5 THE (KUUB- ) JUKA OR NGOMSIKA FUNERAL CELEBRATION

5.1 Introduction

5.1.1 Juka celebrations attended by the author

I (F.K.), the author of this work, attended two Juka celebrations myself; my assistants Danlardy Leander and Adama collected information about another celebration in Chiok (May 1990). An important additional source of information was the description by Joseph Aduedem (detailed 2019 and abridged 2020: 54–61), which he prepared based on an interview with his grandfather, Alanjo Aduedem (Sandema-Bilinsa), and papers written by F.A. Azognab and published in 2019 and 2020.

1) The Juka funeral in Wiaga-Mutuensa (Ajuzong or Ajuyong Yeri, 24–27 April 1989) was held for a deceased diviner. I took part in the cheesika/bogsika (24 April, fn 88,270) and the lokta juka dai (fn 88.270+272; 27 April).

2) A Juka funeral celebration in Wiaga-Yisobsa was held for the deceased Wiaga chief, Asiuk, on 6–12 July 1994. I attended it on the sira manika dai (9 July, fn 94,14+15a). On 10 July (the lokta juka dai), Danlardy photographed the rites on my behalf and collected information.

3) In Wiaga-Chiok (May 1990, fn 88,305b), my helpers Danlardy and Adama took photos and collected data on the senlengsa dai.

5.1.2 Further information about the Juka

Names: Juka means ‘burning’ (the quiver, etc.); according to J. Agalic et al., kuub juka means ‘burning the funeral’; ngomsika means ‘scratching’. I could not find a plausible explanation for this name.

Timing and significance: Although the Juka celebration enables the deceased to enter the realm of the dead (kpilung), there does not seem to be any great haste in holding this celebration compared to the Kumsa. Indeed, many years often separate the Kumsa and Juka. One reason for this relative lack of urgency may be that the temporary successors of the deceased, such as his eldest brother or son, want to keep their acquired social position (e.g., as a kpagi) and the shrines, land, and cattle connected with it. After the Juka, however, they must hand everything over to the real inheritor according to genealogical position (see Kröger 1982 and 2003).

A major disadvantage of a long postponement of the Juka would be that women of childbearing age would also have to wait a long time for remarriage. Nowadays, however, widows are allowed to have a new relationship. It is given official status on the third day of the Juka when the widow officially chooses her partner (see 5.2.4.7).

Margaret Arnheim (fn M28a): Only through the Juka/Ngomsika celebration does one become an ancestor. The Juka is not performed for the last-born son or daughter, but he (she) still becomes an ancestor.

If only the Kumsa funeral were completed, it is said that only one half was celebrated (‘nye kuub zaani’).

U. Blanc (2000: 221): Overall, the variety of musical performances of the Kumsa funeral celebration is not [equal to that at the Juka].

Aduedem (2020: 54): This part of the funeral celebration takes four days… In the case of a man of status (kpagi) who was also a yeri nyono and had sacrificed to great ancestral gods, it takes six days [F.K.: This information is unconfirmed for Wiaga].

5.2 Chronological listing of the ritual events

Preliminary remarks: The names of the feast days and the distribution of the events on the various days do not seem to be wholly fixed, even within a single village. As such, in the compound of Chief Asiuk, the important rites of burning the quivers and destroying the pots were not performed on the third day. This day is usually called the lok tuilika (turning of the quiver) or sira manika dai. Instead, these were performed on the fourth day, which is then called the lokta juka dai. In Mutuensa, the quivers and pots were destroyed on the third day. If the weapons are burnt on the third day, then the fourth day is called the senlengsa dai.

Cheesika: A Mutuensa group has collected food in Chiok.

Cheesika in Chiok: The Mutuensa impersonator

5.2.0 Previous day: Cheesika (collecting) or (loan word Twi) Bogsika (endnote 96a)

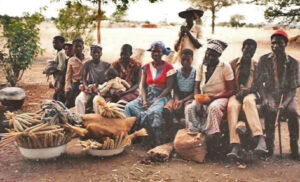

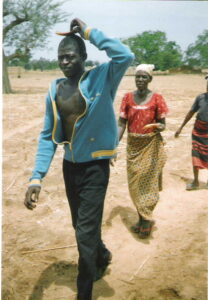

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Wiaga-Mutuensa (fn 88,270a), 24 April 1989: Concurrently or overlapping with activities in the house of the deceased, a group consisting mainly of women – including the widow from Ajusong Yeri – collected food for the celebration in all compounds of the deceased’s mother’s section and other houses of this section (in this case, Chiok). The female impersonator, clad in a long coat and tangkalung apron, and a man carrying the deceased’s bow and quiver with arrows accompanied the group (see photo). The photo shows baskets and bowls of millet and chickens as gifts.

Yaw (fn 08,112b): They collect, for example, millet or sprouted millet (for the kpaam ngabika of the following day). Only women give donations directly. A man may ask his wife to give his share.

Aduedem (2019: 23; revised): [According to Aduedem, these begging visits take place in Sandema on the first day, kpaama ngabika]. Then, they call the widow and ask her to go and beg for resources to perform the final funeral rites for her husband. This begging symbolises the dependence of the widow on the generosity of society [her own lineage?]. She could go to one house in the morning, one in the [early] afternoon and one in the late afternoon. In any of these three rounds, when she gets to a house, the men will give her zaa (millet) while the women could give her ingredients, shea nuts, etc. When she has taken enough rest after the third round, she goes to her san-yigma’s (link man’s, intermediary’s) house. He takes her to a diviner (baanoa) and divines for her. They will both return to the san-yigma’s house, and the san-yigma’s wife will prepare TZ [Buli saab, or millet porridge] for her to eat. The san-yigma then brings her back in the night, by which time they would have ground the kpaama (pito malt) [while] waiting for her to come, [after which] they put the malt flour (kpaam-zom) [in] water.

Azognab (2020: 50), information via Atombil Andoagelik of Sandema in 2018: [According to Azognab, these begging walks take place on the first day, the kpaama ngabika dai]. This [the first funeral day] is also the day the pikogi (widow) is made to go around the community to beg for food items such as millet, beans, groundnuts, and others if the deceased person was a married man.

Atuick (2020: 89): [On the first day,] the kuub juka rites normally start with a journey to the maternal uncle’s compound or the paternal compound of a deceased woman for two main reasons: to collect things for the performance of the final rites… The cheri-deiroa [imitator] must dress up in the deceased’s clothing and animal skin, carry his walking stick, etc., if he was a man or her basket and food stick if she was a woman [while following] the travelling team to the deceased’s compound. The travelling team to a deceased man’s maternal uncle’s compound usually includes children of the deceased, one or two of their kinsmen, the cheri-deiroa, and her female escort(s). The travelling team that goes to a deceased woman’s paternal compound includes her children, the san-yigma [her marriage intermediary], one or two kinsmen, the cheri-deiroa, and her female escort(s). As soon as they arrive at the compound, the cheri-deiroa continues her role as impersonator of the deceased…

While this is going on, the delegation enters the compound and sends for the elders to inform them about their mission. The leader of the delegation, speaking on behalf of the rest, exchanges pleasantries with the elders and says to them, ‘Your son (or daughter) wants to go home, and that is why I have come to inform you before giving him (or her) permission to go home and rest.’ After this, the delegation is fed and refreshed by the family before rising up to start their compound-to-compound rounds within the lineage [to collect] foodstuffs, especially millet and sorghum, as well as guinea fowl and other domesticated fowl that they can catch or kill. During this compound-to-compound journey, the delegation will visit every compound on the maternal side of a deceased man’s lineage (or the paternal side of a deceased woman’s lineage) [to collect] foodstuffs and birds. The cheri-deiroa, just like her late parent-in-law used to do, [may] play with any of her uncles by catching any livestock that belongs to him without any resistance. Hence, with the assistance of her team, she can catch and kill as many birds as she can, [provided] the birds are found in any of the compounds in the paternal lineage of the parent-in-law she is impersonating. After they have covered every compound within the lineage, collecting everything they need to collect, they will return to the original compound [that] the deceased is related to or hails from.

5.2.1 The first day: Kpaama ngabika dai (preparing malt)

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Wiaga-Mutuensa (fn 88,270–73; F.K. participated). The funeral was held for the following people:

1. a deceased diviner who was married to an Ashanti woman present,

2. Akandetuire, a daughter of Abasitemi Yeri (Badomsa) and who married in Mutuensa,

3. a woman from Atana Yeri (Chiok),

4. a woman from Wiaga-Yisobsa,

5. a ‘daughter of the house’ (yeri lie) who had not died in her husband’s house.

