SECONDARY SOURCES

(UNDER CONSTRUCTION)

CONTENTS

Abu Mallam: A Hausa Narrative “Histories of Samory and Babatu and Others” (1992)

Ahmed Bako Alhassan: Babatu in Dagbon (Tamale 1991?)

Akanko, Peter Paul: Oral traditions of Builsa. Origin and early History of the Atuga’s Clan in the Builsa State (1700-1900). Rosengården 1988

Akankyalabey, Pauline: A History of the Builsa People (1984).

Akankyalabey, Pauline: Geschichte der Bulsa (2005)

German (original) Edition; English Translation

Akankyalabey, Melanie (Ed., Sub Committee Chairperson)

[The Catholic Mission of Wiaga] Title Page missing, (2003)

Asianab, Francis Afoko (Private Notes): The Ayietas (1970)

Awedoba, Albert K.: The Chuchuliga Chieftaincy Affair (2009)

Bening, R.B. : The Regional Boundaries of Ghana 1874-1972 (1973)

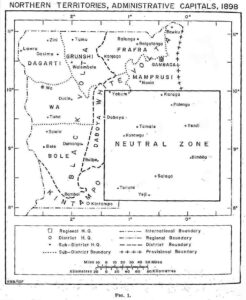

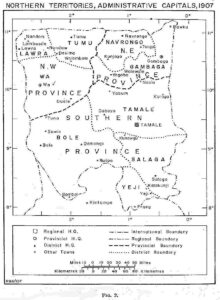

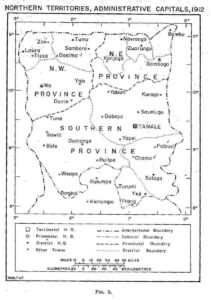

Bening, R.B. : Location of district adminstrative capitals in the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast (1897-1951) (1975)

Berinyuu, Abraham: History of the Presbyterian Church in Northern Ghana (1997)

Cardinall, A.W. The Natives of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast – their Customs, Religion and Folkore (1920).

Clarke, John: Specimens of African Dialects 1848-1849 (1972)

Davies, O. (compiler): Ghana Field Notes, Part 2: Northern Ghana, Legon 1970.

Delafosse, Maurice: Haut-Sénégal-Niger, Tome II, L’Histoire, Paris 1972.

Der, Benedict G.: Christian Missions and the Expansion of Western Education in Northern Ghana, 1906-1975 (2001)

Duperray, Anne-Marie: Les Gourounsi de Haute Volta, Wiesbaden 1984

French and English Translation

Gariba, Joshua: Weaving the Fabric of Life: An Anthropological Presentation of Traditional Dwelling Culture among the Bulsa of North Eastern Ghana

Holden, J.: The Zabarima Conquest of North-west Ghana Part I (1965)

Howell, Allison M: The Religious Itinary of a Ghanaian People. The Kasena and the Christian Gospel. Frankfurt 1997.

Koelle, Sigismund Wilhelm, Polyglotta Africana, first edition London 1854, Reprint Graz, Austria 1963

Köhler, Oswin: Die Territorialgeschichte des östlichen Nigerbogens (1958)

Kröger, Franz: Ancestor Worship among the Bulsa of Northern Ghana (1982).

Kröger, Franz: Die Erforschung der Bulsa-Kultur (2005)

German (original) Edition and English translation

Kröger, Franz:

The following articles by F. Kröger were published in the internet journal Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and History. As they can easily be downloaded from the website https://buluk.de/new it can be dispensed with the whole or part of the text reproduction.

— The First Europeans in the Bulsa Area. Buluk 3 (2003): 29-32.

— The First Map of Bulsa Villages. Buluk 4 (2005): p. 23.

— Christian Churches and Communities in the Bulsa District. Buluk 4 (2005): 43-57.

— Islam in Northern Ghana and among the Bulsa. Buluk 4 (2005): 58-61.

— Extracts from Bulsa History: Sandema Chiefs before Azantilow. Buluk 6 (2012): 47-50.

— Kunkwa, Kategra and Jadema: The Sandemnaab’s Lawsuit. Buluk 6 (2012): 51-58.

— Swearing in of the Bulsa Chiefs in 1973. Buluk 6 (20112): 43-44.

— Bulsa Chiefs and Chiefdoms. Buluk 6 (2012): 64-78.

— Who was this Atuga? Facts and Theories on the Origin of the Bulsa. Buluk 7 (2013): 69-88.

— Colonial Officers and Bulsa Chiefs (with special consideration of elections). Buluk 7 (2013): 89-100.

— Two Early Plays on Bulsa History. Buluk 7 (2013): 106-108.

— Means of Transport in History and Today (Northern Territories, Ghana). Buluk 7 (2013): 109-113.

— Extracts from the Diary of Sir Shenton Thomas, Governor of the Gold Coast – Meyer Fortes in Bulsaland (1934). Buluk 8 (2015): 90-91.

— History of Bulsa Journals. Buluk 8 (2015): 104-106.

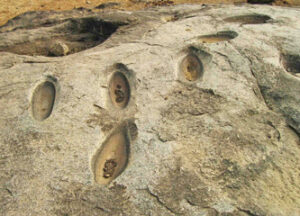

— Old Oval Grooves and Cylindrical hollows in granite outcrops. Buluk 9 (2016): 69.

Ollivant (D.C.): A short history of the Buli, Nankani and Kassene speaking people in the Navrongo area of the Mamprusi District (1933)

Packham, E.S.: Notes on the development of the Native Authorities in the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast (1950)

Parsons, D. St. John: Legends of Northern Ghana. London 1958

Perrault, P., Rev. Fr., W.F.: History of the tribes of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast. Navrongo (1954)

Rattray, Capt. Robert S.: The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland, reprint 1969

Rodrigues, Raymundo Nina: Os africanos no Brasil (2010)

Schott, Rüdiger: Sources for a History of the Bulsa in Northern Ghana (1977)

Williamson, Thora: Chronicles of Political Officers in West Africa, 1900-1919 (2000)

Zwernemann, Jürgen: Ein “Gurunsi”-Vokabular aus Bahia – Ein Beitrag zur Afro-Amerikanistsik (1968) – German and English translation

Abu Mallam: A Hausa Narrative “Histories of Samory and Babatu and Others”

Translated by Pilaszewicz, Stanislaw: The Zabarma Conquest of North-West Ghana and Upper Volta.

Warszawa 1992

[F.K.: This publication contains most important primary sources on Babatu and Samori]

Preface

p. 8

The manuscript under discussion was written in 1914 by a certain Mallam Abu and bears an English title.

Introduction (by Pilaszewicz):

p. 11

We have not information concerning the author of the manuscript and his literary activities. One has to adept his won statement that he took part in the Zabarma raids. It is quite possible that he might have accompanied the Zabarmas in their expeditions under Gazari and Babatu’s leadership…

p. 19

The name Zabarma is a Hausa word for the Jerma people, related to Songhai. In literature concerning Africa there are many variant forms of their name, for example, Zarma, Dyerma, Dyabarma, Zabarima, Zamberba, Djermabe etc.

Chapter one: Babatu

p.72

Fn 1: Babatu d’an Isa (known also as Mahama d’an Isa) came from Indunga… He succeeded Alfa Gazari and in the early 1880s became the unchallenged leader…

p. 84

Here is a story of Emir Babatu d’an Isa,

…The ruler of Paga-Buru boasted as well. Thc ruler of Paga-Buru sent to the ruler of Chuchiliga (footnote 75). He also, he made preparations for war and set about. They all assembled together with their troops: the ruler of Navrongo – the town was called Navrongo, the ruler of Chuchiliga – the town was called Chuchiliga, and the ruler of Paga-Buru – the town was called Paga-Buru. They all assembled together with their troops and came to Emir Babatu, [to] the war commander, thc ruler of Gurunsi. They collided with Emir Babatu on the bank of this stream. Emir d’an Isa beat them on that day and drove there away. They were running away and thc Zabarma people were following and killing them. In such a way Emir Babatu conquered the Buru country, he caught their chiefs and killed them. This story is also ended.

(footnote ) 75 In ms. Zuzulo. Another spelling, Juljulo, is also possible. This may be identified with Chuchiliga, a locality in the area under consideration…

p. 88

Here is a story of Emir Babatu

…He stayed in Korogo. [Then] he started on a journey to Sati. He reached a certain town. A great soldier of Gazari, whose name was Amariya (footnoe 98) rose in revolt…

(footnote ) 98 Amariya or Hamaria served as a war chief under Gazari. According to Holden (1965:78) he was born in Santijan near Kanjaga, on the Sisala-Builsa boundary. At the age of seven he was taken by Alfa Hano after whose death he served Alfa Gazari. At the time of revolt he was in charge of Babatu’s guns and powder, and held a high office in Sati. He is said to have heard judicial cases in Sati just like the other Zabarma leaders. He is regarded as having been literate and Muslim.

p. 92

Here is a story of Babatu

He set out from Sankana towards the Kanjaga country. He went and reached a certain town. The town was called Nangruma (footnote 119) [Its] people brought many presents and he accepted their presents. He stayed [there], he had a rest and [then] set forth. This story is also ended.

Here is a story of Babatu

He set out from Nangruma and went to Kanjaga, He reached Kanjaga and stayed in Kanjaga for one month. One day he heard the news as if Amariya and Balugu were coming. Babatu said that it was a lie. [Then] one man came [there] and said: “Babatu, Amariya drew very near [to this place]”. Babatu called his people and said: “Did you hear [it]?” They said that they heard. Another man came and said: “Babatu, make thorough preparations. There are some Europeans among them, I saw [them], it is not a [mere] rumour.” Babatu became silent. The second day, on Sunday in the morning, [when] Babatu had a rest, he heard gun-play. It was said that Amariya came with the

(footnote) 119 In ms. Naguruma – a town in northern Ghana (Ghana, Navrongo sheet).

p.93

Europeans of French origin (footnote 120) Babatu set forth arid collided with Amariya and his people, with him and the Europeans of French origin. Babatu, ruler of the Gurunsi.

