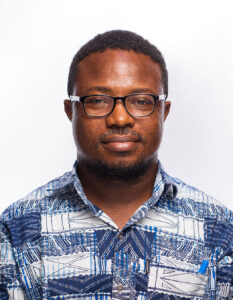

Kwesi Amoak

A GERMAN ANTHROPOLOGIST AMONG THE BULSA:

FRANZ KRÖGER IN CONVERSATION WITH KWESI AMOAK

Kwesi Amoak

Franz Kröger

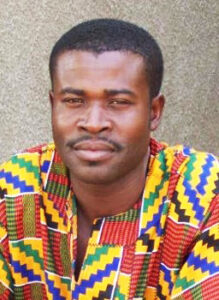

Kwesi A. Amoak, Mellon PhD Candidate, Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana

Franz Kröger, PhD, Institute of Ethnology, University of Münster

Abstract

In this three-part biographical conversation, Kwesi Amoak engages with Franz Kröger, a German anthropologist who has devoted over five decades – since 1972- of his intellectual life to ethnographic research among and with the Bulsa of northern Ghana. Through his reflections, we discover more about his formative years, what led to his lifelong interest in Bulsa culture and insights about his work, which includes several publications, notably the Buli-English Dictionary (1992) which has subsequently been developed into a mobile app for Android smartphones or tablets, and Ancestor Worship among the Bulsa of Northern Ghana (1982). His other works include a collection of over 500 material objects on Bulsa culture temporally hosted at the Völkerkunde Museum Werl, and, Buluk, a journal of Bulsa culture and society. By learning from his unique perspectives and experiences of challenges and limitations, we are able to speculate on prospects for further/future research and collaborations.

Keywords: Anthropology, Atuga, Bulsa, Buli-English Dictionary, Northern Ghana, Rüdiger Schott.

Part I: Formative Years

Germany in 1937, Kröger’s birth year

Kwesi Amoak (KA): Franz, thank you for agreeing to have this conversation with me. To start with, what circumstances surrounded your birth on 11 March 1937 and how was it like for you growing up in Braunsberg (East Prussia)?

Ferdinand Kröger

Franz Kröger (FK): Even some of my intimate friends are surprised when they learn that I, who have always been regarded as a typical Westphalian, was born to Ferdinand Kröger and Antonia Kröger, née Spiegel in Braunsberg (East Prussia), which now belongs to Poland now. The reason can

Antonia Kröger

be found in my father’s career. Born into a worker’s family (his father was a locomotive heater), he learnt the trade of a locksmith. On his own initiative, he attended the Baugewerkschule (a kind of technical college) in Höxter to become a building engineer (Bauingenieur), at that time a fairly significant profession. But when the time for earning money came, he suffered from the general unemployment period in Germany and could not find an occupation in or near his birthplace Paderborn (Westphalia). Then he was offered an occupation for bridge constructions of motorways in East Prussia, which was separated from the rest of Germany by Polish land.

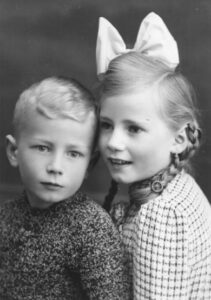

My sister, who is eleven months older, and I were born there. But my mother, also a Westphalian from Erwitte, was unhappy and homesick in Braunsberg, especially at a time, when the beginning of World War II was threatening mankind. I was less than a year old, when we moved to Kassel (Hessen), and so I cannot remember anything about Braunsberg.

KA: What are some of your notable memories of your childhood- especially in respect of elementary schooling, playmates, World War II etc?

Kassel after its destruction

FK: In Kassel, where I spent my early childhood (1938-1943) I experienced all the dangers and cruelties of war. Every night, when the air raid sirens howled, my mother roused me from my deep sleep and carried me in her arms to our cellar, the air raids shelter, where I experienced the hitting of the bombs in our immediate vicinity. We hoped and prayed that our house was saved. Such situations probably shaped my attitude towards life and death in later life. For me, life became something temporary, and every morning in Kassel meant that I was given a new day (there were no air raids during the daytime). This attitude was reinforced by a phrase my mother used to say when she put me to bed at night: “Good night until tomorrow, if we survive the following night”.

