpeteshi).

A boy’s broken arm was splinted with a chiwaasa-mat.

6. The most important independent medicine shrines

Fly-whisks

As already noted, Bulsa do not make a sharp distinction between magical and religious actions and attitudes because the magically efficient remedies are more or less integrated into religious performances. As examples for this integration, sacrifices to medicine shrines will be examined here since, for a “pseudo-scientific” magical application of medicine in the sense of Frazer (see above), sacrifices would not be necessary. In the following examples, some medical practises concerning whether and to what extent their effectiveness is shaped by sacrifices will be dealt with.

• A large part of the medical applications of medicine takes place without sacrifices and an integration into religious acts. These remedies not only include modern tablets and medicines, which are prescribed in a modern clinic, but also traditional remedies whose knowledge is handed down in the Bulsa families. Furthermore, the medicines prescribed by the tiim-nyono Akannue (see above) belong to this group.

Some material objects such as a fly whisk (juik), consisting of an animal tail and a leather handle and used for scaring away flies, can be purely secular. If, however, there are effective medicines in the handle, it will receive sacrifices.

• Very often a remedy (tiim) or an amulet (tiim) is not a shrine on its own, but the magically-working tiim receives offerings together with sacrifices to the shrine of the ancestral acquirer. The remedies or amulets can be put, for example, on the clay base of the shrine. After a chicken has been killed over the sacrificial stone (tintankori) of the main shrine, some drops of blood are allowed to flow on the amulet or on the medicine pot standing beside it.

• Some magically-working material objects are worshipped in an independent shrine. If, for example, all shrines of a compound (yeri) receive a sacrifice after the millet harvest, the medicine shrines are arranged to receive their sacrifices following the more important sacrifices made to the ancestors, ancestresses and earth shrines.

Only a few important and widespread independent medicine shrines of the Bulsa will be described below.

The nipok-tiim (“woman’s medicine”)

Sacrifice to a nipok-tiim

In many compounds this medicine-shrine consists of one or two clay pots of different sizes containing liquid medicine to prevent wives from running away. Depending on the diviner’s instructions or local traditions, it may contain water and the roots of the waaung-soluk (Annona senegalensis) or another tree. It may even contain pieces of reddish brown mica, as I found them in one compound.

The nipok-tiim seems to be very common, at least in Wiaga, for almost all compounds in Badomsa that I know had such a shrine.

In Sandema this shrine seems to be little known, while among the Koma there are several shrines with similar functions. The daataala-gbieng (daataang, ‘enemy’, gbieng, ‘shrine’) is directed against all “the husband’s male rivals, especially so, when he has managed to marry another person’s wife. Then the medicine serves as an antidote against medicine of rivals who still want to entice his wife away” (Kröger 2010: 196). “To ensure that his new wife stays permanently in his house he mixes a little of the medicine into his wife’s food (ibd. p. 199).

A nipok-tiim shrine after a sacrifice

In Wiaga I also received information that other shrines, for example the Tallensi shrine Tongnaab or Anamogsi’s biam tiim (see below), may take over the functions of “woman’s medicine”.

The nipok-tiim is mainly used at weddings shortly after the new bride has been taken to her groom’s compound. In Badomsa I was able to participate in the rituals for one of my newly-wed co-workers and his wife.

The bride, who had usually lived in the centre of Wiaga, had to spend the previous night in the traditional compound in Badomsa. During the ritual she wore a fibre apron over her clothes. She had to do the work (such as fetching fresh water) herself in preparation for the sacrifices.

The sacrificer, a young man who had taken over the duties as acting head of the compound, cleaned the two big samoansa clay pots of the shrine and filled them with fresh water, tree roots and pieces of mica. First he sacrificed millet water (endnote 15) to two ancestors, probably to inform them about the forthcoming event. Then the following parts of the nipok-tiim were offered millet water and the blood of a black chicken (endnote 16):

• both tiim pots

• a small drinking calabash

• a bracelet hanging from a forked branch behind the clay vessels

• a stone under the two clay pots.

A daughter of the house is pouring medicine-water into the returning wife’s face.

The young sacrificer and the bridegroom sat directly in front of the shrine while the bride, who had to be present at all costs, had retreated into the entrance to a room located in the same courtyard. In the afternoon, millet porridge (saab) and cooked pieces of black chicken meat with a groundnut sauce were sacrificed to the shrine.

In the dark, after I had left the compound, the bride had to drink the medicinal water of the nipok-tiim and, together with her bridegroom, take a bath with the diluted medicine in the bathroom of the compound.

If a woman tries to leave her husband despite the rituals, she may be seized by epileptic fits. But there is an antidote for these as well. This is called song-tiim, and it cancels the effect of previous husbands’ nipok-tiim and eliminates all guilt regarding premarital sex.

