UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Franz Kröger

ANIMALS, A BENEFIT FOR THE BULSA

Preliminary remark: In BULUK 14 (2023), the main article dealt primarily with plant foods and announced that animal food would be examined in the next issue, which is made up for here in a shorter form.

DOMESTIC ANIMALS (yeri dungsa)

Because the preparation of animal meat does not involve the same great variety as that involved in preparing plant foods (it is usually cooked as a soup ingredient, and in the case of sacrifices, it may be roasted over an open fire), the following presentation focuses on the characteristics of animals and their significance to the Bulsa.

The general terms for animals in Buli are jaab (pl. nganta) and dung (pl. dungsa). Although jaab can also refer to material things and humans, dung is not a general term for all animals. Especially in relation to sacrificial animals, dung is primarily used for mammals (e.g. cows, sheep, goats, dogs and donkeys). A chicken, for example, is not a dung. In a broader sense, however, the term can be applied to all mammals (e.g., yeri dungsa refers to domestic animals). For a society that was originally almost purely agrarian, a division into domestic animals (yeri dungsa) and wild animals (goai dungsa) was appropriate.

However, it is also possible to categorise animals according to where they live, their abilities or their physical characteristics. For example:

nyina nyono (literally: owner of teeth): carnivore (including domestic dog and cat),

ja-yirim (literally: flying thing): flying animal (including birds, flying insects, bats, etc.),

nyiam-jaab: aquatic animal (including fish, frogs, water insects, etc.),

teng-jaab: animal that lives underground,

ja-nyiili: horned animal (antelopes, buffaloes, cows, goats etc.).

Animal husbandry did not traditionally play the same central role as crop production in the Bulsa’s food supply. This was evident from the fact that the herding and care of domestic animals was left almost entirely to the children of the compound, and during the dry season, cattle graze unattended in the bush. However, this is no longer the case. In recent years, animal husbandry has become increasingly important, and the sight of actively herded livestock—even during the dry season—has become much more common especially in Sandema and its environs.

No comprehensive work has yet been published on animal husbandry. R. Schott (1973; 1973/74) has primarily emphasised the importance of domestic and wild animals in the religion of the Bulsa. F. Kröger (1987) has compared the lifestyles of cowherds and pupils. J. Aduedem, who was a shepherd himself in his youth, has described life among shepherds from an insider perspective. The names of animals can be found in F. Kröger’s Buli-English Dictionary (1992), and a small selection with illustrations is available in the Buli Language Guide (F. Kröger et al. 2020: 67–76, 86–87).

The following sections discuss the most important animals that are useful to the Bulsa as food or for other purposes.

1. Cattle (sing. naab, pl. niiga)

The term naab (pl. niiga), meaning cow, cattle or ox, can refer to both female and male cattle. Lalik (pl. lalisa) or varik (pl. varisa) refers to uncastrated male animals (bulls) and lalik-yierik (pl. lalik yierinsa) to castrated cattle, which the Bulsa use as draft animals for ploughing.

Nama bull

Zebu bull

In the dry season, cattle often graze without special supervision in the bush or, more rarely, near compounds. In the rainy season, it is the task of the cowherd boys to look after the cattle in the bush. While the boys pursue other activities in the bush during the day (e.g. hunting or playing), the cows graze unattended and often have to be sought out and caught again – with great effort – in the late afternoon. On the way home, when the cowherds take a break with their herd at the naa-vuuk (resting place with a small hut) and when driving the cattle into the cattle yard (nangkpieng) of the compounds, the boys must ensure that the animals do not eat millet from the unfenced fields (cf. Aduedem 2020).

Contract cattle-keeping by the Fulani used to be quite common. According to Robert Asekabta, (Sandema 2024), this form of co-operation has decreased a great deal more recently. The practice appears to be gaining momentum again as many cattle dealers in Sandema and other bigger towns are contracting Fulani herdsmen to help with taking care of their cattle. In many parts of Buluk (especially Fumbisi, Wiesi, Doninga and Bachongsa areas), Fulani herdsmen have become almost permanent dwellers (John Agandin). In former times, the sale of live ancestral cattle is not permitted without restrictions. Non-sacrificial killing (e.g. in times of emergency) must be authorised by all important descendants of the ancestral owner.