F.K. in Kassel

I had no clear attitude towards Hitler’s National Socialist Party. I did not understand that we lived in an unjust dictatorship and did not hear about Hitler’s cruelties. Nevertheless, I suffered from some influences of this regime on everyday life of a four-year-old boy. My parents had resolved that my sister and I went to a kindergarten. On the first day, my mother gave me one sandwich in a brown shoulder bag that I had to give to the kindergarten teacher. When all the bags were distributed one by one for lunch, I did not pay attention and asked for mine later. She gave me the bag and, for my lack of attention, a heavy slap in my face. I never went back to a kindergarten.

F.K. and his sister in 1943

When the air raids on Kassel had become unbearable, my mother followed my grandmother’s advice to move (without furniture) to the small town of Erwitte, where bomb attacks were not worthwhile for the Allied Forces.

I spent my primary school years in Erwitte. The lessons, which were not very pupil-centred, were probably in line with the attitudes of the ruling Nazi regime. I hated my four years at primary school, and every morning I went to class with an oppressive feeling. During the dictation of a German text, for example, the teacher was constantly looking over my shoulder and as soonI made the first mistake, I was beaten. In situations like this, I harboured the desire to become a teacher myself later on and do everything better.

F.K’s school class in Erwitte

In physical educations, as well as in situations outside of school, we often heard slogans from the Nazi era such as: “Praised be what makes you tough” or “What doesn’t kill us only makes us tougher”. Teachers probably also had the task of producing suitable human “material” for wars of future generations.

Erwitte

KA: What important values did you learn at home and how were these values imparted to you?

FK: I only mentioned my mother earlier, because my father had been conscripted into Hitler’s army, and he spent most of the wartime in France that had been occupied by the Germans. My mother was a very religious woman. She attended a Catholic mass-service at 7 a.m. nearly every morning of her life. So, my sister and I grew up in a very Catholic atmosphere, that was not clouded by any religious doubts that arose in later times.

KA: What memories do you have of your secondary education in terms of friends, favourite teachers and subjects, and your aspirations at the time.

F.K.: Because my family had to move frequently, it was often difficult to find good and lasting friendships. In Erwitte, my cousins were my closest friends, and we all lived together as part of a large extended family. It was only in Essen that I found lasting friendships with classmates from school—many of whom I am still in contact with, as far as they are still alive.

My favorite teachers were those who refrained from corporal punishment and offered engaging lessons. Some history teachers had a profound influence on my worldview and became role models for me when I later became a history teacher myself.

Alfred-Krupp-Gymnasium, Essen

School class of Essen

Our whole family was happy when my father came home unharmed from the war in 1945. He found a good job in his profession at the Federal Railway Directorate in Essen (Ruhr area), where he also moved into his own flat. Apart from the weekends, I lived in a family without my father again until we moved to Essen in 1948. Here I attended the Alfred-Krupp-Gymnasium, a school that emphasised the teaching of natural science. I immediately made good contact with my classmates (only boys), and most of the teachers were competent and friendly. My favourite subjects were physics (natural science) and history. I thought of studying electrical engineering at a technical university later on and therefore chose “physics” as my special subject in the Abitur (final examination). I also considered teaching at a senior secondary school, but my two favourite subjects (physics and history) did not go well together as a combination for teaching.

My full enthusiasm at that time, however, was dedicated to ethnology, although this subject was not taught in schools, and the career prospects were considered poor.

My interest in non-European, tropical continents (first it was South America, then Africa) can be traced back to my primary school days, when Catholic missionaries told us about their experiences in tropical countries. In my early teens I started reading adventurous novels and travelogues with traces of ethnological descriptions. Like most young people of my generation I Ioved reading books by Karl May dealing with American Indians and their heroic lives. Some years later, I read all the ethnological works that the Essen public library could offer, especially Leo Frobenius, Wilhelm Schmidt and his followers, but also general cultural and historical works e.g., Oswald Spengler, Arnold Toynbee and Karl Jaspers.

