4. THE KUMSA FUNERAL CELEBRATION

Descriptions, fieldnotes and quotes from written sources

4.1 Preliminary remarks on the funeral celebrations

4.1.1 Terminological and methodological considerations

The first part of this study generally incorporated quotations from my field notes into a textual presentation or added to the final part of a chapter (‘Further information’); by contrast, in this section, the information about two major Bulsa funerary celebrations (Kumsa and Juka) had to be presented in a slightly different manner. Here, the field notes constitute the actual chronological framework for the funerary celebrations. Analyses and summaries are then provided as individual essays in the Appendix. Nevertheless, an attempt to organise the rites of the Bulsa funerary celebrations of various villages in chronological order is inevitably fraught with great difficulties, including:

1. Many rites (e.g. imitation, rattling at the mat, processions around the compound) accompany almost the entire funeral celebration or at least extend over several days.

2. Many rites take place almost independently of each other or in parallel.

3. There are differences in how individual villages and sections perform rites; some rites only occur in certain clan sections.

4. The chronological sequence of the rites is not wholly fixed but is discussed and determined by the old men in the kusung dok before the celebration begins. They also decide whether, for example, a day of rest will be included and whether some rites will be omitted or performed in another context of the ritual structure.

Considering these confounding factors, the list of notes presented in this section can only sketch a rough indication of what rites and other activities can be expected on a particular day and at a particular time. Their numbering has been added primarily for ease of reference.

Names: In this work, the first celebration of the dead is referred to as Kumsa (pl.), which accords with the common usage of many informants.

Azognab (2020) uses the Buli term kuub-kumsa. On this term, E. Atuick (2020: 37f.) writes: ‘…the kuub-kosik (the dry funeral) … involves the performance [Kumsa] of the funeral [kuub]… He calls the first funeral celebration “kuub-kumka.”’

In Ghana, the English term ‘dry funeral’ is used for a funeral celebration, in contrast to ‘fresh funeral’, which refers to the burial immediately after death. The word ‘funeral’ without an attribute usually only refers to the two funeral celebrations.

R. Asekabta (by letter): ‘I think kuub-kumka means the art of performing a funeral or how to perform a funeral and Kumsa is a short form of performing a funeral, for example ([as in] “kuumu kumsa ale chum”, [meaning] the performance of the funeral will be tomorrow)’.

F. Kröger, referring to the Buli-English Dictionary, offers the following definitions: Kumsa is a plural noun meaning (1) ‘mourning’, ‘weeping’, ‘crying’ or (2) ‘funeral’ or ‘the performance of a funeral’; kuub is a noun (plural: kumsa, kuuna) meaning ‘death case’ or ‘funeral celebration’.

Funerals attended by the author (and his assistants)

Kumsa funerals (or parts of them) were attended (unless otherwise noted) in the following compounds and time frames:

Atekoba Yeri, Sandema-Choabisa (fn 73,60–65) on 17–18 April 1973: the funeral celebration of a blacksmith who died at the advanced age of about 90 in March 1973 (he was said to have ‘still been fighting Babatu’). I only visited on the tika dai.

Asebkame Yeri, Wiaga-Chiok (fn 88,119a–121a) in December of 1988: held for a man, a married woman and two children. Only the gbanta dai was attended on 6 December 1988.

Wiaga-Sichaasa (fn 88,185) in 1989: the funeral of an old man and an old woman; a short visit was paid on 19 January 1989 (tika dai).

Akadem Yeri (fn 88,197+200a+b), Wiaga-Yisobsa in 1989: for almost a dozen men and women, visits on 28.January1989 (tika dai) and 31 January 1989 (gbanta dai).

Acha Yeri, Sandema-Chariba (fn 88,221b+222a) in 1989: Kumsa for a deceased married woman; a visit was paid on 5 March 1989 (gbanta).

Awuliimba Yeri, Sandema-Kalijiisa-Anuryeri (fn 88,223–226) in 1989: Awuliimba was the father of James Agalic, the assistant and informant of R. Schott and F. Kröger; visits were paid on all days (7–10 March 89)

Abanarimi Yeri, Wiaga-Chiok-Ayaribisa (fn 233a+b) in 1989: rituals for two married women (rites behind the compound), a returned daughter (in front of the compound) and a boy; visit paid on gbanta dai (16 March 1989)

Abapik Yeri, Wiaga-Badomsa (fn 88,305b) on 5 September 1990: Detailed information and photos were provided by Danlardy Leander.

Anyenangdu Yeri, Wiaga-Badomsa on 3–6 March 1991: the funeral celebration for Anyenangdu, the father of my main informant Anamogsi (photos and information were provided by my German friend and colleague, M. Striewisch as well as by Danlardy Leander). I also received detailed information and explanations from Anamogsi and other compound residents. Although I could not attend this funeral celebration in Anyenangdu Yeri, my residential compound, between 1978 and 2011, I received the most detailed material available for it among all funerals and could discuss all disputed questions until 2011.

Agbain Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa (fn 01,3a+b) in 2001: the visit – on the tika dai – occurred on 13 February 2001, and the gbanta dai took place over two days on 15 and 16 February 2001.

Atinang Yeri, Wiaga-Badomsa (fn 06, 6a+b; 10a, 27 January 2006): I could not attend the Kumsa in mid-March of 2005, but Anamogsi, Danlardy, and Yaw provided good information. It was held for deceased people from Atinang Yeri: Atinang, Angmarisi (Atinang’s younger brother), and Kweku (a young man). The following persons from Anyenangdu Yeri were included: Awenbiisi (Anamogsi’s son), Akansang (Asuebisa’s son), Agoalie (Anamogsi’s wife), and Adiki (Azuma’s young daughter). The imitator of Atinang was Atakabalie (Anyik’s wife); the name of Angmarisi’s imitator was forgotten by my informants. Ajadoklie imitated Agoalie. Per information provided in a supplementary letter from Danlardy (May 2004), when Agoalie died in her parents’ house, she was buried there, and a funeral celebration was held. Later, a second funeral was held in Anyenangdu Yeri.

Danlardy, in a letter dated 7 May 2004 (fn 2002,3,55a*), wrote that women’s funerals could be held twice.

Agaab Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa-Chantiinsa (fn 08,15) for two male and five female deceased people; visitation occurred on 17 February 2008 (kalika); 21 February 2008 was the gbanta dai.

Adiita Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa-Guuta in February 2008: The kalika took place on 22 February and the gbanta occurred on 24 February 2008 (the tika dai was cancelled). I (F.K.] could document only one late phase of the gbanta myself.

Ataamkali Yeri, Wiaga-Longsa on 25–29 January 2011: compound of the kambonnaab and earth-priest Afelik (the tika dai, kpaata dai, and gbanta dai were observed).

4.1.2 The soul (chiik) of the dead

The following text was adopted in an abridged form from F. Kröger’s ‘Religious and rebellious elements in Bulsa funeral rituals’, an article published in BULUK’s 10th volume (2017), pp. 97–99.

Although the Bulsa are often regarded as one of the best-studied ethnic groups in Northern Ghana, their funeral rituals – with their unique interweaving of countless religious rites and various secular acts – have never been the subject of a general monographic publication.

The basic religious idea of funeral celebrations may lie in preparing the transition of the deceased from the land of the living to that of the dead. In better understanding this process, it is necessary to clarify which parts of the human personality are affected by certain rites concerning the deceased. The Bulsa attribute multiple personality components to each person.

One of them is nyuvuri (cf. nyueri, ‘nose’, and ‘vuum’ life) or the ‘pulsating life’, which is mainly revealed in the respiratory movements. Another component is the ‘life force’ or pagrim, which is demonstrated in physical strength and immunity from and resistance against harmful spiritual influences, including ghosts, witches, and bush spirits (cf. Kröger 1978: 143–145). The personality components mentioned so far play a subordinate role in burial and funeral rituals. More important are the functions and activities of the following three components (ibid. 140–143):

(1) the body (nying, pl. nyingsa)

(2) the wen, a divine power associated with an individual, but worshipped by sacrifices to a shrine outside the body (Kröger 1982: 6ff, 2003: 254ff)

(3) the soul (chiik, pl. chiisa)

The dead body and its odour (piisim) may be a great danger to the living – only the initiated gravediggers know the correct way to deal with them. The corpse of a deceased person is usually buried on the day of death. This activity occurs within the narrow circle of one’s family (cf. 3.4 and 3.5).

The veneration of a deceased person’s wen often intensifies only years after the burial. Although the wen-shrines of the deceased exist in the compound during the funeral celebration, sacrifices to these or any other rituals concerning them are not a part of the celebration.

Among the religious events of the first funeral celebration, the rituals concerning the soul (chiik) of the dead are paramount, as explained below. After the burial, the soul of a dead man is represented less by the grave than by the sleeping mat (called tiak; rolled, it is called ta-pili) on which the dead man died – it is regarded as the abode of his soul. In the past and even in some present compounds, this representation of the dead in the ta-pili entailed leaving a small dish of food in the ancestral room every evening and removing the untouched food the next morning. The food is left behind because the dead man did not consume it in a material sense, only taking its power or substance as nourishment. Afterwards, this food can be consumed by humans or fed to animals. In addition, known preferences of the deceased, such as his enjoyment of beer, kola nuts, or tobacco, are respected by placing these luxuries in the ancestral room for some time.