5.2.1.1 Elders in the kusung

Aduedem (2019: 22f): On the first day, every nisomoa and yeri nyono come to the house with millet (zaa) and the woman who ‘sat on the funeral’ (the presiding woman) comes to sit with the widow (jam kali wa ngaang – [meaning] ‘comes to sit behind her’). When the elders arrive, they sit in the kusung dok as usual with their zaa (millet). The [various types of] zaa are mixed together … and put into two traditional baskets (busiksa). The sons and other relatives provide tobacco (tabi), a fowl and an animal… which are taken [along] with some of the millet from the two baskets to the grave by the gravediggers for the vorup chiesika rituals [Aduedem: ‘chiesi means “to collect”, [referring] to the kobisa bringing millet’. For the rituals at the grave, see 5.2.3.17 and 5.3].

After that, they come to the compound, and the elders thank them. The elders will then call the presiding woman [the chelie or kuum zuk kaliba] to the kusung and give her some of the millet and kpaama (pito malt: germinated guinea corn grains used in the first stage of brewing pito [endnote 97]), [which is provided] by the sons [or other] relatives to grind for them ([the grinding of this millet symbolises the preparation of] pito for [the elders]). When she takes the zaa and the kpaama inside, the sons or other relatives add a good quantity of pito malt that would ostensibly be enough for the funeral celebration…[but] after she has entered, the elders share the rest of the zaa in the two baskets among themselves.

5.2.1.2 Brewing the millet beer and opening (announcing) the celebration

Women brew the pito; it is drunk on the last day when few are present.

Aduedem (2019: 23f): The san-yigma then brings her [the widow] in the night, by which time they would have ground the kpaama (pito malt) [whilst] waiting for her to come before they put the [malt] flour (kpaam-zom) [endnote 98] into water. When the kpaam-zom is kept in water, they announce [the funeral] by shouting: ‘Ba pa baan yuni yooo’ (‘they have taken the diviner’s bag’). This announcement is proclaimed from one house to the next. Then, every relative (especially the sons) will start preparing their pito for the fourth day.

Atuick (2020: 90): Following their return, they must buy or make fermented millet malt [to brew] the kpaam-tiok [pito brewed especially for Juka purposes] to be used for the commencement of the Juka rites. After the malt has been ground in readiness for the brewing of the kpaam-tiok and the date is set for the start of the final rites, a messenger – usually any male kinsman or a san-yigma – is sent to the paternal compound of the deceased man’s mother or that of the deceased woman to invite them to come and join them. [In cases where] the deceased was a man, men from the maternal uncle’s compound may choose to arrive the next day to [drink] the kpaam-tiok or wait until the third day [of] the rites to join them.

5.2.1.3 Guests sleep in the funeral house until the end of the Juka celebration

Aduedem (2019: 24): People start to sleep at the funeral house from that day on (gua kusung).

Azognab (2020: 48): It must be stated that during both the burial and the dry funeral rituals, the men of the community are expected to sleep outside by the funeral house each night as a custom.

5.2.2 The second day: Nyaata soka dai or jueta [or juem] soka dai (the ‘day of the bath’)

5.2.2.1 Welcoming guests and holding speeches (in the afternoon)

5.2.2.2 Preparation of the widows

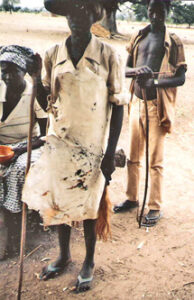

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Wiaga-Mutuensa: There were ten widows (eight from Ajuzong Yeri and two from a neighbouring house in Akabere Yeri?). They either wore leaves at the front and back (often from the nim tree) or leaves at the front and a red fibre apron (vaata; see photo) at the back. In the evening, water was boiled in samoansa pots at the tampoi. A liik (for cold water?), chengsa, and kpalabsa were also used.

Ajuzong Yeri: The bathing place after the bath

Vaata: fibre apron

5.2.2.3 Shaving and bathing widows (not observed)

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Mutuensa (fn 88,270): The widows in leafy clothes were doused with hot water from calabashes, one after the other, according to their ages – first their heads, then their bodies.

I was told that the jom-suiroa woman smeared the widows’ bodies thickly with shea butter to protect them from the hot water. A widow being burnt proves that she was unfaithful to her deceased husband.

The women watching applauded by ululating (in Buli: wuuling or weeling). The following day, there were still large pots (samoansa) as well as a chengsa, kpalabsa, and a liik lying at the tampoi. These had been used for bathing the widows (see photo).

The bating site after the bath

Asiuk’s Juka funeral (fn 94,15a): According to information from Danlardy Leander, water was boiled on the evening of 8 July 1994. The eight widows of Asiuk appeared in leafy costumes. Their bodies were smeared thickly with solid shea butter. Then, the oldest widow squatted at the tampoi, and hot water was poured over her head with a calabash and then over her body. Some women ululated (wuliing). After each of the eight widows had been bathed one at a time, they were led back to their courtyards.

Juka funeral at Anyenangdu Yeri (fn 06,Bf 1a); information from Agoabe (in a letter dated 24 May 2007): The widows’ bath was held at the tampoi. Afulang from Atuiri Yeri and Akanpigma from Adum Yeri organized it. A gaasika was performed before the bath.

Aduedem (2019: 24) (cf. 2020: 55): Towards late evening, a woman [places] water in a clay pot on [a] fire by the rubbish heap (tampoi) outside the house. The widow, surrounded by [other] women, is brought out to sit by the tampoi [as well]. Any widower (whose wife’s final funeral rites have been performed) is called upon, and he comes to shave the widow. When the water (now called juom) starts boiling by night, the women ululate (nag weliing) in jubilation for the water boiling. There is joy because the boiling water [proves that] there is no issue – for when there is a problem, the water will never boil until the issue is [identified through divination] and solved. When the water is boiling, the juem suoroa, a woman traditionally ‘trained’ for that ritual [endnote 99] fetches some of it into a chari [endnote 100], pours some quantity of cold water into it, and bathes the widow, [who is] surrounded by women to form a [human] wall. The widow is smeared with shea butter and daluk, ‘red clay paint’ (laterite [clay] used for ritual painting of the body, e.g., at a funeral… [endnote 101]), before bathing her with the hot water. This ritual bathing is called nyaata soka or juem soka (water bathing) [and is the source of the name (nyaata soka dai) for the second day of the celebration]. It is believed that ‘if the woman is innocent about the death of [her] husband, the hot water will never burn her’.

F.K.: A second head-shaving takes place towards the end of the Juka funerals. See 52.4.8.

Atuick (2020: 90f): The next day is reserved for the widowhood rites, during which wives of the deceased are made to undergo a ritual cleansing bath. From the onset of the funeral rites, wives of the deceased are confined to a room where only a juenseiroa [Aduedem: juem suoroa; woman appointed to care for widows and oversee the performance of their widowhood rites during funerals] has access to them. Only old widows living in a different compound who have not slept with a man since their deceased husband’s funeral rites were completed are qualified to play the role of juenseiroa. The widows cannot eat or touch anything associated with the performance of their husbands’ funerals until they undergo the ritual bath in the evening of the penultimate day of the Juka rites. As a result, only the juenseiroa provides food and water for the widows pending the completion of the ritual to prove that they have not betrayed their late husband by having sex with another man. One of the juenseiroa’s key roles is to prevent men of the compound from getting close enough to be able to touch the widows, which would result in forcing such “contaminated” widows to choose the men who touched them as husbands after the rites.

Early in the morning, the san-yigma who performed the marriage rites [for] each wife must go into the bush with the juenseiroa to harvest leaves for the widows to cover their nakedness before undergoing the ritual bath. After putting on the leaves with ropes around their waists, solid shea butter is smeared all over the bodies of the widows, after which boiling water is poured on each of them three times. It is believed that the hot water will only burn women who have not maintained their purity after the death of their husbands. From my observation, the thick shea butter protects widows from any serious burns from the hot water because [it] is impervious to water. [Therefore], as soon as the hot water is poured on the bodies of widows, it runs down quickly due to the shea butter smeared on their bodies and [thus] does not cause any serious burns.