During my secondary school years, I often wondered how I could combine my love and knowledge of ethnology and future exams in this subject with a promising career.

KA: Kindly share your recollections of some major incidents during your time at the University of Munster. How did you develop your interest in Anthropology?

FK: After leaving secondary school in 1957, I chose English, history and geography as my subjects for a future teaching career. When I began studying these subjects at the University of Münster (Westphalia) it was not yet possible to study ethnology there. Nevertheless, I had decided to make Africa the focus of my ethnological work, though at that time it was more of a hobby-like occupation. My particular attention was focused on Arabic-speaking North Africa. This began in my secondary school days (1955) when I travelled alone across France and Spain and visited Morocco, which was still under Spanish and French colonial rule at the time. It was difficult to enter Morocco because there was still a civil war going on after the French had deposed Sultan Mohamed V and installed a ruler to their liking. This meant that I was only able to visit Ceuta and Tetuan, but it was enough to convince me that somewhere and somewhen I had to conduct ethnological studies in Northern Africa. Therefore, I started reading literature about North Africa and learning Arabic.

Colleagues of the Institute of Ethnology with Prof. Albert Awedoba (Institute of African Studies, Legon) and his wife as guests

In 1965, the Institute of Ethnology was founded at the University of Münster, and Prof. Dr. Rüdiger Schott from Bonn was appointed as its first director. A short time later, I sat opposite him in his office and explained to him that I wanted to study ethnology under his supervision. He was pleased about my interest, but pointed out that the career prospects in this subject were very poor. He was only relieved when I replied that I had already a profession and was also financially independent as a teacher.

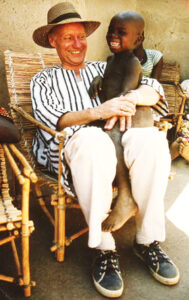

Prof. Schott in Ghana

I later explained to him that I would like to do a doctorate on a Berber group. Here, too, I received a sobering answer. I would have to learn or complete my knowledge about the following languages, which was probably not possible alongside my full-time teaching job:

– French, which I spoke very imperfectly at the time, because I had not learnt it as a student,

– Maghreb Arabic, which is spoken in Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco, for example,

– Classical Arabic, in which the sources necessary for studying were written,

– The Berber dialect of the group I wanted to research.

When Prof. Schott saw my disappointment, he encouraged me to find a topic among the hospitable but still largely unexplored ethnic group of the Bulsa in northern Ghana, where he himself had just conducted his first field research (1967-1968). I immediately agreed and began to study the available ethnographic literature and learn the elementary basics of the Buli language with three more students of Prof. Schott (1968). I also started collecting material for my planned thesis “Intergenerational conflicts among the Bulsa”.

Part II: Teaching

KA: What do you recollect of your time teaching at the University of Cape Coast (1972-74)?

Prof. Peter Morton-Williams

FK: In December 1972, I arrived at the University of Cape Coast to take over the management of the Subdepartment of German (until 1974), which belonged to the Department of French. At the same time, I intended to collect material for my PhD thesis on several trips to the Bulsa, but also among the Bulsa living in Cape Coast. Even though ethnology/anthropology was not taught at the University of Cape Coast, I found an interested supporter of my work in the Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy, Prof. Peter Morton Williams, an anthropologist who had specialised in Yoruba culture.

KA: And after you left Ghana, what experiences did you have as a lecturer at the Institute of Ethnology, University of Munster, and the Aldegrever Gymnasium?

FK: After my return to Germany, I mainly focused on writing my PhD thesis. On December 2, 1976, I passed the oral examination (in German, Rigorosum) in the subjects of ethnology, English and history. Immediately after the exam, I received my first teaching assignments at the University of Münster, for example, on the topics “Religious Ethnology of West Africa”, “Divination in West Africa” and “Buli for Beginners”. I also held several museum internships, in which objects from my Bulsa collection were catalogued. Among my students was Elisabeth Tietmeyer (later professor and director of the “Museum Europäischer Kulturen”, Berlin), with whom I organised a travelling exhibition with tools and products of the Bulsa blacksmiths in 1992.