The Europeans of French origin gathered many Gurunsi people, more than ten thousand people. Babatu killed all of them. As for Amariya, the Frenchmen did not see him that day. He ran away in panic, Balugu ran away in panic and Napere ran away in panic. Babatu drove away many Gurunsi people. He did not collide with the Europeans of French origin. But Babatu split them and drove away all the Gurunsi people. Emir Babatu, war commander, The Europeans of French origin and Babatu, they opposed each other very fiercely. A European of French origin felt indignant with Babatu. He fired a shot at Babatu but he missed. He (Babatu) was more valuable than ten [of them]. Emir Babatu was defeating [them], and the Zabarma people were shouting at them, The Europeans of French origin were worried and they did not rest in Kanjaga (footnote 121). [They stayed] in a certain town. The town was called Fumbisi. Babatu drove them away that day, but Ali Gazari’s son lost his [life] that day, That day Babatu stayed in Kanjaga. When it dawned, Babatu went to Yagaba (footnote 122). The town was called Yagaba. He stayed [there]. This story is also ended.

Here is a story of Babatu

He came upon the Europeans of English origin (footnote 123). They were many in Yagaba. They exchanged greetings with Babatu. As for Babatu, they summoned Babatu and said: “Babatu, stop fighting.” Babatu said that he agreed and that he would appease. [Then] a European of French origin came to Yagaba together with Amariya. The European of French origin and the European of English origin came together and held a council (footnote 124). The European of French origin returned. Babatu and the Europeans of English origin, they set out from Yagaba and went to a eertain town. The town was called Yabaum (footnote 125). They (the Europeans) parted from Babatu. Babatu started on a journey to a certain town. The town was called Bantala (footnote 126).

(footnote) 120 The French columns headed by captain Voulet and his aide-de-camp Chaneine entered Wahiguya by August 17th and Wagadugu, capital of the Mossis by September 1st, 1896. On September 19th Voulet-Chanoine signed a treaty with Amariya whieh put the Gurunsis under French protectorate. Captain Voulet moved by damages caused by the Zabarma troops promised to help his new “subjects”.

Cf. Hébert (11: 17ff.) and Holden (1966:80-82).

(footnote) 121 European writers (Hébert 1961:17ff., Holden 1966:83) are unanirnous when stating that Babatu was defeated in Kanjaga. Also according to McWilliam (1960:40) it was Amariya who won the victory over Babatu.

(footnote) 122 In ms. Yagaba, a town in northernGhana…

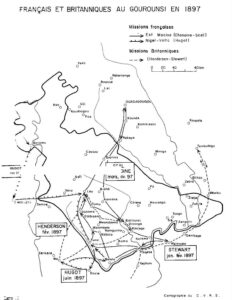

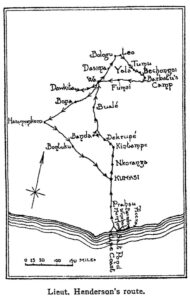

(footnote) 123 In 1896, havubg subdued the Ashantis and placed them under their protectorate, the British sent two expeditions to the north of the Gold Coast. One of them under lieutenant Henderson’s command (who was accompanied by G.F. Ferguson) in November, 1896 left Kumasi for Wa. The other, under captain Stewart’s command, went to Wagadugu. It was captain D. Stewart who met Babatu in Yagaba.

(footnote) 124 Probably the meeting of catpain Stewart with lieeutenant Scul is meant here. The latter one demanded extradition of Babatu, but captain Stewart refused to do it.

(footnote) 125 In Yagu – a town in northern Ghana, south of Daboya…

(footnote) 126 In Balali – a town in northern Ghana, on the way from Yabum to Ducie…

p. 98

Here is another story

They disputed about a certain town. The town was called Sinyensi (footnote 148) Umaru, son of Gazari said that Sinyensi belonged to him. Ali Muri claimed that Sinyensi was his. Emir Babatu settled the dispute. “Sinyensi belongs to Umaru, son of Gazari”. This story is also ended.

(footnote) 148 In ms. Sinisi – a town in north-west Ghana (Ghana, Wa sheet).

Ahmed Bako Alhassan: Babatu in Dagbon (Tamale 1991?)

[Note (F.K.): Alhassan, as he admits in his preface, adopted a very great deal of his text from Tamakloe (1931). He does not mention the Bulsa (Kanjagas) or any raids on Bulsa villages]

Preface (p. 1): The coming into being of this booklet – “BABATU IN DAGBON” has been made possible through the efforts of Alhaji Mahamadu Maida of Tamale. who is a grandson of Babatu, one of the slave raiders West Africa has ever known.

It was on the death of Hajia Rukaya Babatu the last living child of Babatu, and mother of Alhaji Maid on Friday, 22nd February 1991 that I suggested the compilation of this literature to posterity.

p. 18

Advantages that were had as a result of the presence of the Zabrama in Dagbon were many. Before their arrival, Dagbon know no horsemanship, not mentions weapons for fighting…

Again the arts of black-smithing, commerce, weaving and leathery were the produce of and skills of the Zabrama brought to Dagbon. Aside these the Islamic faith was propagated and taught in Dagbon, hence present Islam. [F.K.: These statement must be doubted]

Akanko, Peter Paul: Oral traditions of Builsa. Origin and early History of the Atuga’s Clan in the Builsa State (1700-1900).

Rosengården 1988

[Note (F.K.): Throughout Akanko’s text many references to Bulsa history can be found. In the following excerpt they have been neglected in favour of his table of contents and the unabridged appendices, containing his primary sources]

Contents (p. iii)

Acknowledgement V

Preface VII

Maps

1. Ghana, showing position of the Builsa State VIII

2. Northern Ghana, Builsa State

with towns and other places X

Chapters

I Early History and Growth of the Builsa State 1

II Origin of the Name Builsa 7

III The Origin and Growth of Atuga’s Clan in Builsa 13

IV The Political System in the State and why Atuga’s

Clan has the Paramountcy of the Ruling Power in Builsa 15

V Early Occupational Activities of the People 31

Appendix

1 References to Peoplc from whom I Collected oral Traditions

2 Questionnaire 47

3 Bibliographyp. 41

p. 41

Appendix 1

References to People from whom Local Oral Traditions Are Collected

*1 This oral information is collected from Mr. Leander Amoak from Sinyansa-Badomisa, one of the early settled sections of Wiaga. Her is one of the very first few educated men in the Builsa state and certainly one of the oldest teachers in Builsa. He is between 60 and 65ycars, and is now enjoying his retirement bonus at home.

According to him, the Builsa state is composed of different tribesmen with different customs, These different groups of people trace their origins to different countries outside the Builsa statc. These different groups of people included the descendants of Atuga and some southern villages which trace their origin and ancestory to the Mamprusi state, part of Kanjarga and Vare which trace their origin and ancestory to the Moshie of MOssi land and Gbedema, Doning and Chuchuliga which trace their origin and ancestory to Gurenshiland or Yiulug.

This information has been cross-checked with other elderly people:

Adum Asaghc, Akaduk-Anasarek, Akardem and Apagyie from Wiaga, Mr. Joseph Atiim from Kanjarga, Mr. Gabriel Abang from Gbedema, Mr. Clement Atiirembey from Chuchuliga and Mr. Christopher Abuuk from Kadem. All these people seem to identify themselves with Mr. Amoak’s view.

*2 This oral information has been collected from Adum Asaghe of Sinyansa. His age is between 70 and 75. Most people in Wiaga acknowledge him as a knowledgeable oldman who is vested in the traditions of the Builsa state.

In his view, most of the Builsas are descendants of the Mamprusi and Dagombas. The capital town of the Mamprusi state where their chief resided was and is still called Nalerigu. According to his interpretation. Nalerigu means “the chief is coming”. In his opinion Anaaniteng was the owner of the whole Mamprusi and Builsa lands.

This Annanitang gave birth to the following sons: Atandaga, Akomoa. Alaaba, Kovareng, Achoeba, Awabuluk, Wanwaring, Aboruk, Akandenoa and Achianbiik.

According to him, Achoeba is said to be the ancestor of Niaga und Nankani peoplc. Awabaluuk the ancestor of Builsa. Achianbiik, the ancestor of Chiana and Aboruk and Awanwaring,

p. 42

the ancestors of Chuchuliga people. But the name Chuchuliga is derived from a person called Achuchulo who came from Chibele- Pogu in Upper Volta later on, and by virtue of his superiority, lorded it over the descendants of Aboruk and Awanwaring and so

gave his name to the place known in the Builsa . state today as Chuchuliga. I cross-checked this ‘Achuchulo’ story as told by Adum Asaghe with Mr. Clement Atiirembey, a Chuchuliga born and he too shares the sane views.

According to Asaghc, Bachonsa, Kunkuck, Uwasi, Kategra, Fumbisi, Weisi and part of Kanjarga are all descendants oi Anaaniteng

too. According to my several cross-checked interviews, his view seems to be widely held by most Builsas.