The soul of the dead is not always enclosed in the mat or hovering around it. It can, for example, visit the deceased’s body in the grave (boosuk). A small hole is left in the ceramic cover of the grave, so the soul can have free access until the end of the final funeral (Juka).

Information about the soul

According to information from Gbedema, some Bulsa (usually thoughtlessly) invite the ancestors or the dead to eat with them by uttering the following sentence before eating saying ‘Ni de abe ni ge te mu’ (‘You eat before you give me’). Moreover, a ceramic pot (liik) with drinking water – placed in one corner of each courtyard – should never be empty so that recently deceased persons and ancestors can serve themselves there.

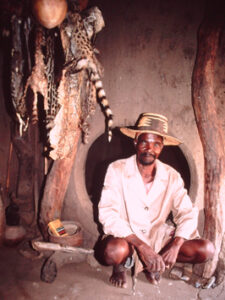

When the head of a compound (yeri-nyono) dies, either his eldest brother or his eldest son performs all important rituals and is responsible for the deceased’s soul. However, he must inform his predecessor about every important ritual in the compound by speaking to the deceased’s soul, which resides in the mat (see photos).

The acting head of the compound, Leander Amoak, informs his ancestor Abonwari about a ritual event.

Godfrey Achaw (fn 73,178): A soul can be strong (powerful) or weak. A person with a strong soul is difficult to kill or harm.

The soul can leave the body at night and revisit all the places it has visited during the day (and others). If a ghost haunts the soul at night, the sleeping person will dream about it. After death, the soul of a witch becomes a ghost (kok). Other people’s souls go to Naawen (God) after death or, as others say, to Ajiroa, the realm of the dead. When I [Godfrey] die, I [will be] reborn with my body in Ajiroa, but strangers [will not be able to] see me. At the same time, my body remains present in the grave. The food that family members place in the room where the mat is located is intended for the chiik of the deceased. Anyone can eat the food later except for the spouses of the deceased.

Apusik (Sandema-Kobdem? fn 88,126b): The soul of the deceased moves to the realm of the dead, Ajiroa, after the Juka celebration. Others say that the soul continues to dwell in the bui (granary) of the deceased person. When the soul visits its old compound from Ajiroa, it will live in the bui. The [round] stone (tintankori) on the [bui’s] floor also symbolises the soul.

Danlardy says in his examination paper (fn 86,12a): Every person (nurbiik) has three souls (chiisa): (1) one goes to God after death; (2) one lives on in the dead body; (3) the sitana soul is annihilated at death, i.e., it dies with the soul. The third soul tempts the living person to do evil.

Margaret Arnheim (fn M79,8b): She herself was afraid of cows. She had a dream that she was being chased by cows. The neighbours told her that witches were haunting her soul.

Azognab 2020: 56: The fourth interview question to the [15] respondents was, ‘What happens to the human person after death?’ All the respondents answered that the chiik (soul) of the person hovers around the ta-pili (death mat), the boosuk (grave), and the dalong or kpilima dok… until the death and funeral rites and rituals are properly completed.

4.1.3 General information on the funeral celebrations

(See also 7.1.–7.5 and F. Kröger 2017: 97–113: Religious and rebellious elements in Bulsa funeral rituals)

4.1.3.1 Abolition of taboos (kisita, sing. kisuk) of everyday life

Godfrey Achaw (fn 73,32): If adultery occurs during a festival, it is not considered adultery, and a wife need not inform her husband. Another cancelled taboo during major festivals is that a Kalijiisa man can marry a Kobdem woman (however, marriage within a section is not allowed). This lifting of taboos is limited to (1) the funeral of a great old man, (2) the Fiok harvest festival (November–December), and (3), in some instances, sacrifices to the land.

Apusik, Sandema (fn 88,226b): At a funeral, the following taboos are lifted:

1. Suma (round beans) and tue (small beans) are cooked together in one pot

2. Cloth or clothing may be placed on the roof of the kusung or kusung dok (otherwise, this placement is forbidden)

3. Certain songs may only be sung at funeral celebrations

4. One may stop at the main entrance for a while (nansiung)

5. Otherwise, you are not allowed to mourn inside or outside the cattle yard (?)

6. Sexual permissiveness exists only on the kpaata dai

Yaw (fn 06,34b): At funerals, the following taboos are abolished: (1) one may sing funeral songs; (2) rolled-up mats are placed with their tops to the ground; (3) usually, one may not walk over lying mats – if this happens, you must jump back and walk around the mat; if an animal steps over the mat, it is killed immediately – but they can be walked over during funerals; (4) sex outside the compound is permitted but is otherwise strictly taboo; (5) cooking suma and tue beans in one pot is permitted but is otherwise taboo.

Yaw has never heard of a cancellation of the exogamy or incest commandment. Standing at the entrance is also forbidden at funerals, according to him, but according to other information, it is permitted.

(Yaw, fn 01,2b): Imitation at a worldly festival (tigi) is taboo (kisuk).

Yaw: Blowing the kantain horn trumpets is only permitted during funerals.

Danlardy, Yaw, et al. (fn 94,22a): The eldest son of a deceased person may not wear that person’s clothing during his lifetime. At the Kumsa, he dresses in these clothes before the impersonator puts them on.

U. Blanc (2000: 55, 136f and 145): The intonation of the rhythms during zong zuk cheka (playing music on the flat roof) is taboo outside the funeral celebration (kisuk).

4.1.3.2 Further general brief information on the Kumsa funeral celebration

Funerals for women

F.K.: Funerals for married women are typically held in their husband’s compound together with those for deceased men.

If a funeral celebration is held for women only, some acts, such as the war dances, are omitted altogether. Furthermore, if the burning of the mats is postponed to the first day, the entire second day is cancelled (this is also confirmed by Aduedem).

Timing of the celebrations

Godfrey Achaw (fn 73,47): The first funeral celebration occurs in the next dry season or years later.

(fn 73,54b): The timing of funerals among the ko-bisa in Sandema-Yongsa must be precisely coordinated. If one compound is ready to perform a funeral, it must wait for its turn. However, after 20–30 years, the four houses of the ko-bisa of Achaw Yeri will probably become completely independent (without any obligation to wait).

Yaw (fn 01,2b): Unlike in Sandema, funerals in Wiaga are not allowed to start on a market day. In Sandema, many individual rites or other acts are omitted on market days.

Aduedem 2019: 12f: On average, the [Kumsa] takes three or four days for the male or female [deceased people], respectively, or four or five days for an elderly man or woman of status, respectively. The timing of when final funeral rites of mixed sexes are celebrated together depends on the part of Buluk; in Chuchuliga and some other parts, male funerals take precedence, whereas, in Sandema and the southern part of Buluk, female funerals take precedence. Thus, the days [proceed] according to whose funeral takes precedence in cases of mixed celebrations.

Funerals that are mistakenly held for living persons

Akambonnaba, Cape Coast (fn 73,53a): If someone’s funeral was held, he is presumed dead. Akambonnaba’s father had to drive an ambulance during the war. When his home compound in Siniensi received the news that their father had died in the war, a funeral was held for him. Although this father reappeared, he was presumed dead and was never allowed to reappear in Siniensi (though his children were).

Godfrey Achaw (fn 73,53a): Godfrey also knows of a case where a funeral celebration was held for a man from Sandema who had gone missing and was supposed to be dead. After his return to the Bulsa area, he was no longer allowed to go to Sandema. When he passed there in a car, he pulled a scarf over his head. He was neither allowed to accept gifts from Sandema or give gifts there. People from Sandema were allowed to visit him outside Sandema.

Margaret Arnheim, Gbedema (fn M20b): During the war, funerals of living people were held by mistake. When they returned, they were accepted back into the community. It is said that they will have a very long life.

Miiga funerals

Ritual miiga from Wiaga-Chiok

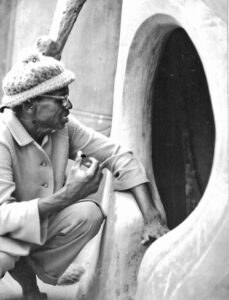

Leander Amoak and a blacksmith (Ako?) from Wiaga-Chiok (fn 73,151):

For very important men of the blacksmith section, part of their funeral celebration is held while they are still alive. A pair of blacksmith’s tongs (miiga) that are transformed into a fly whisk with leather fringes plays an essential role in this. The whisk is used to drive away evil spirits. Several cows are sacrificed at a miiga funeral but not, as elsewhere, on the ash heap (tampoi). If the person later dies, no further animals are sacrificed. A few weeks ago, a very sick man was honoured with such a miiga funeral but died shortly afterwards. Leander had never heard of a miiga funeral. A miiga was made for me (F.K., see photo), which is now in the Völkerkundemuseum Werl.

Thomas Achaab from Sandema-Choabisa (fn 73,151b): The miiga also plays a major role in Sandema-Choabisa when a great old man dies. On the day of death, the miiga is decorated with leather strips, and an iron rod is carried around the house.

The deceased person and his funeral celebration

Godfrey Achaw (fn 73,55a): If a man dies very suddenly (e.g., through a tanggbain), he does not receive a funeral celebration. His death mat is burnt on the day of his death, and rarely, he is also buried as an adult man outside the compound. Women who die in childbed are usually given a funeral celebration. Deceased infants up to about three years of age and with no younger siblings do not receive a funeral celebration.

Yaw (fn 97,39b) The funeral celebrations of earth priests and smiths are completely similar to those of other persons.

Yaw (fn 23b): Women who have never had children (a daughter by another man would here count as a child) receive the funeral celebration of a man.