The Bulsa Exhibition in Münster

In 2005, together with Miriam Grabenheinrich, Sabine Klocke-Daffa and professors from the “Fachhochschule Münster, Fachbereich Design, Münster” (University of Applied Sciences, Department of Design), I organised an exhibition in the “Westfälisches Museum für Natukunde, Münster” and provided all the exhibited objects from my collection of Bulsa material culture (see Grabenheinrich et al. 2005).

All objects of my Bulsa collection were exported legally; some were gifts, while others were purchased. All of them were presented to museum officials (e.g., at Cape Coast Castle and the Bolgatanga Museum) to obtain permission for export.

During all my ethnological studies and activities, I enjoyed my job as a teacher at the Aldegrever Gymnasium in Soest and I had a good relationship with my students. Every morning I commuted from my home in Lippstadt-Benninghausen to Soest.

Students describing and cataloguing Bulsa objects

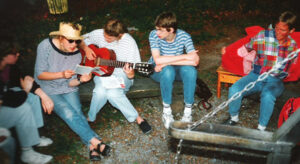

On the evening of a class excursion

Part III: An intellectual life with the Bulsa

KA: What do you recall about your first visit to Buluk, that is, the ancestral homeland of the Bulsa people in the Bulsa North and Bulsa South Districts? How did you immerse yourself among the Bulsa, from your first visit onwards and what motivated you to devote most part of your academic career to Bulsa society?

F.K. on a motorbike

FK: After my exams, my main concern was still centred on my field research among the Bulsa and the publication of the results. I carried out numerous field research projects, as outlined in the tables (see appendix).

My first visit to Bulsa land was accompanied by a severe malaria disease. Inexperienced in practical work and weakened by the disease, it was actually my companion Godfrey Achaw, Prof. Schott’s former assistant, who suggested which visits were obligatory and which work had to be done. Almost automatically, Sandema-Kalijiisa-Yongsa, Godfrey’s birth section, became my reference section for many years. All its inhabitants were extremely friendly and helpful, although understandably some heads of compounds (yeri nyam) were reluctant to share all their knowledge about their ancestors, religious rites, etc., with me.

KA: Did you face any initial challenges and if so how did you work out such challenges? What kinds of key collaborations have you had over the years with regards to your work among/with the Bulsa?

FK: Initially, there were problems with the realisation of my chosen topic “Intergenerational conflicts among the Bulsa…” In order to establish closer contact with the younger generation, I had taken on a teaching position at Sandema Continuation Boarding School (now Sandema Senior High School). There I realised that these conflicts were not very pronounced among the Bulsa (1973), mainly because many young people left home early to attend a boarding school or take a job in a larger city.

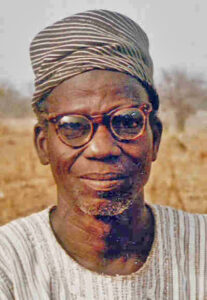

Leander Amoak

At the boarding school, my colleague, the arts teacher, Leander Amoak, immediately got in touch with me. He asked me to take part in a ma-bage ritual, in which the shrine of Leander’s paternal grandmother was relocated from Badomsa—where she had lived and died as a married woman—to the Fumbisi Chief’s compound, her birthplace (cf. Kröger 1978, 1982, and 2003).

As I wanted to devote all my time to the subject of my thesis, I declined his invitation. But Leander persisted, and on August 16, 1973, I saw the ma-bage announced ritual, which was of great importance for my research and which I was not able to observe again in later times. In many publications, I dealt with this ritual. It is probably the most important ritual event that renews the numerous matrilineal ties including the previously little-observed marriage bans of a compound.

After my first visit to Leander’s compound, others followed, until eventually more pages in my field book were filled with notes on rites than on the unproductive topic of “Intergenerational conflicts”. I then decided to change my PhD-topic to “Rites of passage among the Bulsa”. My supervisor, Prof. Schott, immediately agreed.