*3 This information is collected from the old Adum Asaghe again. According to him, before Atuga came to Builsa, the descendants of Awabuluk were already living in the place, The first group of Awabuluk’s descendants was called Builiba after Awabuluk and the name Builsa might have certainly been derived from the name Builiba. the Builiba were believed to have settled between Kadema and Zamsa. they regarded Atuga and his men as brothers and so readily received then and allowed them to settle at any place in the Builsa state. He holds the view that the reason for the immigration of Atuga’s father from Mamprusi was over thc quest ion of the traditional circumcision among the Mamprusis. He also holds the view that Atuga settled at the place called Atuga- Guuk between Wiaga and Sandema. He has a lot of sympathisers on the reason for Immigration and settlement place of Atuga bur then his opponents arc also quite a good number.

*4 This information is collected from Lawrence Amoak from Kpandema, a section of Wiaga. His age is between 60 and 64. He is one of the few early Christians and about one of the oldest Catechists of the Roman Catholic White Missionaries in Builsa. He has certainly travelled widely with thc early Missionaries to the various villages in the Builsa state, A good number of people believe that he has got a commanding knowledge about thc traditions of the state.

According to him, when the Builsa became fully settled, the place was visited by thc. Mamprusi Chief of Nalerigu. Since thc majority of Builsas believed to have originated from the Mamprusi state, it therefore followed that the Mamprusi chief regarded them as his people.

The Builsas met him at the Yagaba Mighty dam. According to him, the Mamprusi chief was wondering whether there were rivers in the area, and so inquired from the people to know where they

p. 43

got their water from. The people replied that they got their water from “builisa” meaning wells. When the Mamprusi chief hear this, he said, “then you were better called “builsa”, wells, After this meeting the inhabitants of the area were then referred to as ‘Builsa’ up to this day.

This Amoak is also one of the Protagonists who holds the view that Atuga settled at Kadema-Badiok and not at the place called Atuga-Guuk between Wiaga and Sandema, as other people have it. He also holds the view that Agyabkai left the Mamprusi state because his brothers wanted to kill him.

This man also holds the view that Atuga first settled at Kadema Bagdiok, then he next moved to the place called Atuga- Guuk and finally returned to Bagdiok because he had no prosperity at that place now called Atuga-Guuk.

*5 This information is collected from Mr. Leander Amoak, whom I have already referred to in Appendix 1 (*1) on page 5.

According to him, the original people of the Builsa state first settled by a magic pond or well – “builik’ with its water springing from under the ground like that of a fountain. While they were always waiting to draw the water from this pond for drinking, they often hear thc continuous springing sound of the water. from the pond making Buil buil! buil! and then it changed to buil-i-sa! buil-i-sa! buil-i-sa! Soon the people got used to the sound and began imitating it “bul! buil-i-sa! This then became a household word. As the settlement became expansive, the people found that there were several of those kind of wells or ponds. So thc area was called Builsa after the “buil” buil-i-sa!” sounds from the numerous ponds which were increasing in great numbers as thc settlement expanded. this name has remained as the name of the area till this day.

*6 This information is collected from Aboora and Akardem. These two men both share the same view on the immigration of

Atuga’s father from the Mamprusi state.

Aboora is from Longsa, a section of Wiaga, He is between 55 and 60 years old. His father has been one of the early traders in the state and had travelled far and wide outside the state. He might have come across a good number of people from other states and so might have heard a lot of stories about them. According to Abooru himself his father died when he (Aboora) was quite of age and so he has heard a lot of stories from his father about the state. Aboora is well respected for his undisputable knowledge about the traditions of the state.

Akardem is an old man of Central Wiaga. This section is

p. 44

called Yisobsah-Dogblinsa, The people of this section are regarded as the rightful owners of the land of Wiaga. Akardem’s father was

one of the early lords or “earth priests” of Wiaga. Akardem is therefore regarded in a large circle of people as a person vested in the traditions of the state. He is between 70 and 76 years of age.

According to these two men, Atuga was the son of Agyabkai and Apoomsebfanyese. Agyabkai was the eldest son of the Mamprusi chief at Nalerigu. In their opinion Agyabkai wanted to overthrow his father to become the chief instead. But his father noticed his intention in time and so wanted to kill him. However, Agyabkai also realised that his father was after his block and was therefore always almost at large. When his father failed to trap him, he denounced him as a son. Agyabkai and his family together with some followers therefore left the Mamprusi state for safety. From the Mamprusi state they moved along the south-eastern boundary through Waung and Kpesinkpe and then went to settle at Salaga.

But Salaga as a centre of trade, slave market and generally a hot place to live, they next moved from there and came to settle at Walewale. Here, Agyabkai got married to Apoomsebfenyese and gave birth to Atuga, After a very long period of stay at Walewale, Agyabkai died and left Atuga and his mother and followers there. By then Atuga was quite of age and so he assumed leadership of the group. Atuga and his followers were deprived of enough land to do farming. so they moved from Walewale, passing through the Nankani-Gurensi land and Niaga and finally came to settle at the place called today as Kadema-Badiok.

There, Atuga and his men met the Builiba who readily received them as their brothers and gave them land and they settled peacefully among them. After some time Atuga got married to Amwanyasalie from Tankansa and gave birth to four sons, Akaresa, Awiak, Assandem and Asenee, who became the founders of the present Kadema, Wiaga, Sandema and Siniensi. these four villages form the Atuga clan group in the Builsa state.

*7 This information is collected from Akaduk-Anasarek and cross-checked from Akardem, Aboora, Adum Asaghe and Mr. Leander Amoak whom I have already referred to more than once.

Akarduk-Anasarek is an elderly man from Wiaga-Guuta. He is aged between 63 and 68. His father was one of the early traders in the state. When Asarek was of age, he had the chance of travelling with him from place to place. People hold him as one of the knowledgeable persons in the traditions of the state.

According to Akardem, Aboora, Adum-Asaghe, Mr. Leander Amoak and Akarduk-Anasarek, who all hold the same view on the name of Atuga’s four sons, when Atuga got married and had his four sons, he could not name them from the on set. But then one

p. 45

day he went hunting and happened to kill a cow. When the woe [cow?] was brought home and skinned, he asked the people to cut it into reasonable chunks. When this was done, he took the chance to test the intelligence of his sons by asking them to choose the chunk of the cow they liked best in turns. The first son chose the bony legs, shins, known as “Karesa”. When they asked him why he chose the ‘karesa’ he said they were strong and the cow used them in walking.

The second son chose a whole thigh, known as “Wiek” and cut it into pieces. When he was asked the reason for his choice and process, he said he wanted to preserve it for future use because it was too much for a day’s meal; Moreover, it was not easy to come by meat everyday. The process of preservation is known as “Wiarka”. This showed sense of wisdom in him and he was referred to as the wisest of all the four sons, after they had all made their choice.

The third born chose the bladder known as “Sinsamluik”. His reason was that there was water in it. The fourth and last born chose the chest called “Sunum” and cut it into. pieces for roasting on fire which he had prepared for eating on the spot. The process of roasting and eating of the pieces of meat is known as “Seneeka” or “Seliensika”. His reason was that the meat was meant to be used as food and so must be eaten. Through this he was able to get names for all his four sons.

The first son chose bonny legs ” karek-karesa – so he was called Akardem. The second son chose the thigh and cut it into pieces for preservation – thigh- Wiek, perservation- Wiarka, so he was called Awiark or Awiak, The third son chose bladder – Sinsamluik-

Asinsam and so he was called Asamdam – short form of Asinsam. Lastly the fourth son chose the chest and cut it into pieces to toast and eat on the spot – seneeka – or sellensika- selsensi-sense and so he was also called Asinieng, These his four sons – Akardem, Awiak, Asamdem and Asinieng grew up to give their names to the present day Kadema, Wiaga, Sandema and Siniensi, the four Atuga clan villages in the Builsa state.

*8 This information is collected from Mr. Joseph Atiim from Kanjarga. He has been one of the first persons to attend the first Government Primary School in the state and later at the Tamale Boys’ Senior School for the Northern Territories. This is now the Tamale Secondary School, former Government Secondary School. He has therefore, a mature mind about the traditions of the state by virtue of his early experience as an educated person. He is between 40 and 44. He is a senior teacher and the head teacher of the Builsa Middle Boarding and Continuation School. His information has been cross-checked with Mr. Leander Amoak, Adum Asaghe, Akardem Aboora and several others from the four villages of Atuga

p. 46

and all seem to share his view on chiefship in the state.

According to him and his protagonists, the idea of chiefship appears to be a borrowed term from the Mamprusis who called

their chief “Na”. The term might have been ancestory inheritance because most Builsas traced their origin to the Mamprusis. So a person who seemed to exert some ruling power was called “Nab” or chief. It was generally the “earth priests” teng-nyam who exerted ruling powers over the people on ancestory lines as if he had his powers from the Mamprusi state – their ancestory state. but these sort of rulers were regarded as rulers on religious terms.

Later on same plutocrats (Dobreba) rose up and by virture of their wealth seised power to rule as “nalema” or chiefs. Thus the saying “nanta nyono le nab”, meaning a wealthy man is obviously a chief, which has remained with the Builsas up to this day. These plutocrats were often approved by the people as leaders on the basis of the sort of leadership they gave. However, there was no guarantee that one plutocrat or a group of plutocrats could rule as “nalema” forever.

The rule by the “earth priests” with delegated ancestory powers from the Mamprusi state was known as “naik naam”, that is to say ancestory chiefship, this was because these ‘earth priests” claimed that they had their divine powers to rule from the people’s ancestory land.

According to Akardem, the people who were ruling with ancestory powers in some of the villages before the coming of the Europeans to the Builsa state were: Akomwab at Kadema, Awuumi of Yimonsa at Wiaga, Anamkum at Sandema, Abaagyie at Siniensi, Anapagye-Achoata-Atibilat Kanjarga and Anyiamjutee at Fumbisi,

But with the arrival of the whitemen, there was a change from traditional chiefship to Europeanised chiefship because the traditional leaders were not ready to co-operate with the whites, they were never on the spot to meet these Europeans when they arrived. They could not provide carriers to carry their luggage and so on. While there was this sort of board pulling relations between

the traditional leaders and their white visitors, there were people in the various villages of the state who were often ready to meet the whitemen to give them the needed help. The whitemen could not fail to notice these men with leadership qualities and co-operative spirit. So when the whitemen came to have full control in the state they did not hesitate to do away with these uncompromising traditional leaders.

