Franz Kröger

HISTORY OF THE BULSA – WITH SPECIAL CONSIDERATION OF THE SLAVE WARS

Introduction

Since researchers of African history have included oral sources in their investigations, a discussion has arisen on how much their truthfulness can be assessed. Certainly, these oral traditions, passed down from one narrator to another over generations, were subject to considerable changes, omissions, and additions, while documents, letters, diaries and reports written down centuries ago remain unchanged. On the other hand, with regard to the colonial history of Ghana, these written sources express only statements from the point of view of one party, namely the British colonial rulers. The views and feelings of those affected, here the Bulsa, find a proper expression in oral traditions, where also many individual destinies, anecdotes and other details have entered the main text.

In the present study, I have tried to combine oral traditions with data stored in archives. What I have written here about Bulsa history is mainly the result of the cooperation with old Bulsa people and their willingness to disclose all their knowledge about traditional Bulsa history. Particularly noteworthy is the late Nab Dr. Ayieta Azantilow of blessed memory, who was filled with a depth of knowledge about Bulsa history, and who gave me and the late Prof. Rüdiger Schott all the attention we needed (Cf. Schott 1977).

Further knowledge about Bulsa history was provided by the National Archives in Accra and other archives (endnote 1). The texts found there about our subject were almost exclusively written by British colonial officers. As in almost all historical sources, they were also fraught with a certain amount of prejudice, which means that most events were seen through the eyes of colonialists. Nevertheless, these archive sources are very important because they provide a

chronological order by mentioning the year after Christ (AD). These numbers are the backbone of any historical representation.

I would particularly like to draw attention to the British administrative and military officers

who, in the early years of the twentieth century, took the trouble to preserve historical knowledge through dialogue with elder Bulsa and other Africans. Although they usually did not have any historical or anthropological training, their research methods had an advantage over today’s interviews: At that time there were many more old men with great historical knowledge among the Bulsa informants. Above all, many of their informants had witnessed important events themselves. Mr S.J. Olivier (or Ollivant), the British Commissioner of the Navrongo District, which, at that time, included the Bulsa Native Authority, got information from Babatu’s horse boy who had taken part in his master’s battles and raids. Malam Abu, who in 1914 wrote the first comprehensive report on Babatu’s conquests, had always been a close companion of Babatu. The Malam wrote his book in Hausa using Arabic characters. In short chapters, he described Babatu’s attacks on various villages, usually in a matter-of-fact style. I could make use of Malam Abu’s book after it had been translated into English in 1992 by Stanisɫaw Piɫaszewicz.

Regarding the contents of the following article, I would like to give a brief outline of the whole Bulsa history, but will concentrate mainly on facts and events that are associated with Babatu’s raids, the reaction of Bulsa to these attacks and the defeats Babatu had to suffer in the battles of Sandema and Kanjaga.

Early History

An important question about the beginnings of history in the area now inhabited by Bulsa is how long people have been living here and who these people were. No archaeological excavations have ever taken place within the two Bulsa districts. Therefore, we can only adopt research data from other parts of Northern Ghana to answer our question.

In the millenniums before Christ (BC), the Sahara, which had not been completely infertile before, became dryer and dryer making it difficult for people to live there. The consequence was a migration, particularly of cattle-herders, from the Sahara to the south, which in some way might have also affected the Bulsa area.

We do not know much about the original inhabitants of this area, but they were probably hunters and gatherers. Many Bulsa told me that these people liked to live in caverns, and some Bulsa even claimed that they came out of the earth itself, which probably means that they were the original inhabitants.

In the absence of excavation results for the Bulsa area, I wish to mention two objects which have been in use among the Bulsa and other ethnic groups for many centuries up to even very recent times and which were also found in excavations of the early Iron Age and Kintampo culture (endnote 2) of middle and southern Ghana.

a) Twisted iron bangles with or without loops (Buli bang gbing respectively bang) were excavated near Daboya by Shinnie and Kense and, according to the archaeologists, they belong to the early iron age (1988: 203 and 208). They are known from other excavations in Ghana and are distributed over large parts of West Africa.

In his analysis of the objects excavated at Yikpabongo (N.R.), J. Anquandah writes about these iron bangles (1998: 97):

The twisted iron lightweight pendant/bangle with loops found in the excavations has a direct parallel in modern Bulsa culture and is known as Bang-gbin (fig. 6.16).

Bulsa twisted iron bangle with loops (bang gbing)

b) Stone bracelets (Buli nisa pung), worn on the right upper arm by Bulsa until recent times, were found in Daboya, too. Apart from bracelets made from a greenish stone, two pieces are described as having been made of a “black stone mottled with white”. Furthermore, “All the bracelets… are triangular in section and have been ground smooth…” (Shinnie and Kense 1988: 178). Polished marble arm-rings, which are D-shaped in cross-section are also known from Kintampo sites (Ozanne 1971: 42).

Bulsa stone armlet (nisa pung)

In the last phase of the Kintampo culture (beginning around 150 BC) metallic iron was extracted from iron ore as industrial centres in the Brong Ahafo Region and Northern Ghana have proved. For producing iron, the Bulsa used their local iron ore (balerik, a type of ‘gravel’), which is found in big quantities in many parts of the Bulsaland. Their technique was only given up some decades ago, when scrap iron as material for new iron objects was easier to get (cf. Kröger 2001: 404-409). We may assume that producing metallic iron from iron ore had a very long tradition here, although there is a lack of any exact dates obtained through excavations. In some Bulsa villages, iron-ore slags are scattered on the farmland so densely that the farmers had to collect and heap them up (see photo).

