CHAPTER VI

EXCISION AND CIRCUMCISION

1. INTRODUCTION TO CHAPTER VI

1.1 Questions concerning terminology

After 1978, with the growth of the literature on female circumcision or excision, ‘female genital mutilation’ (FGM) was generally accepted as the name of all types of female genital operations. This term is often defined as follows:

Partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons (WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA 1997).

However, some have raised concerns about FGM as a term. For example, in 2005, Obioma Nnaemeka, an African feminist, argued that this term ‘introduced a subtext of barbaric African and Muslim cultures and the West’s relevance (even indispensability) in purging it [endnote 1]’.

The term ‘female circumcision’, which is still frequently used (by Nnaemateka and myself in the 1st edition), is often rejected, especially by feminists, for expressing too great of an equivalence between male and female circumcision. The cruelty and extent of female circumcision far surpasses male circumcision, and its physical and psychological after-effects are much more severe.

For the Bulsa, according to their practice of FGM, even in more recent definitions, the name ‘excision’ fits. Excision is defined by Wikipedia (p. 5) under Type II of FGM as ‘removal of the clitoral glans and inner labia’ [endnote 2]. Regarding the removal of the ‘outer labia’, I received varying information from Bulsa informants, but Knudsen (1994: 148) was able to observe such operations among them.

1.2 Methodological difficulties in the collection of material {198}

If participation in other Bulsa rites already causes difficulties for the stranger, the mistrust, fear, shyness and feelings of inferiority of those concerned often increase when he wants to participate in an excision ceremony or asks a girl about her excision. Some reluctance may be due to the gender difference between the male researcher and the female respondents, and some because excision was banned under President Kwame Nkrumah (See endnote 41). However, the cultural difference between the European observer (i.e. the questioner) and the Bulsa girl probably weighs most heavily. The girls know that excision does not exist in Europe and that most Europeans consider the practice cruel and barbaric.

Thus, it was impossible for me before 1978 to observe the excision activities throughout their course. I could only gain insight through a brief visit to the ritual site shortly after excision while kept at a distance of about 100 metres. This visit was more suitable for getting to know the general atmosphere and accompanying circumstances (e.g. place, time, number of people) than the individual ritual procedures of action in more detail.

The ethnographic data recorded below have been obtained through various working methods.

1. The most productive method was the oral interview, which, however, only three excised girls (the schoolgirls Azuma and Felicia and the illiterate Aguutalie) [endnote 3] agreed to it after initial hesitation {199}. Then, however, they answered even the most intimate questions without great shyness, sang appropriate songs on the tape recorder and demonstrated body positions and ritual actions without any special prompting.

2. Several excised girls were willing to talk about their excision but did not want to face the stranger directly in an oral interview. As such, I instructed three young male Bulsa to ask them to write down a free-written account of their excision or, if they could not write, to speak it in Buli on my tape recorder. They were also asked to answer 14 standard questions. These questions were primarily aimed at external facts about the excision (e.g. place of excision, time, age, number of girls, married or single, escort, circumciser). Only the last two questions were intended to ask about the girls’ attitudes towards their excision. Thus, 15 free reports and 15 completed questionnaires came into my possession. It is clear to me that the questionnaires, in particular, have limited scientific value, as the 15 interviewees could not be sampled in a genuinely random method [endnote 4]. In particular, the statements about personal attitudes are highly subject to falsification, as girls who felt little to no deep shame about their excision would be more likely to participate in an interview. Therefore, no attempt at a quantitative evaluation will be made here.

3. To supplement this, male persons who participated in the excision, such as the excised girl’s classificatory fathers or brothers, were also interviewed and asked to write a report {200}.

4. I gathered that I was not a major disruptive factor at the only excision I entirely observed in 1988. My companion, the compound head, insisted that I take my camera with me. However, I limited my photographic recordings to the rites following the operation.

After arriving at the two women’s compound, their husbands each thanked me for my ‘help’ (maaka).

2. EXCISION IN BULSALAND

To my knowledge, the following circumcisers (ngaridoba, sing. ngarido) were performing excisions in the Bulsa area:

1. An elderly Bulo from Chuchuliga who a younger man from Chana helps during busy times

2. An Islamic Kantussi woman (about 40–50 years old) from Chana-Katiu

3. A young man from Bolgatanga

The Kantussi woman from Katiu gave information about her ‘office’ and work. The occupation of excising is hereditary in her family. She inherited it from her father and will pass it on to the most able of her children. She circumcises boys (circumcision of the foreskin) and girls (clitoridectomy) and cuts tribal marks. Among the Bulsa, however, she only performs female excisions between October and April, mainly in October.

These dates mostly align with the statements by the other informants. The 15 girls interviewed gave the following information about the month they were excised: October: 2, November: 3, December: 5, January: 1, February: 2, March: 1, “I don’t know”: 1.

When I wanted to attend an excision in Fumbisi at the end of December (1973), the circumciser told me that most of the girls of this excision period (in the dry season) were already excised {201} and only a few were still expected.

There are no exact guidelines for the appropriate age of the girls (kaliak, pl. kalaasa) to be excised, but it is probably mostly between physical maturation and marriage. Of the girls who gave me information, the youngest was 12 at the time of excision, and the oldest was 17. The 17-year-old girl emphasised that she was the oldest of her whole excision group. One girl from Sandema-Kori did not initially get permission from her parents to be excised because she was too young. She ran to the circumciser alone. The parents followed later, and the circumciser convinced them their daughter was already the right age. This example shows that even among the Bulsa, there are often different opinions about the right age for excision. The example also shows that the impetus for excision usually comes from the girl herself.

Even if the parents repeatedly advise their daughter to be excised and sometimes even apply pressure, the attitude of the girl herself is ultimately decisive. However, no circumciser will perform an excision unless classificatory parents or relatives of the house appear and consent. I know of only one case where the circumciser did not wait for the companion group from the girl’s house to arrive. Azuma from Wiaga-Chiok ran to a compound in Chuchuliga where a woman from her house (in Chiok) was married. When her relatives from Chiok (another wife of her father and a brother) were waiting, Azuma was excised before they arrived, with the consent of the ‘aunt’ from Chuchuliga.

If the girl is already married, the husband and the yeri-nyono of the house will also have to consent to the excision. If she is a doglie (cf. p. {41} and {388}) in the house of her father’s sister, the impulse sometimes comes from this woman, and without her consent, excision is not possible.

The girls stated the following about their motivations for excision:

1. My mother was excised, [and] my grandmother was excised; it was always like that with us. That’s why I also want to be excised {202}.

2. If you are excised, you will no longer be insulted by men and excised women for being a man, i.e. only through excision can you become a real woman [endnote 5].

3. An excised girl will more easily get a man for coitus (before and during marriage).

4. I want to be different from other unexcised girls.

5. If you are excised, you will have an easy birth later.

6. If I am excised, I will later receive the funeral of a woman and not that of a man, as is the case with unexcised women [endnote 6].

Motives 2 and 3 are related; some Bulsa prefer to have intercourse with excised girls because of their perceived greater femininity. This double reason seems to be the most influential motive besides the purely traditionalist first one.

The girl mentioned above from Sandema-Kori, who ran to the circumciser prematurely against her parents’ wishes, was in this hurry because she wanted to get married. However, she did not dare to marry unexcised. After all, she had once overheard her brother criticising one of his wives, calling her a man because she had never been excised. Towards the end of her account, my informant, in turn, insults all unexcised girls:

Those girls who go about after men and have not been excised are stupid girls to me. If I were a man, I would not use my penis on them at all {203}.

Although it was claimed above that the impetus for excision almost always comes from the girls or at least happens with their complete consent, I have become aware of a case where a girl who had left school was forced to undergo this operation by her parents (2022) .

Atani (name changed) accused a married man of sexual harassment. The man denied this and asked a tanggbain to punish the culprit in this conflict. This act was considered a curse (kaka). Atani then behaved like a boy, took part in their games and broke all the pots her mother had in stock. Her mother punished her daughter by forcing her to undergo excision, even though they feared that the tanggbain might kill her because of the curse. Following her excision, she started bleeding heavily. A visit to a diviner (baano) and an examination by a local midwife revealed that the reason for the bleeding was a pregnancy that ended in a miscarriage. Severe complaints (for example, dizziness) persisted afterwards. The accused man then revoked his curse through the pirintika [revoking] ritual, and Atani also underwent this ritual and confessed that she had falsely accused the man.