Cattle grazing in the bush

A Fulani family

Before consumers can enjoy beef, a live animal from a traditional compound is usually sacrificed to the shrine (bogluk) of a traditional deity. This deity receives only a relatively small portion of the meat (e.g. part of the liver or soft meat and blood). The majority is distributed according to certain rules among living persons (Kröger 2017: 62–63) who are usually themselves lineage heads and who, in turn, distribute the meat to sub-lineages, again according to certain rules. A nuclear family sometimes receives only a very small piece of beef.

Distribution according to indisputable traditional rules makes a great deal of practical sense in a society without refrigeration facilities. The owner of a cow can hardly eat all the meat, either alone or with his family, without some of it spoiling, and gifts to friends and relatives that might be made according to subjective preferences are likely to induce conflict.

Raw beef is cut into pieces and cooked before being eaten. The meat broth provides the basis for a sauce to which only spices and vegetables (e.g. ngmaana, wokta, bokta, etc.) are added. The main dish is usually millet or maize porridge (saab).

In addition to meat, cattle also provide hides, which are often processed into leather, and horns, which are used as containers for medicine or magical substances.

Castrated bulls are used as draft animals for ploughing. Bullock ploughing was practised in Buluk even before Independence (1957), when some big farmers (e.g. the Sandemnab, Abakisi Ayieta and Ayelingba from Sandema Kalijiisa) started sending bullocks to the Agricultural Station at Navrongo for training. The owner of a plough and draft animals often also ploughs other farmers’ land and thus earns welcome extra income.

2. Sheep (sing. posuk, pl. piisa)

Most of the statements about Bulsa cattle also apply to sheep. During the rainy season, sheep are typically herded by a younger group of male and (rarer) female children near the compound. The animals usually spend the night in their own sheepfold (zong).

Most of the statements about Bulsa cattle also apply to sheep. During the rainy season, sheep are typically herded by a younger group of male and (rarer) female children near the compound. The animals usually spend the night in their own sheepfold (zong).

Sheep are often owned by individuals whose families can either consume the animals themselves, sell them or give them away as presents. Their skins can be used as seat pads, or more rarely as a waist apron or to make a leather bag. However, when the flock is small or when children are unavailable, sheep may be tethered near the compound instead. This has become the predominant practice in most Bulsa towns and villages today due to school and other responsibilities (Agandin)

3. Goats (sing. buuk, pl. bue or bua)

Goats are usually not herded during the rainy season; rather, they are pegged near the compound and driven into a stable (zong) at night.

Goats are more often private property than are cattle, for example, and their owners are more likely to eat or sell them without prior sacrifice. Their milk is considered disgusting, and even children shun it. A man can make a fur apron from their skins or use these to make pouches or belts.

Ritually, goats are considered ‘black animals’ (dung sobluk, pl. dung sobsa), which means that their meat may not be consumed after some rites of passage (e.g. circumcision).

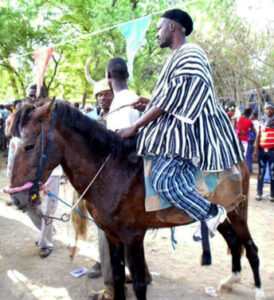

4. Donkeys (sing. boning, pl. bonisa)

A two-wheeled cart with a donkey

Donkeys are often herded together with cattle in the bush, but they can also be hitched up near a compound. They spend the night with the cattle in the interior cattle yard. In addition to their importance as a source of meat, donkeys are primarily used as draft animals in front of simple, two-wheeled wooden carts to transport, for example, stones, gravel, wood or crops. Children and young people also use them as mounts. Donkey tails are very popular as fly whisks, with or without magical contents. Danlardy Leander told me that when he sold individual parts of his slaughtered donkey, he got as much money for the tail as he did for the rest of the meat.

Donkeys can also be sacrificial animals, but some shrines (e.g. some tanggbana) disdain donkey meat.

5. Dogs (sing. biak, pl. baasa)

All Bulsa dogs are probably mixed breeds; most are medium-sized, very slim and, strikingly, many are reddish-brown in colour. They roam freely inside or outside the compound, often sleeping in an inner courtyard at night when they are not on night raids.