Heaps of slags on a field in Kadema

Around 1000 AD cowrie shells (Buli lig-piela) were introduced into West Africa and soon became not only an element for decorating both the human body and material objects, but also a widespread currency in West Africa. The first cowries (Cyprea moneta) had to be transported from the Maldives by way of North Africa so that their value was not mainly based on their material but on the costs of their long transport. In the 19th century, large quantities of a slightly different type of cowrie (Cyprea annulus) were introduced by European merchants from East Africa and were also accepted by the West African population as their currency (Cf. Johnson 1970 and York 1972).

Among the modern Bulsa both types of cowries can be found, but we do not know anything about their origin in this area, because cowrie-money circulated over large areas of West Africa.

Archaeological excavations closest to the Bulsa were carried out by J. Anquandah and after him by B. Kankpeyeng among the Koma (N.R.). In Yikpabongo Anquandah found both types of cowries, Cyprea moneta and Cyprea annulus (Anquandah 1998: 77-78).

The large volume of imported cowrie shells caused their value to depreciate so that higher units of payments were necessary, e.g. baskets or bags of cowries. The Buli term boosa (or boorisa), in the past corresponding to 200 cowries or one bag, is still used at Bulsa markets. Today one borik (singular of boosa) equals two Ghana Cedis.

The Mamprusi and Atuga

From around the 9th century onwards, large and powerful kingdoms were established on the southern edge of the Sahara. The first was Gana, after which the modern state of Ghana is named. Old Gana’s economic wealth was a result of its location where gold from the coastal areas was exchanged for salt from the Sahara.

After the 15th century, new kingdoms were created in what is today Northern Ghana including the Dagomba, Nanumba and Mamprusi. The latter kingdom had a strong influence on the people who lived in Bulsaland. In the 17th and 18th centuries there was apparently a certain dependence of this area on the Mamprusi. More important for the historical self-identity of the Bulsa, however, was another event: After a family dispute, a Mamprusi prince immigrated with his family and a small entourage into Bulsaland where he probably first lived south of Sandema in an area that is still called Atuga Pusik, close to today’s Senior High School. Almost at the same time, other Mamprusi princes left the kingdom after either an argument with their father or in search of land. Ali, son of the Mamprusi king Atabia, took Bawku facing little resistance from the local inhabitants. Furthermore, Mosuor, the ancestor of the Namoo, a Tallensi clan, was a member of the Mamprusi royal family. He, too, had to flee because of a conflict. After his death, three of his sons founded the Tallensi villages Yamelog, Sie and Biuk.

The question when Atuga come to Bulsaland can perhaps be answered today with a certain probability. First of all, it is noteworthy that in all the eight versions of the story that I could gather about the immigration of Atuga and his family among Bulsa informants (Kröger 2013: 69-88), the Mamprusi Prince Atuga came from Nalerigu and not from Gambaga. Around 1760, the Mamprusi King Atabia (Atabea or Zontua) had moved his residence from Gambaga to Nalerigu, and made it the new capital of his kingdom. The departure of Atuga must have taken place after that date.

In all my Bulsa interviews I could not establish anything concrete about Atuga’s royal father. In the National Archives of Accra, however, I found a report written before 1933 by the British officer S.J. Olivier, who had collected data on Bulsa history. He was told that Wurungwe (whose name also appears as Wurume), together with his son, Atuga, had left Atabia, the Mamprusi king, in search of land (Kröger 2013: 73). According to Perrault, a Rev. Father at the Catholic Mission of Navrongo, Atabia reigned from 1760 to 1775 in Nalerigu (1954: 47). This means that the immigration of Atuga and his family to Bulsaland might have happened around 1770 or 250 years ago.

According to Olivier (1933: 2) Atuga married the daughter of his Bulsa friend, Awulong, and had four sons: Akadem, Asam, Awiag and Asinieng. These sons settled in the villages of Kadema, Sandema, Wiaga and Siniensi. Atuga’s ancestral shrine is venerated in Kadema, where his eldest son had lived and died.

The Consequences of Atuga’s Immigration

The lasting cultural and political effects of Atuga’s and his family’s immigration are not extraordinarily great. In most of the Bulsa villages, they established a kind of chieftaincy with court officers if it hadn’t existed before. In the pre-Atuga Bulsa society a very important power – particularly in the religious sphere – resided with the earth-priest (teng-nyono). In the secular sphere of the society, the “big men” (i.e. the rich and/or influential people) might have occasionally obtained chief-like positions, particularly if they were also the commanders of the temporary village armies.

The bulk of Bulsa culture, e.g. material objects, agriculture, animal husbandry, lineage structure, religion as well as the Buli language remained nearly unchanged. The office of the teng-nyono (earth-priest) was furthermore exercised by men of the original population.

There is an anecdote, told by Olivier (1933: 2), demonstrating that the Atuga-bisa, i.e. the children or descendants of Atuga, even adopted customs hitherto strange to them.