3. EXECUTION OF FEMALE EXCISION

If girls have decided to undergo excision, they can inform their parents. However, they sometimes walk alone or with friends to the house where the excisions are to be performed without informing their parents. Then, the parents discover from others where their daughter is. If they were informed in time by their daughter herself, they are supposed to keep the news a secret for one day. They form a group with related neighbours, often relatives, who will make the payments on excision day and give the girl emotional and physical support.

The information that each neighbouring house must provide a man and a woman could not be generally confirmed; it even seems that most of the companions come from their own house. Although the girls’ answers about their companions are often not very precise (‘… some wives of my father…’), one can assume that each girl has about 5–10 companions during excision. However, for a single girl’s excision in Fumbisi, where I was allowed to be a spectator from a distance for a short time, about 20 female relatives had accompanied the girl. In one case in Kadema in 1988, of the 18 married women in a particular compound, nine accompanied an excision group, including a heavily pregnant woman. In addition, two younger men, who, from my observation, had little function in the excision, had joined the group. The yeri-nyono of the girls’ compound notified the chief of Kadema of the upcoming event before entering the excision house.

Excision in Fumbisi

The unmarried girls mentioned the following kinship names for the companions: Parents, mother, other wives of the father, brother, sister, wife of her brother, ‘uncle’, and ‘aunt’.

Only one girl mentioned a non-relative, namely her brother’s boyfriend. Suppose the girl is already married, as was the case for seven of the 15 girls interviewed. Only the mother-in-law and other residents from the husband’s house and neighbourhood may go to the excision, but no blood relatives of the girl who live in a different compound may do so.

The information of the Katiu circumciser that the parents of the girls come to her with a chicken a long time before the excision to announce their daughter’s excision cannot be generally confirmed because, as I said, it happens that the girl goes to the circumciser alone without the knowledge of her parents or at most with {204} friends who are also to be excised. I believe that this is not only intended to express the independence of her decision and the girl’s brave attitude, but I also see an essential separation (séparation in van Gennep’s sense [endnote 7]) of the girl from her previous social environment, into which she is gradually reintegrated after excision (agrégation). This separation holds even if her one-day stay in a strange compound, far away from all relatives, may only be a weak image of a period of seclusion.

When the girls have reportedly run to the house of the circumciser, this does not always refer to a house in the circumciser’s hometown. Instead, the circumciser, especially if he otherwise lives outside the Bulsa area, travels to a village, where he is welcomed as a guest in a compound. In Fumbisi-Baansa, for example, the circumciser from Bolgatanga had found accommodation with the section’s elder for several months. The girls also stay with this host from when they arrive until they are excised. Immediately after the relatives arrive the next morning, the girls are excised. The excision is preferably carried out in the cooler early-morning hours; parents and relatives who arrive too late may be persuaded to return the next morning or wait until then before the procedure occurs. Excisions usually occur after 7 a.m. but rarely after 11 a.m.

After the group of relatives’ arrival and the greeting, negotiations about the payment for the excision take place. Although informants repeatedly claim that the question of sexual virginity is only raised shortly before the excision, logically, the clarification must already have taken place here because the payments are based on the outcome of this question. Since the relatives often come from far away, this matter will sometimes have already been discussed at home because they must know what fowls to bring. Although onlookers can already tell from the animals brought whether the girl has already had sexual intercourse, the discussion with the circumciser usually occurs without many listeners. One informant says that the circumciser, the relatives and the {205} girl retire to an empty hut (dok) for this discussion.

Information varies about the type and amount of payment. There also seem to be local and temporal differences. I wanted to include the question about payment in the series of standard questions for the excised girls, but my male helpers advised against it. This question, they said, was insulting and would cause great embarrassment, as it was indirectly asking about their sexual virginity.

Here is the independently obtained information on payments to the circumciser (all names of the girls have been changed):

1. Payment for virgins:

Aguutalie, an excised woman from Kadema: one black chicken, one basket of millet cobs, and 40 pesewas.

Azuma, an excised student from Wiaga-Chiok: One black chicken and two baskets of millet.

Agaalie, a woman from Wiaga, married at the time of her excision in Sandema-Abilyeri: One basket of millet cobs and flour.

Leander (Wiaga-Badomsa): One black or brown chicken, one hoe, one basket of unground millet, and 1 cedi (formerly 20 pesewas).

G. Achaw (Sandema-Kalijiisa): One white chicken and other things (e.g. a hoe, tobacco)

R. Asekabta (Sandema-Abilyeri): One black chicken and one basket of unground millet.

Augustin Akanbe (Sandema-Balansa): One black chicken, one basket of millet, and 50–70 pesewas (formerly 2–4 pesewas).

Charles (Sandema-Balansa): One black chicken, one basket of millet, one hoe, and approx. 1 cedi.

Ali (Sandema-Balansa): One dark chicken and money {206}.

2. Payment for deflowered girls (in marriage or before):

Aguutalie: One black and one white chicken, one basket of millet, and 2 cedis.

Azuma: One white chicken and other things.

Leander: One black and one white chicken, one basket of unground millet, one unused calabash, One hoe, and 2 cedis (formerly 50 pesewas).

G. Achaw: One black chicken and other things.

R. Asekabta: One white chicken, one hoe, and 1 cedi.

Augustin Akanbe: One black and one white chicken and one basket of unground millet.

Charles: One black and one white chicken, one basket of millet, one hoe, and 2 cedis.

Ali: One white chicken and other things.

3. Payment if the girl has already given birth to a child in marriage or premaritally:

Aguutalie: Two black goats, one black and one white chicken, and one basket of millet.

Leander: One sheep, one black and one white chicken, one basket of unground millet, one hoe blade, and 2 cedis.

G. Achaw: One sheep and other things.

Charles: One sheep, one basket of millet, and 6 cedis {207}.

4. Payment if the girl is a reincarnated ancestor or ancestress:

Circumciser of Chana-Katiu: ‘one [additional] animal’ (goat, sheep or cattle).

One is inclined to believe Leander’s statements the most, especially since they coincide with several other statements. Not only has he participated in many excisions, but he also had his daughters excised, i.e., he had to make payments himself. In contrast, other male informants, as Christians and partly as strong opponents of excisions (G. Achaw), were more reminiscent of the cruelty and danger of the operation than financial matters, which never became acute for themselves.

One excised girl (Agaalie) significantly mentions only the basket of millet and flour in her tape report, but not the too-revealing chicken gift. Azuma from Wiaga-Chiok, who not only gave an account of her excision but also personally faced an interview, explains the fact that it is commonly believed that a deflowered girl pays for one white and one black chicken:

If you go to the ngadoa’s house and you have not slept with a man, he (the ngadoa) will excise you with a black fowl, but if you have slept with a man, he will excise you with a white fowl. If your parents ask you, you may be shy [about] telling the truth. So, they will take a black fowl and a white fowl to the house so that if any man has slept with you, they give the white fowl, but if no man slept with you, they give the black fowl.

Note that this explanation also applies if the parents learn that they must pay for a black and a white chicken, so the question must remain open for now. If we assume that the hoe, the calabash, tobacco, flour, money, and other gifts are only incidentals that can vary across time and location, the following scheme emerges for payment:

1. Virgins: One black chicken, one basket of millet, and other things.

2. Deflowered females: One white (and one black?) chicken, one basket of millet, and other things.

3. ‘Mothers’: One sheep (possibly two goats instead), one white and one black chicken, one basket of millet, and other things {208}.

Some girls mention that, together with the payment, the circumciser received white plant fibres, which were returned as ‘clothing’ for the girls shortly after their excision. The circumciser or his host usually provides a white millet stick. The circumciser can use the offered live animals for any purpose, not only for sacrifices.