Azognab (2020: 51–53): As part of the widowhood rites, during the Kuub Juka (wet funeral), the widow is led through the main gate to the back of the house by other women, where she will have the first ritual bath known as the gmanyaksoka [ngmanyak soka]… The gmanyak is identified among the Bulsa [as being conducted] for purification purposes. In the Juka celebration of the funeral, further purification rites for the widow are the zukponika (shaving of the hair) and nyaata soka or jiuam soka (ritual bathing), as explained earlier. I observed that both the shaving and the bathing are done [on] the night of the nyaata soka dai. The rituals take place outside, in front of the house, at the family’s tampoi (ash heap or compost heap), where all the refuse of the household is dumped. In the early part of the evening, the widow is brought out through the main gate of the house, again, with only the vaata (leaves of the shea butter tree or other trees tied together) around her waist and a string tied around her head for the shaving and bathing on the ash heap or compost heap. She is seated at the ash heap or compost heap and is surrounded by a group of women, and while the shaving and the bathing are going on, these women ululate. The [ululation] by the kolieba (married women in the community who hail from the same area as the widow who was married there) [encourages] the widow to bear the heat of the boiled water and [praises] her for her fidelity. This is because the Bulsa [believe] that if the widow stayed morally pure during the widowhood, the water [would] boil easily and that, no matter how hot the water is, [she would] not feel the heat. In other words, the Bulsa believe that if the widow [was] faithful to her husband, the water would not burn her, but if not, she would feel the pain from the hot water. So, the ritual bathing is also a test of the widow’s fidelity. In the ritual process, the widow’s hair is shaved first, [and] then she bathes with warm water boiled in the herbs – [actually, this] boiled water is poured on her; it is done in the full glare of everybody. [Women] form a queue [or wall] around her. Formerly, the widow used to bathe completely naked, but these days, [widows] are often permitted to bathe [while wearing undergarments]. She bathes with really boiling water…

According to the traditional beliefs of the people of Buluk, under no circumstances should a [widow] refuse to go through the ritual during the funeral of her spouse. Unless [a] widow goes through the ritual, she is considered unclean. In the olden days, a spouse was banished from her husband’s home if she refused to go through the widowhood rites. The widowhood rites among the Bulsa can be very humiliating. [Although] they are meant [to ensure] the spiritual separation of the widow from [her] deceased husband and [her] incorporation into society, [such widowhood rituals call] for modification to make [them] more humane and acceptable in contemporary times.

5.2.2.4 Meal of the widow(er)s at the tampoi

Aduedem (2019: 25): After bathing, the juem suoroa prepares TZ and bogta soup with mudfish for the widow, still by the tampoi. She eats that food alone, but any woman whose husband is late and the final funeral rites have been performed can eat that food [as well].

5.2.2.5 Taking the widows to their living quarters

Aduedem (2019: 25): When she has finished eating, the rituals for that day come to an end, and the widow is led inside. She will rub her back against the dalong before [entering] the room to lie down.

According to some information, a widow can choose a husband immediately after undergoing the bath.

5.2.2.6 Biisa lika (closing the female breasts)

Anyiini (an unmarried woman from Anyenangdu Yeri), 1997: If an older married woman has died, her daughters of childbearing age bring a samoaning to the house of mourning. If this ritual is omitted, the milk in the breasts of the childbearing daughter would ‘leak out’ or the breasts would be covered with boils (?).

5.2.2.7 The poali leather arm ring with medicine

Anyiini (Anyenangdu Yeri): On the second day of the Juka, many participants put on a poali leather arm ring with medicine. Some regard it as juju, others ‘just for fun’. This custom exists throughout Bulsaland.

5.2.2.8 Vie cheesika

Azognab (2020: 50; information provided by Atombil Andoagelik of Sandema in 2018): In addition [to the widows’ bath], on this [second] day, every household in the community is expected to bring a basket of millet or sorghum to the funeral house to be shared. This is called vei [vie] cheesika ([literally meaning] ‘contributing to the grave’). Although the millet and sorghum are shared among the elders and the undertakers, it is believed they are for the deceased person as part of preparing him or her for the journey to kpilung (the land of the living dead).

5.2.3 The third day: Sira manika dai (the day of millet porridge preparation) is also called lok tulimka dai or lokta juka dai (the day of burning the quiver) or – at a woman’s funeral – puuta dai (the day of puuk pots)

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Mutuensa: I [F.K.] arrived at the compound with my assistant, Danlardy Leander, at 5.45 a.m. on 27 April 1989.

5.2.3.1 Kpagluk sacrifice (Cf. kpagluk of the Kumsa celebration, 4.2.2.1)

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Wiaga-Mutuensa (fn 88,270b): At 4 a.m., about 40 chickens and two rams were killed, and their heads were cut off completely. Their blood flowed onto bows, arrows, and quivers (not seen). The arriving guests brought chickens as gifts for the deceased man. The fowl were immediately killed at the left side of the entrance to the compound. Their feathers were stuck to the wall; the de-feathered chickens were immediately roasted over the fire. Behind the house, sacrifices to the deceased woman were made.

5.2.3.2 Skin bag oracle

Ajuzong Yeri, Wiaga-Mutuensa (fn 88,270b): At around 8 a.m., a skin bag (bunlok) was opened. Millet grains and liquid shea oil had been poured into this bag the previous day. If the oil had hardened, it would be a bad sign – for example, a mistake was made at the funeral celebration, or one of the participants would soon die. In this case, however, the oil remained liquid.

5.2.3.3 Zong-zuk-cheka: Musicians on the flat roof (cf. 4.2.1.10 on Kumsa dai)

At the Juka funeral of Asiuk, Musicians played three ginggaung (cylinder drums), one namuning (horn trumpet), one sinleng (double bell), and one wiik (flute) on the flat roof.

U. Blanc (2000: 223): The drumming on the flat roof at dawn signals the beginning of the [Juka] ritual.

(p. 221): The kobisa of the deceased are responsible for the musical performance.

5.2.3.4 Preparation of the meal and its distribution (also for offerings to the quiver)

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Mutuensa (fn 88,272a): While it was still dark in the early morning, the widows prepared the millet porridge to be sacrificed to the quiver. At 9 a.m., neighbouring women had prepared the millet porridge with fish (jum-goalik) and yams and brought it in a procession to the house of mourning.

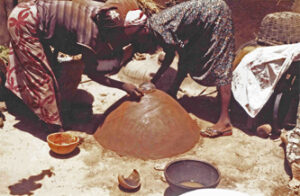

Later, about 20 kpalabsa-bowls with white or reddish millet porridge (from zamonta), and about 20 chengsa with sauce (see photo), and many calabashes with fish, yams, bumbota (edible tubers from the bush), koosa (bean cakes) and suma (round beans) were placed behind the granary (bui) in the cattle yard.

The food prepared for visitors from other sections was distributed. Only half and full orphans from a section were allowed to eat part of it. The names of the sections were called out one after the other, and each section representative could choose a dish. However, one black calabash was reserved for the sacrifices to the bow and quiver and for the elders. Some ‘impertinent’ guests took fish or meat from another dish in addition to their own. They might have been reprimanded but could not be prevented from taking this additional food. We were also offered food in the dabiak.

Miller porridge for visitors

Juka funeral of Asiuk (fn 94:14b): Over 20 bowls of millet porridge (mostly in chari bowls) and over 15 calabashes of chicken, guinea fowl, or fish were ready to be eaten. Some of the millet porridge was served with kamsa bean cakes. In general, yams must always be among the dishes served at such meals, but they may only be prepared by close relatives (daughters or widows of the deceased). All the prepared food was taken to the chief’s mother’s quarters and placed at the entrance to her room.

Speeches were held. Bowls of millet porridge were also placed in the quarters of Agoldem (Asiuk’s eldest living brother) and almost all the other courtyards. These bowls had been brought from other compounds. There was a red mass (of kamsa?) on one bowl.

Many people kept arriving with gifts (e.g., chickens, guinea fowl). They were obliged to give everything to Agoldem, Asiuk’s brother. A delegation from the Sandemnaab had also arrived.

Godfrey Achaw (fn 73,48b): The food is prepared in the room of the dead man and spread out in bowls in the courtyard: millet porridge, guinea fowl meat, chicken meat, meat from bush animals, dried meat, bean cakes, etc. Neighbouring women help with the preparation as needed. The chief mourner tells the women to [whom they should] give the food by pointing to them.

Yaw, 27 January 2006 (fn 06,6b): Millet porridge is also called lokta sira (‘quiver’s millet porridge’).

Aduedem (2019: 25): On this day, they cook Bambara beans, yams, cakes (kamsa), jollof rice, [and] bumbota (Tacca Leontopetaloides [endnote 102]), and an animal may be killed for the TZ. When the kobisa [return] on this day, each comes with TZ. By the evening, the TZ they prepared in the house is served in several earthenware bowls, including one very big one. TZ in a big earthenware bowl with a cake on top of the TZ is sent to the kusung dok for the elders, and another TZ and cake is given to the san-yigma of the widow for his toils. The yam is arranged around the TZ in a big chari [which will be given to the kobiik kpieng, the head of the kobisa], and the rice and some bumbota [are placed] on top of the TZ. Now, taking a chin sobli [endnote 103], they put a number of mudfish, the Bambara beans, and rice inside it. Then all the TZ is arranged in the courtyard (dabiak) with the TZ in the big chari together with [the] pots of pito. Then, the elders in the kusung are called in and told that these are the TZs, [and] they should use them to perform their funeral. The elders pick four bowls of the TZ with some pots of pito and give them out to be kept in the kitchen (gbalong/gbanlong). Then, they give one bowl of TZ to the [deceased’s] siblings (if any). After that, they ask everyone to snatch (chiak) the rest of the food.

Danlardy Leander, 17 April 1996 (fn 94,87b): Kamsa bean cakes are distributed (individually?) to relatives, neighbours, and friends.