Further prescriptions and prohibitions

(See also 4.1.3.1: Lifting of taboos of everyday life at death celebrations)

Godfrey Achaw Kalijiisa-Yongsa (fn 73,48a): During the three (for male dead) or four days (for females) of a funeral, all women sleep in the compound, and all the men sleep outside.

(fn 73,69): Godfrey and his friend, John, who is from the neighbouring compound and belongs to Kalijiisa Chariba, were born on the same day. If there is a funeral celebration at John’s house, John must sleep and eat at Godfrey’s compound (Achaw Yeri) until the celebration ends, even if Godfrey is not present. John can attend all the events of the celebration from there.

F.K. observation (fn 94,11a): When I visited Rita Atuick to observe her making soap, her brother – the new chief of Wiaga – was lying in the kusung of her house. He was not allowed to enter the chief’s compound during the four days of his predecessor Asiuk’s funeral celebration.

Conflicts and harms

Danlardy Leander (fn 88.1): After Leander’s and before Adiak’s death, there was much quarrelling between Leander’s children and Adiak. Adiak urged Danlardy to hold the funeral celebration of Abonwari (who died probably in the nineteenth century), as this would have made him the kpagi of the Ayarik-bisa. When Adiak’s wife died, Danlardy wanted to combine her funeral with that of Abonwari, Atiim, and Leander. However, Adiak held his wife’s funeral without the others.

Ayarik Kisito (fn 73,319b): A harmful charm (jugi, pl. juga) is only used at funeral celebrations. This jugi is a black powder of crushed medical charcoal that is sprinkled on the ground. Anyone who steps on the charm catches elephantiasis.

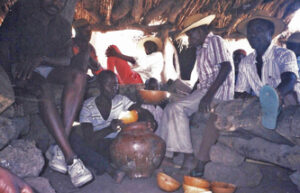

Musical instruments

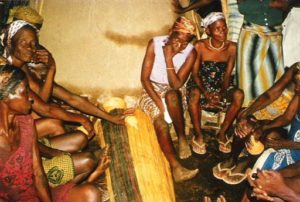

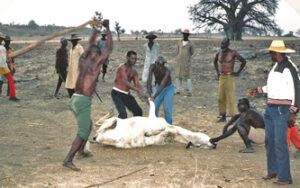

Music group at Anyenangdu’s Kumsa celebration

Leander Amoak (fn 81,30): The following instruments are played at funeral celebrations: [F.K. at processions around the house?]: six flutes (wiisa), two cylindrical drums (ginggana), two calabash drums (goa), one hourglass drum (gunggong), and one pair of sinyaara rattles.

For war dances, musicians play one dunduning drum, one double bell (sinleng), and one kantain horn trumpet (similar to the namuning horn trumpet).

For fun and dancing, one calabash drum (gori) and one pair of sinyaara (wickerwork rattles or round calabash rattles) are played.

Further information

Godfrey Achaw (fn 73,60a): The funeral celebration of Atekoba (Choabisa) on 17 April 1973 was organised by the head [kpagi] of Choabisa, whose eldest son had to pay for the costs. Atekoba was buried in a residential courtyard [F.K.: ma-dok?] of his compound. At 11 p.m. before the first day, it started to rain (which was a good sign). It was believed that Atekoba had caused the rain. Men climbed onto flat roofs and performed war dances without helmets and with an axe. Such dances are also performed when rain starts after a long time of dryness.

Margaret Arnheim (fn M52b): Margaret went to the funeral celebration in a completely different section in Siniensi (with Mary Assibi, who was distantly related to the concerned compound) because there was a large ‘packed funeral’ there – the funeral celebrations of many people were combined into one. The phrase used was ‘Ba tigsi kunanga ngomsi’ (‘They “pack”/“collect” funerals’).

(fn M,61a): If only the Kumsa celebration but not the Ngomsika (Juka) celebration is performed, one says ‘nye kuub zaani’ (‘to perform half of a celebration’).

4.1.4 Preparations and planning for the first funeral celebration

Before the funeral celebration, the costs for animal sacrifices and other expenditures are calculated, and planned invitations are discussed thoroughly.

4.1.4.1 Planned invitations and cost breakdowns for Asik Yeri, Badomsa (see genealogy in Appendix 2)

New plans for timing and cost continue to be made for the outstanding funeral celebrations for the dead (including Abonwari, who died in the nineteenth century). To my knowledge (F.K.), they have not yet been realised to date (2023).

Danlardy Leander (fn 86,7a): The pending funeral celebrations in Asik Yeri will probably be held in two sections: first, the older generation (Abonwari) and then the younger generation (Atiim and Leander). Adiak urged Danlardy to perform the funeral celebrations and insulted him. Based on this, I (F.K.) should not visit him again from now on.

Danlardy Leander (fn 2002/3,55a*): Regarding plans for Leander’s funeral, Asik Yeri will be renovated beforehand, and official invitations will be sent to the families of Ayarik-bisa, Adum Yeri, and Aluechari. The funeral will be combined with those of Abonwari, Akanzaaleba, Atiim Maami, Atoalinpok and Aparing. It will be organised by Michael Atiim (a nurse), Danlardy, and the younger siblings. They also provide money for the nang-foba animals, cheri sacrifices, and millet porridge (saab), as well as rice to feed the guests and malt (kpaam) for millet beer.

Invitations and costs for the planned funeral celebrations in Asik Yeri

Danlardy Leander, (fn 06,5a) 24.1.2006: A preparatory meeting was held in Asik Yeri on 7 January 2006. The following ‘uncles’ and ‘aunts’ (i.e., matrilineal relatives), or representatives of their lineages were to be invited to the planned funeral celebrations (of Leander et al.) (see genealogy in Appendix 2):

1. Wabilinsa: Awon Yeri

2. Dokbilinsa: Achambe (Achagbe?) Amoak

3. The Gbedema chief’s house: Akan-nyemi

4. Bilinsa: Akpadiak

5. Longsa: Ajaana

6. Chiok: Assibi

7. Kadema (Atongka’s relatives)

8. Abavare (Atongka’s relatives in Chiok)

The following funerals were obligatory to be attended beforehand (including those of matrilineal uncles and aunts):

1. Abonwari’s wife’s funeral in Gbedema was to be attended by 2–3 people from Asik Yeri; gifts of kola nuts and two gallons of alcohol were planned.

2. The whole of Badomsa was invited to attend Akan-nyemi’s funeral at the Gbedema chief’s compound.

3. For Ayarik, Apaarichang’s son, drinks, kola nuts, and gunpowder would be provided.

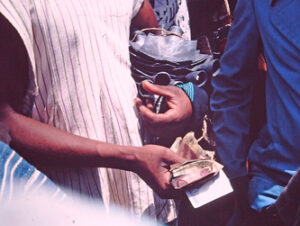

All the planned funeral visits would need to be provided with the following:

One gallon of akpeteshi for the ‘welcome’, one gallon for ‘intention’, two gallons for the Badomsa people who go along, and one gallon for the ‘dispatch’ (?).

The total costs paid by Asik Yeri for funeral visits and the planned celebration in Asik Yeri would be as follows:

Together, seven gallons of alcohol 385,000 cedis (7 x 55,000 cedis) [2006: 35.8 €]

Three bottles of gunpowder 105,000 cedis (3×35,000 cedis) [2006: €9.77]

One calabash of kola nuts 50,000 cedis [2006: € 4.65]

One goat for 100,000 cedis [2006: € 9.31]

Five bowls of sprouted millet for 50,000 cedis [2006: € 4.65]

Four bowls of rice 68,000 cedis [2006: € 6.33]

Soup ingredients (e.g. vegetables and spices) 142,000 cedis [2006: € 13.22]

Total 900,000 cedis [2006: €83.71]

The 900,000 cedis would have to be raised by the family members who earned money: Danlardy, as the headmaster of the Arabic School; Anangkpienlie, a trader; Michael Abaala, a nurse; etc.

Each would need to pay 150,000 cedis [2006: €13.96]. Michael’s wife, Atta, would collect the money.

The ‘greeting’ was planned for February 2006, and the funeral for March or April 2006.

The sacrificial animals needed for the funeral at Asik Yeri were as follows:

(1) Nang-foba animals (at the tampoi) for deceased males and females of their lineage:

(a) For Abonwari, Atiim, Leander (†1985) and all deceased daughters: a sheep and chickens.

(b) For married women: one sheep and one chicken.

(c) The following women received the requisite sacrificial animals:

Atoalinpok (Danlardy’s stepmother, †1994), Maami Atigsidum (Danlardy’s stepmother, †1995), Achimpoore (Atiim’s wife, Danlardy’s FBW), and Abonwari’s wife, who was abducted by slave hunters in the nineteenth century (funeral held in Gbedema?)

(2) Cheri sacrificial animals included four goats for the married women and one sheep for all the men.

Other expenses for the kpaam tue included sprouted millet for millet beer, some of which is offered to relatives before the celebration begins, shea nuts, small beans, and round beans.

Danlardy Leander 1 June 2006 (fn 06,4b): In Asik Yeri, a three-day funeral celebration was planned for the following men and ‘daughters’: Abonwari, Leander Amoak (†1985), Atiim, Ajaring (Atongka’s father’s sister), Paulina Abaala (Michael’s wife, †2002), and Adaanlie (Danlardy’s sister). On the last day (the gbanta dai), the funeral celebration for the wives begins (without a day of rest in between): Abonwari’s wife, Atoalinpok (Leander’s wife, †1993), Achimpoore (Atiim’s wife). This celebration would last five days, with one day of rest included.