If the girl is already married, all payments are made by her parents-in-law. In return, the girl’s parents later bring gifts of their choice to the in-laws’ house because it was the responsibility of the parents to have their daughter excised. Agaalie’s mother brought shea butter, salt, dawa-dawa, one guinea fowl and a mat to the husband’s house. However, it might also be other things (i.e. pito, flour, or millet cobs).

Before going to the excision tree, according to one informant (1988), cash was collected by an old woman from the group of visitors. I know nothing about the use of the money or the amount collected.

After the relatives or in-laws have paid for that day, the girls who have come in ordinary clothes change them for one-sided leaf aprons in front of the buttocks, and the whole group moves from the compound to a shade tree under which the operation is to be performed. It always occurs under a tree, never under a shaded canopy. At the excision in Fumbisi (January 1974), it was over 100 metres away, in Kadema (1988), about 30 metres away from the host compound. The type of tree is probably not significant; it is only supposed to provide shade. My informants have seen or experienced excisions under the following trees: acacia, mango tree, baobab, kapok and ninang (Sclerocarya birrea).

Near the tree, the circumciser or his assistant digs 1–2 (or more) holes about 30–40 cm deep. Azuma from Chiok reports that in Chuchuliga, all excisions of a year are performed in front of the same hole. When this is filled with blood, the blood is scooped into a second hole with a calabash. After this hole is also filled, it is covered with earth. According to other information, girls are only excised in front of the same hole in the ground if they come from the same lineage or section; otherwise, another hole is dug. In general, however, it can be said that blood and the cut-off body parts are not buried in the hole that takes these things immediately after the operation {209}. After these preparations, all the girls sit down in a row and wait. The circumciser asks them to lie down for a long time ‘as if they had died’.

In earlier times, there may often have been more than ten per day; the 15 informants give us the following numbers of participants (themselves included): 3, 3, 3, 4, 4, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, and 20, (4 informants give no information on this). In Fumbisi-Baansa, only three girls had been excised from 23 December 1973 to 8 January 1974, all on different days.

Sometimes, the girls are placed so that the youngest girl is excised first, but sometimes, the oldest girl – also the leader – is treated first. Other girls report that the order of their excision was arbitrary, while Aguutalie from Kadema claims that their fathers’ age or seniority determined the order of excision [endnote 8].

The silence of the girls waiting in a row is suddenly interrupted by a woman’s shrill cry (wuliing [endnote 9]), usually from the companion of the first-excised girl. Immediately, the girl jumps up, cuts her waist string and jumps high in the air a few times. Leander’s explanation that these leaps signify bravery and pride cannot fully satisfy, but no other explanations were offered. The girl sits down in front of the hole with her legs spread. If the hole is close enough to the tree, she can lean against it. Otherwise, she stretches her upper body back a little so that her hands can reach the ground for support [endnote 10]. Azuma reports that her ‘aunt’ from Chuchuliga sat with her back against hers so Azuma could lean against it. I (F. K.) saw (1988) that a girl put her arms around the neck of the circumciser.

If a girl shows resistance, she is held by two attendants on each side by her arms. Only if girls strongly resist are they tied to the tree. Shortly before excision, the question of the girl’s sexual integrity is usually raised again, even though the payments have already been made. Some informants attribute visionary powers to the circumciser: He may tell the girl to her face if, contrary to earlier statements, she has already had intercourse. G. Achaw recollected that one girl felt wrongly accused by a circumciser of having had sexual {210} contact with a boy. From her sitting position, the accused kicked the circumciser so that he fell lengthwise over onto his back (A similar case is described below for another excision). This insult to the circumciser had to be expiated by special payments from the attendants before the girl could be excised.

Another informant says that the circumciser touches the girl in the navel area. If she urinates, she has already had sexual intercourse. Leander’s description seems the most reliable to me: The circumciser smears dark charcoal on the girl’s navel and white ash around the vagina and then presses on the girl’s abdomen. If a secretion is emitted from the vagina, this is a sign that the girl has already had sexual intercourse.

The two assertions made above can be easily exposed as misunderstandings. In the first statement – that the circumciser arrives at his understanding from a supernatural point of view – the connection between the pressing of the abdomen and the maiden rehearsal has probably not been recognised, nor can a distant observer see the excretion that may leak. In the second case, the liquid excretion may be wrongly interpreted as urine. In the report about her excision, Felicia, from Wiaga-Sinyansa-Sichaasa, first noted that the circumciser can immediately see whether a girl has had intercourse. However, when asked, she gave a similar interpretation as Leander and described the secretion as ‘starch’, by which she means male semen.

Verification of sexual virginity by examination of the hymen seems unknown to the Bulsa or is not applied in this matter. In one case I know of, the male circumciser did not even recognise the existing pregnancy of the examined person.

After checking the girl’s virginity, the surrounding relatives and neighbours sing songs to encourage her. The singing continues almost uninterrupted until shortly before the group leaves. Of the songs sung, almost all informants cite the following as the most important {211}:

Weerik nan biak boa? Biaka ka dek biika.

Weerik nan biak boa? Kpajari yaa yogni [endnote 11]?

What does a leopard give birth to? It gives birth to its own child.

What does a leopard give birth to? To an aardvark or a civet cat?

The two lines of this song are repeated continuously. Azuma from Wiaga-Chiok reports that the below song was sung during her excision:

Gbangni, gbangni, gbangni biag biika, ate biika wman (= ngman?) chim boa?

The lion, lion, lion gives birth to a child, and what does this child become (again?)?

According to her, this song is only sung if the girl shows bravery. If she shows fear, the accompanying women can sing a mocking song:

Waaung gberi biak pok; yida la koa waaung.

A monkey has sexual intercourse with a dog’s wife; fear (or lust) kills a monkey.

Then the circumciser, who has rubbed the girl’s clitoris with a medicine sometime before, takes the clitoris out of the vagina with a curved needle (goatik pein) or with a fishhook and cuts it off with a knife [endnote 12] or with a razor blade. The circumciser of Chuchuliga has let his fingernails on his thumb and index finger grow to grasp the clitoris without an additional instrument.

The cutting activities under the tree lasted about 10 minutes, according to my observation in 1988.

Almost all the girls interviewed found the operation excruciatingly painful, and several informants admit to having cried out loud or – in some cases – tried to free themselves. However, expressions of pain or resistance are considered shameful; they are immediately met with threats and insults from relatives. On the tape recording by R. Schott (Excision in Fumbisi, December 1974), the women’s songs are interrupted twice by the screams of the two girls {212}. A girl from Sandema-Nyansa tells of her excision [endnote 13]:

At first, I was not afraid, but his first and second cuts were very painful. So, I pushed him down and wanted to run away, but the crowd held me and brought me back, and my mother-in-law abused me that I was a fearful girl. After this, I wanted to try my best but failed because the pain was too much. And as I pushed the man down, I (he?) was angry and was doing things so angrily. When he had finished cutting, I was very dizzy and could not stand at all or sit down.

When the narrator was examined by a neighbour’s wife the following morning, she received another unpleasant surprise:

When the dresser opened the sore, she said it was not well cut, so it must be cut again. She had to clean the blood only, and they had to call the man back to come and cut. At the second cut, I fainted. People thought I had died, and everybody was worried. Water was poured over me for about 20 minutes. I began to breathe, and they took me into the room.

Often, expressions of pain from the first girl being excised influence the fearful feelings of the other waiting candidates. For this reason, one probably likes to excise the oldest – and perhaps bravest – girl first so that the others are not frightened by expressions of pain. Alternatively, one may start with the weakest link in the chain – the youngest girl – so she cannot be utterly intimidated by expressions of pain from her predecessors. A girl from Sandema-Kalibisa reports:

I was the first to be excised. In fact, I could not help [stand/prevent?] it. The pain was very severe, very painful, in such a way that I could not lay down and allow myself to be cut. So, my brothers had to hold me, and I was crying. So, as the two other girls got to know it was painful, they started to run away, and their relatives had to chase them back {213}.

A partial passage in the English report of a student from Kadema-Chansa is reproduced in the following:

We got up early in the morning, and the man told us to get ready. He dug a hole and asked us whether we had (had) contact with a man or not. Only one girl (of four) had (had) contact with a man, and they asked her to pay.