Dog given to a bride’s brothers

A puppy is fed (mouth to mouth)

They are particularly useful to humans as guard dogs, warning them of intruding thieves, ghosts, snakes and other dangerous animals. They kill and consume harmful animals, especially mice and rats. They also keep the compound clean by eating the stool of babies. For example, if a toddler who is not yet toilet-trained has soiled the floor of an inner courtyard, its mother can call a dog to clean it up. Before they can be used for hunting in the bush, dogs require brief instruction from their masters.

Dogs can be sacrificial animals, but I have never seen a dog sacrificed at a tanggbain or to an old ancestral shrine. In contrast, some shrines of divine spirits (e.g. juik shrines) are fond of demanding dog meat. A dog is the gift of a newlywed groom to his bride’s brothers, who are in search of their sister.

Many Bulsa consider dog meat a delicacy, and it can be bought at markets. Other ethnic groups in Northern Ghana also consume dog meat. However, ethnic groups in the South do not openly accept the consumption of dog meat; thus they tease the Bulsa and those other enthnic groups about their preference for it.

Affectionate behaviour towards a dog by its owner, even a child, was traditionally not very pronounced. However, in more recent times, this has been observed sporadically, primarily among schoolchildren (see Kröger 2011: 127–135).

6. Cats (sing. doglie or dok-biak, pl. doglieba or dok-baasa)

I know little about the introduction of cats among the Bulsa. The very few cats found in the compounds are probably mixed breeds. In my large residential compound (more than 150 inhabitants), there was only one cat, and the owner was an adult woman. Cats offer only limited benefits and, in particular, have few advantages over dogs. Cats are not a source of meat for the Bulsa, and they are not sacrificial animals; however, they catch and eat mice, lizards and snakes. Whereas dogs only draw attention to snakes by barking, cats kill them, and if they are not interrupted by humans, will also consume them.

In one case, I know from oral information that a funeral service was allegedly held for a cat (a practice that is likely to be more common for horses, but unlikely for any other animals).

7. Horses (sing. wusum, pl. wusima)

Horse-rider at Sandema Feok (photo Slim Badek)

At the time of my research, horses were found only in the chiefdoms (e.g. in the Sandemnaab compound), where they usually graze outside the compound during the day and are kept in their own stables at night. Chieftains’ families use them only as mounts and objects of prestige, and horses are often seen at the great Feok festival in Sandema. The sacrifice of horses and the consumption of horse meat are taboo, at least in the homes of horse owners.

There is no horse breeding among the Bulsa. Young animals are bought from the Mossi in Burkina Faso. The breeding of mules is also completely unknown. When I enquired about this at the Sandemnab compound, I was met with great laughter.

Horse owners sometimes bury their horses in the cattle yard of their compound, and as referred to above, some have said that funerals will sometimes be held for horses.

8. Pigs (sing. duok, pl. die or dia)

Danlardy’s pigs

Before I completed my field research, the Agric Stations had tried to introduce pig breeding among the Bulsa. My assistant at the time, Danlardy Leander, was one of the first pig farmers in Wiaga to be quite successful. Because pigs were satisfied with waste or plants and fruit collected from fallow land or the bush, he saw the fact that there was no need to buy expensive feed as an advantage. The sale of pork might cause some difficulties, however, as Muslims and even some Christian refuse to eat it for religious reasons.

According to my informant Yaw (August 2024), pig breeding has increased in recent years and the sale of pork as a delicacy in the bigger Bulsa towns has become a common sight.

9. Chickens (sing. kpiak, pl. kpesa)

Chickens and guinea fowl probably play the largest role in enriching daily meals. In addition to being the most common sacrificial animals, depending on the wealth of the family, they may also be slaughtered for use as an ingredient in soups that go with millet and maize dishes. In such cases, they are cooked in the sauce just as vegetables and spices are; they are never roasted over an open fire as is sometimes done with a sacrificial fowl.

Chicken breeding

Chickens roam freely around the compound and its surroundings, and they must be caught for slaughter. Although the procurement, care and preparation of food are primarily in the hands of women, it is or was not permissible for women to kill chickens themselves and eat their meat and eggs.

At night, chickens sleep in a chicken coop (bukuri) made of earth, which is often integrated into the perimeter wall of an inner courtyard. This is also where the Bulsa prefer that the animals lay their eggs. However, chickens can often lay them in another woman’s courtyard, which may cause conflicts.