When a woman has left her husband for a long time and later returns to him, her treatment with the nipok-tiim looks different. In 1988 a childless wife of Anamogsi’s returned to Anyenangdu Yeri. As she passed the entrance (nansiung) to the compound, Anamogsi’s daughter, Anyiini, poured medical water from the nipok-tiim into the wife’s face. This was accompanied with great laughter.

Pobsika: A young man is blowing ashes with his wife.

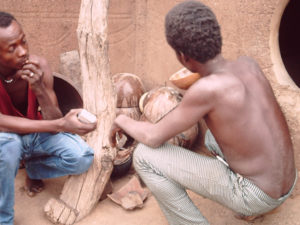

Grinding the charred medicine in a potsherd

Under the name nipok-tiim, there are also shrines with a different function. In Anyenangdu Yeri, for example, a shrine called nipok-tiim, nipong-tiim, biaroaba-tiim (biaroaba = mother in childbed) or pobsika-tiim can be found in the dalong (endnote 17).

The clay pot contains uncharred pieces of the kuruk plant, which lives as a parasite on other trees, mostly baobabs. Only shortly before its use following the ritual called pobsika (blowing ashes) does the head of the compound, Anamogsi, char the quantity needed for the ritual. According to my enquiries, this nipong-tiim medicine is only used after a pobsika ritual. For a newborn and its mother, there are usually sight taboos, which can refer to the father of the newborn, to the father of the spouse (i.e. the baby’s grandfather) or to the next oldest brothers or sisters of the baby. Before they are allowed to see the new mother and the baby, they must blow (pobsi) white stove ashes towards the mother’s face while both actors have their eyes closed. In Anyenangdu Yeri, this taboo (only?) exists between the medicine and the woman who has recently given birth so that the ritual of blowing ash (pobsika) can be performed by any male person.

Drawing a black cross at the entrance of the couryard

After blowing ashes, the performer takes the charred medicine, grinds it in a pot shard and mixes it with shea butter (endnote 18). He then smears this ointment in the form of small crosses on both hands, both feet and the forehead of the mother and the baby.

Thereafter he draws small, equal-sided crosses with one finger on the following places of the mother’s inner courtyard:

• above the outer and inner lintel of the room in which the mother lives with the baby

• next to the entrance to the woman’s courtyard: outside and inside

• above the outer entrance of the woman’s grinding room (nanzuk)

They may also mark other parts of the building (e.g. a staircase) with crosses.

A black cross itself is called num-toari (evil eye) in Buli, i.e. they want to avert damage by people who are jealous of the new mother and baby after a successful birth. During my questioning, my informants always mentioned the power of the medicine to protect this part of the compound from ghosts (kokta).

Anamogsi’s sons also perform the pobsika ritual in other compounds of Badomsa which do not possess this biaroaba medicine.

The vayaam medicine of the gravediggers

A vayaam-shrine with a hoe-blade

Ansoateng’s vayaam medicine pot with an open lid

The vayaam medicine (pl. vayaasa) is often referred to as the gravedigger’s medicine. However, as numerous observations prove, it is also used by other people, under the tutelage of a gravedigger, for different purposes. For example, it is needed to ward off ghosts (kokta) and witches (sakpaksa).

Ansoateng (Atuiri Yeri, Badomsa) gave me a detailed report about his work as a gravedigger (vayiak, pl. vayaasa) and his handling of the vayaam medicine, which will be presented here in an abridged form.

He experienced himself how dangerous it is to touch and bury dead people without the use of medicine when many people died in Badomsa around 1970. Among the dead were also those from his own house. As the local gravediggers were not prepared to bury them all, to the indignation of the entire section, Ansoateng helped burying them. Then he himself became very ill for a long time; he had aching limbs and his face and body were swollen. The reason for this was that he had buried people without using vayaam medicine.

Thereafter, he acquired this medicine during his initiation as a gravedigger and henceforth he has kept the vayaam medicine in a clay pot on the rubbish heap (tampoi) in front of his compound. He keeps other remedies and supplies in his bedroom inside the compound.

In the clay pot on the tampoi there are usually four types of vayaam medicine, all made from tree roots:

1. from the roots of the kpagluk tree in a crocodile cave on a river. This is the strongest medicine. In order to cut the desired root pieces, the gravedigger has to crawl into the crocodile’s cave and then close it with thorns to protect himself from the possibility of the returning crocodile.

2. from the intersecting roots of the very rare yik tree

3. from the roots of a gaab tree (Diospyros mespiliformis) that never bears fruit

4. from the roots of the waaung-duob-pok tree (waaung-duob: Prosopis africana?)