After having settled between Wiaga and Sandema, Atuga met a man called Awulong who spoke a language called Buli… These two became friends but Atuga, being a Mamprussi, was not a dog-eater. Awulong was, and he asked Atuga to join in eating a dog to celebrate his arrival. Atuga agreed and swore an oath to this effect: “Now that I have eaten a dog, I am no longer a Mamprussi and none of my descendants shall ever set foot in Mamprussi country again on pain of death”. This story has been handed down to the present day and no descendant of Atuga has ever been into Mamprussi unless ordered to by the British to a conference at Nalerigu or for some other reason.

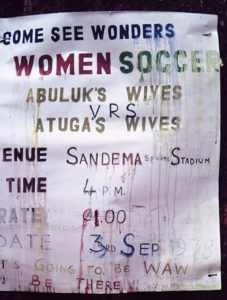

Announcing a football game in Sandema (1978)

Historically more important than the enculturation of material things and customs was the relationship between the two groups of different ethnic origin. Among the Tallensi, the descendants of Mosuor, called Naamos, and those of the original population, the Talis, have formed two different clusters of people who have remained separate to this day. According to Meyer Fortes (1949: 2-3), “the two groups never combined for defence or attack on neighbouring tribes, but were traditional enemies. War sometimes broke out…”

The situation among the Bulsa was and is quite different. Although conflicts between small groups of Atuga-bisa and original Bulsa might have taken place in early times, there has never been a war between the two clusters of population. And in times of danger, members of both groups fought side by side. The reason for this relatively peaceful cooperation might be found in their very close emotional and local co-existence.

There is a legend that Atuga’s young male relatives even herded their cattle together with native Bulsa boys. Above all, it was the intensive intermarriage between the two groups that melted them together. I don’t think that any Bulsa can say that all of his male and female ancestors were either completely Atuga-bisa or Non-Atuga-bisa.

On September 3rd, 1978, there was a football match in the then new sports-stadium of Sandema: The wives of Atuga-bisa played against the wives of the Non-Atuga-bisa (see photo). If we consider that part of the wives of the Atuga-bisa might have been Non-Atuga-bisa, and part of the wives of the Non-Atuga-bisa were Atuga-bisa, we can understand the confusing complication of the intermingled teams. One young Bulsa told me that he is at a loss, because he does not know which team he should favour. The solidarity of the two groups was displayed in a significant political crisis that jeopardized the existence of both groups, namely Babatu’s slave raids, which are the subject of our next historical description.

The Zabarima Slave Raids

The first event that included the original cause for the slave-raids was a conflict between the Dagomba and the Ashanti. The Dagomba king, Na Gariba (1700-1720), was taken prisoner in Yendi and promised freedom upon the payment of 2000 slaves (Tamakloe 1931: xii). When he could not provide them immediately, the Ashanti allowed him to pay a certain number of slaves every year instead (endnote 3).

As the Dagomba were not willing or able to use people of their own kingdom, they started slave-raids among the ethnic groups north of them who had no strong chieftaincy with a large army and who were generally called Grunchi or Gurunsi. After some time, the Dagomba saw a chance to transfer these raids to another group of warriors, the Zabarima (Zambarima, Zaberma) most of whom were living in the Dagomba town of Karaga.

Something should be said about the origin of these people. They came from the region of Niamey in the modern state of Niger. In the early time of their stay among the Dabomba, they were traders in horses, cola-nuts and slaves. Other were mercenaries, Malams or scholars who tried to spread a militant form of Islam. Among the Zabarima there was one very respected scholar named Alfa Hano who became the spiritual leader and, later, also the secular leader of all Zabarima (endnote 4). When a new slave-raiding expedition started in 1856 (endnote 5), a group of Zabarima under Alfa Hano accompanied them. After a joint expedition that included fighting in the Dagomba army, the Zabarima decided to stay in Grunchi-Land and live by raiding Grunchi villages (including the Bulsa).

Alfa Hano died after about three (Holden) or six (Tamakloe) years of leadership around 1870 (Holden 1965: 66), and Alfa Gazare became his successor. According to Holden (ibd.), “in probably less than ten years he laid the military and organisational basis for the Zabarima state (endnote 6). When Gazare was fatally wounded in a battle by a poisonous arrow, his two sons, Hamana and Babatu succeeded him. Later it was Babatu who became the most powerful ruler of the Zabarima and Grunchi-Land.

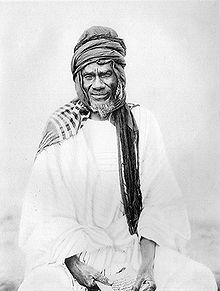

Samori Toure (Source: en.wikipedia.org)

What type of personality was this Babatu? It is a pity that, in contrast to Samori and even Babatu’s officer (and later enemy) Amaria, we have no photo of Babatu. At the very least, we know something about the clothes he was wearing. Before his death, Alfa Hano let his followers know that the Zabarima chiefs, from that point on, should wear outfits consisting of a white gown, a hat and a turban. Their clothes probably looked like those worn by Samori.

Babatu wore tribal marks invented by him. He believed it to be necessary and expected not only the leaders but also their soldiers and slaves to wear uniform marks. According to Tamakloe (1931: 49), Babatu’s marks consisted of “two parallel dotted cuttings from the temple down to the cheeks (both sides), with one cutting from the middle of nose on the right”.