Eggs can be an ingredient in a sauce. Women can also sell them at the market or give them to a guest as a gift; they may also place eggs under the hens for incubation.

As noted above, chickens may serve as sacrificial animals at all shrines. They must be intact (e.g. they must not have any injuries or bald patches). Newly introduced chicken breeds, such as kpa-gbinggbing (with short downy feathers) and kpa-nanggbang (‘pigeon chicken’ with short legs), are taboo (kisuk) for sacrifices. According to tradition, a diviner (baano) determines the colour of the chicken before the sacrifice. The size of the chicken is arbitrary, although the diviner can specify a castrated or uncastrated cock.

After the sacrificial cut, the chicken serves as an oracle. Its dying position on the back or belly indicates whether or not the recipient has accepted the sacrifice.

10. Guinea fowl (sing. kpong, pl. kpiina)

Compared with other chickens, guinea fowl (Numida sp.) are considered quite ‘wild’ (i.e. less domesticated). At night, they often sleep in high trees near the compound, or more rarely in the bukuri; sometimes they have to be brought down from the tree by shooting with a rubber catapult.

In contrast to bush guinea fowls, the domestic ones are bigger and have a crest on their heads.

Although the secular use of guinea fowl in the household is similar to that of other chickens, there are some differences in the sacred sphere, where they are more strongly associated with women or the female sex. Guinea fowl are considered a favoured offering of women, and according to a diviner’s instruction, female recipients (e.g. ancestresses) are often offered guinea fowls, even if the donor of the sacrifice is a man.

Guinea fowl are never used for chicken oracles after their necks are cut.

11. Ducks (sing. kuribazuri, pl. kuribazue)

Europeans probably introduced the first ducks, and even today they remain rare among the Bulsa. They can be kept if there is a small pond near the compound where the ducks usually spend their time. Neither hunted wild ducks (goai-kuribazue) nor domestic ducks are permitted for use as sacrificial animals.

12. Turkeys (sing. tolotolo, pl. tolotolota)

Like ducks, turkeys were introduced by Europeans and are still very rare among the Bulsa today. Their use as sacrificial animals is also not permitted.

WILD ANIMALS (goai dungsa)

Waaung

A killed buffalo

The traditional hunting of wild animals, carried out by non-professional hunters with bow and arrow (and possibly with a muzzle loader), may also contribute protein to the meals of Bulsa families. All mammals (antelopes, gazelles, bush cows, wild boar, porcupines, monkeys, hares, etc.) are hunted, provided they are not totem animals and thus subject to a hunter’s killing taboo. Monkeys that are similar to guenons, known as ‘red monkeys’ (sing. waaung pl. wiiga) in Bulsa English, which are considered to be totem animals of the large group of Atuga-bisa, require particular mention here. Large reptiles, for example the monitor lizard (wuri, Varanus exanthematicus and yuk, Varanus niloticus) and snakes, are also classified as animals that adults hunt.

The author sitting on a crocodile from the Paga pond

Crocodiles (ngabta, sing. ngauk) populate some ponds and smaller pools to such an extent that it would be easy to kill some of them. However, there seems to be a kind of non-aggression pact here, as the crocodiles do not attack humans and vice versa. For example, I have observed weavers soak their rods in a shallow pond while surrounded by a number of crocodiles. When a crocodile was observed in a small pond in which pupils from Sandema Boarding School bathed on hot days, it did not prevent them from bathing.

Cage made by a small boy

Snakes (wiiga, sing. waab) sometimes also lose their fear of and aggression towards humans and enter compounds. They are usually regarded as sacred animals or even ancestral entities. In Sandema Kalijiisa, an old man gave shelter to a small snake in a clay pot in front of his compound, but the snake sought its own food nearby.

and enter compounds. They are usually regarded as sacred animals or even ancestral entities. In Sandema Kalijiisa, an old man gave shelter to a small snake in a clay pot in front of his compound, but the snake sought its own food nearby.

Boys of herding age also like to go hunting. They kill their prey without bows and arrows, using only their shepherd’s clubs. They usually pursue smaller game (e.g. mice, rats, lizards, small snakes, hedgehogs, etc.) than do adult hunters, and they typically roast them immediately over an open fire and distribute their meat among the shepherds according to set rules.