These medicines, in combination with others that are inside the compound, are used for the following death cases:

1. for lepers (Burial without these medicines will be disastrous.)

2. for a pregnant woman

3. for a sakpak (witch, sorcerer)

4. for a sakpak-yiik (worse kind of sorcerer)

5. for a deceased person whose death occurred more than two days ago (i.e. with the onset of decay)

6. for the dead who are still walking around as kokta. Here the dundum medicine, a coarse, red-brown, edible sand, is applied additionally.

Even before an official announcement of death, Ansoateng can recognize that someone has died by observing various omens. For example, he may have had a very restless night. The next morning he goes to his vayaam medicine at the rubbish heap. When the lid (a kpalabik bowl) of the medicine pot sits diagonally, he knows that someone has died. Then he refills the pot

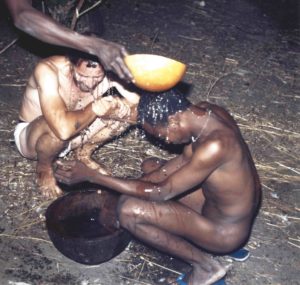

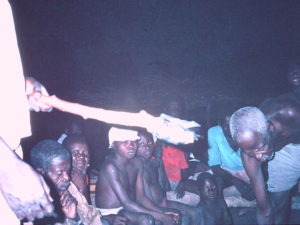

Two grave-diggers of Angaung Yeri demonstrating the beating of the body with tufts of leaves and medical water

with water, dips his hand in it and rubs this medicinal water all over his body to protect himself against the dangerous piisim smell of the corpse. He does not close the pot again. After the burial he looks into the pot to see whether the root pieces (tinangsa) are lying parallel to each other. If this is the case, he can close the pot again. If at least one root is lying crosswise, there will be another burial in the near future, and he leaves the pot open.

Ansoateng’s practical work as a gravedigger is known to me through two burials. He was the only gravedigger at the interment of an infant from his neighbouring house Anyenangdu Yeri (endnote 19).

In March 1989 a leper died in Angaung Yeri (Wiaga-Mutuensa) and was buried by five gravediggers, among them Ansoateng.

In contrast to the burial of the infant, the heads of all the gravediggers were shaved. As protection against the dangers associated with the interment of a leper, the vayaam medicine of Angaung Yeri on the rubbish dump (tampoi) received the sacrifices of a chicken and a sheep. In the dark, all undressed gravediggers took a bath with the vayaam liquid.

As I was told in other compounds, the vayaam medicine also helps non-gravediggers against other dangers and diseases, for example against swollen limbs caused by inhaling piisim , or nausea after eating spoiled food. It also prevents an encounter with ghosts (kokta). For this purpose, charred pieces of the vayaam roots are grated and mixed with fat which results in a black ointment. With this, black crosses are drawn at many places (e.g. walls, entrances) of the compound in order to repel ghosts who hate the smell of vayaam.

A fowl is sacrificed to the big vayaam vessel on the fire

I could collect detailed oral information about practical performances of the vayaam-rites. I was, however, only able to observe and physically experience for myself one single ritual sequence with several baths.

When, in 1988 after the death of an infant in my residential compound, I was asked to confirm the death of the child by feeling for her pulse, listening to her heart, etc., I was told that these touches could be dangerous for me. In Wiaga-Chiok (Anduensa Yeri), Adaapiim, a gravedigger, head of the compound and the father of my temporary assistant, Adama, offered to perform vayaam rituals and baths on me and my permanent assistant, Danlardy. Initially, he explained to me that there were different types of vayaam rituals: a simpler way, as it was to be performed on me would serve as protection against ghosts (kokta) and allow safe handling of corpses.

In order to be able to bury corpses under difficult conditions (for example after the onset of decay), a more complicated ritual and increased sacrificial activities are required. When Adaapiim was initiated as a fully qualified gravedigger, he had to provide one sheep, one goat, six chickens, five guinea fowls, salt and sheabutter for sacrificial purposes.

In Chiok (1989) I was asked to provide the following things:

• 1 white chicken (kpiak) – A small brown chicken was provided by the compound.

• 1 new hoe blade (kui)

• salt (yesa)

• millet (zaa)

• 1 glass of shea butter (kpaam)

• 1 billy goat (bu-duk), the penis and testicles of which were used for the medicine (endnote 20)

Danlardy Leander and Franz Kröger at the vayaam-ritual

Adaapiim had already provided 13 different roots for the upcoming rites. On April 1st, 1989, water in a large samoaning pot was heated on a three stone stove (daaning) in front of the compound. The hoe blade was placed on the upper opening of the vessel. Adaapiim fetched his vayaam-boguk, a closed calabash with charred medicine, from inside the compound and placed it next to the fire. He sacrificed millet water, the white chicken and the brown chicken to it and the hoe blade. After both the sacrificer and I had delivered speeches (prayers), the billy-goat was slaughtered over a small empty bimbili clay pot, and the two sacrificial spots were wetted with its blood. A young gravedigger took two different charred roots from the vayaam pot, crushed and ground some pieces of them on the hoe blade and added some salt.