First of all, they called upon one girl from Fumbisi to circumcise her, but that girl was afraid. So, they held her arms and legs, and she was weeping, and they told her she should stop weeping, but the excision man took a hook, and [I was] afraid, and I started weeping. My parents shouted at me. Then the man called me to come, so I lay down under (in front of) the hole, and I was weeping. So, my mother told [me] I should stop weeping. The excision man took a hook and held my excision [clitoris]. The visitors were singing and dancing, jumping and clapping their hands. I saw the excision [clitoris] jump and blood float and fill the hole…

Compared to these statements, which could be complemented by several more of the same kind, the following report by Agaalie [endnote 14], an enthusiastic advocate of excisions, does not sound entirely credible:

And she was excising me. And when I was excised, I did not feel any pain. When they were singing a song, I was enjoying it. And the people were surrounding me, and it was nice. When they were singing the songs, I also took part in singing. I was laughing all the time. It is not painful, not even a bit…

Usually, the girls are forbidden to peer into the ground hole after the operation. This prohibition is probably not a genuine taboo, but adults or those with more experience may want to spare them the sight. The student from Kadema-Chansa, for example, investigated the filled hole in the ground, as shown in the excerpt from her report. Azuma said that she was not allowed to look into the hole in the ground immediately after her excision, but when other girls were excised, she was allowed to if she wanted.

The excised girl is placed upright, and cold water is poured over her. Cold water is also poured directly over the wound {214}, which is reportedly very painful. Then, the excised person is given cold water to drink and, sometimes, kola nuts to eat. Supported by the neighbourly helpers, she is taken to her old place in the row of girls. If she has been notably courageous and stoic or tried to dance, then coins or banknotes are pressed on her wet forehead.

Agaalie reports that after her excision, the female circumciser from Chana-Katiu put millet water in her mouth and spat it out in four different directions [F.K.: This was a gaasika ritual, see 6.4.3 and 1st edition, pp. {222, 330f. and 389}]. The circumciser then instructed the excised girls to do the same. This [gaasika] ritual is also mentioned by Felicia (Wiaga-Sichaasa) at this point in the ritual sequence. R. Schott also witnessed it in December 1974 in Fumbisi, together with a calabash, spiralling the girl’s body (see p. 222). However, some informants deny that this ceremony was already performed under the excision tree.

According to my observation in 1988, this ritual took place about 10 metres from the excision tree. Before drinking from the calabash, it was moved around the girl’s body four times, and after the ritual, the girl’s body was showered with clear water (i.e. washed).

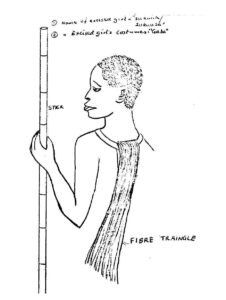

The girls always receive a stick from the circumciser made from a millet stalk called ngabiik kinkari [endnote 15], which must be white and cut from a millet field before the fire has charred the stalks. It does not support the girl while she makes her arduous journey home; the stick must not touch the ground and may only be carried in the right hand. Felicia recalls it as follows:

When the man said that we shouldn’t put the stalk on the ground, it meant wa kisi kama [it is forbidden, taboo]; you should hold the thing and bring forth a boy or girl.

Agaalie reports that before handing over the stick, the circumciser asked if she wanted a boy or a girl, and she replied, ‘Both’ [endnote 16]. This happened four times, then the circumciser threw the stick towards her, and she caught it. Aguutalie (Kadema) received the stick with the circumciser’s remark that this was now her child. Felicia was also given the stick, which she had to give back three times until sh was allowed to keep it the fourth time.

The girls, who were previously unclothed, dressed only in their traditional excision costumes (gaaba, gaba), which consist of white tufts of fibres (kanlieng, pl. kanliengsa) placed around {215} the neck with a cord so that the almost one-metre-long fibres lie on the back (cf. p. {216}). According to an isolated piece of information, these are supposed to symbolise a child tied on their back. The front part of the girls’ bodies and the abdomens thus remain unclothed. If the girls come through a village on their way home, they put a cloth (gatiak) around their hips. Otherwise, clothing is considered harmful because it hinders the free flow of blood. After a few days, when the wound has healed somewhat, the girl puts the cord of the gaaba around her hips so that the white fibres are laid from behind over the pubic parts to the front and the ends of the fibres can be tucked back under the waist string in the navel area.

This fibre apron is worn until it is dirty. Then, according to G. Achaw, it is replaced by a band about 20 cm wide, produced from the same type of fibres, which is tucked under the waist string at the front and back. Others (e.g., Aguutalie) say that after about 2–3 weeks, the old fibre garment is replaced by a new one of the same kind.

Before the individual groups leave the excision site, the circumciser may give the girls a piece of medicine made of charrred shea butter to be smeared later in their compounds on the neck, forehead, chest, between the big toe and the next toe, and between the thumb and index finger. Then, just before leaving the excision place, the circumciser shouts: ‘Baribee saratata’ [endnote 17]. All the girls run towards their compound at this call, followed by the adult group. Aguutalie (Kadema) had to run around the hole in the ground four times and Felicia was required to run once from the excision site to the circumciser’s compound and back before being allowed to go home. At the excision I observed in 1988, there was no call from the circumciser. The two girls only walked a short distance and returned to their starting point.

On the way home, war chants and other songs are sung. The girls are supposed to walk home without any help, but one girl from Sandema-Balansa reports that she was carried by three men when she could no longer walk. Azuma is proud that all four girls in her section walked independently from Chuchuliga to Wiaga [about 25 km] after excision. My offer to the excision group in Fumbisi to transport the girl and some older women across the more than 10 km distance to Wiasi {217} in my car was laughingly rejected without discussion. However, if a group passes a house where a relative lives on the way home, they can rest there. The excised girl may then be offered TZ or other food that does not fall under the food ban.

In the case I observed in 1988, the group left the excision house at 3.40 p.m. and arrived at their compound at 5.15 p.m., after walking about 6 km.

Leander’s drawing {216}

{217} NOTES ON THE DRAWING

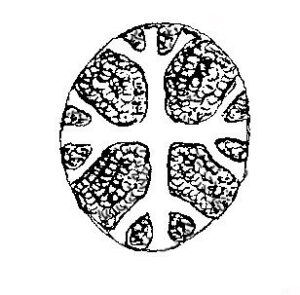

Leander Amoak made the drawing at my request. It was overlooked in the depiction that the excised girl should hold the millet stick in her right hand. The arrangement of the fibre tuft and the strings (in Leander’s drawing, one band or two strings?) deviates somewhat from a specimen in the collection of the museum ‘Forum der Völker’ in Werl. There, 15 individual strands of the fibre tuft are connected in 15 knots with two thin, twisted cords (miisa, sing. miik) (see sketch below).

Arrangement of the knots and strands in the Forum der Völker

Knudsen also mentions ‘loin wears’ and includes an illustration (p. 152). The upper interwoven part displays a third variation in the fibre connections; one depicted cotton loin wear is black.

After 1978, some changes, mainly concerning hygienic or medical measures, seem to have penetrated the excision procedure. For instance, modern disinfectants seem more frequently used. In addition, a Bulsa excision in Accra was performed inside a house, while hemostatic medication and local anaesthesia were used after the operation. Similarly, Knudsen’s informant says: ‘Thus, my friend and I bought our cotton wool, iodine, penicillin ointment and all that we would need…’

4. THE GIRL IN HER PARENTS’ AND PARENTS-IN-LAWS’ COMPOUNDS

4.1 Pobsika and food taboos

Before the excised girl enters the compound of her parents or husband, all the people she is prohibited from seeing must hide in their rooms (diina). The tabooed persons of the unmarried girl include her next younger brother or sister and her biological parents. If she is married, her husband is also forbidden from seeing her [endnote 18]. Other people may also fall under this taboo; for example, Azuma was not allowed to see her grandmother. According to other information, the medicine man (tiim-nyono) from the neighbourhood can be among the tabooed persons, as can all men who have had sexual intercourse with a widow before the funeral service of her deceased husband has been held. In addition, the excised girl is not allowed to see any tabooed people of a widow in the neighbourhood until the widow has blown ashes with these. One informant claims that the excised woman is barred from seeing her parents only if she is the firstborn. The visual taboo of seeing people from one’s house is lifted immediately after the girl’s arrival by blowing ashes (pobsika), a ritual that resembles the pobsika after birth.