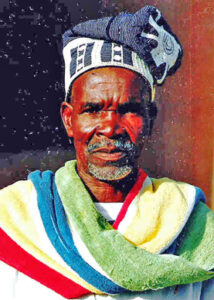

Anamogsi Anyenangdu

In 1984, I planned to stay in a traditional compound in Badomsa for at least a week, so I asked Mr. Leander, who himself lived in a more modern house in the centre of Wiaga, whether there was a landlord (yeri-nyono) in Badomsa who would let me participate in traditional life in his compound for a few weeks. Leander’s answer was astounding: Each of the Badomsa compounds would be happy if I moved into their house for a few weeks. So I had a choice of 51 compounds. I chose Anyenangdu Yeri, one of the largest compounds in the section with its yeri-nyono Anamogsi, who, as an earth priest (teng-nyono), elder (kpagi) of a part of Badomsa as well as a traditional healer (tiim-nyono), could give me insights into important cultural branches of the Bulsa.

After a short stay in 1984, Anyenangdu Yeri became my permanent residence until the end of my research period (2011).

I would describe Anamogsi, who had never attended any school, as the ideal informant and collaborator. If my publications on the Bulsa found a certain recognition in the professional world, this was largely due to Anamogsi. He allowed me access to all rituals, sacrifices and profane acts as a matter of course, and he even expected my participation. In order to give me more leeway for photos during sacrifices, he usually operated my tape recorder alongside his sacrificial activities. These freedoms applied not only to his own, but to almost all compounds of Badomsa.

In the last years of my research, he had even adopted me as his eldest son, which meant privileges as well as duties. For example, I was entitled to a front leg for every animal sacrifice to the Pung Muning earth sanctuary (tanggbain), and when Anamogsi was not at home and a foreign visitor arrived, he was referred to his eldest son (i.e., me). I am very grateful to Anamogsi for allowing me in 1994 to take an inventory of all the material objects in the individual households of his compound. This also applied to the windowless and dark ancestral room (kpilima dok), whose ritual objects I was allowed to place in the main courtyard (Ama dok) for photographs.

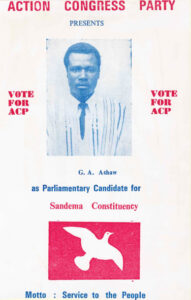

Achaw as a parliamentary candidate

When I look back today on the work of my assistants, or rather collaborators, I realise that they were often not just helpers and educators, but often the driving force or even the initiators of certain research events. Godfrey Achaw introduced me to his birth section as a matter of course, and Anamogsi thwarted my own plans when he considered an event to be more important for my research. The soothsayer Akanming decided to make me his successor without consulting me, after all his sons showed no interest in becoming a diviner. I had to take part in all wen-piirika rituals without fail, and he was annoyed when I preferred to attend another coinciding event. He gave me regular lessons on divination techniques, in which I learnt the names of all the code objects in his divination bag (baan yui) (cf. Kröger 1992).

Two terracotta heads in a stone heap (Zamsa)

Leander Amoak tried hard to take the lead in carrying out my research projects. When I met him one morning to pay a visit to the Wabilinsa section as previously planned, he told me “Today we are going [on one moped] to Tandem-Zamsa, where the ancestors are worshipped in stone figures [correctly: terracotta figures]”. I was a bit annoyed at first. Later, however, I realised that this was one of my most important visits to another village, as it ultimately led to the discovery of the Komaland terracottas, which attracted a lot of attention in various disciplines of the professional community.

KA: With your research visits over the years, what have been some of your key findings and insights?

FK: Many of my publications have a predominantly descriptive character. This should not necessarily be seen as negative, as the descriptions provide sources for further analytical research and also give many educated Bulsa, who are alienated from their own culture, a better insight into the religion, history, and society of their fathers. In my work, however, I was also able to gain some new insights through analytical methods. These include:

a) The possession of ancestral shrines potentially rotates through all the compounds of a lineage over time (Cf. Kröger, 1982 and 2003). Their owner is the elder (kpagi) of all descendants from the ancestor in question. It is also important to note that ancestor worship has enormous economic significance, because the land and livestock acquired by the ancestor also rotate among all of his descendants along with the shrine.