Azognab (2020: 50; information provided by Akaalie Aginteby of Sandema in 2018): Every household among the kobisa (the family lineage) in the community) is expected to bring at least one kpalabk (a local ceramic bowl) of saab (millet porridge) with soup and either fish or guinea fowl meat in the evening of the sira manika dai to the funeral house. All this food, together with the one prepared in the funeral house, is presented and kept open in the courtyard where the funeral takes place. This is described as sira zaaka (‘the placing of millet porridge’). After a speech has been delivered by the kpagi (lineage head), the food is shared among the community members.

James Agalic, master’s thesis (fn 88,4a): Cooked food is brought to the deceased’s house by the kobisa. It is placed in the yard of the deceased. Nobody may enter this yard because the ancestors eat there from the food. After the lok cheka, the food is shared. The arrows are distributed among the sons of the deceased.

5.2.3.5 Parik kaabka, the sacrifice to the compound wall by men

Aduedem (2019: 25f): When the chiaka is over, the nisomba [elders] take their four bowls of TZ (kept in the gbanlong) and go to put them by the bui (barn) in the kraal (nankpieng) without uttering a word. Then they take the four bowls of TZ [back] outside and put them by the parik [compound wall]. Then, they call the kobisa to perform their sacrifice for them. Two of them get up and wash their hands with water. Then, fetching all the food items brought out plus bogta soup (prepared by the widow) into their left hands in the form of a mixture, they smear that on the parik while mentioning the name of the deceased, saying: ‘Fi ngandiinta ni nna, nuru bi mwan ka’ ([literally meaning] ‘this is your food; be aware there is no one [food?] again’). This ritual is done three times. Taking some pito, they pour it on the smeared food on the parik, saying: ‘This is your drink; there is no one [pito? person?] again’ … After that, they wash their hands. The rest of the food is eaten.

(p. 30): The sons also provide a fowl for the elders, and those responsible for sacrificing the wall use it to sacrifice to the wall again. As they smear the blood on the wall, they say: ‘That is all; there is no funeral in this house again [any longer]’, and children take it [the chicken] and roast [it].

5.2.3.6 Sacrifices to the bows and quiver

Note: Is this the kpagluk sacrifice described in 5.2.3.1?

Juka Funeral of Asiuk (fn 94:15a): At around 4 p.m., Asiuk’s quiver was brought from his mother’s room into the dabiak, and a chicken and then a sheep were killed over it. The dead sheep was thrown over the compound wall to the outside. The gravediggers (vayaasa) went out and skinned the sheep that was given to them, but everyone could eat it.

Juka at Ajuzong Yeri, Mutuensa: At around 4 p.m., about 40 chickens and two sheep were killed for the dead man’s bow, quiver, and arrows. The heads of the chickens were cut off completely. The dead sheep was thrown over the outer wall. The gravediggers went out and cut up the sheep. Its meat was for themselves, but everyone could eat it.

Aduedem (2019: 26): In the dabiak, the sons or other relatives provide a cock and a male animal (either a billy goat or a ram), and the log and tom (quiver and bow) of the deceased are brought. White untwisted fibre (bok pieluk) is used to tie the quiver and the bow together. The cock and the animal are sacrificed to the quiver. While sacrificing, mention is made, ‘Your sons are giving you these [animals].’ Only those whose fathers are late and their final funeral rites [have been] performed can eat the meat (that is sacrificed to the log). The cock is roasted outside, but only the liver and a piece of meat from the skinned ram’s forelimb (bogi) are roasted with the fowl. The presiding woman grinds salt and adds shea butter to it in a chin-sobili [black calabash]. The roasted meat is kept in the chin-sobili with salt and shea butter. [It] is used to sacrifice to the log again. (Anytime they are sacrificing to the log, they say ‘ngua fi nganta, nuri bi mwang ka’: ‘receive and be aware there is no person left’ [endnote 104]). After that, they use some pito and pour a libation on the log. They can then … chop their roasted meat while [it] is kept in the animal’s skin. When they have finished, they hang a [branch] of the damburing tree on the gbong, [which is] a ‘flat roof of [a] house, [a] raised platform (on top of a house’ [endnote 105]). The log is then carried by the two gravediggers (each holding one side of the log) and [hung] with the damburing on the gbong. Then, [they] leave for the kusung (outside).

5.2.3.7 Preparations for burning the quivers and other weapons

Juka funeral of Asiuk (fn 94,15a), 10 July 1994: On the fourth day two gravediggers carried the quiver like a mat from the dabiak to a flat-roofed house in the courtyard… The two gravediggers who later burned the quiver fetched it from the roof and brought it to the room of the chief’s mother, where they discussed the procedure for the following activities. Apart from them, only orphans were allowed to enter the room (e.g. not Danlardy, as his mother was still alive; I would have been allowed to enter).

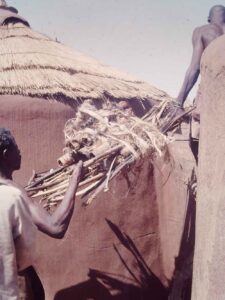

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Mutuensa (88,272a+b), 27 April 1989: A dambuuring branch with a light-coloured fibre was lying in the middle of the dabiak. The wood was used to burn the bow and quiver. Next to it, by the grave, there lay a bundle of loose mat stalks (see photo). In the dalong, men (gravediggers?) prepared a bundle with a quiver and bow. All the children were driven away. Someone fetched a very small, bloodlessly killed chicken and threw it over the nanggaang wall.

The white fibre and the dambuuring branch

Danlardy Leander, 18 March 1996: There are branches of the dambuuring tree (Gardenia erubescens?) on the quiver.

Godfrey Achaw (fn 73,49b): Bows and arrows are chopped into many small pieces at night. Children, old women, and people who cannot keep secrets may not be present (Godfrey was also always forbidden). The elder who chopped up the bow sacrificed a goat. All people with at least one parent still living may not eat the meat.

5.2.3.8 Sacrifice to the quiver in the dalong

Ngmiena stalks in Mutuensa

Aduedem (2019: 27): Those two gravediggers who performed the log ritual enter [the compound] again, and after removing the log from the gbong, they send it inside the dalong [ancestors’ room]. In there, they collect mwiena (ngmiena, straws of elephant grass), spread them [out] and put the log on them, and the mwiena are rolled around the log and tied with bog pielung [white fibre]. Another man comes into the dalong, sits [down] by the entrance and blows whistles while the daughter-in-law (if her father is dead and his final funeral rites were performed; otherwise, a different woman steps in for her at this time) uses mwiena again [and] lights [a] fire, and that fire brightens the room for the rituals in the dalong. The TZ, yam, rice, cake (kuosa, koosa), bumbota, etc., that are prepared (the second time) are used to sacrifice to the log [quiver] in the dalong. Let it be noted that no one whose father is alive or dead but whose final funeral rites are not yet performed is allowed to see the log kaabka (the sacrifice on the log). Again, as the food is cut and put on the log, the [phrase] ‘nuri mwan [ngman] ka nuri mwan ka’ [‘the man is no longer there…’] is repeated.

5.2.3.9 Carrying out the weapons

Carrying the bows and quivers out of Ajuzong Yeri

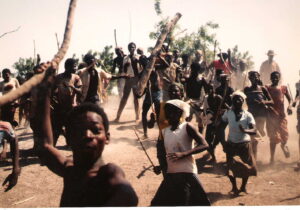

Juka funeral of Asiuk (fn 94.15b, under day 4): Gravediggers carried the weapons over their shoulders like a stretcher out of the (discussion) room and the compound. Men in everyday clothes danced a kind of war dance with sticks. As this was the last farewell to the dead man, the women wept.

Ajuzong Yeri, Mutuensa (fn 88,272b): After 9 a.m., two men carried out a bundle wrapped with a bright kazagsa fibre containing about ten quivers with arrows and ten bows. The bundle was wrapped with a light-coloured kazagsa fibre. Some weeping women followed the quiver (see photo). This was the final farewell to the dead.

Aduedem (2019: 27): When the sacrifice is finished, two people carry the log out while someone remains in the dalong watching the leftover food. As the two people move out with the log, the relatives of the deceased follow, mourning and wailing.

5.2.3.10 Chopping up and burning the weapons (lokta juka)

Chopping up a bow in Ajuzong YeriUpon the burning of the weapons, the soul of the deceased moves into a localised realm of the dead. For the Atuga-bisa, who constitute the largest group among the Bulsa, this realm is called

Ajiroa and is located near Chana. According to U. Blanc, the burned or broken things (weapons and pots) were returned to the dead via their destruction.

Juka funeral of Asiuk: The quiver that had been chopped up into small pieces (lok cheka) with an axe (liak) near the chief’s bui in the cattle yard was burnt. Greetings in the kusung followed the burning of the chopped-up quiver.