As a devout Muslim Babatu invited several Malams of different ethnic origin to join him which, however, did not keep him from attacking other Muslims, e.g. those of Wa. Malam Abu, Babatu’s permanent companion, criticised this attitude vehemently and called him a “suppressor of Muslims” and also a “wicked ruler” in his book.

Babatu’s army, with its horsemen and soldiers equipped with muzzle loaders (Dane guns), was quite superior to the troops of the Grunchi who, by contrast, only fought on foot with bow and arrow and a war-axe or spear. In spite of this superiority, Babatu prepared his battles carefully.

According to one informant from Sandema, he sent an agent called Mohamed into the Bulsa villages he intended to raid. This man pretended to buy millet and to build a house in Bulsaland. After making friends with some important Bulsa, he inquired into the types of weapons they possessed and the strategies they used in battle. Later he reported everything to his master, Babatu, who reacted by providing leather clothes for his warriors.

Perrault (1954: 94) describes Babatu sometimes using a trick in his attacks in order to avoid bloodshed among his own soldiers. He used to send some of his soldiers to attack one village where they would fire only a few shots. When the surrounding villages heard this they would run to help their neighbours and while their able men were away, Babatu attacked the unprotected villages with his main force. He is said to have killed the old people and the young children taking the young adults to be sold as slaves, soldiers or, respectively, wives.

Before the victorious battles of Sandema and Kanjaga are described, it is necessary to say a few words about defensive measures carried out by the Bulsa (endnote 7).

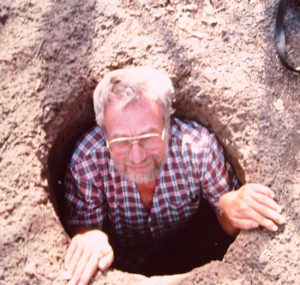

The entrance to Posuk Cavern

The Bulsa compound, surrounded by a high wall and buildings with only small windows, has fortress-like qualities. From the flat roofs of some houses, the enemy could be perceived very early. Furthermore, through using a particular communication system, neighbours could pass along warnings by shouting a message (wiik) from compound to compound. It was even more difficult for the raiders to approach and conquer a Bulsa compound if it had been built in a very rocky area or on a hill because it meant that Babatu’s horsemen could not move and operate freely. This might be the reason that we find quite a few abandoned settlements (Buli: guuta) from that time on stony hills, for example on Adakurik, south of Sandema and on Pung Muning in Wiaga Sinyangsa.

The hollow baobab tree in Wiaga- Sinyangsa (a tree of refuge)

Only a few fugitives could find refuge in a hollow tree. One of these refuge trees, a very big baobab, can still be visited in Wiaga-Sinyangsa, near Pung Muning (see photo).

In many historical sources about Babatu’s raids among the Grunchi, we find that the attacked people took refuge in caverns. The Bulsa, too, had caverns of refuge, but in their plan and construction they differed fundamentally from others. A relatively well-preserved example is the cavern called Posuk, situated to the south-west of Wiaga’s centre. In the time of Babatu, the cavity in the rocks was completely invisible from outside and people could enter it only through a shaft and a tunnel ending in the natural cave. Here the fugitives, especially old people, women and children, were crammed into this small room (Kröger 2008: 33).

Babatu’s Attacks

The Zabarima’s greatest power and sphere of influence was achieved under Babatu by the late 1880s (Holden 1965: 60). He did not rule over a well defined empire with fixed boundaries. Rather, there were towns and villages that had either been completely subdued by the Zabarima or constantly suffered from raids (such as the Bulsa). Babatu’s and his predecessors’ invasions and wars took place in an area ranging from Wa to Bolgatanga (Holden 1965: 69) and in the north it reached the territory of the Kipirsi and localities not far from Ouagadougou, while in the south, the kingdoms of Mamprusi and Dagomba put up a certain amount of resistance. Babatu had levied a number of Grunchi villages with a tax which promised a certain amount of security for them if they paid the tax in time. However, the Bulsa villages were probably not included.

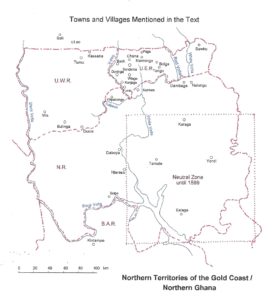

Most of Babatu’s raids had their starting point from his central camp, which was first located in Kassana (Kasena area, Ghana) and, later, in Sati or Seti (25 km northwest to Léo, Burkina Faso, see map). Here we will only deal with Babatu’s attacks on Bulsa villages. From Sati, Babatu carried out two major campaigns: one to Navrongo and one to the Bulsa.

Apart from Sandema and Kanjaga, the following Bulsa villages (among others) were attacked by Babatu according to oral and written sources:

• Chuchuliga: Babatu defeated an army consisting of unified warriors from Chuchuliga, Navrongo and Paga (Piɫaszewicz / Abu 1992: 84). This battle was probably part of his Navrongo campaign.

• Siniensi: After the conquest of Siniensi, there was a dispute between two Zabarima leaders. Babatu gave the village to a son of his predecessor, Gazari (Piɫaszewicz / Abu 1992: 98).