Yaw Akumasi

b) Together with my assistant at the time, Yaw Akumasi, I worked out the lakori principle for ritual life. It regulates the extent to which the course of a ritual must be oriented towards those practised in the past and how changes can nevertheless be made possible (Kröger 2012).

c) By analysing the corresponding sources of Bulsa history, I was able to determine the point in time when Atuga entered Bulsaland. Since all of the numerous versions about his immigration assume that his original home was Nalerigu and not Gambaga, this means that the founding of the new Mamprusi capital Nalerigu (about 1760) provides a terminus post quem, that is,the earliest possible time, for Atuga’s immigration (cf. Kröger 2013: 77). According to Ollivant (1933: 3), Atuga was a grandson of Na Atabia, who changed his residence from Gambaga to Nalerigu. This means that the immigration of Atuga’s Mamprusi group took perhaps place at the end of the 18th century.

d) Another important discovery extends beyond Bulsaland.

Crossing the Sisili River for Yikpabongo

A Komaland Janus figure

After I had documented some very old terracottas in Tandem-Zamsa in1982, I visited Yikpabongo (Komaland) on July 7 and 8, 1984, where the inhabitants and foreign dealers had excavated terracottas of the Zamsa style. Immediately after this visit, on July 16, 1984, I reported the find to the Department of Archaeology at the University of Ghana, Legon and thus initiated the first excavations by Prof. James Anquandah-the first trained Ghanaian archaeologist- in 1985. Since I was the first to publish on these terracottas (1982) and had the first TL-dating carried out at Heidelberg, Germany, in 1984, I have generally been regarded as the scientific discoverer of the Komaland terracottas (see Kröger 1982 and 2016a, and 2016b).

KA: From all you have explored, learnt, and shared, how will you describe the Bulsa and their culture? What are some distinctive characteristics of Bulsa people and their culture?

FK: When a foreigner visits Bulsaland for the first time, he first experiences the Bulsa as hospitable, cheerful, and helpful people. This was also my experience.

But I believe that I have noticed a characteristic trait that is generally perceived as less typically African by strangers. The Bulsa try to organise their religious and social relationships according to strictly rational criteria in a more or less complex system, and as far as I know, this happens to a greater extent than among the neighbouring ethnic groups (for example, the Tallensi and Koma).

Let us take the exact knowledge and veneration of their ancestors as an example. While the Tallensi merge older ancestors together in a common shrine (external boghar), and in the Koma harvest sacrifices usually only ancestors who lived a few generations ago are considered, old Bulsa men know or knew their ancestors by name for about 13 past generations, i.e., usually up to Atuga, who immigrated centuries ago. It would be quite easy for me to unite people from Sandema-Yongsa and Wiaga-Badomsa, for example, in one genealogical table. Knowing the names is not an end in itself. They have important functions in the system of rotating ancestral shrines, which have not only religious but also social and economic effects (see Kröger 1982 and 2003).

This adherence to a systematically defined system of rules is also evident in other areas of life, for example, in the performance of sacrificial acts according to the lakori principle (Kröger 2012). In order to compensate for a violation of this principle, which is based on previous similar rituals, not only sacrifices to the deceased must be made up for, but also the same grave goods must be placed in the old graves. I have seen several graves of the deceased being reopened and a smock (garuk) added to each one, as these older dead men were buried unclothed, while at the actual burial, the deceased had been laid into the grave in a smock.

Even mundane acts, such as greetings and thanksgiving, are based on long-established traditions. At a major ritual event attended by guests from various sections, there was a discussion in the kusung (traditional shed for meetings and resting) lasting almost half an hour about who should officially greet whom first.

There are also long-established principles and rules for the creation of material cultural objects. For example, when building a traditional compound, which in my opinion is one of the greatest pieces of art of the Bulsa, the ancestral room (kpilima dok), the central granary (bui), the main entrance (nansiung), the ancestral shrines (bogluta) in front of the compound and the meeting room (kusung) should be situated in one line facing west. Other large shrines, such as earth shrines (tanggbana), must not be located on the continuation of this line.