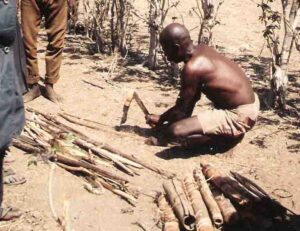

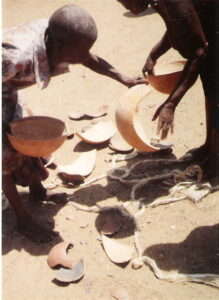

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Mutuensa (fn 88,272a+b): The gravediggers carried quivers and bows, some of which had traces of blood, behind the tampoi. There, they untied the kazagsa string and smashed the quivers with the back of an axe. They cut the bows in half with the axe blade on a wooden base (see photo). All parts of the chopped bows were burnt completely. As a reward for their work, the widows gave each gravedigger a calabash of fish.

Burning bows and quivers in front of Ajuzong Yeri

Ayomo Ayuali (fn 1994,50): His grandfather had two quivers. The quiver burnt at the Juka funeral was never used except for war dances and was made in advance for the funeral; Ayomo still used the second quiver for war dances. The bow of Ayomo’s FF was not in the compound, only that of his father (reasons?).

Danlardy Leander, 17 April 1996 (fn 94,87*): Anyenangdu also had two quivers; only one was burnt at the Juka.

Yaw (fn 97,38b): The quiver is turned around once before burning (tulim). This is why the day is also called lok tulimka dai. The burning always happens at the na-vuuk (cattle drift) in front of the compound. Before the destruction, a chicken and a guinea fowl are killed together over the quivers and ceramic pots. Two men hold the chicken, and a third cuts it in half (not at the neck!) with a knife. Many people are disgusted by this cruel (wicked) way of killing a chicken. They run away or look away; those who watch may become blind. The name of the ritual is bantika (‘to say goodbye’). Cf. kpiak gebika: 3.4.1.2 and 3.7.2.1 (ngarika).

Aduedem (2019: 27f): When they get to the kraal, they put the log by the bui and cut it (the log) [and] the dambuuring into pieces, and the woman who set the fire in the dalong brings that fire, [which] is used to set the pieces of the log on fire [endnote 106]. It is only at this point of burning the quiver (log) and bow (tom) – or, in the case of a woman, the destruction of the puuk – that the soul of the dead is released and can now properly enter the land of the dead [endnote 107]. These rituals of destruction evoke strong emotional outbursts [from] close relatives because only then have they finally lost their relatives [endnote 108].

When the fire is dying down, the two gravediggers tell the sons of the deceased to put out the fire [that is] burning their father’s quiver. The sons bring a pot of pito and a hoe blade, [which] are put aside. The daughter-in-law (or the woman who stepped in for her, depending on whether her father is alive) who set the fire in the dalong also brings another pot of pito and water. The two gravediggers pour her pito and the water into a calabash. [Using their left hands, all those in the kraal] fetch the contents (pito and water) in the calabash and wash their faces (to wipe away the tears from the crying) while moving around the burning quiver. The rest of that pito is poured on the fire, and the hoe blade is thrown into it (the fire – or perhaps ashes by then), saying they are quenching the fire [that is] burning their father’s quiver.

J. Agalic, master’s thesis (fn 88,4a): The eldest son performs the lok cheka. After that, the food is shared. The arrows are distributed among the sons of the deceased.

U. Blanc (2000: 222): At the Juka for a man, the quiver, bow, and arrows are broken and burnt.

5.2.3.11 Destruction of pots in front of the compound

Destruction of pots in front of Ajuzong Yeri

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Mutuensa (fn 88,272b): Women brought a bimbili pot and one (or two?) calabash(es) out of the compound to the place where the gravediggers had destroyed the quivers. All the vessels were smashed to the ground. This ritual was performed on the men’s side of the compound for women who, as ‘daughters of the house’ (yeri lieba), did not die in a foreign compound (see photo).

5.2.3.12 War dance in everyday clothes and ‘first storming’ of the tampoi

Juka funeral of Asiuk (according to information from Danlardy Leander): While the quivers were being carried out of the compound, young men in everyday clothes danced a war dance with simple sticks. After carrying the quivers out, they all stormed the rubbish heap (tampoi) three [?] times.

Ajuzong Yeri, Mutuensa (fn 88,272b): Even before burning the weapons was completed, a boy of about 15 years ran around the compound with a zangi forked post. He was followed by boys and girls shouting wildly. They carried sticks, zanga (forked posts), and dalta (rafters). Then, one boy hurried up the high tampoi, and all the others followed him. In this way, the tampoi was “stormed” several times. Girls also formed themselves into war dance groups and paraded around the house several times. The groups displayed ritualised, aggressive attitudes towards guests (including F.K.) by running towards them threateningly and then leaving them again.

‘Storming’ the tampoi in Wiaga-Mutuensa

Aduedem (2019: 28): As the fire is burning, the sons of the deceased continue wailing and performing a war dance (lielik) since [while?] the fire is burning their father’s quiver. This fire burning is also viewed [as] a natural fire disaster, [which] is why they perform the war dance: [it is] a sign of their readiness to rescue their father’s quiver.

Atuick (2020: 91): …(Atuick: Fourth day). All who consider themselves children of the deceased man, including the cheri-deiroa, perform a war dancing over the remains of the louk.

5.2.3.13 Burning of the mat stalks

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Mutuensa (fn 88,272a+b): In the house, a small fire was still burning in the dalong. The stalks of the mat that had been lying loose in the courtyard next to the dead man’s grave all morning were burnt there (see also 5.2.3.8).

5.2.3.14 Puuta mobika or puuta cheka (destroying the puuk pots)

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Mutuensa, (fn 88,273a): At around 11 a.m., on the main road leading to Yisobsa, Chiok and Badomsa, the destruction rituals for the pots of the women who died as wives in the mourning house took place.

Destruction of the calabashes and clay pots of the deceased wives (Mutuensa)

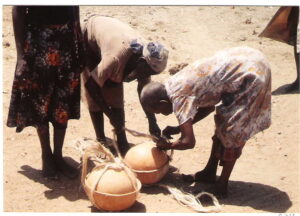

11 a.m.: Three women (from Yisobsa, Chiok and Badomsa) brought two double calabashes (base calabash bowl and lid) that were tied with white kazagsa fibres to the path for the deceased woman from Yisobsa. Before opening the lacing, the woman from Yisobsa knocked four times on the upper calabash. Inside the calabash was a kpaam-kabook (clay pot for shea butter, here with a square lid, see photos). Some informants call the vessel puuk, whereas puuk usually means a knobbed pot. The women broke the lower calabashes (partly with their feet) on the path and brought the intact lids back into the compound.

11.35 a.m.: The same women destroyed the vessels for the deceased woman from Atana Yeri (Chiok), a little behind the first destruction site. The kpaam-kabook contained foods like dried chicken meat or dried fish. The empty clay pot was thrown to the ground with a swing from a height of about half a metre, and broke it. The intact, smaller calabash with the food from the kabook was carried back into the house.

Various forms of kpaam-kabook (puuk)

12 p.m. (fn 88,273b): The same ritual was performed for the woman from Badomsa. Here, too, a woman tapped the calabash four times before she opened it. The clay pot held no contents. This time, a woman knocked it on the ground. The same happened with the larger calabash, from which only one piece broke out. The pot rituals (puuta mobika) were completed at 12.20 p.m.

Ayoling Yeri, Wiaga-Badomsa (fn 88,197b); the Juka was only observed from Asik Yeri on 28 January 1989: Anurka’s younger brother Abarimi died exactly five days after Leander. A woman carried out the puuta mobika. There were several large pots between the two kusungta.

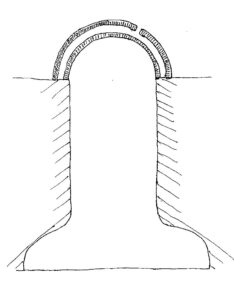

Awaribe Yeri (the rain god’s house, Kobdem, my observation and information from Baba in Sandema-Kobdem, fn 1984,27a+b): At the back of the compound, ten clay pots were stacked in two sets of five each. From bottom to top, the vessels were stacked as follows: samoaning, bimbili, kpalabik, kaam-soluk, and cheng. The upper two pots had fallen from the left pile, but no one was allowed to touch the pots (to replace them) except gravediggers (vayaasa) or a widower whose wife’s funeral had already been held. The pots belonged to Atinpilie (my watchman’s wife), whose funeral was brought from the neighbouring house. The second wife was Apoaliba, the mother of the yeri nyono. Only she had lived in the dok (room) located by the outer wall where the pots stood. The pots were only part of the women’s household goods; the other pots were still used in the house. In the puuk ritual of the Juka funeral, the pots will be held by four women and taken to the path leading to each woman’s parental home (in this case, Kandem and Wiaga). They will release (one?) pot at a time. If it does not break on the way, it is a bad sign – for example, something has been done wrong, or the dead woman is angry because something has been forgotten. The shards will be pushed aside; they no longer have any meaning. Calabashes will also be destroyed with hands or feet along the way.