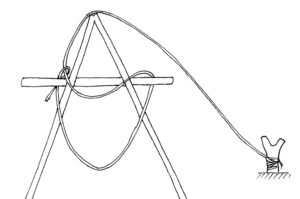

Trap for ground-nesting birds

Many children and young people will always carry a rubber catapult with them so that they can take shots at passing birds. If they find a fresh bird’s nest, they set a trap comprising a cylindrical mesh for smaller birds and a snare for larger ground-nesting birds (see Kröger 2001: 658–660). They also remove young birds from their nests and raise them in a self-made cage (nuinsa yikoari) until the birds are big enough to be eaten.

Skinned toads

Frogs, especially the large sari frogs, are sometimes used as ingredients in the sauce for a hot lunch or dinner. Bulsa generally abhor the consumption of toads, which are considered poisonous. However, in my two residential sections, Sandema-Kalijiisa-Yongsa and Wiaga-Badomsa, they are eaten after the poisonous skin has been removed.

Children and adults also likely eat a wide variety of insects in prepared or unprepared form. However, I am only aware of two particular species: termites and grasshoppers.

When the new, winged termite queens (sing. yuri or wuri, pl. yue or wie) leave their hive in their thousands and fly towards a light (e.g. a lantern), it is easy for people to catch them in a container of water, where they also lose their wings. After roasting them over an open fire they are eaten as a snack between meals.

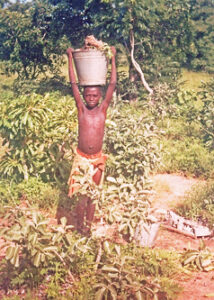

Collecting termite clay in the bush

Certain types of termites also play a major role as chicken feed. The chicken owner can knock pieces that contain insects out of a termite mound, or in the dry season, go into the bush every morning with a cheng pot filled with fertiliser, place it next to a termite hive and collect the pot the next day. Supposedly, the chickens eat only the larger female termites, whereas they either spurn the biting males entirely or only eat them after they have killed them. The collected termites (sing. mieri, pl. mie) are probably related to the very harmful togi termites, which also invade houses and cause considerable damage by destroying the wooden beams and perforating mud walls.

Among the many different species of locusts, some the bigger ones (e.g. nanchong) are sometimes eaten after roasting them. When large swarms of locusts raid the Bulsa farmers’ millet fields and almost completely consume the crops, it is easy to catch large quantities of the insects and eat them after roasting. One Bulsa explained to me that this is a very small compensation for the loss of the millet harvest.

A ceramic bee-hive in a tree

Even if they have to put up with numerous bee stings, younger boys, in particular, capture the coveted honey from hives built high up in the trees. Swarms of bees are also invited to settle in clay pots (e.g. samoansa) or large calabash containers suspended in the trees. Before the easy availability of granulated sugar, honey was probably more important for sweetening food.

Fish ingredients are part of almost every meal, but usually only in the form of small, dried saltwater fish (biila), which are sold in the markets. The cook will usually buy larger freshwater fish (sing. jum, pl. juma) – for example tilapia (paaring), mudfish (jum-goalik, Clarias sp.), sinsali (Alestes sp.), kungkook (Auchenoglanis occidentalis) or yibili/yibelik (Gnathonemus senegalensis or Petroclephalus?) – at the market if there are no specialised adult fishermen in the compounds who practice their trade all year round. The cook then roasts the fish on an iron grill, which she places over the mobile cooker (coalpot).

Fish grilled on a coalpot

Hand fishing, often in connection with driving the fish to a shallow bank, still occurs occasionally today, especially among shepherd boys; in contrast, fishing with the help of a poison extracted from the bark and leaves of the kan-gbegi tree (Balanites aegyptiaca), which was used more frequently in the past, has largely died out (Kröger 2001: 661–662). Poison fishing with modern chemicals poses a greater risk to the consumer. For example, the stomach of the fish must be completely emptied before consumption. Fish traps made from grasses or rods can be set out all year round.

Tilapia

Bulsa, who are full-time farmers but have some knowledge of fishing, usually fish at the end of the dry season, when rivers, lakes and ponds have very low water levels. (Kröger 2001: 660-670). They use a variety of fishing gear for this purpose:

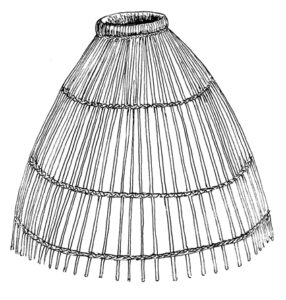

In shallow water, the fisherman puts a plunge basket (sing. sogi, pl. soga, see illustration) over a visible fish, then removes it by hand through the upper hole. In murky water, he employs this technique more quickly if he suspects fish are nearby.