4.1.4.2 Planned invitations and dates: Apok Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa-Napulinsa

Yaw Akumasi (cf. genealogy in Appendix 3)

(fn 02,21): In Apok Yeri, there was a long discussion about which ‘uncles’ (matrilineal relatives) and ‘in-laws’ (wives’ families) should be invited to the upcoming funeral celebrations. Relatives of one’s section were not invited because they were the organisers. It had to be determined which funeral celebrations should be concluded beforehand, such as for Asuk, the deceased husband of Amelinyang(a) from Gbedema. The san-yigmoa, Kwame Atongdem (chief’s house), would be sent to Gbedema with a hoe blade, a bracelet, and tobacco. The three heads of Apok Yeri (Ayuekanbe), Ayienyam Yeri (Abasimi), and Akanguli Yeri (Asiidem) – but not elders from the distant Napulinsa (see Apok Yeri genealogy, Appendix 3) – would have a decisive say in the planning.

(fn 02,23b): Some decades ago, Amelinyanga brought Awenlemi, her doglie, to Apok Yeri. There, Amelinyanga gave birth to Akalabey and Francis. She then left Apok Yeri in Asuk’s lifetime, while Awenlemi remained. When Awabilie, Awenlemi’s daughter, died (before Asuk), her mother’s hair was not shaved. After Asuk’s death and though previously married elsewhere, Awenlemi returned to her parental home in Gbedema. Thus, Asuk’s funeral could not be held because one of his wives (Awenlemi) was absent. Apok Yeri had already greeted the Gbedema Compound (2002), and animals (sheep and goats) would be sent to Gbedema, as Apok Yeri did nothing when Amilenyanga died in Gbedema. This was a kind of restitution for the animals given to the vayaasa at the funeral. If a particular shrine in Gbedema still required an offering, they would also be obliged to pay for that. Bracelets and a nabiin-soruk necklace were also sent to Gbedema because Awenlemi’s daughter, Awablie, died. Awenlemi was to wear the necklace and bracelets when she came to Apok Yeri and during the funerals. She would be able to take them off later, but they would remain her property. Sending the animals and the jewellery was also indirectly a request for Awenlemi to return to her children in Apok Yeri. When she arrived, the hair on her head would be completely shorn. If the hair had grown back by the time of the funeral, it would be shorn again. At the funeral, she was the pokogi (widow) of Asuk. When Gbedema people came to Apok Yeri, they would bring a big busik basket full of za-monta and peanuts ‘for taking her daughter Amelinyanga back to her husband’s compound’ (‘Ti liewa a kuli wa chorowa yeni’). They would never mention that she has been dead for a long time. Shaving the hair of the head is called pukongta bobika (bobika = ‘binding’, meaning that she is bound to the inside of the dalong for a time).

(fn 06,35b): About four days before the funeral of Yaw’s father-in-law in Aluesa Yeri (Sichaasa), Asiidem, Yaw’s san-yigmoa – and whose mother came from Sichaasa – will come to Apok Yeri after a messenger from Aluesa Yeri has informed him (Asiidem).

Yaw, 19 December 2002 (?): Angmanweenboa from Apok Yeri married a Wabilinsa man. When her stepmother in Apok Yeri fell ill, she returned to her parental home with her young son Apung (Yaw’s father’s father). Apung stayed in Apok Yeri, and his Kumsa funeral was held there (Juka not yet). Wabilinsa should have requested the funerals of Angmanweenboa and Apung. Apung then married Angmanyieba from Sandema-Bilinsa in the south. Ayigmi, her full sister who lived with her uncle (in her mother’s house) in Azong Yeri in Kubelinsa (Goldem?), wanted to please her host house. She stole the death mat from her mother’s house in Bilinsa and brought it to Azong Yeri. Ayigmi married a brother of Akai (Badomsa) and is the only person living in his compound. Her daughter, Asagipok, now lives in Asisapo Yeri (Badomsa) after a divorce. Asajipok’s son, Mahmudu, lives in Bolgatanga.

In Apok Yeri, they try to find compromises. For example, they wanted to get the mat from Azong Yeri and then give it to Amoboari Yeri in Bilinsa. If the mat was there, Bilinsa people could attend Ayigmi’s funeral celebration in Badomsa (otherwise, they could not). When Angmanyieba died, Bilinsa people came to Apok Yeri to greet him but were not allowed to mourn (kisuk). Others – including people of Azong Yeri – who come to Apok Yeri are also forbidden (kisi) to mourn and can only greet the inhabitants. However, Yaw, who was now in charge of his father’s father’s (FF) affairs in Apok Yeri, was allowed to mourn Angmanyieba. But there was no official announcement (kuub darika) of the death. There were no real conflicts between the mentioned houses, only ritual prohibitions. Wabilinsa needed to come to Apok Yeri with a sheep to bring Apung’s funeral to Wabilinsa. Yaw could visit the Wabilinsa compound but not stay overnight; otherwise, his life would be in danger. Yaw and his father, Akumasi, are still believed to be relatives of Apok Yeri because Apung’s and Angmanyieba’s funerals were held there.

4.1.4.3 Planning funerals in Anyenangdu Yeri, Wiaga-Badomsa

Akanpaabadai, 30 January 1989 (fn 88,199b): In a few years, Anyenangdu’s funeral would be celebrated, but nothing had yet been finalised. In addition, the funeral celebrations of Atuiri, Angoong, Atuiri pooma (five!), Anyik pok, Afelibiik pooba baye, Amuning Ali (Atinang yoa), and Akanminiba (Akai’s father) would be held. Later, the planned celebration was held in 1991 without my (F.K.) presence.

Danlardy about Anyenangdu Yeri, 12 February 2007: Anamogsi performed the Kumsa funerals of Agbiera on 1 January 2006 and of Akanpaabadai and Akumlie in Anyenangdu Yeri on 28 December 2006. He performed the Juka funeral on 3 January 2007ff. Not many people were there due to a dispute with Akanjaglie after Anamogsi’s sons had torn down parts of her compound. The dispute was settled before the funerals, and Akanjaglie participated in the funeral celebrations as Akanpaabadai’s widow.

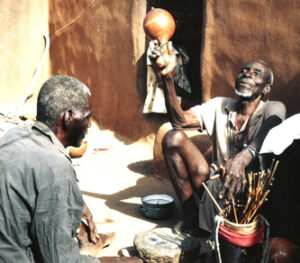

4.1.4.4 Divination visits and the leaders of funerals

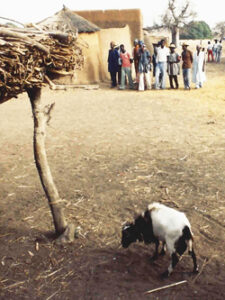

Divining session in Wiaga-Badomsa

Before a funeral celebration is held, the compound head always pays numerous visits to diviners. Immediately before the start of the Kumsa celebration, he asks the diviner about the organisation of the funeral and about its leaders (elders, kuub nyam), who will make all the important decisions. Some leaders always come from a different section, which is usually a neighbouring one. A funeral celebration in Wiaga-Sinyangsa-Badomsa is probably always conducted by elders from Sinyangsa-Kubelinsa; for Sandema-Kalijiisa, I know of two funerals in which elders from the neighbouring Bilinsa section took over the leadership.

Danlardy Leander (fn 94,86b): For the funeral celebrations of Abonwari, Atiim, Leander, Atoalinpok, and Maami, this neighbouring section [was] Kubelinsa, and the selected elders arrived at the funeral compound shortly before the Kumsa began. They took their seats in the kusung dok (meeting room with closed walls), discussed the feast, and then were served millet beer and millet water.

4.1.4.5 Preparatory meeting one or more days before the celebration

Serving millet beer in the kusung

Anyenangdu’s Kumsa was held on 28 February 1991: Three days before the start of the celebration of Anyenangdu’s Kumsa, the organisers and elders from Anyenangdu Yeri consulted with each other in the kusung. Anamogsi, Atinang, Ansoateng, Atupoak, Akayabisa, and Akabre conferred separately in the cattle yard (see photo). They sent some of their party to the elders in the kusung to inform them of their decision (e.g., a separate funeral for Aluechari’s sons should be held).

The heads of the ko-bisa have gathered for a separate meeting in the cattle yard.

The elders were sent a pot of pito and a bowl of millet water; Akperibasi (Abasitemi Yeri) distributed it (see photo). Then they were shown five bottles of gunpowder and the shotguns (da-guunta, ‘buried guns’) to prove that they are well prepared for the funerals; the gunpowder was tested by firing a shot.

Aduedem 2019: 13: …the sons or relatives call the yie-nyam (landlords) to the house and inform them that they should perform their funeral for them (ni kum ti kuumu te ti). When they [select] the day…another announcement [will be sent] to all that they will be removing Mr A’s mat the following day (as usual, young men are sent to the houses to inform them).

4.1.5 Going to the market

The procession to the market seems to be rarer and less official in Wiaga than in Sandema. In any case, the deceased person must have been old and respected. I only witnessed this procession once during the Juka celebration at the Wiaganaab’s compound, which is situated immediately next to the market.