• Kunkwa: In a battle on a small river, the inhabitants of Kunkwa offered Babatu’s troops fierce resistance, and both Babatu’s son Ishaka as well as the chief of Kunkwa lost their lives. But in the end, Kunkwa was defeated (Piɫaszewicz / Abu 1992: 83).

• Fumbisi: Although the chief of Fumbisi sacrificed a white bull to his drum before the battle, he lost it and was killed (Piɫaszewicz / Abu 1992: 83).

• Wiesi: The conquest of Wiesi and Kunkwa took place “four or five years before the whites came to fight the Zabarimas” (Holden, p. 75).

The Battle(s) of Sandema

Quite well known among interested Bulsa is the battle of Sandema, which will be treated here in detail. There is, however, contradictory information about the site where the battle took place. Was it in Fiisa near the big tanggbain (earth-shrine) of Azagsuk? Or was it south of Sandema, near a place called Akumcham (of Atuga Pusik) not far from the present Senior High School, where, after the battle, the Bulsa hung the dead body of one of Babatu’s wives on a sheabutter tree (cham)?

In August 1973, the late chief Azantilow gave me information about the battle of Fiisa. For three months Bulsa villages had to suffer from Babatu’s attacks. After a defeat or before Babatu had reached their villages, Bulsa men fled from other villages (e.g. Wiaga, Fumbisi and Kunkwa) to Sandema to join the Sandema army. Thus all Bulsa were united and ready to fight Babatu. People from Navrongo had at first fled to Kologo, but when they recognized that these people could not help them, they took refuge in Sandema. In the battle of Fiisa, Babatu’s army was beaten.

I received similar information when I visited Fiisa, and some people showed me parts of weapons that had been used in the battle there (see photo). In the 1960s people who visited the site near the earth shrine of Azagsuk were even shown two rifles used by Babatu’s soldiers.

Part of a Zabarima Dane Gun, shown to visitors in Fiisa

A more common theory seems to be that the big battle took place south of Sandema. The late Apagyie from Wiaga-Tankunsa told my assistant, Danlardy Leander, that armed warriors from Wiaga fled to Sandema when Babatu was approaching. With the help of other Bulsa and the

White Man, Babatu was beaten at a place near Akumcham. The statement that white people were involved in this battle is certainly wrong.

George Atemboa’s account (Howell 1998: 24) lends credence to a battle having taken place south of Sandema and states that Babatu camped at Wiaga. On his way to Sandema people of Kori blocked his army at the hill of Adakurik, not far from the battlefield.

Perrault could even collect some detailed data about the battle that, according to his information, took place between Sandema market and the (Old) Primary School. The following is a quote from his unpublished typescript (1954: 94-95):

The Bulsa “had learned that the Dane guns [the muzzle loaders of the Zabarima] were dangerous but that Babatu’s soldiers were powerless while they were reloading. The Builsas were lying on the ground and waited until the first shot had been fired. Then they got up, rushed the soldiers of Babatu and killed them with bows and arrows, spears and axes. Within two hours the Builsas were victorious and Babatu was retreating in disorder to Doninga. He was pursued there and had to cross the Sissili….”

How can we reconcile the two theories about the historical site of the battle of Sandema? When we consider that Babatu made several campaigns into Bulsaland, it cannot be ruled out that two battles near Sandema took place. Olivier, the Commissioner of the Navrongo District, got his knowledge from Babatu’s horse boy who had accompanied Babatu in his campaigns into Bulsaland and Navrongo. In Olivier’s unpublished typescript (1933) we find an important clue about the idea of two battles:

Babatu then made raids into the Navrongo District to Chiana and Nakon where he was driven away. He went back to Seti and recruited more men and came back on several occasions and for many years, invading Nakon, Chiana, Paga, Navoro [Navrongo] and then into Builsa country where he was again beaten at Sandema…

Olivier speaks about two defeats of Babatu, one near Chiana [Chana] and Nakon and the other at Sandema. It is possible that during the first-mentioned campaign a battle near Azagsuk, the Fiisa earth-shrine, took place since this tanggbain is only 2.5 kilometres away from Chiana. Over time the horse boy’s report of the successful fights against Babatu near Azagsuk melded perhaps with reports of Nakong and Chana fending off the Zabarima.

Furthermore, in other historical sources we find evidence for two victorious battles of Sandema. Lieutenant-Colonel Morris, after his campaign against Sandema in 1902, held a “large reception of all the chiefs of Tiana [Chana]”. They informed him “that the people of Sinlieh [Sandema] were most hostile, and owing to their having defeated Barbatu on two occasions, had a vast idea of their own power and importance” (Morris 1902, Diary).

We still have to posit the year when the battle (or battles) of Sandema took place. In all of our sources, it is clear that Babatu started the campaign against the Bulsa and Navrongo from Sati/Seti which had been the capital and residence of Babatu and his army since about 1890 or some years before (endnote 8). It also seems to be undisputed that the fight in Sandema took place before the battle of Kanjaga, for which we have an exact date, namely March 14, 1897. Holden (1965: 75) dated Babatu’s campaigns against the central Bulsa to 1890 or 1891 because in Wiase, Kunkwa and Fumbisi he received information that it took place about 5 years before the whites came to fight the Zabarima. Some Bulsa informants, however, report that Babatu started the battle at Kanjaga a short time after that of Sandema, which then might have taken place some time after 1891. Perrault (1954: 94) mentions the year 1896.