Then Danlardy and I were led to the bathing place behind the rubbish heap (tampoi) where two younger, undressed gravediggers had already taken a bath. We had been told before that boiling hot water would be poured over our backs. But if we had come here without evil intent, we would have nothing to fear. While we were squatting, the boiling water was really poured over our backs. Looking back, however, I noticed that cold water was poured out of another vessel at the same time. After the water was poured over us, a helper with a leaf branch hit me quite firmly on my legs and head and then struck my back gently with this branch.

Afterwards we were led to the black, powdered medicine, which had been mixed in the meantime with shea butter (kpaam) on the hoe blade. We had to dip our fingers into the medicine three times (3 = male principle) and then lick it off. This medicine may only be taken by adults who have received their bath at the tampoi before.

Millet porridge at the stirring rod

Meanwhile, between the kusung and tampoi, some men had made “men’s millet porridge” (sa-gaang) from millet flour and water without a fermentation process. An unpeeled branch served as a stirring rod. An undressed man took this rod with millet porridge at its lower end and coated it with shea oil. Adaapiim sacrificed clear water (endnote 21), millet porridge from the clay pot, millet porridge from the stirring rod, a soup prepared from the goat’s blood, two kinds of meat and clear water again to the liquid medicine shrine on the fire and to the vayaam shrine of the compound close to the fire. Danlardy and I each received a chicken wing, a chicken leg and a front leg of the goat to be taken home. Near the kusung-dok we were served millet porridge which had been mixed with the black medicine before. Meanwhile, two women and Adama’s little son bathed in the medicinal water at the tampoi. Adaapiim called us into the kusung, where Danlardy and I were offered a calabash with the reddish, hot medicine water (from the samoaning on the fire). The old man told us not to be afraid of ghosts (kokta) anymore but also that we should not tell anyone if we saw one.

Danlardy and I had to take more baths at the tampoi over the following two days. On the second day (April 2nd, 1989), two of Danlardy’s mothers accompanied us. They also wanted a bath with the medicine because they often had to touch dead people. As women they had to take the baths on four consecutive days. They each brought a guinea fowl (kpong), which was sacrificed to the two shrines. Men’s millet porridge (sa-gaang) was also prepared for them, but millet porridge with medicine from the stirring stick was not sacrificed to the two shrines. For Danlardy and me, the rituals had been simplified on the second day. At the tampoi we had lukewarm water poured over us and had to drink the liquid medicine three times afterwards without eating millet porridge with black

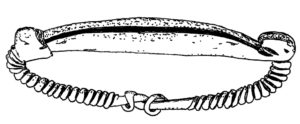

Bang-yoluk iron bangle

medicine. On the third day, we could wash ourselves with the medicine water in daylight.

Finally, Adaapiim gave us medicine, and we were instructed to always keep it in our house and not to allow anyone else to eat it. I was ordered to grind the charred medicine with a stone on a hoe blade and eat it mixed with salt and oil.

Vayaam medicine can also be worn permanently on the owner’s body. Although this rarely occurs today, Bulsa blacksmiths traditionally make iron arm rings with a tubular middle part (bang-yoluk). In this part, very small particles of medicine can be stored. An open slit (yoluk) allows the medicine to work unhindered (Kröger 2001: 475).

The peintiik shrine

The owners and sacrificers to the peintiik shrine are supposed to become invulnerable in every fighting conflict. A close relative of the owner and sacrificer of such a shrine told me that he suffered severe wounds in World War II despite having sacrificed to the shrine before. However, as he assured me, without the peintiik medicine he would certainly have died of his wounds.

While the shrine certainly had a greater significance in the pre-colonial period, in which numerous conflicts were carried out in feuds, today we usually find at most no more than one peintiik shrine in the lineage corresponding to a sub-section. Of the five subsections of Wiaga-Sinyansa, only Bachinsa, Badomsa (Abapik Yeri) and Kubelinsa possess such a shrine. As an explanation for its rare occurrence, an informant from Badomsa told me that the handling of this shrine was very dangerous and, if mistakenly handled, could lead to blindness.

I myself could only participate in a single peintiik sacrifice in Abukuri Yeri (Sandema-Kalijiisa-Yongsa). Already days before our invitation to the sacrifice, various ingredients for the medicine in a ceramic pot had to be acquired, namely:

The peintiik shrine with the baobab shell in the vessel, the millet cobs (right) and the namarik quiver (in front)

1.+ 2. branch-pieces of a dueb/duob tree (Parkia biglobosa) and a gong tree (Ceiba pentandra). Both trees should be standing close to each other and the branches of one tree should penetrate those of the other.