Godfrey Achaw (fn 73,46, 49a): On the market day before the funeral celebration, all the musicians parade to the deceased’s house. They then go to the market with residents, neighbours, and relatives. The men of the section each wear animal skin (of cows, goats, or sheep) around their hips and an axe (liak) over their shoulders. They parade around the market and announce that a funeral celebration will be held the next day. There is much drinking, and the chief mourner must supply the musicians with millet beer. The music group consists of drums (especially ginggaung), flutes, and horns. In the evening, everyone moves to the house of mourning and stays there. The funeral celebration begins shortly after noon, as people want to go home in the morning to feed their cattle, etc.

4.2 Chronological listing of the events of the Kumsa celebration

The course of the first celebration for the dead extends over 3–4 days; if this includes a day of rest (vuusum dai), the celebration may last up to five days. The frequently expressed assertion that the celebration of a deceased woman lasts four days and that of a man lasts three days does not always seem to be in line with the practical application of funeral rites, especially as some (e.g., war dances) are omitted in a celebration for only one or more women (e.g., in Longsa 2011). The names for the individual days of funeral celebrations are manifold:

The first day can be called the kalika (sitting), kuub kpieng (great funeral celebration), or taasa yiika dai (removal of mats).

The second day is called the tika dai (assembly day) or leelik dai (war dance day). Azognab also calls it the kuub-guka dai (see below) and yiili siaka dai (day of dirge).

The third day is called the kpaata dai (shea butter day) or kpaam tue dai (shea butter and bean day).

The fourth day is called the gbanta dai (divination day).

A rest day (vuusum dai) can be inserted before the kpaata dai (see above).

This sequence of events has been confirmed many times by my visits to funeral celebrations in Wiaga and Sandema and by my informants.

E. Atuick (2020: 38f.): Where a deceased woman is among those for whom the funerals are performed, there is a mandatory rest day on the third day called vuusum [resting]. Where the funerals involve only deceased males, there is no vuusum during the funeral performance.

Azognab (Sandema-Abilyeri, information from Siniensi) describes the sequence and significance of the first two days differently from the above scheme:

The following information was gathered in an interview on the number of days taken for the dry funeral [endnote 70]. The period for each funeral ranges between three and four days, but that of chiefs and yeri-nyam or kpaga (elders who are family lineage heads) may be longer. The first day of the ‘dry funeral’ celebration is the kalika dai (literally, the ‘sitting day’). The kalika dai is applied to funeral celebrations of traditional leaders such as chiefs, teng-nyam, and yeri-nyam (family heads). The second day is the kuub-guka dai (literally ‘the day of burial’, when the death mat that represents the deceased person is disposed of). The ordinary funerals start on this day; in this case, the day is called the yiili siaka dai (literally, ‘the day of dirge’). This is followed by the kpaata dai (‘shea butter day’). However, if the deceased was a female, a chief, teng-nyono or a family head before his death, one day of rest, described as the vuusum dai, is observed before ‘the shea butter day’ [endnote 71]. The fourth day is the gbanta dai (day of divination) [endnote 72].

4.2.1 First day: Kalika or kuub kpieng dai or taasa yieka dai (removal of the mats)

4.2.1.1 Informing the ancestors through sacrifice (not observed)

4.2.1.2 Gathering of elders and neighbours

Awuliimba’s Kumsa, Sandema-Kalijiisa (fn 88,223a), 7 March 1989: At around 10 a.m. (or before?), the first consultations of Awuliimba’s sons and the co-organisers from the neighbouring Bilinsa section were held in the kusung dok. James Agalic explained to those present why some white people also wanted to participate in the rites.

Anyenangdu’s Kumsa, 3 March 1991: In the kusung, elders from various houses in Badomsa gathered: Angoong Yeri, Atinang Yeri, Atuiri Yeri, Akanming Yeri, Adaateng from Adaateng Yeri, Asante from Atengkadoa Yeri (= Asisapo Yeri), Akutinla (= Akutuila?) Yeri, Abui from Anue (= Aniok) Yeri, Akannyeba from Ayoaliyuema (= Ayualiyomo?) Yeri, and Amanchinaab from Amanchinaab Yeri. The following men were present from Kubelinsa: Akpiuk, Ayiruk, Adaanuruba, Aniyeng. In addition, the elder Ateng-yong from Akan-nyevari Yeri and Akayeng and Brunu from Akayeng-Yeri (all Sichaasa), were present. Kubelinsa led the discussions, but Badomsa men always joined in. After a consultation, the elders in the kusung reaffirmed the decision that it was right to bring forward the funeral of Anyenangdu (see 4.1.4.5); two younger men – Asante and Abui – went to Anamogsi to inform him of the elders’ agreement. After being served millet beer, they accepted the funeral.

Funeral at Atinang Yeri (fn 06,6a), data collected by Yaw: In mid-March of 2005 from 2.00–5.30 p.m., a meeting took place that was attended by the Badomsa neighbours (Amoak Adum, Abuuk, Ansoateng, Akaayaabisa, Aleeti, who represented his brother Asuebisa, Ayuekanbe, Afelibiik Abuumi, Anyik, and, later, one of Atupoak’s sons). Anamogsi was in the kusung only on the first day, but he had to provide all the food, drinks, and other supplies. The men in the kusung asked him if everything was ready.

Aduedem 2019:14: When the ko-bisa and other people gathered on that day, the sons or relatives prepared three calabashes of zo-nyiam, three calabashes of groundnuts, and drinks (three bottles of akpeteshi). They gave a calabash of zo-nyiam and groundnuts and a bottle of the drink to the elders (both yie-nyam and ko-bisa) in the kusung and to the women inside the dabiak.

4.2.1.3 Showing the millet beer produced

Anyenangdu’s Kumsa, 3 March 1991: Anamogsi showed the elders three pots of pito (one for Anyenangdu, two for the other funerals) to show that all preparations had been completed.

4.2.1.4 Weapons are brought to the granary

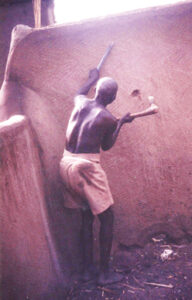

Anamogsi preparing the weapons in the ancestral room

Anyenangdu’s Kumsa: 3 March 1991, around 9.00 am: Anamogsi prepared the weapons (bows and quivers with medicine) of his father, Anyenangdu, in the dalong (kpilima dok).

Later an axe (liak) and a battle axe (kpaani) were added to the objects near the granary.

Awuliimba’s funeral, Sandema-Kalijiisa-Anuryeri (fn 88,223b): After carrying the mats out to the cattle yard, Awuliimba’s eldest son fetched the deceased’s bow and quiver from the ancestral room and walked with them to the central granary in the cattle yard, where he fastened the weapons to one side.

Funeral at Agbain Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa (fn 01,3a): On the afternoon of the second day, the following things were at or near the granary: one quiver, one bow, many calabashes, one metal trunk, and one trunk with clothes of the dead.

4.2.1.5 Entertaining guests in the kusung with millet beer

4.2.1.6 Signalling the start of the celebration with a firecracker shot

4.2.1.7 Closing the central granary (bui lika)

Anyenangdu’s Kumsa (fn 94,87b; 97,51a; 9763b*): The upper opening of the central granary was [halfway] closed (bui lika) on the first day of the Kumsa funeral after the first song (yiili) and was reopened (bui laka) at the end of the fourth day (gbanta dai).

4.2.1.8 The elders, singing kum yiila, dance to the granary (on several days)

Anyenangdu’s Kumsa: The elders danced to the granary (bui) of the deceased and back to the kusung dok. They sang funeral songs (kum yiila).

Singing Elders move to the granary (Guuta)

Funeral at Adiita Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa-Guuta: The elders paraded four times from the kusung dok to the bui (at 2.35 p.m., 3.44 p.m., 4.07 p.m., and 4.48 p.m.); each procession lasted about five minutes. The men’s group’s lead singer and musical leader was Akanbong, who is from another Guuta compound.

Funeral at Asebkame Yeri, Wiaga-Chiok (fn 88,120b): On the gbanta dai (divination day), the dirges had to be cancelled – there were not enough singers as, in Sandema, the Agric Show was on the same day.

Yaw (fn 97,19b), regarding the kum yiila of the men: The lead singer is chosen by the men in the kusung dok at the planning stage (before the funeral celebration begins). They usually choose the eldest, who hands over the position to the best singer in the group. After the initial intonation, a second unnamed singer spontaneously joins in. If no one repeats the first verse, the first singer will have problems. The first and second singers sing the same phrase, but the first one sings louder.

Danlardy Leander (fn 94,86*): The elders’ processions take place on the first, second, and fourth days.

U. Blanc (2000: 138): While the men sing their first four kum yiila, the women are not allowed to lament or sing, nor should musical instruments be played.

Aduedem (2019: 14): A male singer intones the funeral song at the main entrance, and all join in the chorus and move to the mat and back again. He intones the song once again, and everyone joins; they enter the kraal again and back outside. After the second singing, the sons bring a fowl, saying: ‘We are giving this to our father.’

Azognab (2020: 43) (Information from Anab Anakansa, Sandema): The traditional status of the deceased before his or her death determines whether ginggana nakka (beating of cylindrical drums) should accompany the dirges of the men or not. [Men begin singing] the dirges before the women.

p. 43f.: …dirges [are sung] around the house if the deceased persons are women, landlords or chiefs. For the funerals of ordinary men, the men’s dirges are sung from outside into the cattle yard and back up and down before the nang-foba.