Using the plunge basket (sogi) and fish traps (ngabisa, sing. ngabik) seems to be an older technique in Buluk, compared with nets. The large drag net (sing. neeb, pl. neesa or neeta), which is pulled by 3–4 men, and the small scoop net (sing. nisa-ngmiak, pl. nisa-ngmaasa), which is operated by one person, are pulled by the fishermen along the bottom of a shallow body of water. After a single pass, they collect the fish caught in the net’s mesh.

Fish trap (ngabik)

Sogi, plunge basket

The cross-net or gil-net (Buli: awuli), which consists of a long rectangle, was probably introduced from southern Ghana. Floats on the upper edge and lead weights on the lower edge ensure a vertical position in the water, and the gills of swimming fish are thus caught in the net. Similarly, the cast net (ngma-yugum) was also likely introduced from southern Ghana in more recent times.

Only children and young people fish with self-made fishing rods; for these, they buy only the iron hook (goatik pein) at the market. They fish in small or large rivers, or at one of the many reservoirs, and roast the fish immediately after catching them.

In the late 1980s, state-sponsored fishing projects were introduced in the area. For example, in 1988, I contacted the Fishery Training Centre at the Guuta Dam in Wiaga, which was run by a man from Lawra and funded by the Ministry of Agriculture in Accra. The project aimed to teach the Bulsa how to use modern fishing gear and improve techniques for catching, preparing, and preserving fish. Although the centre has since been abandoned, it remains a notable attempt to modernise local fishing practices during that period.

.

Cast net, ngma-yugum

Although wild animals increase the amount of protein in the food supply, compared with domestic animals, they do not play a major role.

References

Aduedem, Joseph

2020 The Art of Shepherding. The Origins of Conflict with Farmers in the Cultural Context of the Bulsa. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and History. No. 13: 49-53.

Kröger, Franz

1992: Buli-English Dictionary. With an Introduction into Buli Grammar and an Index English-Buli. Lit Verlag Münster und Hamburg

—, 2001: Materielle Kultur und traditionelles Handwerk bei den Bulsa (Nordghana). Forschungen zu Sprachen und Kulturen Afrikas (Hg. R. Schott), 2 Bände, Lit-Verlag, Münster und Hamburg

—, 2011: Mit Nahrung spielt man nicht! Kinder und Tiere in Nordghana. In: B. Huse, I. Hellmann de Manrique, U.Bertels (Ed.): Menschen und Tiere weltweit. Einblicke in besondere Beziehungen. Münster, New York, München, Berlin: Waxmann, p. 127-135.

—, 2010b Ziegen lieben PVC. Recycling und Müllprobleme in Nordghana. In: Ethnologik 2010, 1, pp. 37-39.

—, 2017: The Earth Cult of the Bulsa (Northern Ghana). Special Issue of BULUK.

Kröger, Franz et al.

2020 Buli Language Guide. Lippstadt

Schott, Rüdiger

1973 Kisuk-Tiere der Bulsa. Zur Frage des “Totemismus” in Nord-Ghana. Festschrift zum 65. Geburtstag von H. Petri, ed. K. Tauchmann, Köln and Wien, pp. 439-459.

— 1973/74 Haus und Wildtiere in der Religion der Bulsa (Nord-Ghana). Paideuma 19/20, pp. 280-306.

- Editors and Copyrights

- Two Sons of Buluk ordained in Wiaga to the Catholic Priesthood

- Bulsa schoolgirls sew sanitary pads

- Margaret Akanbang – The Mother of Doctors

- Animals, a Benefit for the Bulsa

- Events

- Elections 2024

- Joseph Aduedem: Gbanta Bogka – A Journey into Bulsa Divination Practices

- Obituaries

- Darius Adjong’s PhD thesis

- A German Anthropologist among the Bulsa: A Biographical Conversation

- POEMS

- MAIN FEATURE: BULUK OVER THE LAST HUNDRED YEARS