Some food taboos have also to be kept immediately after excision: The girl is not allowed to eat food {219} that is called ‘black’ (sobluk) (see below) [endnote 19]. The following foods and drinks are usually referred to as black things:

Goat meat

Mudfish (Buli jum sobli, ‘black fish’)

Bean cakes made with a specific spotted small bean (turi)

Germinated millet or sorghum

Pito (daam, produced from germinated sorghum)

4.2 Treatment of the wound

On the day of excision, the girl must drink hot herbal water to stop blood flow and is only allowed to eat food heated to high temperatures. A woman experienced in treating wounds (fobro, pl. fobroba) is consulted. There are several such women in each section, so a woman from the close neighbourhood can usually be ordered for the following morning.

The treatment of the excision wound takes place in several phases. Four detailed reports will be given here in abbreviated form to sketch an illustration of the possible local variation.

The first report, from Azuma (Wiaga-Chiok) about the treatment of her wound:

a) She had to sit in the dalong for three days after excision without the wound being treated.

b) On the fourth day, a neighbour (fobro) came, opened the wound, and washed it with hot water in which medicine roots and leaves had previously been boiled.

c) Poosidi leaves [endnote 20] were placed on the wound. They burned like pepper. After each treatment, Azuma returned inside the house to avoid exposing the wound to the wind. She was not allowed to sit; she always had to lie down.

d) Titibi leaves (Combretum sp.) were put on the wound.

e) Some black bagta earth was applied to the wound.

f) When the wound had almost healed, Azuma took over her treatment; she washed the wound with hot water and put cham poli (leaves of young shea butter trees) on it {220}.

If Azuma’s personal wen-bogluk had objected to the excision, it would have had to be propitiated by a sacrifice immediately after Azuma had returned to her compound.

The second report from Aguutalie (Kadema) is as follows:

a) The wound was frequently washed out by the neighbour (fobro); cotton wool [endnote 21] and some black medicine (grated charcoal and shea butter?) were applied. This phase lasted four days.

b) A paste of ground poosidi leaves and cold water was pressed into the wound. This phase lasted approximately three weeks (until the wound became small).

c) Shea nut oil (kpaam) and cotton wool were applied for nearly a week.

d) When the wound had become bright, black mud (bagta) was fetched from the river. This could only be done when the moon was at its zenith. At the same time, rolls of blackberry bush (ngara vaata) leaves [endnote 22] were placed on the wound. The duration of the bagta treatment was 3–4 days. The ngara vaata treatment lasted a few days longer.

e) Aguutalie fetched and applied the shea butter tree leaves ‘to close the vagina’. After this, she was allowed to wear leaf clothing again. The first tuft of fibres had already been replaced by a similar one three weeks after the excision.

The third report, from Robert Asekabta, Sandema-Abilyeri, resident of Sandema-Suarinsa:

a) They collect leaves of the poosidi plant, roll them into a small roll between the two hands and press them until they become soft. This roll is placed on the wound.

b) The wound is treated with hot water in which titibi leaves (pl. titiba, Combretum glutinasum or Combretum ghasalense) have been boiled.

c) When the titibi leaves no longer yield any extract, they are replaced by leaves of the shea butter tree.

d) If these leaves no longer give off juice, they are replaced by blackberry bush leaves (ngaab, ngaarik).

The fourth report, from Leander Amoak, Wiaga-Sinyansa-Badomsa:

a) The charcoal shea butter medicine of the circumciser is applied in the first days.

b) The wound is treated thrice daily with cotton wool and hot water. This phase lasts one week (partly overlapping with phase A).

c) The wound is treated with poosidi leaves. The duration of this phase is approximately two weeks.

d) After the wound has almost healed, black earth (bagta) from the river is sifted and placed on the wound twice a day. This phase lasts four days.

e) Fresh leaves of young shea butter trees (cham poli) are mashed, formed into small rolls and placed on the wound.

Wound treatment in 1988: The woman who treated the wounds of the two girls could not tell me the medicine’s ingredients because the circumciser had given it to the group of visitors when already made.

The post-excision therapy also included guidance that the two girls constantly keep moving, such as by walking around the compound. They held their millet sticks in their right hands. They did not serve as walking aids, but sometimes, they would touch the ground. The two girls also fetched the water for their baths and cleaned the pots, which were sooty after heating the water.

The first wound treatment was performed by an older woman from a neighbouring compound, who also separated the vaginal walls in a painful procedure. Women from the girls’ compound completed the following daily ablutions and wound treatments (in the cattle yard). Here, too, the two girls sometimes contorted their faces in pain. The wound dresser also washed the two girls’ arms, legs, torso and hair each time, sometimes with soap. In the time between these treatments, however, the girls also laughed and sang a lot, sometimes until after 9 p.m.

The place of treatment is either the cattle yard (nangkpieng, pl. nangkpiensa) or the open space (pielim) at the compound entrance (according to Azuma at the tampoi). A deep hole is dug into which blood may flow and where the bloody cotton wool is thrown later. However, the plant leaves are not discarded but later burned, in their dried form, in the cattle yard. The girl(s) must then jump over the fire four times, according to R. Asekabta. G. Achaw and an excised girl from Kadema say that the white fibres are burned together with the leaves, while Leander and an excised girl from Wiaga-Sinyansa-Sichaasa claim that the white fibres are hung in a tree. These are not the white fibres the girl received on the day of excision because these were exchanged for new ones after 2–3 weeks, depending on the healing of the wound. According to Aguutalie, only after this change can excised girls leave the compound.

During the burning of the leaves and fibres, which I observed in the cattle yard on 16 December 16, 1988, the four jumps over the fire were not performed – instead, the two girls indicated a dance by slight movements.

4.3 Gaasika and ponika {221}

There is a consensus among my informants that, with the conclusion of the wound treatments, as indicated by the burning of the leaves, a ritual sequence called gaasika is performed. In the description of the gaasika, as it is performed at this point of the ritual sequence, the reports differ in some sub-actions, mainly through omissions or additions of rituals. Although the ritual procedure is very abbreviated in some parts of the Bulsa country, I attempt to provide as detailed a description as possible of the gaasika rites.

For the final feast day, the house’s women prepare food that the girl was previously denied permission to eat. These foods may include pito, a type of black fish (jum soblik); bean cakes; a small type of bean (tue); and goat meat. This previously tabooed food is eaten with TZ and a chicken or guinea fowl. The gaasika ceremony is performed in the open space (pielim) at the entrance to the compound – according to Azuma, at the rubbish heap (tampoi). The woman (fobro) who treated the wound officiates this rite for the excised girl. According to one piece of information, the food mentioned above is placed in four calabashes in front of the upright-standing girl. The woman (fobro) takes food into her mouth four times, spits it in four directions, as described above, and asks the girl to do the same. After that, the girl puts both hands on her head with their insides facing upwards, and the woman puts the food bowl on her hands, where it stays for some time while the woman whispers the following words to the girl:

Ma gaasi ka yabsa [endnote 23] gaasim daa biam gaasim-oa.

I perform the gaasika of the excised (the clitoris), not the gaasika of birth.

Then, the woman takes the bowl and turns it downward in four spirals around the girl’s body. At the girl’s lower abdomen (Felicia: ‘ … inside my legs …’), the bowl comes to rest again and is then further spiralled downwards, where it stays on her feet for some time again. After this ceremony, the girl is allowed to eat the previously forbidden food again; Azuma reported that she immediately disappeared into a room with the food pot to eat. According to another statement that has not yet been verified, some of this food will be offered to the household gods, after which the rest is distributed to everyone present, including the girl. The helper (fobro) takes any remaining food and at least one jug of pito back to her house as payment.