4.2.1.9 Zong zuk cheka drumming on the flat roof

Drummers on the flat roof (Anyenangdu Yeri), 1991

Anyenangdu’s Kumsa, 3 March 1991 after 2.30 p.m.: Musicians played the drums on the flat roof to the left of the main entrance. The dunduning drum and the sinleng double bell were played in the cattle yard.

U. Blanc (2000: 136f and 145): This [drumming] and firecrackers are used to announce the beginning of the funeral celebration (darika, ‘proclamation’) to the neighbouring sections. The intonation of these rhythms outside the funeral celebration is considered taboo (kisuk).

4.2.1.10 Naapierik ginggana (‘war dance-like dance’)

Naapierik ginggana in Anyenangdu Yeri, 1991

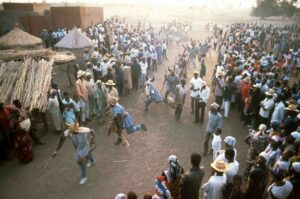

Anyenangdu’s Kumsa, 3 March 1991, after 2.30 p.m.: Dancing towards the tampoi, men from Badomsa performed a war dance-like dance with simple sticks. This group of men was comprised of Akansuenum (Asisapo Yeri), Aparik-moak (Aparik Yeri), Bawa (Akpeedem Yeri), Atupoakbil (Angoong Yeri), and Abui (Aniok Yeri). The first of each dance phase to reach the tampoi left the group.

Godfrey Achaw (fn 73,47b): [F.K.: Is nagela here identical to naapierik ginggana?] Nagela dances are performed at the rubbish heap. Although the nagela dance is usually not danced by women, here, men and women dance in mixed groups of two, one behind the other. There is a hole in the tampoi. Before someone starts dancing, they put some money in this hole. It is intended for the musicians. All relatives of the deceased must dance or at least give some money. The male or female chief mourners may kill a live chicken at the hole and then throw it in. After this dance, the distribution of gifts begins (see siinika).

U. Blanc (2000: 137): Some informants place the naapierik ginggana ritual immediately after the zong zuk cheka and others after the burning of the mats (tiak juka).

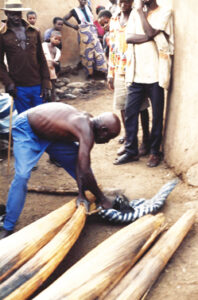

4.2.1.11 More death mats are collected from neighbouring compounds

Two death mats are taken from Atinang Yeri.

Anyenangdu’s Kumsa, 3 March 1991, 3.30 p.m.: Aboali (Atinang Yeri), Asie, and the gravediggers Adok and Akpeedem went to the neighbouring Atinang Yeri to fetch the mats for two more funerals (‘ngari kumu ta jam’). Ali Amuning (the younger full brother of Atinang) and Awogmi (Angmarisi’s son). Anyavoinbey from Awala Yeri carried a bow and quiver; Apintiiklie from Aninama Yeri carried 2–3 calabashes. The two dead people from Atinang Yeri were included in Anyenangdu’s funeral celebration.

Funeral at Adiita Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa-Guuta. At 2.48 p.m., almost the entire funeral party (except the elders in the kusung dok) moved to Awusumkong Yeri (also Guuta), about one kilometre away, to collect the mat of a related deceased man. The mat, two bows, a quiver, and a cloth bag with the cloth for the mat were carried to Adiita Yeri by gravediggers and placed there at the bui. Five other mats were also taken from Awusumkong Yeri but were not funeral mats. These mats were gifts and were thus not carried by gravediggers.

4.2.1.12 The eldest son and the impersonator put on the deceased man’s clothes.

Anyenangdu’s Kumsa (fn 94,22a), 3.3.91, 16.00: Anamogsi, the eldest son of the deceased Anyenangdu, put on his clothes. This action cancelled a taboo that had existed since Anyenangdu’s death [endnote 73]. Imitator Agoalie put on these clothes immediately afterwards.

4.2.1.13 Shooting arrows

Anyenangdu’s Kumsa, 3 March 1991, around 4.00 p.m.: After Anyenangdu’s eldest son and the impersonator were dressed, an arrow (pein) was shot into the bush (uncultivated land).

F.K.: I have not heard of this custom anywhere else nor received any reason for it.

4.2.1.14 The widows go to the death mat at the granary

Funeral at Adiita Yeri, Wiaga-Guuta (I was only permitted to observe this ritual in Guuta; no photos were allowed there): The widows went to the death mat at the granary. I saw a widow touch the mat (of her deceased husband?) three times.

4.2.1.15 Sinsan-guli chants (women singing to the accompaniment of basket rattles)

These chants occur on the first and second days. Notably, they are still performed on the fourth day in Wiaga-Sinyangsa and Yisobsa but not in Wiaga-Chiok. U. Blanc writes that, according to some information, the sinsan-gula are no longer played on the fourth day.

Funeral at Akadem Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa (fn 88,200a+b), 31 January 1989: At noon on the funeral’s gbanta dai, women also sang and beat sinsan-guli rattles at the dressed granary (bui).

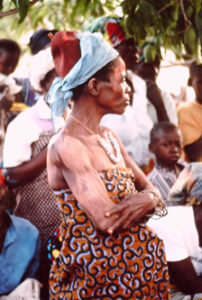

Funeral at Acha Yeri, Sandema-Chariba (fn 88,221b + 223b); on 5 March 1989 (gbanta dai): In the cattle yard, a hut was erected of millet stalks and left open at the sides. Women from Chana were sitting under it, rattling in front of the straw mats. Their leader (and pre-singer) was Akututera (Ayanaab’s Kasena wife), who married in Badomsa. A busik basket was available for donations. On the thatched roof were bundles of millet seeds.

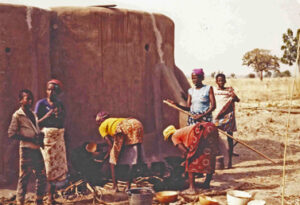

Sinsan-gula women in Sandema-Choabisa

Funeral at Atekoba Yeri, Sandema-Choabisa (fn 73,61): The death mat was lying in the cattle yard, and the singing sinsan-gula women were sitting around it. On the mat of the dead man were his zu-kpaglik (neck support) and horsetail fly whisk. The dead man’s clothes and red cap were hanging on the granary; next to them was a wooden chest studded with cowries and holding the dead man’s calabash helmet and other things.

Funeral at Adiita Yeri, Wiaga-Guuta (fn 2008, 15b): After the widows had moved to the mat at the granary, women with small, black sinsan-gula rattles situated themselves around it. Their leader was Ayomalie’s mother.

Awuliimba’s funeral, Sandema-Kalijiisa (fn 88,225b), 9 March 1989: On the gbanta dai, the leader, Akututera (a Kasena wife in Kalijiisa), complained that all the income (of the sinsan-gula women) had gone to the Bilinsa women. She would have agreed to one-quarter of the income for the Kalijiisa women. Besides, the Kalijiisa women had already participated in the fresh funeral.

Yaw (fn 97,19b), regarding the sinsan-gula yiila: A female lead singer begins (Yeri), a second woman alone takes over the next line, and then everyone joins in. Sometimes, there are also three lead singers or one lead singer sings the first line alone twice. The sinsan-gula women choose the lead singer at the beginning of the funeral celebration. She is usually the eldest and can pass this task on to another woman. The second singer is not appointed.

U. Blanc (2000: 138): The women begin their funeral songs after the zong zuk cheka at the death mat in the cattle yard. The songs consist of alternating singing by one or two lead singers and the choir. They are constantly accompanied by sinsan-gula rattles.

E. Atuick 2020: 72–73 (on the fourth day after the kusung visit [of the impersonator with the sinsan-gula women]): After spending some time in the kusung, the leader rises and goes back into the compound amid singing and dancing by her and her entourage. As soon as they go inside the compound, they continue the singing of dirges, some of which contain insults and words of mockery directed at the men. In one of the songs [that] I heard while observing the ritual performance, the lyrics contain the following lines:

I am going to get a dog instead of giving birth to men, who will not stay at home but run off with women while hunger kills us. If they are not running away with women, they are probably drunk and lying in a gutter somewhere along the road. Is it not better to have a dog as a puppy instead of giving birth to misfortunes as children?

Thus, through the singing of songs, Bulsa women have the licence to direct words of criticism, mockery, and vulgar insults at their men without getting into trouble, although the men do not countenance such behaviour in ordinary times. Bulsa culture frowns upon women talking back at men or openly criticising them in public, but occasions such as funerals provide women [with] opportunities to openly criticise or take on [confront?] the men through music and other means. It was, therefore, not surprising that I heard many songs in which the women criticised, mocked, or insulted the men during my observation of the rites.

While the singing continues, the men, led by the chibouk in charge of the funeral, gather an animal, millet, sorghum, and drinks (especially pito, a beer made from sorghum or millet). Millet flour is mixed with plenty of water in a giant calabash and presented to the women. [A spell is cast] on any witch or wizard who might want to poison these things. The animal and foodstuffs are meant for the preparation of ritual food, while the drinks and flour in water are for the refreshment of the women who sat throughout the night preparing funeral meals and mourning the deceased by singing dirges.

4.2.1.16 Cherika or cheri-deka (imitation)

These dramatic scenes can occur on the first, second, and fourth days. A deceased male is usually imitated by one of his sons’ wives. This woman’s choice depends on her genealogical position as well as her acting skills, as she must perform short impromptu episodes from the deceased’s life.