3. roots growing under crossroads

4. some za-piela millet cobs (see photo)

5. one hot pepper pod

6. some arrowheads (there were already about 100 of them in the pot)

7. a gbaluk spearhead

8. three root pieces from the kampuulung tree (Sterculia setigera?)

9. three root pieces from the cham tree (Butyrospermium parkii)

10. roots of the ga-duok tree (literally male gaab tree, i.e. the tree should not bear any fruit; gaab = Diospyros mespiliformis)

11. roots of a titibi-namelung shrub (titibi = Combretum glutinosum?)

12. roots of the titibi gammi shrub

13. branch pieces of the mumulik tree (Lampyris sp.?)

14. leaves of the pok/pogi tree (Terminalia avicenioides?)

15. roots of a cham (see above) and pokong tree (= ?) growing side by side,

16. three stones (male principle!) from the “monkey rock”, the male Adogluk tanggbain,

17. four pieces (female principle) of bark from a voong/vuoom tree (Bombax costatum?) growing on the female Ayiisieng tanggbain

17. a stone from the top of a rock column

19. a bunch of white feathers

On the sacrificial day, the ingredients were already in the ceramic medicine pot as well as about 100 arrowheads from earlier sacrifices. The shell of a baobab fruit which was used as a drinking bowl (see photo) floated on the surface of the liquid medicine.

My German companion, Stefan Völker, and I had to deposit all of the money that we had on us before the beginning of the rituals. Atefelik the sacrificer (see photo) explained to us that strangers, except whites, must not touch the arrows. He himself was not allowed to have sexual intercourse on the night before the sacrifice.

Besides me and my companion, the landlords of two neighbouring compounds which, together with Abukuri Yeri, form a foreign lineage within Yongsa ,had come to the sacrifice.

Before opening the pot, the sacrificer knocked three times on it, took a white tuft of feathers and placed it on a hoe blade next to the pot. During all the phases of the sacrifice, a leather arm quiver (namarik) leaned against the pot. The following sacrifices were offered to the medicine:

1. a cock donated by me

2. a chicken donated by my companion, Stefan

3. a chicken donated by the head of the compound

Sacrificing to the peintiik shrine

The blood of the animals flowed only on the lid of the pot, not inside. After the chickens had been cooked and millet porridge (saab) had been prepared, the second part of the sacrificial acts took place at 12 o’clock with the following sacrifices:

1. millet water (It must be made of za-piela or white millet; zamonta or reddish millet is unacceptable).

2. clear water for the shrine “to wash its hands” before receiving porridge

3. millet porridge. The millet flour for it was prepared with water in which baobab fruits had been boiled. Thus the porridge had taken on a greenish colour.

4. – 6. pieces of meat and parts of the liver from the three sacrificed chickens

Then the sacrificial meal, which consisted of millet porridge with “light soup” and the remaining chicken meat, was served.

Before leaving, Atefelik told us that we were not allowed to tell women about our information and observations, because they can marry into other compounds and then reveal the secrets.

The biam-tiim (birth-medicine)

The biam-tiim shrine

Only one compound in Wiaga-Sinyangsa [Anyenangdu Yeri] has a traditional medicine

called biam tiim (birth medicine) which is responsible for all difficult or problematic births of babies, e.g. if the they are incarnated by malevolent bush spirits (kikita, singular kikiruk) or if twins have been delivered. It has a catchment area covering at least the whole of Wiaga-Sinyangsa. I myself [F.K.] was able to observe and document its application after a birth in the following subsections of Sinyangsa: Sichaasa (1988 and 1997), Bachinsa (1988), Badomsa (many times). Theoretically, the whole Bulsaland and even neighbouring countries could take advantage of it.

The medicine is located in the main courtyard (Ama-dok) about 1-2 m from the entrance of the dalong (ancestral room) on a mud banquet. It is kept in a clay pot and consists of root pieces of the following trees (most of which could not be identified):

tiniensidi (=dung-niesidi)

nying nyong (= piok)

beli-cham (Manilkaroa multinervis?)

Only in 1994 did I see a branched root which was called tiili (ladder) behind the medicine pot [see photo]. The auxiliary spirits (kurikparisa) of the medicine should be able to climb up and down this ladder.