Atoaling Anueka and my observation (fn 84,0b, also 84,23a): In Anueka-Yeri (Sandema-Yongsa), I observed three stacked samoaning pots in the cattle yard by the outer wall belonging to Abiako’s wife (Anueka’s mother). They were supposed to be outside the compound by the outer wall, but the wall had collapsed. The pots would be destroyed during the woman’s Juka funeral. In contrast to Kobdem, there was no ban on touching them here.

Margaret Arnheim (Gbedema) 1978ff (fn M5b+34a): Several pots are broken on the footpath to the deceased woman’s parental compound. They are not typical cooking pots.

Agoabe (Anamogsi’s son) on the Juka (of an unknown individual) in Anyenangdu Yeri: Destructions took place on the seventh day (with this counting probably including the rest days). Esi and Achiilie (married to Anamogsi’s sons) broke the calabashes and pots that the dead women had used during their lifetime. Some of the vessels had been given to them by daughters-in-law. The calabashes and clay pots are called senlengsa (‘double bells’).

Yaw (fn 97,38b): According to Yaw, a knobbed pot (puuk) is destroyed.

Danlardy Leander (fn 97,61b*): Only the pots of older married women are destroyed, not those of young women.

Sandford from Kadema-Kpikpoluk (fn 73,161b): At the funeral of a woman who has borne children, a knobbed pot is broken at the intersection of important footpaths. The shards remain there. A new knobbed pot is provided with leaves and roots; it later receives sacrifices.

U. Blanc (2000: 222): Women from the dead woman’s section of origin break their pots on the way to their parents’ compound.

Atuick (2020: 91): However, the Juka rites of a woman are much more complex, with the cheri-deiroa playing an influential role. In this case, women from the paternal home of the deceased mother-in-law must arrive [during] the evening of the third day of the [Juka] rites. They usually come along with their own puuk [a ball-like ceramic vessel with a lid that symbolises a woman’s womb during funeral performances] to participate in the rites. [As a group,] the wives in the compound … must acquire a puuk for the rites to commence. The cheri-deiroa must also acquire a puuk for the rites. The next morning, on the fourth and final day of the rites, the visiting women will take their puuk to the san-yigma’s compound to hand it over to him and ask him to help them present it to the husbands of their sister(s). The san-yigma then leads them to the compound where the deceased lived, exchanges pleasantries with the elders, and hands over the puuk to them after making the following statement: ‘As our daughter is preparing to go home, this is something that belongs to her that we have brought for her to take along with her.’ The family collects it, after which some women from the compound sponsoring the funeral go to the compound of the san-yigma with their own puuk, flour, and meat from both the animal killed and a guinea fowl [to use in] the saab for the performance of the rites. They prepare the saab there and place it in clay bowls before carrying the food and the puuk towards the funeral house. Before they get to the funeral house, they wait at a distance from the compound.

(p. 92) The following day, all three puusa [plural of puuk] are taken back to the same spot where the women met the previous day and broken into pieces, except for the puuk provided by women of the deceased person’s compound, which is handed over to the cheri-deiroa for keeping. Thus, the puuk provided by the women from the deceased’s paternal home and the one provided by the cheri-deiroa are both destroyed, but the one from the wives from the compound sponsoring the funeral is presented by the chilie to the cheri-deiroa as an inheritance from her deceased mother-in-law. [As] the eldest son’s wife, the cheri-deiroa receives this puuk as the rightful inheritor of the deceased’s household and property, and she is expected to keep it until her own demise.

5.2.3.15 Dancing on the potsherds

Margaret Arnheim (Gbedema): Only people from her own section will dance on the potsherds. The impersonator of the Juka funeral is also present at the potsherd dance. Margaret was potentially able to dance at this ritual in the Gbedema Chief’s compound.

5.2.3.16 Production of a fine, light-coloured powder

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Mutuensa (fn 88,273a), 11.30 a.m.: Somewhat off the path, a woman ground a soft, light-coloured stone into a fine powder on a shea butter grinding stone (the meaning of this powder was unknown).

5.2.3.17 The grave

Women plaster the grave of the deceased

During the Juka celebration, the grave cover of the deceased is given a final plastering by women – usually on the third day, but according to Aduedem, the plastering happens on the first day. Today, the grave plaster usually includes an admixture of cement. Millet grains are scattered on or around the grave, and, for example, a chicken and a mammal are killed (this activity has sometimes already occurred during the Kumsa celebration, such as at Awuliimba’s Kumsa). The animals are intended for the deceased’s use, but they are not real sacrifices.

A summary of all rituals and other activities at the grave after the burial can be found in Part 5.3.

5.2.3.18 Imitation of the deceased by a woman

Juka funeral of Asiuk (fn 94,14a), my direct observation, 4 p.m.: A woman (Akantoganya’s wife, the daughter-in-law of the deceased chief), wearing a saba-garuk (a magic smock with many amulets and charms) underneath a long white robe, imitated the deceased Chief Asiuk (see photo). She wore Asiuk’s sunglasses and carried his stick. While wearing the saba-garuk, she was not allowed to speak a word. As Asiuk was known to drink heavily at feasts and sometimes refuse to enter a compound, this imitator played a slightly drunk, stubborn person to portray Asiuk. A woman dressed in a blue smock with a blue cap always accompanied her. She was imitating the ngaang-viroa who had always accompanied the chief (he had also died, but his funeral had not yet been held). Awaab, a man in European men’s clothes, also accompanied the two women. He had been the chief’s messenger.

(fn 94,14b) 6 p.m.: The impersonator took off her inner magical smock and was then allowed to speak again.

5.2.3.19 Visit to the market

Juka funeral of Asiuk (fn 94,14a): Between 5 and 6 p.m., a group of funeral participants moved to the market. In front were two hourglass drums, two calabash drums, and three flutes; behind the procession were four cylindrical drums and six namuning horns. Joining the procession were two female impersonators as well as the incumbent Wiaga Chief of Accra; Ayabalie, the youngest daughter of the deceased; Afulanpok, his youngest wife; and numerous children (see photo).

Procession to the market, with Asiuk’s impersonator at the centre

Market stalls were covered with blue tarpaulins

At the market, all children were allowed to plunder the market stalls with edible goods without fear of punishment. Some vendors had covered all the goods with blue plastic tarpaulins (see photo); one merchandise vendor presented her goods uncovered, but she showed me a thick stick as a deterrent for the children [endnote 109]. People danced under the nim tree to the sound of cylinder drums and horn trumpets. On the way back to the compound, different horn players played, as they had been replaced after the first players had become tired. A new piece of music began first with beats played on the hourglass drum, and then the calabash drum joined in, with other instruments joining until all were playing together.

5.2.3.20 Compensation for services and gifts

Aduedem (2019: 28): The sons brought the pito earlier together with any amount of money. [Giving money] is not compulsory; it is only a way of showing their social status, generosity, and appreciation. They give everything to the gravediggers. The rest [of the people] walk out, and the two men [gravediggers?] go inside the dalong to eat the food they left there. Some of the food is given to the one who blew the whistle – some to the women who set the fire – and some TZ is put into the ‘black’ calabash (chin sobli) and given to the [presiding?] woman to [give] to the orphans (the biological children of the deceased) the following morning. That TZ is called kpingsa saab (orphans’ TZ).

5.2.4 The fourth day: Senlengsa dai (the double bell day) or daata nyuka dai (the day of drinking pito), according to Azognab, also kusung puusika dai (day of greeting the elders)

(F.K.) I could not observe the events of this day myself.

U. Blanc: The last day of Juka is the day of crowds, dances, and music, but [it has few] rituals.

5.2.4.1 Millet porridge (saab) for the orphans

Aduedem (2019: 29): In the morning of this day, the [presiding] woman [chelie] takes the TZ (in the chin sobli) she kept aside the previous night and sits [down] at the entrance of the dalong. Calling each of the decased’s biological children (from the oldest to the youngest), she cuts small [pieces] of the TZ, scolds [endnote 110] him/her [the orphans] and gives it to him/her to eat. She does [this] three times each for all the children. The scolding takes this form: ‘Nwua [ngoa], fi a kping ka nna, fi puom bagaa nya ka nna yeg-yega. Ka wana tim pa wa nganta a te fi a kping ka nna?’ That is, she says, ‘Take this; you [are] the orphans; you are even looking too much. Who will give food to orphans like you?’

5.2.4.2 Completion of the millet beer preparation and its distribution

Aduedem (2019: 29): Afterwards, the elders in the kusung dok sent two men inside to the presiding woman to [learn] whether there was pito from the pito malt (kpaama) they gave her on the first day of the Juka rites). The woman then calls the first son of the deceased and shows him the pito in the pots. She takes a pot of pito, and the son takes calabashes (daam china: pito calabashes), and they send them out to the elders [while] saying, ‘This is the dirt of the deceased.’ Out of courtesy, the elders would ask that some of the pito be given to the mothers-in-law (nga niima) of the deceased who have come to witness the funeral rites. However, the sons would opt to provide a different pito for them (the mothers-in-law). More pito may even be supplied, which everyone drinks – hence the name ‘daata nyuka dai’ (literally [translated as] ‘pito drinking day’) for this day: This is the day on which the pito (daam, meaning alcoholic drink) is drunk.