Anyenangdu Yeri: Agoalie imitating Anyenangdu, her father-in-law, 1991

Anyenangdu’s Kumsa: Blind Anyenangdu was imitated by Agoalie, his daughter-in-law, who made her way through the crowds with Anyenangdu’s iron walking stick. She was wearing Anyenangdu’s clothes and his hat and moved with the sinsan-guli women through the compound to the kusung dok. There, she sat down with the elders (Danlardy: ‘Ba ta yeri-nyono a nyini a pa te kusung dema’). According to Danlardy, the conversation began with the following question to the elders: ‘Why are you here in this compound?’ They replied, ‘Anyenangdu died, and we are here to hold his funeral’. After more questions and answers, the impersonator and her companions returned to the compound, where they sat down near Anyenangdu’s granary. Anamogsi gave them a bottle of akpeteshi, a pot of millet beer and two large calabashes of millet water.

Agoalie (= Anyenangdu) in the kusung dok with the elders

Awuliimba’s funeral, Sandema-Kalijiisa (fn 88,225b) 9 March 1989 (before the killing of the donkey): The wife of Awuliimba’s eldest son imitated the dead man. She was wearing a man’s smock, sat down in the kusung, and demanded kola nuts, which she buried in the ground so that no one else could find them. She was addressed as Awuliimba. Later, a second woman in a male costume arrived. She imitated one of Awuliimba’s sons, who died in 1987 and whose Kumsa had already been held.

In another scene, Awuliimba’s imitator pacified a screaming woman who wanted to return to her parents because her husband had beaten her. She (as Awuliimba) tried to comfort her and keep her in the house. Apart from Awuliimba’s impersonator, his elder daughters and his brother’s daughters also wore male smocks.

Funeral at Agaab Yeri (fn 08,15b) Wiaga-Yisobsa-Chantiinsa, 17 February 2008: The impersonator was wearing a man’s clothes and a straw hat.

Scenes played at 9.19, 11.53, and 11.58 a.m.: As the deceased man had been very argumentative, the impersonator involved other men and women in fights and verbal arguments.

Agaab Yeri: The impersonator scuffling with an adversary of the deceased man

The imitator (left) at Agaab Yeri

Funeral in Sichaasa, Wiaga (fn 88, 185b), 19 January 1989: On the second day (tika dai), the impersonator of the deceased women was the eldest woman of the house. Like the deceased during her lifetime, the impersonator wore only leaf clothes and carried an empty busik basket on her head.

Funeral at Adiita Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa-Guuta (fn 08,15b), 22 February 2008: Only after burning the mats at around 6 p.m. on the first day (kalika) did the impersonator visit the kusung dok and talk to the elders there. She rolled cigarettes and smoked. Outside, she engaged in an agitated discussion with another woman.

Funeral at Atinang Yeri, 27 January 2006, Wiaga-Badomsa: Atinang’s impersonator was Atakabalie, the wife of his son Anyik. Atinang’s brother, Angmarisi, was imitated by another woman whose name Yaw cannot remember. Agoalie was imitated by Ajadoklie (daughter-in-law of Agoalie’s co-wife Agbiera). The unmarried Kweku was considered a child (biik) and was not imitated.

Robert Asekabta, regarding the term cheri: Cheri denotes simply the activities, behaviours, and attitudes of the person whose funeral is being performed. Cheri-deka is normally performed in the case of an elderly person; the person who performs this function is typically the wife of the deceased’s son or his brother’s son’s wife.

The che-lie [Atuick: cheri-deiroa, meaning ‘impersonator of a deceased person’] is usually responsible for the following duties:

(1) Taking the mat(s) to the granary (bui); (2) Brewing the pito near the bui; (3) Supervising the shea butter extraction from the shea nuts; (4) Boiling the beans; (5) Boiling the bitter pito (da-tuek); (6) Smearing all the children and grandchildren of the deceased, his brothers and cousins, etc., with red laterite clay-paint.

In other words, the che-lie acts as the manager of the funeral in the nangkpieng (cattle yard).

Margaret Arnheim, Gbedema (fn M28a and 34b): Actions of impersonators are not bound to gender. They are often determined while the person is still alive if it is seen that someone can imitate the deceased well. It does not have to be a specific relative. Another woman usually imitates a dead woman; a man usually imitates a dead man.

(fn M37a): The female impersonator would wear the dead man’s red cap if the dead man was older and wore such a cap. It is said: ‘Wa vug wa zutok’ (‘She [the impersonator] wears [literally ‘covers’] his red cap’). For example, if a small child led the deceased during his lifetime, the same child would lead the impersonator.

Leander Amoak (fn 81,28a): In the funeral celebrations of both men and women, the impersonator is female. In the case of a man’s funeral, it is a daughter-in-law of the deceased; in the case of a woman’s funeral, it is a relative from her parental home. This woman is also responsible for many other activities; for example, she carries the baskets outside and paints relatives with red clay. In the case of Leander’s brother Atiim, it will be his daughter-in-law (Michael’s wife); in the case of Abonwari (a nineteenth-century ancestor), it will be Leander’s first wife, Atigsidum. The woman imitates the dead man without concern for respect: If the dead man was loud, she would constantly shout; if he drank a lot, she would play the drunkard. The Buli name for imitator is che(ri) dieroa.

Danlardy (fn 94,91b*): Che-lieba imitate the dead person. There is no actual meaning of ‘che’.

Yaw (fn 01,2b): Imitation at a worldly feast (tigi) is taboo (kisuk).

U. Blanc (2000: 146): The [imitation] takes place on both the first and second days. As a rule, the impersonator is a daughter-in-law of the male or female deceased. In principle, any relative can take on this role.

Aduedem 2019: 49: The ‘cheri-deka’ is meant to [evoke] vivid memories of the lost soul. It also gives a [sense] of the life lived by the dead person to people who never had the opportunity to know the person in life. The mock play, when done well, especially by a spectacular person, could attract much attention and give colour to the celebration. In all of them, people are reminded of the dead person’s life and how the person would be missed. Others, too, get to know how the dead person once lived his life.

Adumpo Emile Akangoa, Facebook group Buluk Kaniak, March 29, 2019: Although globalization has had a toll on the cohesion of our extended family system, funerals are still being communally performed in Buluk. Cheri-deka must not necessarily be done by daughters-in-law in the nuclear family. Whenever no daughter-in-law in the nuclear family plays that role, they get somebody from the extended family to do it.

Azognab 2020: 49 (Information from Akaalie Aginteba, Sandema 2018): The name of the meal [cheri saab] is carved from the cheri-dierowa (a daughter-in-law of the deceased who imitates and acts like him or her during the funeral). The cheri-dierowa wears the deceased’s clothing and acts like they did when they were alive. She does this from the beginning of the kuub-Kumsa to the end. Usually, the imitation [recalls] the past good and bad character of the deceased. It is often claimed that the spirit of the deceased person in question could possess the ‘imitator’ (cheri-dierowa) to portray the exact character of the deceased during the funeral.

The significance of the cheri-deka (…imitating and acting out the deceased’s lifestyle…) is that it reminds the community about the deceased’s past character, whether good or bad [endnote 74]. The cheri-deka, therefore, serves as a lesson for the living, who may endeavour to lead good lives so their cheri-deka will be praiseworthy.

p. 45: Every Bulsa funeral has personnel who are directly in charge of the whole ritual apart from the elders in the kusung dok …This [group] usually comprises the yeri-lieba (meaning ‘daughters of the house’) if the deceased was a man or the che-lieba (married women in the family lineage, who hail from the same village or town where the deceased hailed from) if the deceased person was a woman.

E. Atuick 2020

Evans Atuick wrote his MA thesis on how women participate in funeral rituals: ‘Women, agency, and power relations in funeral rituals: A study of the Cheri-Deka ritual among the Bulsa of Northern Ghana’.

This thesis is the most comprehensive account of the cheri-deka ritual to date. Other rituals are also included and described by Atuick in the correct order. Therefore, the description of the cheri-deka and the cheri-deiroa (Atuick, pp. 67–99) will be reproduced here in only a slightly abridged form. Notably, the day in the first funeral celebration during which certain partial rituals are performed is not always clear in this work.

Atuick p. 65: Ideally, the wife of the first son of a Bulsa man or woman must play the role [of the cheri-deiroa]…

p. 67ff: …the cheri-deka ritual commences on the second day of the kuub-kumka, when the ta-pili… is discarded [after the war dances (leelika)]… The cheri-deiroa [che-dieroa] is told by the chilie [female master of ceremonies for the funeral] to dress up in her father’s tangkalung… if the deceased was a man… But if the deceased were female, she would be told to put on leaves, pick her mother’s sapiri… and busik and go out. In the case of a deceased male, she must join the men for the leelika [war dance] around the compound three times; in the case of a deceased female, she must… dance along as they play the drums around the compound four times. When these ritual dances are over, the cheri-deiroa can disrobe… and perform her normal chores. … However … the deceased persons’ [relatives] will engage with her similarly [F.K.: mockingly?].

On the kpaata dai…the cheri-deiroa must be the first person to start the fire used for cooking the beans… She cracks the first shea nut… [F.K.: See the section on kpaata dai, 4.3.4.1].