My informants are not sure whether the hair-shaving (ponika), which usually follows or, according to some informants, precedes the lifting of the food taboos is part of the gaasika rites. In any case, it is closely connected with them and is usually performed on the same day. A haircut without food taboos is a ‘shortened gaasika’, per Aguutalie from Kadema.

There seem to be local differences in the ritual sequences of gaasika subrites. However, almost all reports agree that gaasika and ponika occur after the wound treatment has been completed, i.e., after the burning of the leaves or after the last bagta treatment. Most informants and informants claim that a shortened gaasika with ponika is already performed as early as on the excision day. While hair-shaving always occurs in the compound, the gaasika can already be performed under the excision tree, as described above (p. 214).

Aguutalie from Kadema says there were three gaasika rituals during her excision, although the last one only consisted of a haircut.

1. The first gaasika with beans, goat meat and mudfish was performed in the compound on the day of excision immediately after the pobsika rites and the hair shaving, which was cut in the shape of a cross. This gaasika lifted the ban on eating the things mentioned above.

2. After burning the leaves – when the wound had almost healed – a second gaasika was performed with pito and bean cakes, which lifted the last two food prohibitions. However, it was not combined with a haircut.

3. After the wound had healed completely – when it no longer needed to be washed out with clear water, and the last fibrous clothing had been removed – Aguutalie’s head hair was once again shorn in a cross shape.

Head shave (top view, {224})

Aguutalie’s statement that her hair was already cut in a cross shape on the day of excision differs from almost all other reports, emphasising that the first shave is complete, with no hair remaining. In the second shave, two intersecting strips (naa–vuuk, pl. naa-vuuta, ‘cattle drift’) are cut into the short, regrown hair; in contrast to the otherwise similar shave after miscarriages, these cuts can also have side struts so that in the top view, a pattern emerges, as depicted here [endnote 24]. The shaving is performed by a person who knows how to cut hair, not necessarily the wound dresser.

If a Bulsa girl dies after excision, gaasika ceremonies will no longer be performed in the same year (It is unclear to which local area this statement refers).

After the last ceremonies, the girl is fully reintegrated into society, albeit with a different status and changed role expectations. As a marriageable woman, she goes to the market and is expected to work full-time again. If married, she is allowed to have sexual intercourse with her husband. If she is unmarried, premarital intercourse will not be resented as much as before excision.

As a sign of her new status – she is now fully marriageable – her clothes are changed. In the past, she had to wear leaves on the front and back – not only on the back, as was customary for little girls. This distinction in dress is hardly noticeable today, however, because young girls, whether excised or unexcised, consistently wear cloth dresses after the first signs of puberty.

A peculiar epilogue usually takes place a few months after the excision ceremonies. When the rainy season swells the rivers, the excised girl goes with her millet stick (ngabiik kinkari) to a river that does not dry up entirely in the dry season. She throws the stick into it, saying:

Nyiam ta biik a taam yoo!

The water carries the child away, oh woe!

After this, the girl fetches the stick again and throws it a second and third time, saying the same words each time. The fourth time, she lets the water carry the stick away before she goes home. This custom is performed by the excised girl alone. It does not need to be a specific day. Aguutalie reports that this epilogue is performed in Kadema after the excised girl has given birth to her first child. In the meantime, the stalk is kept under the thatched roof of a dok of her parents’ compound.

The visit of the excised girl’s mother in her daughter’s husband’s compound is part of the ritual. In one known case (1988), one woman’s mother’s visit occurred 12 days after excision, and the other woman’s mother visited her daughter after about one month.

At parting, mothers are given gifts like those given after the marriage of one of their daughters. For example, one mother received a busik basket filled with millet flour, a dead guinea fowl and a bottle of akpeteshi.

4.4 Rites of passage and excisions (2022)

Compared to other rites of passage, Bulsa excisions are low in religiosity. I cannot agree with the following assertions from Knudsen (p. 47) about the Bulsa excisions:

…the basic principle that guides rites of passage rituals among Ghanaian ethnic groups, including female circumcision or girls’ puberty rituals, is based on traditional belief in the Creator or in the Sky-God, who operates through gods and ancestors.

Visiting diviners before excision is an act that seems highly rare – and sometimes unfeasible, such as when girls run to a circumciser’s compound without notifying their parents. Again, my observations and information from my time among the Bulsa do not align with Knudsen’s assertion below (p. 47):

Thus, cosmological consultation through divination precedes all circumcision operations or puberty rites. This is true in all the three case studies [including Bulsa] I have described in this book.

In addition, sacrifices to the ancestors and other shrines are probably not a fundamental part of the excision ritual in any area. An informant from Sandema-Kalijiisa reports that the taboo food for the excised girls is partly offered to the shrines of the compound, while the rest is eaten by everyone else. Moreover, I have heard from several compounds that the ancestors there forbid excision. From Gbedema, I learnt that some circumcisers have a mobile bogluk to whom they sacrifice when complications arise during excision.

Undoubtedly, however, some of the rites and magical-based behaviours listed below are firmly integrated into the excision process.

4.4.1 Taboos

Concerning the food-based taboos for excised girls, various sources of information mention the following foods or drinks:

1. Millet beer: Cf. 1st edition p. {222}; information from Sandema-Kalijiisa

2. Jum soblik or jum goaling (Clarias lazera? catfish? mudfish, black fish): 1st edition: p. 222, Wiaga-Badomsa, Sandema-Kalijiisa

3. Pobla (bean cakes): 1st edition, p. {222}; Sandema-Kalijiisa

4. Tue (small beans): 1st edition, p. {222}; Wiaga-Badomsa, Sandema-Kalijiisa

5. Goat meat: 1st edition, p. {222}; Wiaga-Badomsa, Sandema-Kalijiisa

6. Buura (Neri, Egusi): Wiaga-Badomsa

7. Chicken meat: Sandema-Kalijiisa, guinea fowl meat is probably permitted

8. Chicken eggs [endnote 13]

9. Sheep meat

Eating the above foods, which are associated with dangta (dirt), could cause complications in healing excision wounds.

Additionally, Knudsen (1994: 166) mentions that the girls are not allowed to see a newborn baby for a while because ‘they had just lost theirs’.

4.4.2 Pobsika (ash blowing)

For married women, another sight taboo with their husbands is lifted when a pobsika ritual occurs in (or in front of) their residential compound immediately after their excision (per information from Badomsa).

4.4.3 Ponika (head shaving)

I was unable to gather any significant new information on this ritual after 1974. In one observed excision, the girls’ heads were shaved completely 25 days after excision, shortly before burning their leaves. I did not observe the head patterns described in the first edition (pp. {223–224}) in the form shown in the illustration above, nor did I obtain any new information about them. Possibly, it was replaced in more recent times by a simple head shave.

4.4.4 Gaasika

The performance of the gaasika was described above as a concluding ritual after the leaves have been burned (1st edition, pp. {221–224}). In Badomsa, it occurs only in the rainy season. However, according to my observations and through field notes by R. Schott, a gaasika is performed immediately after excision. In both cases, the calabash (with millet water or clear water?) was moved around the girls’ bodies four times until they took the liquid into their mouths and spat it out four times in different directions before swallowing it. My assumption expressed in the first edition (pp. {330–331}) that the gaasika ritual lifts a food taboo could not be generally confirmed by more recent information (after 1974). For the first gaasika immediately after excision, no such lifting was evident. In the second gaasika, after the wounds have healed and all activities have ceased, the forbidden food (together with water) is in the gaasika-calabash. It may afterwards be consumed again by the excised girls.

5. EXCISION AND BIRTH

Many authors dealing with problems of excision have observed a distinct connection between excision and greater sexual permissiveness or marriageability [endnote 26]. In this case, one must admit that this connection undoubtedly exists among the Bulsa. However, the relevant literature [endnote 27] says little about the relationship between excision and childbearing. Therefore, I remain unsure whether other ethnic groups are aware of the meaning of excision as an anticipated birth or whether ethnographers have less clearly recognised this interpretation. Among the Bulsa, many factors support such a meaning.