This means that the battle took place between 1890 and March 1897.

The Battle of Kanjaga

In contrast to the battle of Sandema, we possess a detailed description of the battle of Kanjaga published by Anne-Marie Duperray from French and English sources (1984: 100-101), and there is no doubt about the date of March 14, 1897.

Babatu had attacked Kanjaga, defeated its inhabitants and captured their chief, Amnu (endnote 9), who was spared by the Zabarima after his promise to collaborate with them. This collaboration may have consisted of feeding Babatu’s soldiers after they had set up camp near the village.

At this time Babatu had to confront another enemy who emerged from his own ranks. His name was either Ameria or Hameria. As a young boy, he had been captured by Zabarima in his home village of Santejan, west of Kanjaga and in the Sisala area. Although the historians are not sure whether he was a Bulsa or a Sisala, it is certain that he had close contacts to his Sisala and Bulsa relatives even after he had become one of Babatu’s high officers.

There were probably many reasons for his and other Grunchi officers’ mutiny. One was that Zabarima leaders started selling Grunchi women in the Zabarima camp as slaves (Holden 1965: 78) and that one Zabarima officer took away the Gonja wife from a Grunchi officer (Tamakloe 1931: 54). Furthermore, Grunchi towns “which had enjoyed Zabarima protections and exemption from tax now began to lose this exemption” (Holden 1965: 78), thus provoking the anger of Grunchi officers in Babatu’s camp. Amaria and his new army were quite successful in battles against Babatu, and he even adopted the title “King of the Grunchi”. Before the battle of Kanjaga, Amaria set up his camp near Bachonsa, only about 3.8 km from Babatu’s camp near Kanjaga.

About this time, the British had already gained a foothold in the extreme north of modern day Ghana. Ferguson, who had a Fanti mother and a British father, was serving the British and had concluded several treaties of protection with chiefs of the northern tribes. Before the battle of Kanjaga, the British were in an intricate situation. The two local commanders of the British troops (Lieutenant Henderson and Captain Stewart) in the north could not act without instructions from the Governor in Accra, and these instructions were sometimes confused because the recommended tactics were constantly changing. As the British were interested in making the land north of the Gold Coast Colony a British protectorate, they could not remain neutral and inactive. They had to choose their adversaries and allies among the following powers:

(1) The renegade Ameria and his troops. This was certainly their most desirable ally, but Ameria had already established a firm alliance with the French and rejected any concurrence with the British.

(2) Samori’s officers and their troops in the west of modern Ghana could not be considered as a viable choice of allies. They probably planned the conquest of the Dagomba kingdom, which would have meant that the British expansion north of their colony was blocked.

(3) The French had quite good relations with the British in Europe, which should not be given up. Although in 1904 they concluded a treaty (the Entente Cordiale), and in the First Word War they fought side by side against the Germans they were fierce rivals in the African colonies. The British knew that the battles in the Grunchi area would define the later boundary between the two European powers.

(4) Finally the British considered establishing an alliance with Babatu. They had always preferred to have treaties with powerful leaders who could keep the many small native chiefdoms under control.

In a meeting with Babatu in 1897, the British Lieutenant Henderson tried to test the possibilities of an alliance. In Duperray’s book (p. 98), part of the dialogue between these two persons has been published, and, if we may trust the testimonials, the following short dialogue was part of their discussion (translated from the French by F. Kröger):

Babatu: I want to go to Léo. Where are my captives?

Henderson: But which captives?

Babatu: Hamaria and the Grunchi [mutineers].

Henderson: Hamaria is not your captive, for he is dependent on the French. By the way, you are a bad man, because you destroy everything that you meet on your way.

Even if this talk is not authentic in all details, we can see the main interests of the two interlocutors. Babatu was chiefly concerned with getting rid of Ameria, while Henderson feared an increase of French influence in this region. A further obstacle to the politically reasonable alliance was Henderson’s moral aversion to the slave raider.

Without any results in their meeting, the British group continued their expedition back to Wa where Henderson was taken prisoner and his unarmed friend Ferguson was shot by some of Samori’s men.

Only one month after Henderson’s contacts with Ameria and Babatu, the French commander Chanoine, coming from Ouagadougou, met Ameria in Bachonsa and gave a French flag to the neighbouring village of Doninga. The village’s acceptance of the flag can be regarded as symbolic recognition of French protection. But Babatu, still residing in Kanjaga, raided Doninga and burnt the flag. On March 14, 1897, both Chanoine and Ameria attacked Babatu. According to the late Sandemnaab Azantilow, the battle was fought near a spot called Ayiba. Despite some stories told by present-day Bulsa, the British were not involved in this battle.

A.M. Duperray, in her book on the Gurunsi (Grunchi), gives a vivid description of this decisive battle (p. 101; translated from the French by F. Kröger):

[Babatu] is surrounded by his best lieutenants, Issaka and Aliou Gadiari, at the head of 400 men armed with rifles and more than 200 horsemen. Babatu is severely beaten. He leaves 300 prisoners and a great part of his troops in Hamaria’s hands.