…Meanwhile, when the men are sharing their share of the cheri-deka meat [F.K.: on the fourth day of the Kumsa celebration], they will call the cheri-deiroa and give her the chest of the animal, [which] is usually reserved for landlords. This symbolises her status as a landlord during her performance as the living copy of [a] deceased elderly [man]. After taking her share of the meat, she goes in search of the deceased’s sons-in-law, who are there to mourn their parent-in-law. She will play with or talk nicely to sons-in-law who were on good terms with the deceased person before dying but will attack others who were never on good terms with him or her. She does similar things to friends and other relatives of the deceased, treating each as her deceased parent-in-law would have dealt with them in his or her lifetime. In return, understanding the game, they [the addressed or insulted people] play along and even give her money or other gifts [that] they used to give to the deceased in his or her lifetime on earth as a way of appeasing the soul of their parent-in-law, friend, or relative.

Moreover, on this final day [of the Kumsa], the deceased’s grave is plastered as part of the funeral rites, and the cheri-deiroa again plays a role. The male chibouk who is leading the funeral will send a message to the female chilie to send the cheri-deiroa to them to help put the grave in shape.

A Bulsa family may perform the kuub-juka rites immediately after the end of the kuub-kumka celebration. In this case, the cheri-deiroa has no break in the performance of her impersonator role but will continue for the next four days throughout the Juka rites until the end. However, [in cases when] the Juka rites are postponed to a future date, be it months or years, the cheri-deiroa can keep her role in abeyance until the family is ready before resuming her duties and responsibilities to make the funeral successful.

[F.K.: The following text refers to the bogsika dai, which often occurs before the first day or on the first day of the Juka funeral:] The kuub-juka rites typically start with a journey to the maternal uncle’s compound of a deceased man or the paternal compound of a deceased woman for two main reasons: to collect things for the performance of the final rites, and to inform them about the intention to dispatch the restless soul of the deceased to the land of the dead, where he or she will find lasting, peaceful rest among his or her forebears. The cheri-deiroa must dress up in the deceased’s clothing and animal skin, carry his walking stick, etc., if he was a man or carry her basket and food stick if she was a woman and follow the travelling team to the deceased’s compound. The travelling team [to the compound of a deceased man’s maternal uncle] usually includes the children of the deceased, one or two of their relatives, the cheri-deiroa, and her female escort(s). The travelling team that goes to a deceased woman’s paternal compound includes her children, the san-yigmoa [her marriage intermediary], one or two relatives, the cheri-deiroa, and her female escort(s).

As soon as they arrive at the compound, the cheri-deiroa continues her role as an impersonator of the deceased by reenacting the same kind of interaction that [the person] had with his or her relatives [while] alive and [when visiting] them. She will play with those she knows the deceased had good relations with and attack others that he or she disliked while alive. Some of these people who fully understand the game of cheri-deka will immediately engage the cheri-deiroa in the same manner [in which] they dealt with the deceased [immediately when] she appears at the compound in the deceased’s apparel. She must equally respond to their acts or speeches as if she were the deceased person who is still alive and interacting with them.

While this is going on, the delegation enters the compound and sends for the elders to inform them about their mission. The leader of the delegation, speaking on behalf of the rest, exchanges pleasantries with the elders and says to them, ‘Your son (or daughter) wants to go home, and that is why I have come to inform you before giving him/her permission to go home and rest.’ After this, the delegation is fed and refreshed by the family before rising up to start their compound-to-compound rounds within the lineage [to collect] foodstuffs, especially millet and sorghum, as well as guinea fowl and other domesticated fowl that they can catch or kill. [To collect these foodstuffs and birds] during this compound-to-compound journey, the delegation will visit every compound on the maternal side of a deceased man’s lineage or the paternal side of the deceased woman’s lineage… The cheri-deiroa, just like her late parent-in-law used to do, has a licence to play with any of her uncles by catching any livestock that belong to him without any resistance. Hence, with the assistance of her team, she can catch and kill as many birds as she can, as long as the birds are found in any of the compounds in the paternal lineage of the parent-in-law she is impersonating. After they have covered every compound within the lineage, collecting everything they need to collect, they will return to the original compound the deceased is related to or hails from. By the time they arrive there, there is enough food and drink for them to feast, after which all the households of men within that compound will contribute their share of foodstuffs and birds to add to whatever they have collected from neighbouring homes before returning home.

(p. 81) …The final rites of a man’s funeral occur on the fourth day [of the Juka] when the louk [lok] is broken in the middle of the compound’s yard. The cheri-deiroa has a role to play here. She must be present when the birds collected from the deceased [man’s] mother’s compound are dedicated to the spirit of [the] deceased man’s louk before it is broken and shattered in the main yard of the compound…Following the war dancing, the eldest son of the deceased performs the final sacrifice of the rites on the left wall of the main entrance… While standing there, he gathers all the live fowls brought from the earlier visit to his late father’s mother’s lineage and those donated by friends and sympathisers to help him complete his father’s funeral rites and sacrifice them on the wall. He does this by hitting the fowl, one by one, against the wall to die. While their blood flows down the wall, he says, ‘Ba ko parik! Ti kowa kumu yai nueri kama!’ [‘They have killed a wall! Our father’s funeral is now over!’]. This sacrifice marks the end of the funeral rites for the deceased man and, by extension, the role of the cheri-deiroa. The next thing [to be done] is for all the dead birds to be plucked and cooked for all present, including the cheri-deiroa to eat to their satisfaction before dispersing.

However, the Juka rites of a woman are much more complex, with the cheri-deiroa playing a much more influential role. In this case, women from the paternal home of the deceased mother-in-law must arrive on the evening of the third day of the rites to sleep over. They usually come with their own puuk (a ball-like object made from certain leaves [endnote 75] that symbolises a woman’s womb during funeral performances) to participate in the rites. As a group, the wives in the compound must acquire a puuk for the rites to commence. The cheri-deiroa must also acquire a puuk for the rites. The next morning, on the fourth and final day of the rites, the visiting women will take their puuk to the san-yigmoa’s compound, [handing] it over to him and [asking] him to help them present it to their sisters’ husbands. The san-yigmoa then leads them to the compound where the deceased lived, exchanges pleasantries with the elders, and hands over the puuk to them…

At the same time, women in the funeral compound are also preparing food that must remain on fire until those returning with the puuk and food from the san-yigmoa’s compound stand apart from the compound and send for the women inside to come and meet them. As soon as they get the message, the chilie will [ensure that] drinks, flour mixed with plenty of water, and saab [are] made ready for them to take along for those waiting outside. On meeting them, the women from the funeral compound and the cheri-deiroa will serve those waiting with the food and drinks they came with and collect the puuk and food brought from the san-yigmoa’s compound to take back inside the funeral compound.

The following day, all three puusa [plural of puuk] are taken back to the same spot where the women met the previous day and broken into pieces, except for the puuk provided by women of the deceased person’s compound, which is handed over to the cheri-deiroa for keeping. Thus, the puuk provided by the women from the deceased’s paternal home and the one provided by the cheri-deiroa are both destroyed, but the chilie presents the one from the wives from the compound sponsoring the funeral to the cheri-deiroa as an inheritance from her deceased mother-in-law. As the eldest son’s wife, the cheri-deiroa receives this puuk as the rightful inheritor of the deceased’s household and property, and she is expected to keep this until her demise. The Juka rites – and, by extension, the cheri-deiroa’s role – are finally completed when the compound elders kill and present an animal – usually a goat or sheep – to the deceased woman’s paternal relatives who had brought the puuk, which they take home.

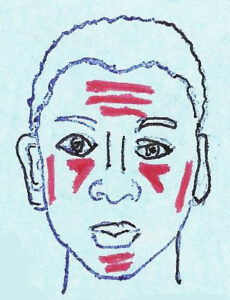

4.2.1.17 Ritual treatment of relatives: hand rope or scarve, red cap, nabiin-soruk necklace, bell, painting with daluk clay

Applying cords and headscarves for wrapping around wrists is possible on all funeral days and times. A distinction should be made here: on the one hand are short knits (boom or buoom) and headscarves, which are placed around hands, and which are a symbol of friendship; on the other hand there are long knits, which are only put on close relatives of the deceased (‘to prevent suicide’).

Funeral at Adiita Yeri, Wiaga-Guuta (fn 2008,15b), 21 February 2008: On the first day at 5 p.m., a man appeared with a bundle of braided hand ropes, which he distributed. All children and other very close relatives received a rope for their left hands (followed by the painting and donning of the nabiin-soruk chain).

Awuliimba’s funeral, Sandema-Kalijiisa (fn 88,224a+b), 8 March 1989: On the second day, the women on the mat wove buoom strings. Originally, a piece of cloth was only wrapped (boblik) by the nong around the hand of his or her girlfriend or boyfriend. By contrast, in the case of the German guests Barbara Meier and Annette Schierwater, this was also done by a woman (Akututera?). On the gbanta day, the recipients returned the scarf to the giver with the money they had received and a surcharge.

9 March 1989 (fn 88,225b): After divining, the buoom strings that had been worn around wrists were placed next to the granary, and the widow’s strings were thrown over the nang-gaang wall.

Funeral at Asebkame Yeri, Wiaga-Chiok (fn 88,119b), gbanta dai, 6 December 1988, 1.15 p.m.: A lengthy, braided buoom rope (over one metre long) was wrapped around a fully dressed woman’s left hand in the cattle yard, in front of two chests containing the dead man’s personal belongings. She pulled the two existing and shorter knits on her hands up her arms. She was also given a nabiin-soruk necklace and a tall red cap. Her arms, legs, and face were smeared with red junung or daluk clay.