The systems and principles that function according to strictly rational criteria, as listed above, and which sometimes even appear somewhat pedantic to the European observer, do not correspond to the views of some former European writers, who regard a motivation that is irrational for Europeans and arises spontaneously from the moment, as an important principle of actions for many Africans.

KA: From your perspective, why is it important to preserve Bulsa culture and how should we go about it?

FK: The question of why it is important to preserve the Bulsa culture can be dealt with from two different angles. From a global point of view, this is important for recording cultures spread across the whole world. It is the only way to fully answer the question, “What is man [human] as a cultural being?” All non-European pre-industrial cultures contribute to this and should therefore be preserved in their current form in detailed records.

A second argument relates to the Bulsa themselves. Every ethnic group, whether large or small, needs an understanding of itself in order to survive. This is the only way to develop a sense of healthy self-confidence without arrogance.

Therefore, all modern movements and organizations that contribute to this (for example, the Bulsa Heritage Cultural Society, Buli Zamsika and other Bulsa social media groups) should be actively supported through participation in discussions, collaboration, and/or donations. All efforts to commemorate the historical past and present cultural elements to the local population or foreigners should be encouraged (for example, in large festivals, exhibitions, a new Bulsa museum, etc.).

KA: Considering the work you’ve done so far, what aspect of Bulsa society would you recommend warrants further studies, especially by the present and next generation of researchers, from a multidisciplinary perspective?

FK: I think two fields of Bulsa culture need special consideration by the present and next generations of researchers:

a) More attention should be paid to the so-called Southern Bulsa (who are non-Atuga-bisa). I, and also Prof. Schott, were criticized for having neglected the Southern Bulsa in our research, and this critique is certainly justified. I tried to make up for this shortcoming to a small extent by dedicating the issue no 10 (2017) of the Buluk magazine to the South Bulsa.

Cultural differences between even neighbouring Bulsa villages are often considerable, and a more intensive study of the south could reveal completely new aspects of Bulsa culture. In the history of the Southern Bulsa, for example, it still seems largely unclear whether the village founders or founders of particular sections emerged from the endogenous population, came to Bulsaland in the company of Atuga or from a foreign ethnic group. Filling such research gaps is certainly a matter of great urgency, as more and more old men with excellent knowledge of history no longer pass it on to the next generation in time before they die.

b) A second necessary area of research relates to the recent cultural development of all Bulsa and will continue to exist in the future. All societies on our planet have been subject to constant change, which has accelerated in the last hundred years. Even Bulsa, who value their old traditional culture cannot escape it. This change is not a one-off, short-term, and all-encompassing phenomenon, but affects some elements while others remain initially unaffected by it. In still other cases, cultural elements are adopted without the traditional ones being abandoned. This process of change deserves to be studied with great zeal by cultural scientists, and perhaps Bulsa researchers are better suited for this than foreign ones.

KA: Of all the work you’ve done in terms of the numerous publications (books, articles etc), collected material culture, Buli-English dictionary among others, what would you want to be remembered for as your legacy?

FK: It is difficult to say which of my publications has the greatest scientific value. It is likely that the Buli-English Dictionary in its 1st and 2nd editions will have the greatest sustainability. While other books and essays only deal with partial aspects of Bulsa culture for a limited group of readers, the dictionary, especially in its digital second edition as an app for Android smartphones or tablets (Buli A-Z, Buli Dictionary), is more likely to meet the needs of larger groups who have not been able to expand their Buli vocabulary due to a long absence in a non-Buli-speaking environment.

I am sure that in the future such a dictionary will be published by other authors who will use more modern methods, for example, to determine pitches. But it is probably difficult to completely disregard the data in my present dictionary.

KA: Many thanks, Franz. Indeed, this has been a very insightful and inspiring conversation.

References

Grabenheinrich, Miriam and Sabine Klocke-Daffa

2005 15 Frauen und 8 Ahnen. Leben und Glauben der Bulsa in Nordghana. Münster: Institut für Ethnologie [Handbook of the Bulsa Exhibition].