The following sub-rites and ideas about excision establish a connection to birth and its rites as commonly practised among the Bulsa:

1. The name for unexcised girls (kaliak, pl. kalaasa) also refers to (excised) women who have not yet given birth.

2. The girl’s parents must make higher payments to the circumciser if the girl has already given birth to a child.

3. Just before the excision, the attendants sing a song about the birth of a leopard, lion or monkey.

4. During excision, the girl has the same body position as a woman giving birth. Afterwards, she is also doused with water, as is done with a woman who has given birth.

5. The white fibre garment (gaba) worn by girls after excision was also worn in the past by women after the birth of a child.

6. The millet stalk given to the girl after excision is called her child (biik).

7. Before the stalk is handed over, the excised girl is asked whether she wants a boy or a girl {226}.

8. When the stalk is later thrown into a river, the girl laments, ‘Nyiam ta biik a taam, yoo!’ (‘The water carries the child away, oh woe!’).

9 A millet stalk also plays a role in birth rites. After giving birth, the woman must be ritually led out of the compound. She carries a millet stalk pulled from a thatched roof.

10. The millet stalk symbolises the clitoris as the ‘child born during excision’ who is later disposed of. Knudsen also received similar information from the Bulsa (p. 149: ‘…she grabbed the stick, which is also a symbol for a child’).

11. After excision, the girl must blow ashes (pobsi) in the compound with the same relatives as a woman after childbirth, namely, with her natural parents, the next younger sibling and possibly with her husband.

12. The excised girl must respect the sight taboos of a neighbouring woman in labour.

13. Like a woman giving birth, the excised girl should eat foods with plenty of katuak (spice produced from water filtered through millet ashes).

14. At the gaasika ceremony, the neighbour says, ‘I perform the gaasika of excision (or of the clitoris), not the gaasika of birth.’

15. After the gaasika rites, the girl wears the same hairstyle as a mother when her first child has died.

16. There is a belief that an excised girl will have an easy birth later.

17. An unexcised woman, like a woman who has not borne children, receives a man’s funeral ceremony. Knudsen’s Bulsa informant expresses herself thus: ‘So when I die, I shall be buried like a proper woman’. Perhaps this idea that an unexcised woman is an improper or inauthentic woman is contained in Knudsen’s statement (p. 45): ‘Technically, in some communities, an unexcised girl has no cultural status among her people’.

Some of the listed correspondences are not highly convincing. They may be based on coincidence (e.g. the leopard song) or were determined by the action itself and relate to the expediency of the actions involved (i.e. body position or cooling the body by pouring water over it) {227}.

However, the other correspondences are so extensive that they necessitate an explanation. Among the Bulsa, it is customary to refer to a girl’s clitoris as her child (biik), granting excision the functional value of birth. All subsequent actions up to the exposure of the ‘child’ in the river can be seen as a dramatic sequence of an anticipated birth. A notable step in this sequence is replacing the clitoris-child with the stick-child. The fundamental commonality between the clitoris and the stick is their phallic form. While the girl is given a (lifeless) substitute for the clitoris buried in a hole in the ground, the social environment performs rites on the girl that are performed after the death of a child (e.g. gaasika, cross hair shaving). However, the substitute child (i.e. the stick) remains in the compound.

Knudsen expresses this fact for the Bulsa and Frafra in this way (p. 171):

The major public ceremony… comes after six months, and their symbolic children have to be exchanged for real children. The millet stalks are then thrown into rivers while the girls mourn, hoping for real children later on.

When the girl detaches herself from the stalk, symbolizing the clitoris and the child, for the first time she does not endure ritual actions but becomes an independent actor without any co-actors. She plays her intended role in the dramatic process when she refers to the stick as her child. Notably, it would have been effortless to burn the combustible stick in the fire where the leaves were burned on the last gaasika day, thereby eliminating it. However, the character of the chosen way of disposing more resembles an exposure (‘The water carries the child away, oh woe!’), in which there is still a chance of survival for the ‘child’.

This study cannot and does not endeavour to offer a totalising, final explanation of the dramatic-ritual process described above. Such an effort would require more intensive individual investigations among neighbouring groups. Furthermore, it is certainly not my intention to try to enter into the previous scientific discussion [endnote 28] on the meaning of excisions, bearing new facts from a single ethnic group and retaking a stand for or against individual theories, since only a few statements were found about the connections between excision and birth shown here {228}.

Nevertheless, some of Sigmund Freud’s thoughts on the relationship between the penis or clitoris and the child seem pertinent to our topic. Freud believed that in a little girl, the desire for the penis would arise from the realisation of the clitoris’s inferiority. This desire is first narcissistic (i.e. the clitoris-as-penis substitute) and then transferred to the father’s penis.

Only later did the little girl’s libido turn to the father, and then she wishe[d] for a child instead of a penis [endnote 29].

According to Freud, women also see children as a penis substitute.

Es ist, als ob diese Frauen begriffen hätten – was als Motiv doch unmöglich gewesen sein kann – dass die Natur dem Weibe das Kind zum Ersatz für das andere gegeben hat, was sie ihm versagen mußte.

It is as if these women had understood – which as a motive could not possibly have been – that Nature had given [women] the child as a substitute for the other thing She had to deny [them] [endnote 30].

This last statement, in particular, is very reminiscent of the Bulsa ritual acts described above, wherein a girl who has just lost her clitoris, which the Bulsa also interprets as phallic, is given a phallic symbol (a millet stalk), and this symbol is called a child (biik). Freud finds a common linguistic symbol for the terms ‘penis’, ‘child’ and ‘female genitals’:

Es kann nicht gleichgültig sein, dass beide in der Symbolsprache des Traumes wie in der des täglichen Lebens durch ein gemeinsames Symbol ersetzt werden können. Das Kind heißt wie der Penis das ‘Kleine’. Es ist bekannt, dass die Symbolsprache sich oft über den Geschlechtsunterschied hinwegsetzt. Das ‘Kleine’, das ursprünglich das männliche Glied meinte, mag also sekundär zur Bezeichnung des weiblichen Genitales gelangt sein.

It cannot be indifferent that both child and penis can be replaced by a common symbol in the symbolic language of the dream as in that of daily life. The child, like the penis, is called the ‘little one’. It is well known that the symbolic language often transcends gender differences. The ‘little one’, which initially meant the male member, may thus have come secondarily to designate the female genital [endnote 32].

Similarly, in the Buli word biik, the root bi probably means small (cf. bilik = small). Even if I cannot follow all of S. Freud’s statements, it is quite conceivable that the Bulsa also unconsciously follow similar thoughts in the excision rites. The rites may help the girl {229} to cope mentally with the loss of the clitoris by immediately giving the excised girl a ‘child’ (biik) in the form of a stalk as a substitute; it is supposed to assure the girl about the purely female role she must play in social spheres from now on.

Addendum 2022: I found relatively little evidence in 1973–74 to support my interpretation that the clitoris also has the transferred meaning ‘child’ (biik) and that excision corresponds to an anticipated birth. However, as of 2022, Christiana Knudsen has reached similar conclusions in her detailed research among the Bulsa and other ethnic groups.

Without reference to the Bulsa [perhaps relevant for the whole of northern Ghana?], Knudsen writes (p. 198):

The clitoris, symbolically supposed to be a child, is analogous to a man’s ‘child’, the penis, and the precious masculine characteristics in a woman. When the clitoris is sacrificed, the feminine characteristics dominate…

After excision, the Bulsa girl receives a ‘substitute child’, the millet stalk (Knudsen, p. 148f.):

…After that, a woman handed a millet stick, about one metre long, to the circumciser, and she, in turn, threw it at the excised girl after she had asked a question and the girl had answered… Later on, I heard that she [the excised girl] made a wish for children while she grabbed the stick, which is also a symbol for a child.

Of the Frafra and Bulsa, Knudsen states (p. 171):

The major public ceremony… comes after six months, and their symbolic children have to be exchanged for real children. The millet stalks are then thrown into rivers while the girls mourn, hoping for real children later on.

According to Knudsen, other rites, such as those described in this chapter on birth, also occur among the Bulsa after excision. The ritual described by her on p. 151, in which the excised girl drinks millet water four times from a calabash and spits the potion out again in four different directions, corresponds to the gaasika ritual (see 4.3). An ash blowing (pobsika) is performed by the excised Bulsa girl, according to Knudsen (p. 153), with certain persons in the compound.