This interruptions by the Europeans then gave birth to modem

chiefship in the state. People who became the first Europeanised chiefs in some of the villages in the state were: Atigbiurou at Kadema, Ateng at Wiaga, Anamkum still remained chief of Sandema Abadiin at Sinienai, Ankangnab at Kanjarga and Ayaagyig at Fumbisi. With these changes in leaders, the chiefs then ruled on modern lines. However, there was still that feeling of ancestory powers, so although the chiefs were chosen by Europeans, they

p. 46

still had to go to Nalerigu and Kpensinkpe for confirmation by the Mamprusi chief. This was necessary because the people wished to rule with the consent of their ancestors.

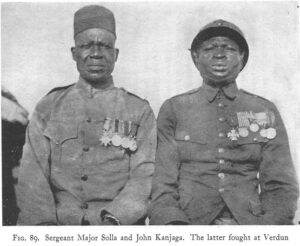

*9 Sergeant Akanluba Adamu is a person who has seen services in both the gold Coast Regiment as a soldier and later on as a Policeman. As a soldier he saw action in both the First and Second World Wars – 1914-1918 and 1939-1945. According to him most Builsa soldiers saw action in these two wars. According to him, the Builsas (then popularly known as Kanjargas) were described as ‘the men who never fear death”. As regard the recruitment of soldiers for the Second World War, he quoted the paramount chief Mr. Azantilow as saying “if thousand Builsas are killed in this war I will give another thousand”. This was after a British Officer came to the state and recommended the bravery of the Builsas to him and requested that he should get ready for further supply of soldiers for the Gold Coast Regiment.

Akankyalabey, Pauline: A History of the Builsa People

(Legon 1984)

Dissertation… for the Award of the B.A. Degree

(Note F.K.: Since the whole thesis is concerned with Bulsa history, we have not printed all significant passages, but have enlisted something like a summary or index. Her main results can also be found in Akankyalabey 2005, following the part)

Introduction: vi: …the Builsas never developed the art of the drummer… [to preserve] their history…

Chapter one: The origins and migrations of the Builsa People (1-23)

p. 1-3: derivation of the name “Builsa” (section of Kadema…; bulik, well);

p. 4: the name “Kanjargas”

p. 5: a “hotch-potch” people (Rattray)

p. 6: Ananiteng (in Zamsa) as the founding ancestor of the indigenous Builsa…

p. 7: indigenous people: Kadema: Builiba, Tengdagrisa, Achianbisa, Taaba and Kovarensa,

Wiaga: Kperengse, Komdem, Chamdem, Tankansa (founder Atankang); Sandema: Badiinsa, Kanaansa, Bambalsa; people of Vare (extinct). …all claim that their ancestors came from the sky

p. 8ff: immigrants: four main immigrant groups between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries: Kasem-Isala speaking group from the north, a Sisala group from the west, a Mole-speaking group from the Tallensi area and a Mamprulli group from the south and south-west

p. 9: blacksmith sections in: Kanjarga, Chuchuliga, Fumbisi, Sandema, Wiaga; all taboo the cricket pang.

p. 10: Sisala immigrants… came mainly from Santejan (or Kong). Some settled at… Kanjarga, others at Dongning and Sandema where they founded… Kandem

Dogninga: founder Adogning, a hunter who probably migrated from the Nankanni area. He first settled in Kandiga… rode on a bushcow to the present Dogninga; killed people and settled there with his family

p. 11: Other versions of the origin of Dogninga say that its founder come from Wiaga or Kadem, while other claim that Dogninga was an offshoot of Kanjarga.

immigrants of the area of Tongo; … the descendants … are those of Agoak or Along in Wiaga and especially the people of Gbedema, where Atong founded an off-shoot of… the external bogar near Tengsugu

p. 12: …two groups of immigrants… from the east or south-east… related to the Mamprusi…

One of them have Atuga as their founding father. He was a Mamprusi prince who left Nalerigu and settled at Atuga-guuk (near Sandema Junior Boarding School). His sons founded the four major villages of Sandema, Wiaga, Kadema and Siniensi.

The other group which also migrated from Mamprusi land was led by Afia and they founded Fumbisi from where later the people of Kategra branched off. In addition, a man called Akunjong is said to have left Nalerigu, settled at Kpasinkpe and he or his son later founded Kanjarga. There are, however, conflicting traditions relative to the foundation of Kanjarga (see Rattray, p. 400).

p. 14: …the story of the lone hunter who founded the settlement of Dogninga…

…when the immigrants came to the Builsas, they were welcomed by the indigenous people who gave them land to settle… Soon the immigrants adopted the Builsa language and (p.15) the Builsa way of life.

(p. 15)… some of the pre-existing people migrated to Kologu in the east, Naga in the west, Nakong and Katiuk in the north and others to Sisala-land.

THE POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC ORGANISATION

p. 15-23 (no detailed excerpts here): … the position of the teng-nyono; the wealthy men (dobroba); clans; sections; the compound; marriage; system of inheritance patrilineal; agriculture; blacksmiths

CHAPTER TWO: TOWARDS THE FORMATION OF A BUILSA STATE (1700-1897)

p. 24: …Atuga’s father was an elder son of the Nayiri of Mamprusi. He was called Agurima but other traditions refer to him as Agyabkai or Wurama (cf. Cardinall p. 11).

p. 25:

(1) …Agurima was undermining his father with an aim of deposing him and becoming chief of Mamprusi.. he seduced the most beloved wife of his father

(2)…Agurima moved away from the Mamprusi state because he disagreed with his father about the question of circumcision… Agurima refused to have his children circumcised…

p. 26: (3) — dispute among Agurima’ brothers..[who] planned to kill him

(4) According to G.A. Achaab, “the migration occurred during a war between Mamprugu and Dagbon. While fighting, the Nayiri decided to build a wall of protection around Nalerigu. The wall was to be built with a mixture of earth, shea-butter and honey to make it stronger. Atuga, a prince, set out to find the honey. he, however, got lost in the bush and in his wandering came to Kadema where he settled with one Abuluk ( Inf. G.A. Achaab).

(5) Atuga was a good and kind man… His brothers were envious of this… They seized Atuga ‘s pregnant wife and ripped her belly open. This resulted in a fight (p. 27) between atuga and his brothers… Atuga mounted a horse which took him to the Gambaga scarp… [then] they moved to Salaga… From Salaga they moved to Walewale where Agurima died… then Atuga assumed leadership and moved to Kpesinkpe (Inf. Sandemnab to Schott, p. 9).

p. 28:

Views: Atuga settled in “Bag diak (Kadema; Inf. Lewis Awiadem and Awuchansa) or at Atuga Guuk. His grave at Atuga Guuk marked by a tree called “Atuga-pusik.

p. 29: The Growth and Expansion of Atuga’s clan

Atuga married a woman from Tankangsa called Amwanyagsalie. …other versions: … married a daughter of Abuluk. Anecdote about animal meat….

p. 31: Political, Social and Economic Change (1700-1897)

earthpriests.. chiefs with limited power…

p. 33: traditional chiefs of Wiaga: Awuumi and Anankansa of Yimonsa; Yimonsa was founded by Ayimoning, Awiak’s son.

p. 34: Akomwob, a descendant of Akaa became chief of Kadema; Abaagyi, a descendant of Asenee or Asenieng became chief of Siniensi. Sandema: Ananguna and Anankum.

Kanjaga: Atibil; Fumbisi: Anyiamjutee, Gbedema: Atong. But since the ancestors Atibil and Atong did not come from Mamprusi, they did not go there for the “naam”. Atong is said to have gone to Tongo while Atibil might have gone to Sisala land for his “naam” (Lewis Awiadem).

colonial administration brought the Builsas under Mamprugu in 1912.

p. 37: The people of Bachonsa assert that their grandfathers came from Wiaga under Afeok who met some Kasena on the land. …the people of Fumbisi drove the Wiasi people away to where they are now,

p. 38: economy, local crafts…

p. 40: The Zabarima Invasion of Builsa (after Holden…)

p. 44: …the raids of Babatu led to the union of the Builsas. …decision to unite under Sandema have Sandem as the capital.

p. 45:

CHAPTER THREE: The contact with Europe (1897-1951)

p. 46: Delafosse: “Le 14 Mars 1897, avec l’aide de partisans Gourounsi le lieutenant Chanoise battait Babatu a Gandiaga”

p. 48 Political Change in Builsa

1902 Punitive expedition (see original source)

p. 51: The following Builsa chiefs are among those who resigned or were forced out of offices; Akomwob of Kadema, Awumi of Wiaga, Abaagyi of Yekpenyeri Siniensi, Atibil of Kanjaga and Anyimjutee of Fumbisi (Leander Amoak).

At Kadema, Atigbuirou was enskinned as the official chief in place of Akomrob. At Wiaga, Ateng Abooma of Yisobsa was made chief in place of Awuumi of Yimonsa.

p. 52: …at Siniensi, Abadiia Akpiok was appointed chief in place of Abagy. Akninkangnab took the place of Atibil as chief of Kanjarga, while at Fumbisi, Anyiamjutee was replaced by Ayaagyig.

In 1907, the British replaced the military administration with a civil one. Administrative districts were created and Builsa came under the Navrongo Administrative District.