After the battle, Babatu and the rest of his army fled to Yagaba. Here they met the British Captain Stewart who granted Babatu and his men protection. In Bulsa accounts I sometimes heard that Babatu raided Yagaba and was then beaten by the British. This does not agree with the written sources.

A few days after Babatu’s arrival, Stewart received instructions from Accra saying that Babatu was the best ally for Britain for two reasons. First, Babatu was hostile to Ameria who had concluded a treaty with the French. More significantly, however, Babatu was hostile to Samori, who was the real menace (Holden 1965: 83). A formal agreement was drawn up in March 1897, by which Babatu claimed Dagarti and part of the Grunchi tribes, among them the Bulsa. He promised to “live under the law”, which meant he would give up his raids and serve only the British king, fight Samori’s troops and offer 500 of his men for the Gold Coast Constabulary. Nonetheless, when Babatu was beyond the reach of the British, he and his men, “being desperately short of provisions” (Holden 1965: 84), raided the villages of Bulienga and Ducie (between Yagaba and Wa) on June 6th, 1897. After this the British planned to send Babatu to Kumasi to stand trial for brigandage and murder (ibid.). Therefore Babatu left the British and, after another defeat in the battle at Gambaga, went to Yendi, which at that time belonged to a neutral zone between the German and British spheres of interest (see map). Most of his soldiers entered the Gold Coast Constabulary. According to Tamakloe (1931: 55) Babatu built his own house and even practised agriculture in Yendi. Here the valiant commander, the winner of numerous battles, the terror of many villages, died from the bite of a poisonous spider, a few years after 1900. According to Holden (1965: 85) he died probably within two years after the convention of 1899. Ahmed Bako Alhassan (1991: 19) mentions 1909 as the year of his death.

The Northern Territories and Independence

Sergeant Major Solla and John Kanjaga. (Source: Rattray 1932, Fig. 89)

A few years after Babatu had been defeated completely, the whole of Northern Ghana, then called the “Northern Territories of the Gold Coast”, became part of the British Empire. Soon after a campaign by Lieutenant-Colonel Morris against the Bulsa in 1902, the Sandemnaab Ayieta and a delegation of Bulsa men went to Gambaga, where Bulsaland became part of the Northern Territories. The Sandemnaab Azantilow remembered that he was a very small boy during that event. He told me that the following men accompanied their chief: Azuboro from Abilyeri, Abeuk from Awusiyeri, Afande from Tankunsa, Akanyame from Kobdem, Anab from Longsa, Akung from Nyaansa and others. One of Ayieta’s younger sisters joined them as their cook (endnote 10).

During the First and Second World War, Bulsa fought in the British army. There is a photo in Rattray’s book (1932: 398) on the Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland showing Sergeant Major Solla and John Kanjaga, both awarded with many war decorations. John Kanjaga had fought in the bloody battle of Verdun in 1916 (see photo).

When the Gold Coast became independent in 1957, this event was much welcomed by the Bulsa. Their enthusiasm for the new Republic called Ghana can be seen from the fact that many Bulsa fathers in 1957 called their new born children Aghana, Aghanalie, Ghanatta and so on.

In the early 1970s, the Sandemnaab Azantilow together with the Bulsa Youth Association and the divisional chiefs discussed the idea of a big annual festival in Sandema. According to Mathias Apen (Buluk 2015: 109), Mr Henry Akanko, the Chairman of the Bulsa Youth Association, presented the idea to the Sandem-naab Azantilow in 1973, who approached the then District Chief Executive, Mr Kwesei Marfo, for assistance. The DCE “accepted his idea and decided to commit his time and some of the resources of the Local Council to its organization” (p. 110).

The first Feok Festival, which was held in 1974, was based on the following ideas:

1) Like the religious feok harvest sacrifices in the traditional compounds, it should be a thanksgiving feast for a good harvest. This might be the reason why it is always celebrated in December.

2) Moreover, it should recall the defeat of Babatu in the battle of Sandema, which, under the command of Sandema, was fought by warriors drawn from nearly every quarter of Bulsaland.

The Feok-Festival has helped unite all Bulsa in friendship and harmony.

Although, in some early reports, the Bulsa are described as fierce warriors who fought decisively against Babatu as well as against the advance of the British in 1902, Bulsaland, according to A.K. Awedoba (2009: 113-121) has been almost completely spared from inter- and intra-tribal conflicts in recent times.

Endnotes

Endnote 1: For the archives that I consulted, see below: References / Archives. In Tamale and Accra I was joined by Yaw Akumasi Williams, to who I am very grateful.

Endnote 2: According to the Ghanaian Archaeologist Jobila Zakari, the oldest date of the Kintampo complex is 400 BC and comes from Ntereso while the latest is 1700 AD (Begho, Brong Ahafo Region).

Endnote 3: Cf. Tamakloe 1931. Historians differ in their statements about the exact number of slaves to be paid. A number of 200 (Tamakloe 1931: 19) sounds reasonable to me.

Endnote 4: Regarding the Zabarima leaders we do not have undisputed dates about their times of leadership.

Endnote 5: According to Levtzion (1968: 153) the Zaberma adventures in ‘Grunchi’ land, independent of the Dagomba, started probably c. 1870. He believes that Tamakloe’s date (1931: 45) is too early.