Finally, I wish to note that I am unsure to what extent Knudsen was influenced by my ideas from this book’s first edition. We communicated by letter before her book’s publication, and I sent her a copy of my book.

6. ATTITUDES OF EXCISED GIRLS TO EXCISION {239}

A sample of girls and women – possibly at different ages, in different positions (as schoolgirls or illiterates), and so on – would need to be interviewed to make valid statements about the attitudes of excised Bulsa girls. I believe such a study could only be conducted by a trained team, preferably of female Bulsa. In any case, such a study’s scope would go far beyond this work’s.

Nevertheless, I asked 15 excised schoolgirls and school graduates who were ready to give evidence the following question: ‘What do you think about your excision today?’ It is by no means my intention to evaluate their answers quantitatively. Still, it may be appropriate to give some examples of possible attitudes that may be useful for a later quantitative study.

6.1 Positive attitude towards excision

In addition to the report of a girl from Sandema-Kori from which we have already quoted (p. {202]), Agaalie’s comments are characteristic of a positive attitude towards excision. As already shown by a quotation above (p. {213}), there is a constant attempt to play down the negative sides (pain, danger, etc.). In this, she differs from other informants who, despite the admitted great pain they suffered, advocate excision and are proud that they are excised.

Agaalie, interrupted a few times by loud laughter, tells in the final part of her tape report {230}:

Since my mother is excised, I must also be excised. If I am not excised, I am a coward. As I am excised today, and I am sitting down like this, I am very happy. It is very nice. As my mother is excised, it looks I am now also a woman.

A girl from Sandema-Balansa-Bagubsa writes in her report:

I was very happy. I am still very happy that I was excised because it was [customary] from the old days that a girl should be excised.

Azuma (Wiaga-Chiok) makes the following comments in an oral interview:

Since I [got excised], if they say I should do it again, I will like it. Excision is helping people. If you are excised, and then you go to any place and die, or you do anything, they will always perform the funeral or whatever is wrong correctly. Now, if they talk of excision, I like it.

Another student from Wiaga-Chiok writes:

After my excision, I am very fat – (fatter) than (I was at) the time (when) I was not yet excised. I am very glad to say that (at) the time I was not yet excised, my friends who were excised laughed at me. And I was also very thin, but now I am very fat.

6.2 Indifferent attitude

Some girls interviewed today take an indifferent stance on their excision – or perhaps they do not want to show their genuine attitude. Once they have daughters of their own, these daughters should decide for themselves whether they want to be excised or not. The interviewed girls neither want to talk their daughters into excision nor advise them against it.

6.3 Rejection of excision

Two of the girls interviewed today strongly expressed a firm rejection of excision. Both had difficulties during their first childbirths, which they attribute to their excisions.

A girl from Sandema-Kalibisa had a negative attitude even before the excision {231}:

I was not happy to be excised, but my parents forced me. I lost two of my children, and I was told that it was because of the excision. So, I am not happy.

The following is the attitude of a girl from Sandema-Kandem:

I would not like to be excised again; after all, I heard that excision makes women become older in undue time because they have lost much blood, and when you give birth, you have to lose more blood. So, I do not think that if I were not excised, I would have liked to be excised again. I wish I had not done it.

Aguutalie, about 30 years old, says in a conversation that she was very proud at the time of her excision, but today people think differently. Her daughters should decide for themselves whether to undergo excision. Aguutalie herself would not like to be excised today.

7. EXCISION AND SCHOOL

In the school year 1972–1973, three of the 42 female pupils at Sandema Continuation Boarding School were excised. In the school year 1973–1974, there was only one girl. At St. Martin’s School (Wiaga), 11 out of 92 girls were excised in the 1972–1973 school year; in the following school year, with almost the same number of pupils (87), there were only four girls, three of whom were in the final class. When G. Achaw took his exams at Sandema Middle Boarding School in 1960, almost all the girls were excised by form three at the latest.

What reasons might motivate schoolgirls to avoid getting excised, especially in recent times? Talata, a school graduate, shares her attitude in the following report:

I would say that every girl at the age of excision should not agree with her parents or husband when she is asked to leave the school and be excised. I was asked to leave the school and be excised by my parents, and I refused. They did all that they could in order to get me out of the school and be excised but failed. At that time, I was in form four at the age of 15 years. In September 1972, when we were on holiday, I went to Tamale to spend my holidays there. That was to help me escape from my parents, who did not want me to be excised. And when the vacation was over, I came back to Sandema. I have (had?) a boyfriend – a teacher who taught me in form one. He wanted to marry me, and he has (had?) been visiting my parents with drinks and money. And my parents told him that they would excise me before [they] allowed me to marry him. But as I refused to do so, my boyfriend told me that he would not marry me – again, because I did not take the advice of my parents. It will be the same with him when he marries me. I will not take his advice either. So, I told him that I [would] not worry about it. You are not the only man in the world. If you did not marry me, I will get another husband. I disagreed (with) him, and [I, he?] went away [shamefully].

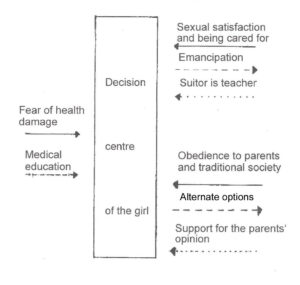

The psychological situation in which the informant had to decide can be illustrated in a diagram {233}.

{234} The influences indicated by a solid arrow (fear of health problems, sexual gratification and ‘being provided for’, obedience to parents and traditional society) may also help determine decisions not influenced by school or European culture. However, due to the influence of school, these motivations receive reinforcement or weakening (dotted lines). A fear of health problems is reinforced by school attendance. The motivation of some illiterate women that excision would make childbirth easier has been turned into its opposite: Childbirth can become more labourious and dangerous [endnote 35]. A way out is no longer offered by juju medicine or sacrificial acts but by the hospital. In an argument about this item with illiterate people, Talata will easily win because only she can give a medical explanation for her claim (blockage of the birth cavity by an excision wound). She received her knowledge, or at least her modern way of medical thinking, from the hygiene lessons at school.

Talata’s attitude against excision, acquired by medical reasons, must withstand two counterforces: the pressure of her parents and traditional society and her desire to marry her cherished boyfriend. In her resistance, school again comes to her rescue. Talata has no time for excision, as she must go to school every morning. Thus, her parents initially urge her to leave school, although it is unclear whether she should leave school for good or only for excision. The following holidays seem to bring a compromise solution (excision without the loss of tuition). But as with most other students, Talata also leaves Bulsaland during short holidays. As a student with English skills, with a larger circle of acquaintances outside the home village and with ‘better’ manners, it is easier for her to escape the parental sphere of influence.

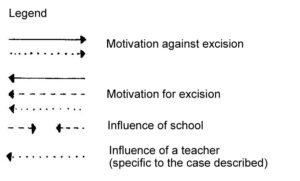

Talata had great difficulty renouncing marriage to a cherished man. Her defensive formulation (‘You are not the only man in the world. lf you don’t marry me, I will get another husband’) not only sounds very emancipated and {235} distinctly European but is also based on the fact that women have no difficulty finding a husband in a polygynous society. As an educated girl, Talata will also easily find another educated man to marry.

The motivations and counter-motivations discussed so far may apply to a generation of schoolgirls pushed into excision. However, our example is complicated because Talata’s suitor is a teacher – indeed, he is her former teacher, whom she was introduced to in middle school. This teacher, expected to hold ‘modern’ views on excision like most of his teaching peers, suddenly becomes an exponent of traditional society and allies himself with the girl’s parents when motivated to marry. However, as Talata’s account shows, even this alliance could not change her decision once she made it.

Although most male school-leavers make derogatory remarks about excision in conversations, some facts suggest that many still prefer an excised girl as a sexual partner [endnote 34]. When asked directly by an interlocutor whether he would prefer to marry an excised or unexcised girl, one often receives the answer that he (the informant) personally would not care; however, most students, he said, would prefer to marry an excised girl.