…on 23rd September 1911, Ayieta… was elected paramount chief (Navrongo Districts Record Book, NAG Adm. 63/5/1)

p. 53: …creation of the Native Authority Areas, hegemony of Mamprugu

p. 54: In 1912, Native Authority Areas were created and the Builsas were placed under the Mamprusi Native Authority Area. …the Nayiri became head of the North-eastern province, that is South Mamprusi, Kusasi, Zuarungu and Navrongo Districts. … the Nayiri continued to confirm the elections of Builsa chiefs. The Sandemnab presided over the elections of the chiefs.

p. 55 .The chiefs of Kategra, Jaadem and Kunkuaga preferred the more experience Azinab of Wiaga as paramount chief to the youthful Ayieta… Thus when the Chief Azinab declined to contest the paramountship, they were disappointed. …deposition of the chief of Kanjarga was seriously considered by the District Commissioner.

p. 57f.: (relation to Mamprusi): The chiefs favoured the formation of a separate Builsa division with the Sandem-nab as the president. This decision was derived at meeting held on 19 May, 1934 (came into effect 1st September 1934. … a Builsa Native Authority , a Native Tribunal and a Native Treasures were recognized.

p. 58: Builsa Native Tribunal… with the Sandema-nab as the presiding members. …membership limited up to five…

p. 59: A Builsa Native Treasury was established in Sandema under the Native Treasury Ordinance, 1936. [It]… functioned under the leadership of the Sandem-nab Azantilow until 1951 when the Native Administrations were replaced by District Council and responsibility transfered from the Native Authorities to the Local Councils.

p. 60A Social and Economic Changes

p. 63: A Native Dispensary was opened only in 1937 by the Native Authorities

p. 64: By 1920, a road was constructed from Sandema through Wiaga to Kanjarga and Fumbisi.

… Many Builsa were also enlisted in the Gold Coast Regiment which was formed in 1900. Some of these saw action in Togo, East Africa, India and Burma as members of the West African Frontier Force during the two World Wars.

p. 65: … opening a primary school in 1930 and a dispensary in the 1940 (by White Fathers)

p. 66: … the Kantosis settled in Sandema and Siniensi in the first two decades of the twentieth century.

Bullock-drawn implements were introduced to the Builsa farmers but no interest was shown by the people until the 1950 and 60s.

p. 67: 1935 and 1936 about 200 bulls bred at Pong Tamale were issued to chiefs and farmers in Bulsa and Kusasi for the development of the local breed.

p. 68: Markets were opened in all the Builsa villages and towns. Those in the towns were provided with sheds by the Native Administration.

p. 69: CONCLUSION

p. 71: …the British introduced new foods for example rice which is now a staple…

…Western education has afforded the native the possibility of taking down his own history and particularly allows him to see European rule as an interaction between two sets of people rather than as gods dealing with sub-human beings.

p. 73: APPENDIX; PRIMARY SOURCES (LIST OF INFORMANTS)

1. Mr Abaseba G. Achaab, 45 years, from Kadema, interview: 11/10/82; occupation: teaching

2. Mr. Aboora, 70-75 years; interview: 13/10/82, occupation: farming; Wiaga-Longsa

3. Adum Asaghe: 70-75 years; interview: 15/10/82; occupation: farming, Wiaga-Sinyangsa

4. A. Akardem; 75-85 years, interview: 15/10/82; from Wiaga-Yisobsa-Dogbilinsa, his father: teng-nyono

p. 74:

5. A. Awuchana (now dead); 100 years; interview: 6/10/82; Wiaga-Wobilinsa, Wiaga-Chandem

6. Lawrence Amoak, 65-70 years; interview: 10/10/82; retired catechist, now farmer, W-Chandem

7. Leander Amoak, 65-70 years, interview: 19/10/82, retired teacher, Wiaga-Sinyangsa-Badomssa

8. Lewis Awiadem, 65-70 years, interview: 11/19/82, retired catechist, now farmer, Wiaga-Yisobsa

p. 75: BIBLIOGRAPHY (21 publications)

Pauline Akankyalabey: Geschichte der Bulsa

In: 15 Frauen und 8 Ahnen. Leben und Glauben der Bulsa in Nordghana. (Eds.) M. Grabenheinrich und S. Klocke-Daffa, Münster 2005, p. 29-37.

German (original) Edition

…Ursprünge und Einwanderungen

p. 30

Wie bei vielen Nachbargruppen beginnt auch die Geschichte der Bulsa mit Erzählungen über ihren Ursprung und Einwanderungen aus anderen Gebieten. Ihre heutige Zusammensetzung resultiert daraus, dass sich ganz verschiedene Ethnien unabhängig voneinander im heutigen Bulsagebiet ansie-

p. 31

delten. Im Laufe der Jahrhunderte schmolzen alle zusammen und wurden schließlich eine selbständige kulturelle und politische Einheit. Leider besitzen wir kaum geschichtliches Quellenmaterial über die Bulsa für die Zeit vor dem 20. Jahrhundert und dem Eintreffen der europäischen Kolonialmächte in Nordghana. Unser heutiges Wissen über die frühe Geschichte und Kultur der Bulsa ist daher auf Relikte beschränkt, wie sie sich in traditionellen religiösen Riten (z. B. bei Heiraten und Totenfeiern) und in mündlichen Überlieferungen finden lassen.

Mit Ausnahme der Pionierarbeiten von Rattray (1932) und den Veröffentlichungen über orale Traditionen (als historische Quellen) durch Schott besteht ein allgemeiner Mangel an geschichtlichen Sekundärquellen über die Bulsa. Andererseits steht uns heute über die Sozialstruktur, politische Organisation und Religion dank der Arbeiten von Schott, Kröger, Heermann, Meier und Blanc umfangreiches Material zur Verfügung2. Relevante Quellen aus der Kolonialzeit sind uns als Archivmaterial in der Form von Akten, Urkunden, Briefen, Berichten, Zeitschriften und Gerichtsprotokollen zugänglich.

Unser Wissen über die frühe Geschichte der Bulsa, ebenso wie über die ihrer Nachbarn, basiert nicht auf Faktenmaterial. Es gibt nicht eine einzige historisch völlig vertrauenswürdige Überlieferung. Die Berichte und Erzählungen dienen alle, wie Schott richtig bemerkt, einem politischen, gesellschaftlichen oder religiösen Zweck, und sie können daher alle nur in ihrem jeweiligen Zusammenhang verstanden werden. Sie dokumentieren ein heute noch lebendiges historisches Bewusstsein der Bulsa (SCHOTT 1977: 152).

Schott fand jedoch heraus, dass es sogar innerhalb eines Dorfes unterschiedliche, ja sogar widersprüchliche Versionen historischer Traditionen gibt. Die populärste Ursprungsmythe berichtet vom Entstehen des Atuga-Clans und der Gründung der vier großen Bulsa-Dörfer Sandema, Wiaga, Kadema und Siniensi. Hiernach verließ Atuga, ein Prinz aus der Mamprusi-Hauptstadt Nalerigu, zusammen mit seiner Familie seine Heimat und siedelte an einem Ort, der heute noch Atuga-pusik heißt und zwischen Sandema und Wiaga liegt. Seine vier Söhne Akam, Awiak, Asam und Asinieng gründeten Kadema, Wiaga, Sandema und Siniensi, und deren Söhne sind die Gründer weiterer Untersektionen dieser Dörfer. Sie vermischten sich mit der dort ansässigen Urbevölkerung und nahmen deren Sprache an.

In seiner kurzen Studie über die Bulsa-Traditionen kommt Rattray zu dem Schluss, dass die Bulsa ein Mischlingsvolk (“hotch-potch people”) aus verschiedenen Sprachgruppen sind.

p. 32

Wir haben weder schlüssige Beweise oder Erklärungen für die Züge der Einwanderer, noch wissen wir, wann sie stattfanden und welchem Druck sie gewichen sind. Jedoch ist bekannt, dass die Zeit vom 15. bis zum 18. Jahrhundert eine unruhige Zeit des politischen und sozialen Umbruchs in ganz Nordghana war: Das Entstehen der zentralistischen Königreiche in näherer und weiterer Nachbarschaft der Bulsa (Dagomba, Mamprusi, Nanumba, Gonja, Wa und Mossi), die Einflussnahme des Ashanti-Reiches auf ihre nördlichen Nachbarn und der transatlantische Sklavenhandel hatten sicher einen großen Einfluss auf die demographischen Strukturen Nordghanas.

Die frühe soziale und politische Organisation im Bulsaland

Eine Folge der Einwanderungswellen war, dass die Bulsa seitdem aus zwei großen Abstammungsgruppen bestehen, die friedlich Seite an Seite leben. Es sind die Nachkommen der Urbevölkerung und die Nachkommen Atugas und anderer Einwanderungsgruppen. Allen gemeinsam ist, dass sie in Verwandtschaftverbänden leben, die sich vom Clan bis hin zum einzelnen Gehöft in viele Einzelgruppen verzweigen, ohne dass dieses System eigentlich eines starken Häuptlingstums bedurfte. Über einen jeweils größeren Siedlungsverband hatte wenigstens früher ein Erdherr oder Erdpriester einen starken Einfluss, vor allem im religiösen Leben. Oft war er ein Nachkomme der ursprünglichen Bewohner. Seine Hauptaufgabe bestand darin, als Mittler zwischen den Menschen und der Erde zu walten. Als Aufseher und Opferer der Erdheiligtümer, der nach Bulsa-Glauben streng auf die Einhaltung der Moral und besonderer Tabuvorschriften achtete, hatte er Einfluss auf viele Dinge des täglichen Lebens und war für das Wohlergehen seiner Gemeinschaft mitverantwortlich.