Endnote 6: Holden (1965: 66, footnote 35): Tamakloe gives Alfa Gazare’s leadership as lasting 12 years… and the Yendi Zabarima say that this leadership lasted 7 years…

Endnote 7: A more detailed version about the Bulsa defence against slave raids was published in Kröger 2008.

Endnote 8: Cf. Holden 1965: 75. In a footnote Levtzion (1968: 154) mentions that [the German traveller] Krause, passing through Sati in February 1887, found the Zaberma [Zabarima] already there.

Endnote 9: I could not find anything about a Kanjaga chief called Amnu in the archives.

Endnote 10: She was the only person still alive in the early 1970s, but I failed to interview her.

REFERENCES

Abu, Malam, see Piɫaszewicz.

Alhassan, Ahmed Bako 1991. Babatu. Tamale (typescript).

Anquandah, James 1998. Koma – Bulsa. Its Art and Archaeology. Rome: Istituto italiano per l’Africa e l’oriente Roma.

Apen, Mathias 2015. The Feok Festival of the People of Buluk. In: Buluk 8: 107-112.

Archives:

Ghana National Archives, Accra (NAG), particularly the reference-groups ADM 56 and 63.

Regional Archives Tamale (RAT), particularly register 6.

Public Record Office (PRO), Kew (Greater London), particularly the reference-group CO 96.

Bodleian Library of Commonwealth and African Studies at Rhodes House, Oxford.

Atemboa, George 1998. The impact of the slave trade on the Builsa. In: Howell 1998: 23-30.

Awedoba, A.K. (Collaborating researchers: Edward Salifu Mahama, Sylvanus M.A. Kuuire and Felix Longi) 2009. An Ethnographic Study of Northern Ghanaian Conflicts: Towards a Sustainable Peace. Key aspects of past, present and impending conflicts in Northern Ghana and the mechanisms for their address. Legon, Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers.

Duperray, Anne-Marie 1984. Les Gourounsi de Haute-Volta. Conquête et colonisation 1896-1933. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden.

Fortes, Meyer 1949. The Web of Kinship among the Tallensi. London: Oxford University Press.

Holden, J.J. 1965. The Zabarima Conquest of North-West Ghana. Part I, Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana, vol. VIII: 60-86.

Howell, Allison (ed.) 1998. The Slave Trade and Reconciliation: A Northern Ghanaian Perspective. Accra: Bible Church of Africa and SIM Ghana.

Johnson, Marion 1970. The Cowrie Currencies of West Africa. Part I, Journal of African History XI: 17-49.

Kröger, Franz 1992: Buli-English Dictionary. With an Introduction into Buli Grammar and an Index English-Buli. Lit Verlag Münster und Hamburg (572 pp.).

Kröger, Franz 2001. Materielle Kultur und traditionelles Handwerk bei den Bulsa (Nordghana). Forschungen zu Sprachen und Kulturen Afrikas (Hg. R. Schott), 2 Bände, Lit-Verlag, Münster und Hamburg (1109 pp.).

Kröger, Franz 2008. Raids and Refuge: The Bulsa in Babatu’s Slave Wars. Research Review, N.S., vol. 24,2, Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana: 25-38.

Kröger, Franz 2013. Who was this Atuga? Facts and Theories on the Origin of the Bulsa. Buluk 7: 69-88.

Kröger, Franz (ed.) and Ghanatta Ayaric (co-editor): 1999-2018. Buluk. Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society, no 1-11, printed edition and website: https://www.buluk.de.

Levtzion, Nehemia 1968. Muslims and Chiefs in West Africa. A Study of Islam in the Middle Volta Basin in the Pre-Colonial Period. Oxford: At the Clarendon Press.

Morris, A. 1902. Diary of Expedition to the Tiansi country. Gambaga, April 26, 1902; Public Record Office, London, CO 879, 78, 05939, no. 25352 (Enclosure no. G/105/N.T./02).

Olivier / Ollivant, S.J. 1933. A Short History of the Buli, Nankani and Kassena speaking People in the Navrongo Area of the Mamprusi District, Navrongo? (typescript).

Ozanne, P.C. 1971. Ghana: In: P.L. Shinnie, The African Iron Age. Oxford: 36-65.

Perrault, Rev. Fr. 1954. History of the Tribes of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast. Navrongo: St. John Bosco’s Press (typescript).

Piɫaszewicz, Stanisɫaw (ed.) 1992. The Zabarma Conquest of North-West Ghana and

UpperVolta – A Hausa Narrative “Histories of Samory and Babatu and Others” by Mallam Abu. Warszawa: Polska Akademia Nauk.

Rattray, Robert S. 1932. The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland. London: Oxford University Press.

Schott, Rüdiger 1977. Sources for a History of the Bulsa in Northern Ghana. Paideuma 23: 141-168.

Shinnie, P.L. and F.J. Kense 1988. Archaeology of Gonja, Ghana. Excavations at Daboya. The University of Calgary Press.

Tamakloe, Emmanuel Forster 1931. A Brief History of the Dagbamba People. Government Printing Office Accra.

York, R.N. 1972. Cowries as Type-Fossils in Ghanaian Archaeology. West African Journal of Archaeology 2: 93-101.