Azognab (2020: 51; information from Akaalie Aginteba of Sandema in 2018): Damonung (‘pito’), [the] preparation [of which] was begun on day one of the Juka ritual, is provided for the elders. If the deceased person in question is female or unmarried, the funeral ends with the greetings of the elders and the ‘pito’ party among them. If the deceased person was a married man with a surviving wife or wives, this last day will also mark the day [on which] the widows or widow chooses a new husband.

5.2.4.3 (Second) Market visit

Juka funeral of Asiuk (information via Danlardy), 12 July 1994: At the time of the climax of the celebration, the daughters of the deceased chief wanted to go to the market to indicate that the funeral had been held successfully. Before that, however, aggressive bee swarms swept the whole market empty. This event was interpreted as Asiuk wanting the market to himself. The sale was then moved to the crossroads (Goansa). Dances were performed in front of Danlardy’s house as he is a relative of Asiuk. He donated one bottle of Akpeteshi and one calabash of millet water.

5.2.4.4 The ‘offering’ to the compound wall

Compare 4.2.4.6: Parika kaabka at the Kumsa)

Aduedem (2019: 30): The sons provide a fowl for the elders. And those … responsible for sacrificing the wall [at the Kumsa, on the gbanta dai] [use] it to sacrifice the wall again. When they smear the blood on the wall, they say: ‘That is all; there is no funeral in this house again [any longer].’ [Then,] children may take the fowl and roast it.

Atuick (2020: 91): Following the war dancing, the eldest son of the deceased performs the final sacrifice of the rites on the left wall of the main entrance [to] the compound. While standing there, he gathers all the live fowl brought from the earlier visit to his late father’s [maternal] lineage [or] donated by friends and sympathisers to help him complete his father’s funeral rites; [he] sacrifices them on the wall. He does this by hitting the fowls, one by one, against the wall to die. While their blood flows down the wall, he says, ‘Ba ko parik! Ti kowa kumu yai nueri kama!’ [‘They have killed a wall! Our father’s funeral is now over!’]. This sacrifice [demarcates] the end of the funeral rites for the deceased man and, by extension, the role of the cheri-deiroa. The next thing is for all the dead birds to be plucked and cooked for all present, including the cheri-deiroa, to eat to their satisfaction before dispersing.

Danlardy Leander (fn 1994,60b): On the last day of the Juka, kamsa cakes are smeared on the wall of the house (no further confirmation of this information was available).

5.2.4.5 Remarks on the senlengsa dance

Adama (Chiok) via Danlardy (fn 88,305b): The senlengsa dance was cancelled at Asiuk’s funeral, as this dance is only performed for females. The ritual probably exists throughout Bulsaland. Danlardy has evidence for it in Chiok, Guuta, Yimonsa, Longsa, Wabilinsa, Kori, Kom, Siniensi, Fumbisi, Sandema, Wiesi, Kanjaga, Doninga, and Chuchuliga.

Adama dancing the senlengsa dance

At a Juka celebration in Chiok, Adama’s sister gave her brother a shard from the destroyed calabashes of the dead. Adama placed it on his head and danced. This dance expresses the joy that ‘the dead have been driven away’. The musical instruments played for this dance are the ginggana (cylinder drums), namunsa (horn trumpets), gori (calabash drum), gunggong (hourglass drum) and wiisa (flutes). In Chiok, they did not have an iron senlengsa (double bells) at hand, so they took a glass bottle and hit it with a stick.

Yaw (fn 97, 38b): When a matrilineal relative participates, he takes a potsherd or a splinter from the quiver, places it on his head, and dances with it. He then throws it away.

U. Blanc (2000: 229–32, here: abridged excerpts, pp. 229–30): The double bell dance (senlengsa gokta) [in row-formation] … is [only] danced … by women [for deceased women]. The only accompaniment is the double bell and hand clapping. The singing is purely choral (without a female lead singer). A daughter of the deceased usually leads the dance. Boys and men can also join in when their sisters dance. They dance on the shards of the destroyed pots and balance the shards … on their heads as they dance towards the deceased’s parents’ house.

The dance is a mark of honour for older wives who have lived in the compound for a long time and given birth to many children. [The] senlengsa yiila belong to the kum-yiila (songs of the dead).

5.2.4.6 Naapierik ginggana (dance to the ash heap)

U. Blanc (2000: 221): The kobisa of the dead are responsible for this dance.

(p. 223): The dance … of the men to the ash heap ends this final phase of the Juka.

(p. 227): It corresponds to the [senlengsa] dance for a dead woman and is a kind of farewell greeting.

(p. 228): Ideally, [no other instruments but] 3–4 ginggana [are played]… Only experienced men (good singers) may join in the [unaccompanied] singing. The eldest son of the deceased (or possibly a substitute) should lead this line dance [with] slow, deliberate steps.

5.2.4.7 Procession to the guuk of the compound

Danlardy Leander (5 September 1996): On the senlengsa dai of important men’s funeral celebrations, the funeral procession marches to the guuk of the compound.

5.2.4.8 Remarriage of widows (not observed)

According to several informants from Sandema (such as Godfrey Achaw, Aduedem, and Azognab), remarriage only occurs on the fourth day, but in Wiaga, it may sometimes take place on the third day. See also Kröger 1978: 291–94.

Juka funeral of Asiuk (fn 94,15b, information via Danlardy): All the widows gathered in the chief’s mother’s room, and they were asked one by one whom they wished to marry. Five of them married the chief’s grave (‘ba yali naawa boosuku’), meaning they continued to live as the late chief’s wives. Later, they would still be able to marry another man. Then their children would belong to the new husband.

Anoalisikame, the youngest widow, married the deceased Albert Agoldem, whose funeral had not yet been held; Akanngarayuk, the second youngest widow, married Owen Agoldem; and Asebalanye, Clement’s mother and the third youngest widow, married Peter Anang, a former Catholic priest. The widows had to wear leaves until their marriages were announced, after which they could wear ordinary clothes.

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Mutuensa (88,273b), evening: The widows wore leaf aprons. They were not allowed to speak to or be touched by any man – either act was considered consent to marriage. However, when I unknowingly thanked a widow for her lunch with a handshake, the touch caused no fuss, just some laughter.

Danlardy Leander (?): When a widow is asked to choose for the first time, she replies, ‘Nyiam diem tuila kama!’ (‘The water is not yet hot’, meaning that she wants to wait a little longer). Then, she chooses a man who gives her a guinea fowl or money. Two (classificatory) sisters (from the same compound) can (must?) marry the same man, but two consecutive sisters (of the same mother?) in birth order may not.

Godfrey Achaw (fn 73,19b): Sons may marry the wives of their deceased father, as long as the chosen wife is not their biological mother or comes from the same section as their biological mother.

(fn 73,33a): A remarriage [F.K.: or consummation of marriage?] may not take place until the day after the termination of the funeral celebration. A woman should choose her new husband from among the men of her deceased husband’s compound or from the four related compounds [F.K.: kobisa]. If she wants to marry into her husband’s section, she leaves the house secretly at night and goes immediately to her new husband’s house (not to her parents’ house). This new house is not considered an enemy of the old house, and the new husband pays nothing to the old house or the woman’s parents’ house but only informs the latter and the first husband’s relatives.

No remarriage rituals exist. If the first spouse has not yet closed the ‘gate’ (nansiung lika), the second spouse must do so (see Kröger 1978: 374–76). If the widow does not want to marry into the section of her deceased husband without having already made a new choice of spouse, she first goes to her parents’ house, and her suitor would come to this house. All the rituals and payments take place as for a first marriage. The woman’s new husband becomes an enemy of her first husband’s relatives, who are not informed about the new marriage.

Leander Amoak (fn 79,2b + 8a): After the death of a woman’s husband, the children of the husband’s other wives have the first claim on their father’s wives [to marriage], since the new offspring will sacrifice to the wen of the deceased (their grandfather). If a brother of a deceased man marries his widow, the children will later sacrifice to the new husband’s (brother’s) wen. For example, Leander is the person who is most entitled to marry the widow of his deceased brother, Atiim, because he [Atiim] had no children by other women.

Agoabe (Anamogsi’s son; information from an email dated 12 March 2009, fn 08,B19): The choices of remarriage made by the widows of Akanpaabadai, Anamogsi’s son, were linked to the bathing of the widows at the tampoi. A gaasika (see above) was performed before the bath. The rituals were led by the women from neighbouring sections, by Afulang from Atuiri Yeri and Akansagba from Adum Yeri (Badomsa). During the election, the men were sitting in the kusung, and each widow said the name of the man with whom she wanted to bathe. Also invited to the Juka were the deceased’s wives who no longer lived with him before his death or had married another man. Without such an invitation, these women’s children would no longer be regarded as children of the deceased.