Der Erdherr war aber nicht die einzige Autorität im vorkolonialen Bulsaland. Die Nachkommen Atugas sollen angeblich eine Art Häuptlingstum errichtet haben, das sie in einer sakralen Form noch an ihr Ursprungsland und an den Häuptling der Mamprusi (Nayiri) gebunden hat.

Die Bulsa-Häuptlinge besaßen ebenso wie die Erdherren eine rituelle Autorität. Sie konnten Land verteilen, in Streitfällen des eigenen Clans vermitteln und sogar im Falle eines Angriffs von außen Krieger zur Verteidigung des Landes rekrutieren. Es muss jedoch betont werden, dass der Häuptling

p. 33

keine politische Verfügungsgewalt über Personen hatte, die nicht zu seinem Clan oder seiner Verwandtschaftsgruppe gehörten. Dieser Mangel an ausübender Gewalt auf Seiten der Häuptlinge passte der britischen Kolonialverwaltung nicht in ihr Konzept und führte zu der Vermutung, dass die Bulsa und andere Ethnien früher überhaupt keine Häuptlinge hatten und dass das ganze Gebiet sich in einem gesetzlosen Zustand befand (DER 2000). In den mündlichen Bulsa-Überlieferungen wird jedenfalls berichtet, dass alle Dörfer des Atuga-Clans schon eine Art Häuptlingstum kannten.

Die Sklavenjagden der Zabarima und der Übergang zur kolonialen Epoche

Schriftliche Quellen berichten, dass Sklavenjagden im heutigen Nordghana schon seit dem 18. Jahrhundert stattfanden (AWEDOBA 1985, S. 57). Der Brite Bowdich, der 1817 Kumasi besuchte, berichtete, dass das Königreich Dagomba (Nordghana) jedes Jahr 500 Sklaven und andere Güter als jährlichen Tribut an das Ashanti-Reich senden musste (BOWDICH 1819, S. 320). Auch Goody schreibt, dass Völker des heutigen Nordghana von Mossi (heute in Burkina Faso) und den südlicheren Königreichen überfallen wurden (GOODY 1967). Übereinstimmend aber erklären die genannten Quellen, dass die frühen Sklavenjagden weder das militärische noch das räumliche Ausmaß der Zabarima-Raubzüge zwischen 1894 und 1898 erreichten.

Die Zabarima (auch Djerma genannt, aus dem Gebiet des heutigen Niger), die zum ersten Mal in den 1860er Jahren als Pferdehändler und Kaufleute bei den Dagomba-Häuptlingen auftraten, errichteten später ihr Hauptquartier in Kasana (bei Tumu). Sie fühlten sich nun unabhängig von den Dagomba und überfielen von dort benachbarte Ethnien. Unter ihrem späteren Anführer Babatu erreichten die Sklavenjagden ihren Höhenpunkt. Die Zabarima mit ihren Hilfstruppen aus Nordghana griffen ein Dorf nach dem anderen an, töteten die Häuptlinge, nahmen Männer und Frauen gefangen, verkauften sie als Sklaven und beschlagnahmten ihre ganze Habe: Vieh, Getreidevorräte usw. Aber die Völker Nordghanas waren nicht immer so wehrlos wie oft angenommen. Unter Führung des Sandema-Häuptlings sollen vereinigte Bulsa-Truppen die Zabarima zweimal geschlagen haben (MORRIS 1902).

p. 34

1901 erklärte Großbritannien Nordghana zum Protektorat. Allgemein lässt sich sagen, dass die Briten den Norden vernachlässigten und seine Entwicklung wenig förderten. Sie nahmen an, dass die Nordterritorien wirtschaftlich nichts einbrachten, da man hier im Vergleich zu Südghana weder Bodenschätze ausbeuten noch landwirtschaftliche Überschüsse erzielen konnte.

Da die Zabarima-Überfälle das Land politisch, wirtschaftlich und sozial zerrüttet hatten, hielt die Verwaltung es für dringend erforderlich, dass alle weiteren Fehden und Überfälle eingestellt wurden, damit in einem befriedeten Land ein neuer Handel und Wandel aufblühen konnte. Dieses erreichten die Briten zum Teil dadurch, dass sie Strafexpeditionen gegen angebliche Unruhestifter durchführten, um die Bevölkerung ganz unter ihre Kontrolle zu bekommen. Zwei solcher Expeditionen wurden gegen die Leute von Sandema ausgeschickt mit dem Erfolg, dass sich schließlich der Häuptling von Sandema ergab und um die britische Flagge bat.

Die Kolonialverwaltung brauchte nicht nur Rekruten, sondern auch Menschen, die Lasten trugen und Straßen, Bahnhöfe und Rasthäuser für sie bauten. Schon 1906 begann man, Arbeiter für die Goldbergwerke von Tarkwa im Süden anzuheuern. Um 1917 bestätigten die Behörden, dass ungefähr 90% der Polizisten aus Northerners (Leute aus dem Norden) bestand. Obwohl das beständige Anheuern von Arbeitskräften für Bergwerke und Eisenbahnen des Südens schädlich für die Leute im Norden war, argumentierten die Kolonialbeamten, dass dieses ein geeignetes Mittel war, “sich eine aufgeklärtere Weitsicht anzueignen als es bei einem lebenslangen Aufenthalt innerhalb der Grenzen eines kleines Distriktes” möglich gewesen wäre (HOWELL1997, S. 40). 1927 wurde dem Anheuern von Arbeitskräften endgültig ein Ende gesetzt. Die Kolonialbehörden sahen ein, dass die Politik der Zwangsarbeit jeden wirtschaftlichen Fortschritt in der Heimat der Arbeiter blockierte (THOMAS 1973).

Aus dem Bedarf an Arbeitskräften für die Briten ergab sich die Notwendigkeit, geeignete Führer zu finden, die diese Arbeiter rekrutierten. Zu ihrem Ärger besaßen die meisten traditionellen Führer nicht genug politische Macht, auf ihre Leute Zwang auszuüben. Die britischen Beamten verkannten jedoch die Machtbefugnis der Häuptlinge und beschwerten sich beständig über die Unfähigkeit der Häuptlinge, angemessen zu regieren. Als Ausweg aus diesem Dilemma blieb der Kolonialverwaltung nichts anderes übrig als die Autorität der Häuptlinge zu stärken, neue Häuptlingstümer zu schaffen

p. 35

und, falls notwendig, unbotmäßige Häuptlinge abzusetzen (RATTRAY 1932). Hierdurch wurde der Charakter des Häuptlingstums verändert: Aus einer eher religiösen wurde in stärkerem Maße eine politische Einrichtung. Die Häuptlinge und Unterhäuptlinge wurden in Stellungen befördert und mit Autorität versehen, wie sie niemals zuvor in der Bulsa Geschichte bekannt waren. Dieses führte in einigen Fällen zum Missbrauch ihrer Macht, die sich durch Korruption und Unterdrückung der Untertanen äußerte. Die Einführung der Geldwirtschaft und die Besteuerung der Bevölkerung führte dazu, dass viele Menschen nach Süden migrierten, um dort Geld zu verdienen, weil es im Norden zu wenige Arbeitsplätze gab. 1911 rief die Kolonialadministration eine Versammlung aller Bulsa-Häuptlinge ein, und Ayieta Ananguna, der Häuptling von Sandema, wurde zum Paramount Chief (etwa gleichbedeutend mit Oberhäuptling oder König) aller Bulsa befördert. 1934 wurde das Bulsaland eine eigene Verwaltungseinheit (Bulsa Native Authority Area) mit einem eigenen Gericht (Native Tribunal) unter dem Paramount Chief .

Westliche Schulbildung und Christentum

Die Einstellung der Kolonialregierung gegenüber der Einführung westlicher Schulbildung im Norden war eher zurückhaltend, um so die Macht der traditionellen Institutionen zu erhalten. Lediglich die Kirchen unterhalten einige wenige Schulen. Die Konsequenz daraus war eine erhebliche und bis heute bemerkbare Bildungsbenachteiligung des Nordens gegenüber den Ashantigebieten und dem Süden (THOMAS 1975, S.427).

Tatsächlich verdanken viele der ersten gebildeten Bulsa und darüber hinaus viele andere Bewohner Nordghanas ihre Ausbildung den Weißen Vätern, die sich 1906 erstmals in Navrongo niederließen und 1907 eine Schule eröffneten. Trotz eines anfänglichen Misstrauens und Desinteresses seitens der Bevölkerung stieg die Nachfrage kontinuierlich an, jedoch wurden die Bemühungen der Weißen Väter um neue Stationen und Schulgründungen von der Kolonialverwaltung kategorisch abgelehnt.

Erst 1927 erhielten die Weißen Väter die Erlaubnis, eine Schule in Wiaga (Bulsaland) zu eröffnen. 1936 eröffnete die Bulsa Native Authority auf Drängen des Sandema-Häuptlings eine eigene Grundschule in Sandema. Bis 1932 gab es in den gesamten Northern Territories lediglich vier Missionsschulen und vier staatliche Grundschulen, eine Junior Trade School und eine weiterführende Schule, während allein das Ashantigebiet 46 staatliche und 68 nicht-staatliche Schulen zählte. Die restriktive Politik dieser Zeit wurde in den 30er Jahren gelockert, als eine stärkere Missionstätigkeit im Norden zugelassen wurde. Die Weißen Väter nutzten die Gelegenheit für die Gründung von Missionsstationen und Schulen auch in anderen Teilen des Protektorats.