Kröger, Franz

1978: Übergangsriten im Wandel. Kindheit, Reife und Heirat bei den Bulsa in Nord-Ghana, Kommissionsverlag Klaus Renner, Hohenschäftlarn near München (420 pp.).

—, 1982: Ancestor Worship among the Bulsa of Northern Ghana. Klaus Renner Verlag, Hohenschäftlarn near München (116 pp.).

—, 1986: ‘Der Ritualkalender der Bulsa (Nordghana)’. Anthropos 81 (4/6), pp. 671-681.

—, 1992: ‘Das Schmiedehandwerk der Bulsa in Nordghana.’ In: E. Tietmeyer, Zwei Eisen im Feuer. Schmieden im Kulturvergleich. Begleitbuch zur gleichnamigen Wanderausstellung des Westfälischen Museumsamtes, Münster, pp. 11-32.

—, 1992: Buli-English Dictionary. With an Introduction into Buli Grammar and an Index English-Buli. Lit Verlag Münster and Hamburg (572 pp.).

— , 1992: Schwarze Kreuze und Wahrsageobjekte: tote und lebende Symbole der Bulsa, in: W. Krawiets, L. Pospišil und S. Steinbrich (Hg.), Sprache, Symbole und Symbolverwendungen in Ethnologie, Kulturanthropologie, Religion und Recht. Festschrift für Rüdiger Schott zum 65. Geburtstag. ´p.. 93-107, Berlin

—, 2001: Materielle Kultur und traditionelles Handwerk bei den Bulsa (Nordghana). Forschungen zu Sprachen und Kulturen Afrikas (ed.. R. Schott), 2 vol, Münster and Hamburg (1109 pp.).

—, 2003 ‘Elders – Ancestors – Sacrifices: Concepts and Meanings among the Bulsa’. In: Franz Kröger and Barbara Meier: Ghana’s North. Research on Culture, Religion and Politics of Societies in Transition, Peter Lang Verlag, pp. 243-262.

— 2012 Die dauerhafte Etablierung von rituellen Abweichungen. Das lakori-Prinzip bei den Bulsa Nordghanas. Anthropos 107, pp.1-12.

— 2013 Who was this Atuga? Facts and Theories on the Origin of the Bulsa. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and History. No 7, pp. 69-88.

— 2016a The Komaland Terracottas – Description, Classification and Analysis. www.komaland.com

— 2016b Die Komaland Terrakotten. Beschreibung, Einordnung und Analyse / The Komaland Terracottas. Description, Classification and Analysis. In: Hans Scheutz (ed.), Die vergessene Kultur. Terrakotten aus Nordghana / The Forgotten Culture. Terracottas from North Ghana. Wien and Münster: Lit Verlag, p. 8-63.

— 2017 The Earth Cult of the Bulsa (Northern Ghana). Special Issue of Buluk, Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society (78 pp.)

Kröger, Franz and Ben Baluri Saibu

2010 First Notes on Koma Culture. Life in a Remote Area of Northern Ghana. Münster, Berlin: LIT-Verlag, Brunswick, New York: Transaction Publishers (568 pp.).

Ollivant (= Olivier? District Commissioner of Navrongo and Builsa Districts)

1933 A short history of the Buli, Nankani and Kassene speaking people in the Navrongo area of the Mamprusi District, (unpublished manuscript).

Perrault, P.

1954 History of the Tribes of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast, St. John Bosco’s Press, Navrongo.

Schott, Rüdiger

1977 Sources for a History of the Bulsa in Northern Ghana. Paideuma 23, pp. 141-168.

Appendix

- Editors and Copyrights

- Editorial

- Two Sons of Buluk ordained in Wiaga to the Catholic Priesthood

- Bulsa schoolgirls sew sanitary pads

- Margaret Akanbang – The Mother of Doctors

- Animals, a Benefit for the Bulsa

- Events

- Elections 2024

- Joseph Aduedem: Gbanta Bogka – A Journey into Bulsa Divination Practices

- Obituaries

- Darius Adjong’s PhD thesis

- A German Anthropologist among the Bulsa: A Biographical Conversation

- POEMS

- MAIN FEATURE: BULUK OVER THE LAST HUNDRED YEARS