Agoabe (information from an email dated 24 March 2009, fn 08,B19b): A woman who has already been married twice in a compound may not marry someone from this compound a third time. She may, however, continue to live in the compound or marry a man from another lineage. No one from her deceased husband’s compound is officially responsible for her. Later, her children will likely care for her.

Notably, Yaw provided similar information.

Yaw (2002; with information similar to that from Danlardy in 2004): A young widow might have already bonded with a new partner sometime after the death of her husband and before she can officially choose a husband ‘since she cannot be expected to wait several years until the Juka’. At the Juka, she will then name this partner as her chosen husband.

(fn 02,21b): Abiisi’s Kumsa-funeral could be held (2002) before or after Anyenangdu’s Juka. As soon as Abiisi’s infant is weaned, his young wife could remarry, as she cannot be expected to wait until Abiisi’s Juka. She would then be expected to choose a brother of her deceased husband as her new husband. If she wants to marry a man from another section, she will leave Anyenangdu Yeri.

Yaw (2008): When choosing a husband, widows can also say that they want to marry a particular young boy. Such a union is not and will not be a proper marriage – indeed, they do not even live together. One compound head was very annoyed that many younger wives who were still able to bear children had ‘married’ a child. In addition, when a widow gives birth to a child by another man after the death of her husband but before the ritual remarriage, this birth is called zukuusa. If a zukuusa woman visits a sick person, especially between Kumsa and Juka, the sick person will be healed.

Yaw (2011; fn 1b): After Anamogsi’s death, his sons endeavoured to take care of their younger stepmothers. The Christian widows refused to become the wives of a married man.

Danlardy Leander (fn 02/04, 54*): Any of Abiisi’s brothers could not officially marry his widow before Abiisi’s Juka, but a brother could still live with her and even have children with her. At the Juka funeral, the brother who wanted to marry her would officially claim her as his wife.

Aduedem (2019: 29): …the elders send two men again to the presiding woman, telling her to ask the widow [whom she wants to marry] since the funeral rites of her late husband are over. The two men will do this four times. She can marry anyone from the extended family, and in the case of a polygamous marriage, she can even marry any [son] of her co-wife (but never her own son), or she can decide to remain unmarried by marrying the grave of [her] late husband [endnote 111]. After the fourth round, the presiding woman comes to the elders and announces to [them] the name of the person she (the widow) wants to marry. This remarriage is a ‘ritual proper for the reintegration’ of the widow into society, and after [it], the widow starts wearing her normal clothes again [endnote 112].

The person she mentioned [will then be] called by the elders, and he is asked to provide a basket of millet, a guinea fowl, pito, and tobacco. When he has provided them, the elders call the presiding woman and give the items to her. Those items are for the presiding woman because the understanding is that the widow is her daughter, and she has just handed her daughter’s hand in marriage to the said husband.

Azognab (2020: 51–53; information from Akaalie Aginteba, Akanvarilami Ataasapo, Atgenglie Awurung, and Adoruk Achumwari, all from Sandema, in 2018):

The Bulsa concept is that the widow or widower who shared [his/her life] with the deceased person in a very intimate way during their lifetime may want to take the spouse along for the companionship that they shared on earth, and hence, it is only the widowhood rites that separate them. Connected to this is also the belief that their union in marriage is not broken by death but by the funeral celebration of the deceased person…

At this stage, the Bulsa believe the widow can remarry on the final day of the Juka ritual, [which was] described earlier. The widow is usually [pressured] to choose her new husband from her husband’s family. Again, the Bulsa believe the widowhood rites are necessary to purify the surviving spouse of the daung or daunta (mystical dirt) of the deceased person. This [purification] is necessary for reintegration.

(p. 52–53): The widowhood ritual begins on day one when a spouse dies. As soon as he dies and the corpse is bathed and laid in the dalong, the widow is separated and sent to another room where other elderly women, as consolers and supporters, stay with her to guide her and provide for her needs. She remains in that room until the burial takes place. This separation continues until the final funeral rites are performed and the widow is re-integrated. If the final funeral rites are [not held] for [a long enough time], the widow may be free after some period of time to go about her usual duties, but she is forbidden to marry until the final funeral rituals are completed. A widower, on the other hand, sits outside and is surrounded by his friends from the community who make sure [to] give him the support that he needs.

Throughout the dry funeral celebration of her husband, the widow wears only vaata (leaves) and sits on shea nut leaves in a confined room. A widower, on the other hand, sits on the skin of a cow.

5.2.4.9 Discarding the body cords (miisa folika) and the second head shave

Juka funeral at Ajuzong Yeri, Mutuensa (fn 88,270b): Many women wore two or three twisted cords like sashes over their shoulders. These women were close relatives of the deceased who were smeared with daluk at the Kumsa. Many among them wore these twisted cords as waist cords (which are invisible from the outside). At the end of the Juka celebration, the cords would be chopped into small pieces with a stone on a footpath.

Danlardy Leander (fn 1994,80*): The jom-suiroa (su: ‘to put on’) removes and cuts the widow’s cords without any accompanying rites and taboos. After this ritual called miisa folika, widows are free to marry (the chosen husband?). The jom-suiroa, who is always a woman, is chosen immediately after the death of a man (husband) and then must fulfil several tasks. Immediately after the man’s death, she puts the cords on the widows (verbal noun describing this action: jom-suka) and bathes them (see above fn 1994,82). At present, the cords are not always worn before the miisa folika ritual but are kept – for example, by Danlardy’s mothers in their bedrooms under ceiling rafters.

Asiuk’s wife with widow’s strings

Asiuk’s widow, Clement’s mother (fn 94,74b): Like all widows, this woman wears a cord (miik) of twisted kazagsa fibres around her neck, around her left hand, and around her left foot. All cords end in a double (split-up?) cord with 3–4 knots.

The neck string must have at least one knot; the other knots are used to adjust the string to the widow’s neck.

Aduedem (2019: 30f): One week later [after the Juka Funeral], the widow cooks Bambara beans (suma) and makes cakes (kamsa), and the man who shaved her (on the nyaata soka dai) is invited. He comes and shaves her again, and after that, he removes the ropes she wore as beads [in a necklace?] during the [whole performance of the funeral rites]. No one is supposed to see those ropes, so he buries them in the tampoi (the rubbish heap). The widow then serves the man some of the Bambara beans and the cakes (kamsa). After eating, the man thanks the widow and tells her that the man she chose is duly her husband thereafter, and he goes to his house. [This signifies that] everything has come to an end.

(p. 32): [The widow is shaved] on the jueta soka dai and [again] a week after on the kusung puusika dai. All these [rites] are to cleanse her of the old life as a wife to the deceased. Thus, when the final funeral rites have been performed, the surviving spouse no longer belongs to the deceased; she or he starts a new beginning altogether, and [thus], in the case of a widow, she can marry again.

5.2.4.10 Koaling tika (the giving of goods; inheritance)

At the end of the Juka, the material legacies of a deceased man are collected and distributed among his heirs.

Yaw and Aleeti (fn 01,2b): The next-eldest brother of the deceased inherits all important and valuable possessions immediately after his death, as this brother needs the funds to finance the funeral celebration. However, if he refuses to organise the celebration, he inherits nothing. Personal belongings of the deceased (e.g. books) go to the children of the deceased; personal belongings of a deceased woman, such as a sewing machine, go to one of her daughters. As an example, Anamogsi’s eldest son, Asuebisa, would inherit nothing because [as a Christian?] he does not want to perform the funeral celebration.

See also Kröger (1982: 64–77, ‘Ancestor Worship…’).

Asage from Adum Yeri, Badomsa (fn 81,16b): This information details a case of prevented inheritance and succession. When Ajogyam, a grandson of Abadomgbana, was the earth priest (teng nyono) of Badomsa, he wanted to hold funeral ceremonies for two ancestors. Through these ceremonies, he would probably also have become an elder (kpagi) of the whole of Badomsa, so a group of elders prevented these funerals to prevent a concentration of power in one individual. Even today, Abadomgbana’s descendants can never acquire the wen of Abadoming, the section founder (without holding the aforementioned funerals), and the office of earth priest rotates only among the descendants of Abadomgbana.

Godfrey Achaw (fn 73,19b): The land that lies in front of the compound and which the deceased head of a compound inherited from his father goes to his brother, as does the entire compound, while all other land goes to his eldest son [F.K.: This statement seems imprecise and unlikely]. The livestock that he inherited goes to the eldest brother. Any livestock acquired during his lifetime goes to his eldest son. If the eldest son sells any of the inherited property, he must share the proceeds with his brothers.

Aduedem (2019: 30): If the deceased was a landlord (yeri nyono), the elders [would] call all those concerned (from the house) to the kusung dok and tell the sons that their father is no longer there [and who their landlord would now be].

5.3 Excursus (summary): The grave and its covering vessel (boosuk)