A fly whisk (jiuk) and an unused, closed and twisted iron wrist ring with three loops or knots (gbingsa) had been applied to this root (which, in other years, had been only a forked branch). The ring should be used only in the case of a particularly severe case of birth. Thereafter it must be replaced immediately by another new ring. Before the application of the medicine it is laid on the medicine pot together with another bracelet. Six more iron rings and a copper ring that had been used before were lying next to the pot in 1997. The medicine owner (tiim nyono) buys the rings using the proceeds from animals supplied by customers.

Next to the medicine pot there is an animal skull as well as two lower jaw bones from animals sacrificed in the past. One of these bones is wrapped with a rope which served as a leash of the animal before the sacrifice. The shrine should receive dog sacrifices at least once a year. If no dog is available, it can be replaced by a goat or a sheep. Sometimes, next to the medicine pot, there is a supply of about twenty root pieces about 30-50 cm long.

Punching holes in the lid of the vessel

The birth medicine was acquired by Afarima, the compound head’s father’s father’s father’s wife. One day Afarima left her husband’s compound to visit her parents in Doninga. When she had not come back after some time, her husband wanted to inquire about her condition in Doninga. He was told that she had never arrived there. Even a comprehensive search in the bush land was not successful. Then she suddenly reappeared with the medicine. While crossing the “Doning River” near Doninga, she was caught by its current and only after a long time did the river release her again. Before that, the river had given her the biam-tiim, which has since had its place in Anyenangdu Yeri. The name Afarima is mentioned with every usage of this medicine. Sometimes the medicine is even called Afarima.

Agoabey described the possible applications of biam-tiim in 2019:

“The roots are put into the pot with fresh water. They set it on the fire of a three-stone hearth in the middle of the dabiak (courtyard). Then a fowl is slaughtered and a little of the blood is added to the medicine for it to boil. The boiled water can now be used to drink or bathe. During a delivery in which either the child or the placenta is not coming out, the water is given to the woman to drink, and the placenta will come out easily.

The roots that have been boiled for some time are dried, charred and ground into powder which can be mixed with a small amount of shea butter. A red-hot charcoal is placed on it to produce smoke which anybody can inhale as a form of treatment against body pains.

In difficult births or when the placenta does not come out, it is of great importance that, before taking the medicine, the woman confesses transgressions before her pregnancy (adultery, for example)”.

Biam-tiim has a special significance in the treatment of kikita, i.e. human beings possessed by a bush spirit (kikiruk, sing.). Such babies can be recognized by certain physical characteristics (endnote 22). Furthermore, twins with or without the typical characteristics are associated with such spirits and must be treated with the biam-tiim. The situation becomes complicated if there are other signs indicating that both or one of the twins is a kikiruk. I [F.K.] experienced such a case in 1988. All data of the following report refer to the only kikiruk burial observed by me in Wiaga-Sinyangsa on April 4th, 1989.

After a twin birth in Sichaasa, one of them refused to drink at his mother’s breast which aroused suspicion in the family. On April 17th, 1989, the child’s father (he was not the head of the compound) bought biam-tiim medicine “so that the child could take the breast”. But the baby died. The father asked the medicine owner (tiim nyono) to bury his son, but only after some doubts he agreed to bury it. As the owner of the “biam tiim” he was the only person who could carry out the burial without any disastrous consequences.

Around 9:00 p.m. three men and I moved to the Sichaasa compound as gravediggers. After short speeches in the kusung, we went to the round house (dok) where the baby was lying on some old cloths. He had a rather large head and smelled already. From a big clean calabash, one of the men sprinkled biam-tiim medicine with a brush (sie) on the child and the room. The father removed the baby’s necklace and took a black samoaning pot, in which the child was to be buried. The child was placed, with its head first, into this pot which was closed with a kpalabik bowl as a lid.

With this pot and an old hoe which had an axe blade fixed at its grip, the four of us – the gravediggers – went, along with the father, to a flat hill of gusunguri ants with a crater in the middle. It was a few hundred metres away from the compound (endnote 23). The father withdrew immediately after showing us the hill.

When the gusunguri ants (“black ants”) bite a human with their sharp, cutting mandibles, only a very tiny drop of blood emerges from the skin and the wound is not accompanied by any inflammation or itching. Here the ants would decompose the child’s body as quickly as possible and destroy it completely.

The three men dug a hole in the crater first with the hoe, then with the dachoruk (the spade at the other end of the hoe) until it was deep enough for the samoaning pot containing the baby to be buried. With the axe blade they punched holes in two sides of the ceramic pot and in the lid (see photo) so that the ants could penetrate all the easier. After they had sprinkled medical water again on the pot and the whole grave, the four of us washed our hands, feet and face with the rest of the medicinal water. The thin broom remained lying on the grave. Back in the Sichaasa compound, some speeches were held again. As an official payment, we took the following animals and objects with us: a goat, a small dark chicken, the combined hoe with spade (dachoruk), the calabash (from which they had sprinkled medicine) and, as a voluntary gift, a speckled chicken.