Insgesamt wirkte sich die Politik der Kolonialadministration negativ auf die Verbreitung von Schulen und westlicher Schulbildung im Norden aus. Darüber hinaus hatte sie auch ihren Anteil an der geringen Beteiligung von Mädchen am Schulsystem. Das anfängliche allgemeine Desinteresse der Kolonialbehörden, Mädchen für den Schulbesuch zu gewinnen, sowie die Zurückhaltung der Eltern, ihre Töchter zur Schule zu schicken, drückt sich anschaulich in Zahlen aus: Bis 1920 waren von den insgesamt 243 Schülern in den gesamten Northern Territories lediglich 9 Mädchen, bis 1938 hatten nur 38 Mädchen dieser Region den Standard VII Level erreicht. In Ashanti waren es zur gleichen Zeit 337. Abschließend kann man festhalten, dass der Norden im Hinblick auf die Schulbildung – insbesondere von Mädchen – im Vergleich zum Süden stark benachteiligt war, was bis heute Auswirkungen hat.

Pauline Akankyalabey: History of the Bulsa

In: 15 Wives and 8 Ancestors. Life and Faith of the Bulsa in Northern Ghana. (Eds.) M. Grabenheinrich and S. Klocke-Daffa, Münster 2005, p. 29-37.

English Translation (Deeple and F.K.)

… p. 30

Origins and immigration

As with many neighbouring groups, the history of the Bulsa begins with narratives of their origins and immigrations from other areas. Their present composition is the result of very different ethnic groups settling independently in what is now the Bulsa area.

p. 31

settled. In the course of the centuries they all melted together and finally became an independent cultural and political unit. Unfortunately, we have hardly any historical source material on the Bulsa for the time before the 20th century and the arrival of the European colonial powers in Northern Ghana. Our current knowledge of the early history and culture of the Bulsa is therefore limited to relics as found in traditional religious rites (e.g. at marriages and funeral ceremonies) and in oral traditions.

With the exception of the pioneering work of Rattray (1932) and the publications on oral traditions (as historical sources) by Schott, there is a general lack of historical secondary sources on the Bulsa. On the other hand, we now have extensive material on social structure, political organisation and religion thanks to the work of Schott, Kröger, Heermann, Meier and Blanc2. Relevant sources from the colonial period are available to us as archival material in the form of files, deeds, letters, reports, journals and court records.

Our knowledge of the early history of the Bulsa, as well as that of their neighbours, is not based on factual material. There is not a single historically completely trustworthy tradition. The reports and narratives all serve a political, social or religious purpose, as Schott rightly points out, and they can therefore all only be understood in their respective contexts. They document a historical consciousness of the Bulsa that is still alive today (SCHOTT 1977: 152).

Schott found, however, that even within one village there are different, even contradictory versions of historical traditions. The most popular origin myth reports the emergence of the Atuga clan and the founding of the four large Bulsa villages of Sandema, Wiaga, Kadema and Siniensi. According to this, Atuga, a prince from the Mamprusi capital of Nalerigu, left his home together with his family and settled in a place that is still called Atuga-pusik and lies between Sandema and Wiaga. His four sons Akam, Awiak, Asam and Asinieng founded Kadema, Wiaga, Sandema and Siniensi, and their sons are the founders of other sub-sections of these villages. They mixed with the indigenous population there and adopted their language.

In his brief study of Bulsa traditions, Rattray concludes that the Bulsa are a mixed race (“hotch-potch people”) of different language groups.

p. 32

We have no conclusive evidence or explanation of the immigrant traits, nor do we know when they took place and to what pressures they gave way. However, it is known that the period from the 15th to the 18th century was a turbulent time of political and social upheaval throughout northern Ghana: the emergence of the centralist kingdoms in the immediate and wider neighbourhood of the Bulsa (Dagomba, Mamprusi, Nanumba, Gonja, Wa and Mossi), the encroachment of the Ashanti Empire on their northern neighbours, and the transatlantic slave trade certainly had a major impact on the demographic structures of northern Ghana.

Early social and political organisation in Bulsaland

One consequence of the waves of immigration was that the Bulsa have since consisted of two major descent groups living peacefully side by side. They are the descendants of the original population and the descendants of Atuga and other immigrant groups. What they all have in common is that they live in kinship groups that branch out into many individual groups, from clans to individual homesteads, without this system actually requiring a strong chiefdom. At least in the past, an earth lord or earth priest had a strong influence over a larger settlement, especially in religious life. Often he was a descendant of the original inhabitants. His main task was to act as a mediator between the people and the earth. As overseer and sacrificer of the earth sanctuaries, who, according to Bulsa beliefs, strictly observed morality and special taboo rules, he had influence on many things in daily life and was jointly responsible for the well-being of his community.

The Earth Lord was not the only authority in pre-colonial Bulsaland, however. Atuga’s descendants are said to have established a kind of chieftaincy that still bound them in a sacred form to their land of origin and to the Mamprusi (Nayiri) chief.

Like the earth lords, the Bulsa chiefs possessed a ritual authority. They could distribute land, mediate in disputes of their own clan and even recruit warriors to defend the land in case of an attack from outside. It must be emphasised, however, that the chief

p. 33

had no political authority over persons who did not belong to his clan or kinship group. This lack of exercising power on the part of the chiefs did not fit into the British colonial administration’s concept and led to the assumption that the Bulsa and other ethnic groups had no chiefs at all in the past and that the whole area was in a lawless state (DER 2000). In any case, oral Bulsa traditions report that all villages of the Atuga clan already knew some kind of chieftaincy.

The Zabarima slave raids and the transition to the colonial era

Written sources report raids had been taking place in what is now northern Ghana since the 18th century (AWEDOBA 1985, p. 57). The Briton Bowdich, who visited Kumasi in 1817, reported that the Dagomba Kingdom (Northern Ghana) had to send 500 slaves and other goods each year as annual tribute to the Ashanti Empire (BOWDICH 1819, p. 320). Goody also writes that peoples of today’s Northern Ghana were invaded by Mossi (today in Burkina Faso) and the more southern kingdoms (GOODY 1967). In agreement, however, the above sources state that the early slave raids did not reach the military or spatial scale of the Zabarima raids between 1894 and 1898.

The Zabarima (also called Djerma, from the area of present-day Niger), who first appeared in the 1860s as horse traders and merchants at the Dagomba chiefs, later established their headquarters in Kasana (near Tumu). Then they felt independent of the Dagomba and raided neighbouring ethnic groups from there. Under their later leader Babatu, the slave hunts reached their peak. The Zabarima with their auxiliaries from Northern Ghana attacked one village after another, killed the chiefs, captured men and women, sold them as slaves and confiscated all their belongings: Livestock, grain stocks, etc. But the peoples of northern Ghana were not always as defenceless as often assumed. Under the leadership of the Sandema chief, combined Bulsa troops are said to have defeated the Zabarima twice (MORRIS 1902).

p. 34

In 1901, Great Britain declared Northern Ghana a protectorate. In general, it can be said that the British neglected the North and did little to promote its development. They assumed that the Northern Territories were economically useless because they could not exploit mineral resources or produce agricultural surpluses compared to Southern Ghana.

Since the Zabarima raids had disrupted the country politically, economically and socially, the administration considered it imperative that all further feuds and raids cease so that new trade and change could flourish in a pacified land. The British achieved this in part by conducting punitive expeditions against alleged troublemakers in order to bring the population entirely under their control. Two such expeditions were sent against the people of Sandema with the success that the chief of Sandema finally surrendered and asked for the British flag.

The colonial administration needed not only recruits but also people to carry loads and build roads, stations and rest houses for them. As early as 1906, workers began to be hired for the Tarkwa gold mines in the south. By 1917, the authorities confirmed that about 90% of the police force was made up of Northerners (people from the North). Although the constant hiring of labour for Southern mines and railways was harmful to Northerners, colonial officials argued that it was a suitable means of acquiring “a more enlightened foresight than would have been possible by a lifetime’s residence within the boundaries of a small district” (HOWELL 1997, p. 40). In 1927, the hiring of labour was finally put to an end. The colonial authorities realised that the policy of forced labour blocked any economic progress in the workers’ homeland (THOMAS 1973).

The need for labour for the British resulted in the need to find suitable leaders to recruit these workers. To their chagrin, most traditional leaders did not possess enough political power to exert coercion on their people. However, the British officials misjudged the power of the chiefs and consistently complained about the chiefs’ inability to govern adequately. As a way out of this dilemma, the colonial administration had no choice but to strengthen the authority of chiefs, create new chiefdoms

p. 35

and, if necessary, remove insubordinate chiefs (RATTRAY 1932). This changed the character of chieftaincy: From a more religious institution it became to a greater extent a political one. The chiefs and sub-chiefs were promoted to positions and given authority never before known in Bulsa history. This led in some cases to the abuse of their power, which manifested itself in corruption and oppression of the subjects. The introduction of a cash economy and taxation of the population led to many people migrating south to earn money because there were too few jobs in the north. In 1911, the colonial administration called a meeting of all Bulsa chiefs and Ayieta Ananguna, the chief of Sandema, was promoted to Paramount Chief (roughly equivalent to head chief or king) of all Bulsa. In 1934, Bulsaland became a separate administrative unit (Bulsa Native Authority Area) with its own court (Native Tribunal) under the Paramount Chief .

Western education and Christianity

The colonial government’s attitude towards the introduction of Western schooling in the North was rather cautious, in order to preserve the power of the traditional institutions. Only the churches maintained a few schools. The consequence of this was a considerable educational disadvantage in the North compared to the Ashanti areas and the South, which is still noticeable today (THOMAS 1975, p. 427).

In fact, many of the first educated Bulsa and, moreover, many other inhabitants of northern Ghana owe their education to the White Fathers, who first settled in Navrongo in 1906 and opened a school in 1907. Despite initial mistrust and disinterest on the part of the population, demand increased steadily, but the efforts of the White Fathers to establish new stations and schools were categorically rejected by the colonial administration.