Two days later at about 5 p.m., the following sacrifices were offered in the main courtyard of Anyenangdu Yeri. Apart from the biam tiim also the wen-shrine of the late Anyenangdu and a small knobbed medicine-shrine received some drops of blood as sacrificial gifts.

Then the sacrificer laid the goat’s neck rope, smeared with blood, and a piece of its tail on the bloody sacrificial spot of the biam-tiim. Around 5.40 p.m. this medicine shrine received the roasted liver and some meat of the goat. Afterwards, the four gravediggers (including F.K.) and some other participants drank the watery biam-tiim from a very small calabash. The medicine was completely tasteless.

Further medicine shrines

The leprosy-shrine in Yimonsa

Theoretically, it would be possible to have a shrine for every serious illness. Moreover, there are shrines not only for diseases. In Gbedema there is said to be a shrine that causes cane strokes to be endured without pain.

Of the shrines used to treat a serious illness, only the leprosy shrine (ni-doma tibiik) of Wiaga-Yimonsa (Anankansa Yeri) should be mentioned here. It is responsible for treating leprosy as well as boils and limb pain and is closely associated with the rain shrine (ngmoruk tibiik or ngandiinta tibiik), especially since it was also acquired by the same ancestor, Anankansa. The leprosy shrine consists of a large calabash bowl whose lower half is filled with the skull bones of sacrificed animals. On top of these bones, there are root pieces, which comprise the actual medicine. Everything is covered by a large basket. Just like the rain shrine, no millet water may be sacrificed to it but rather clear water only, which is associated with the rain water. As concerns animal sacrifice, it does not accept dogs, donkeys and goats and, only very rarely, guinea fowls are offered. The sacrificed chickens should be white but may have some dark spots.

The Yimonsa rainshrine

The rain shrine (ngmoruk) has already been mentioned in another place (endnote 24). Although I have been assured several times that this shrine is a tibiik (medicine shrine), its responsibility for rain, lightning and thunder demonstrate a clear connection to the heavenly God (Naawen), making it an exception among medicine shrines. In my essay on the Earth Cult (2017), I mentioned that there are certain rivalries between the ngmoruk and the earth shrines (tanggbana), which do not exist in Yimonsa. uch a rivalry is especially apparent between the ngmoruk and the Tongnaab of the Tallensi since the Tongnaab is also responsible for rain.

Conclusion: Traditional and modern medicine

Traditional Bulsa still associate modern medicine largely with the white man, as the Buli name felik tiim (medicine of the white man) in contrast to Bulsa tiim demonstrates.

In the 1970s, I still occasionally experienced a certain distrust of modern remedies (or the White Man?). When I offered two pain killers to an elderly patient, he insisted on one of them being swallowed either by me or my companion.

Today the hospital in Sandema (with some doctors) and the clinic in Wiaga are always well attended. A certain reluctance towards these institutions is not due to mistrust but more, for example, to the higher costs of medicine (even if they are only low nominal fees) and a fear of later operations.

Akanming (Wiaga-Badomsa), a diviner who died at an advanced age in 1994, had an ambivalent relationship to modern medicine. Among his divinatory code objects was a small tablet tube. If his diviner’s staff points to it during a consultation, it means “go to the mission clinic with your disease”. Akanming believed that the whites have been medically helpful to the Bulsa. Once he expressed it in the following sentence: “Of all the people on earth, God loves Africans the most. That is why he sent them the White Man”. Then one morning he asked me, “Do you know that the Bulsa had a well-functioning medical system before the appearance of the White Man?”

Today, modern and traditional remedies coexist in many traditional households. Some patients drink the medicine prescribed by a tiim-nyono every day while also taking pharmaceutically manufactured tablets.

When a medicine peddler goes from compound to compound to sell his remedies, he often hears the question from a potential buyer: “Felik tiim?” or “Bulsa tiim?” However, there is a certain distrust of these peddlers, especially if they are not Bulsa (endnote 25).

What about the future chances of survival for traditional medicine? I believe that its use will continue declining over the next years in favour of modern medicine and that the relationship between the two types will also level off in the future. This is similar to the case today in European countries where, for example, there is a strong predominance of pharmaceutical products while a few traditional household remedies continue to play a medicinal role.

Endnotes

1 Cf. C. Arnheim 2018: 13.

A Bulsa woman making soap

2 According to an older method, soap is made from potash (kaam) and shea butter (kpaam). In a modernized method, the potash is replaced by caustic soda (cf. Kröger 2016: 45-46). Today, soap is mainly bought. Curd soap and soap powder is used to wash clothes while toilet soap is used to wash the body.

3 According to tradition, it is forbidden to dig up young tree plants in the bush and plant them near farms.

4 Small balls of ready-prepared seeds can also be bought on the market in spherical form. Before consumption, the medicine ball is dissolved in water and pressed through a sieve until the finished drink is obtained (cf. also Evans Atuick 2019). Traditional healers sometimes prescribe this product as medicine.

5 According to the diviner’s instructions or local traditions, it may be the roots of the waaung-soluk tree (Annona senegalensis) or another tree.

6 Cf. the incident of my assistant Ayarik Akumasi, who was attacked by a ghost at night and could save himself by pulling up his bangle on the arm (Kröger 1978: 144).

7 In this method of force-feeding a baby, the liquid is poured from the mother’s hand into the baby’s mouth so that the baby must swallow it. Young dogs are also fed in a similar way by pressing millet porridge (saab), for example, from the owner’s mouth into the puppy’s mouth.

8 Diviners can also concurrently act as medicine men. When they administer or prescribe medicine to a client, they do so in their role as medicine men.

9 This is not yet an initiation as a gravedigger. The two initiates, my assistant Danlardy Amoak and I, were permitted to touch corpses without any harm, and they were also protected from ghosts (kokta).

10 See also F. Kröger 1978: 46ff.

11 Cf. F. Kröger 1978: 118-124.

12 See Knudson 1994 and Kröger 1978: 198-240.

13 Segrika rituals are described in detail in : Kröger 1978: 65ff.

14 For details about the wen and wen-piirika, see Kröger 1978, p. 140-197.

15 Since the harvest offerings of the farm had not yet taken place, the millet had to be bought at the market.

16 According to information from another compound, the black colour indicates all the bride’s premarital transgressions (Buli daung, literally ‘dirt’) which are washed away by the bath.

17 In order to avoid confusion I will henceforth call this shrine only nipong tiim, biroaba tiim or pbsika tiim.

18 Although shea butter is almost always used here, it can also be another fat since it is only supposed to be a binder for the black powder. After one pobsika a performer used a small tin can of ointment – possibly Vaseline – bought on the market.

19 This activity is described in detail in my work on Death and Funerals (in preparation).

20 The skin of the testicles is needed to make a small pouch. When a vayaam owner travels, he can fill it with some liquid medicine, close the bag and use it for emergencies. This medicine is usually stored in the dalong (ancestral room). It can also be considered as a reserve container, the contents of which are used when the liquid medicine has run out.

21 Medical water is never sacrificed.

22 In Kröger 1978: 57-58, the following physical deformities are mentioned: a strange facial expression, a harelip, more or less than five fingers or toes, already existing teeth, or armpit and pubic hair present at birth.

23 In 1973 I was told that kikita were always buried in a secret place away from human settlements, often even in another village. In 2002 I was informed that harmless twins are also buried in a gusunguri ant hill.

24 See Kröger 2017: 48.

25 To my knowledge, peddling in the traditional compounds, either among the Bulsa or many other ethnic groups, has probably not yet been researched. The goods being peddled are mainly those that cannot be produced in the almost self-sufficient compounds. In Anyenangdu Yeri, traditional clothes, for example smocks (garta), were mainly bought from travelling merchants. Even warm dishes, which are consumed in southern Ghana but made locally by Bulsa women, can be offered in neighbouring compounds.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arnheim, Christine (2018): Maaka Projects in Gbedema 2017-2018. BULUK, Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society, 11: 13.

Atinbil, Dominic (2012): Water Pipelines in Wiaga. BULUK, Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society, 6: 13.

Atuick, Evans (2019): Tamarind (pusa), a neglected resource of Buluk’s development, Buluk Kaniak (Facebook Group), January 9, 2019.

Frazer, James G. (1963, 19221): The Golden Bough. A Study in Magic and Religion. Abridged Edition in One Volume. London: Macmillan & Co Ltd.

Knudson, Christiana Oware (1994): The Falling Dawadawa Tree. Female Circumcision in Developing Ghana. Højbjerk (Denmark): intervention press.

Kröger, Franz (1978): Übergangsriten im Wandel. Kindheit, Reife und Heirat bei den Bulsa in Nord-Ghana, Kulturanthropologische Studien, eds. R. Schott and G. Wiegelmann, vol. 1, Hohenschäftlarn.

Kröger, Franz (1992): Buli-English Dictionary. With an Introduction into Buli Grammar and an Index English-Buli. Münster and Hamburg: Lit Verlag .

Kröger, Franz (2001): Materielle Kultur und traditionelles Handwerk bei den Bulsa (Nordghana). Forschungen zu Sprachen und Kulturen Afrikas (ed. R. Schott), 2 vol., Münster and Hamburg: Lit Verlag.