It was not until 1927 that the White Fathers received permission to open a school in Wiaga (Bulsaland). In 1936, the Bulsa Native Authority opened its own primary school in Sandema at the insistence of the Sandema chief. By 1932, there were only four mission schools and four government primary schools, one junior trade school and one secondary school in the entire Northern Territories, while the Ashanti Territory alone had 46 government and 68 non-government schools. The restrictive policies of this period were relaxed in the 1930s when more missionary activity was allowed in the north. The White Fathers took the opportunity to establish mission stations and schools in other parts of the protectorate.

Overall, the colonial administration’s policy had a negative impact on the spread of schools and Western schooling in the North. Moreover, it also had its share in the low participation of girls in the school system. The initial general disinterest of the colonial authorities in attracting girls to attend school and the reluctance of parents to send their daughters to school is vividly expressed in figures: By 1920, out of a total of 243 pupils in the entire Northern Territories, only 9 were girls; by 1938, only 38 girls in this region had reached Standard VII level. In Ashanti, at the same time, there were 337. In conclusion, the North was at a severe disadvantage in terms of schooling – especially of girls – compared to the South, and this continues to have an impact today.

Akankyalabey, Melanie (Ed., Sub Committee Chairperson)

[The Catholic Mission of Wiaga] Title Page missing

(Note F.K: Only a raw draft with handwritten additions and corrections was available to me, some of which were illegible in my copies. Cf. also, BULUK no 4 (2005) Main Feature: Religions and Missions among the Bulsa, F. Kröger: pp. 44-48; M. Abaala (History of Wiaga Clinic): pp. 49-50).

p. 4 (?)

History of Wiaga Parish (St. Francis Xavier)

Introduction

Wiaga Parish was the third parish to be opened in the Navrongo-Bolgatanga Diocese in April 1927 by the White Fathers (Missionaries of Africa) under the pastorship of Rev. Father Dagenais, Rev. Father Champagne and Rev. Brother Albert.

The White Fathers Society was founded in 1868 in Algeria by a Frenchman (Cardinal Lavigerie, the Archbishop of Algiers.

They began to evangelise from North Africa down the Sahara Desert to the Sudan with a Caravan – when suddenly they were attacked and killed by the Tuaregs…

In 1899, Rev. Father Chollet (Superior of the White Fathers) together with Rev. Father Oscar Morin succeeded to settle at Navrongo in 1906 to open the 1st Parish in the Northern Territories.

The Vatican Authorities from Rome wanted to separate the Catholic Missions of the English Colonies of the Northern Territories to have their own control and supervision.

An Apostolic Vicar was appointed (Rev. Bishop Oscar Morin) the overseer of Missionary Activities in the Northern Territories. He was mandated to open two more parishes in the Northern Territories.

In February 1925, he opened the second Parish in Bolgatanga and two years later the third Parish was opened in Wiaga and named St. Theresa.

Later another new station was opened in Nandom, the White Fathers in Wiaga were transferred from Wiaga to Nandom and the Wiaga parish closed down due to lack of personnel, to little positive impact and little involvement of the traditional people.

In 1939 the set backs were reviewed and the parish re-opened by the Apostolic Vicar (Rev. Bishop Oscar Morin) under …two priests (Rev. Father Contu and Rev. Father Paul Laval).

The Wiaga Parish was then named St. Francis Xavier.

NAMES OF THE WHITE FATHERS WHO HAVE WORKED IN WIAGA PARISH

1. Rev. Bishop Oscar Morin (RIP)

2. Rev. Father Contu (RIP)

3. Rev. Father Laval (RIP)

4. Rev. Father Charles Gagnon (RIP)

5. Rev. Father Glover (RIP)

6. Rev. Father Dazini (RIP)

7. Rev. Father Lamien

8. Rev. Father Philip Marneffe (RIP)

9. Rev. Father Van den Haute

10. Rev. Father van den Hoven (RIP)

11. Rev. Father Guitet

12. Rev. Father Théraut

13. Rev. Father Coningham

14. Rev. Father Kervin

15. Rev. Father Damien

16. Rev. Father Heinrich Kirschner (RIP)

17. Rev. Father Grosskinsky

DIOCESE PRIESTS WHO WORKED IN WIAGA PARISH

1. Rev. Father Richard Pwaman (RIP)

2. Rev. Father Camilo Sarko

3. Rev. Father John Asoedena (RIP)

4. Rev. Father Peter Azenab

WIAGA PARISH NATIVE PRIESTS

No NAME ORDAINED REMARKS

1. Rev. Father Peter Azenab, 1st April 1962 Laicised

2. Rev. Father Percy Abandin 18th December 1982 RIP

3. Rev. Father Alfred Agyenta 6th August 1988 Further studies

4. Rev. Father Ignatius Anipu 1991 UK

5. Rev. Father Emmanuel Adeboa 29th July 1995 Tanzania

6. Rev. Father Andrew Anab 1996 Niger

7. Rev. Father Caesar Atuire 1997 Rome

8. Rev. Father Joshua Gariba 1998 Accra Diocese

9. Rev. Father David Akanbang 15th July 2001 Bolgatanga

10. Rev. Father Thomas Achambe still to become priest, Congo

OUTSTATIONS

1. Sandema, opened 1952

2. Fumbisi, opened 1945

3. Kanjarga

4. Chuchuliga

5. Wiesi – Gbedembilisa

6. Siniensi – Doninga

7. Kadema Chansa

8. Gbedema

Schools under the supervision of the Catholic Education Unit (CEU) Wiaga Parish

Circuit Pre-schools Primary J.S.S Total

Wiaga Kadema 4 8 2 14

Sandema 1 1 0 2

Chuchuliga 2 2 1 5

Kanjarga 2 2 0 4

Fumbisi 1 1 0 1

Total 10 14 3 27

OTHER SCHOOLS

St: Martin’s De Porres Middle school was established in 1957/58, which later became a continuation and finally a Junior Secondary School in 1997.

Azenab Girls Primary was established in 1970 for only girls.

Wiaga Day Care, which was established in 1980 to take care of the Pre-school pupils (Boys/Girls)

The shepherd schools were established in 1990 by the late Rev. Van den Hoven and late Gerald Atayaaba… Presently these shepherd schools have been mainstreamed into the Regular Education system. They were thirty-one schools spread throughout the District. The total enrolment recorded was 3,854 Children with Boys = 2,451 and Girls = 1,403…

LOCAL MANAGERS

1. Dominic Awindok retired

2. Melanie Akankyalabey 1996 to date

Asianab, Francis Afoko (Private Notes): The Ayietas (1970)

Copied by J. Agalic with permission Nov. 1975, transcribed by Rüdiger Schott (RS), Bonn, April 2005 with some comments by James Agalic 1 Further comments and additions by Franz Kröger (“FK” in footnotes). Further comments and corrections by Robert Asekabta (RA). The page numbers (e.g. p.2, p.3…) refer to Agalic’s and Schott’s copy, not to the original manuscript.

[pages 10 and 11 of the original maunscript are missing!]

footnote 1 (RS)

[?] means 1. writing illegible, 2. sense of the word or the sentence is not clear. Added words or phrases are put in square brackets [ ]. Obvious misspellings have been corrected.

p. 2:

In the days of Abil, founder of Gaadem, lower Sandema, now called Abilyeri, the people recognized Achoek [RS: Achiok?] of Awusuiyeri as chief. Achoek was a strong and wealthy man. He ruled with iron hands and for punishment he would go to the extent of pulling down crops of his subjects.

This chief became so unbearable that the chief makers and subjects came together and deskinned him. In place of Achoek, Abil was made chief. Abil was also a wealthy man who was very liberal and so admired by the people of Sandema. Abil ruled for many years and brought up of a family as shown below:

ABIL

↓

ABACHUA

↓

ANAMBASI

↓

ANAGUNA

↓

APOTEBA

↓

ANAMKUM

From the reign of Abil, succession followed down to Anamkum in about 1850.

It was during the reign of Anamkum that the notorious slave Raider, Babatu started his exploits in this part of the country through the North West by way of Bachongsa.Babatu fought and broke up villages like Bachongsa, Doninga, Vare, Kanjarga and Fumbisi. People fleeing for safety massed into Sandema for help.

Babatu had information and tried to march into the town through Chana. There was a battle between the slave raiders and Sandema people at Fiisa where the raiders were beaten off with heavy casualties. Up to date, the scene of the battle can be easily seen by the remnants of Dane gun butts and barrels left behind by the retreating invaders can still be seen in the area. This did not deter Babatu from making [a] further attempt at breaking up Sandema.

[In the] meantime Anankum had organised the people of Kadema, Wiaga, Siniensi and Sandema into a strong force. And when Babatu next made an attack from Kanjarga

p. 3: – Gbedema direction, one rainy season about harvest time, the battle cry went out and a fierce battle was fought at Suwarinsa bordering Wiaga.

This was the decisive battle and when Babatu lost, he never came back again till the coming of the »white man« to this district. An[d] this was the beginning of the building of the Builsa state with Sandema as the seat of Government about the year 1890.

At about this time there was news of the »white man» in this part of the country. Unfortunately Anankum did not live to see one (white man) before his death. Unlike his predecessors who had [led] a peaceful peasant life, Anankum fought tribal wars and Babatu of legendary [?] Anankum died after a long reign and among his sons were Ayieta who later succeeded him, Adong and Agbanvuuk. By his death, Builsa had lost a protector and Sandema a leader and a father. For almost five years there was no official successor. This vacuum would have lasted longer but for the coming of the white man (the British).

The making of a chief (footnote 2)

[Ayieta]