DEATH AND BURIAL

Descriptions and processed field notes

1. INTRODUCTION: ON RESEARCH INTO RITUALS OF DEATH

When I first began collecting material for my PhD thesis on the ‘Rites of Passage of the Bulsa’ in 1972–74, I ascertained that I should expect strong resistance and restrictions when researching death and burials. The funeral celebrations (Kumsa and Juka) – more accessible to strangers among these rites – initially seemed somewhat chaotic to me in their sequence of events; the meaning of individual rituals was often difficult to discern. A longer, multi-year residency would have been necessary for intensive, successful research. Therefore, I discontinued my in-depth exploration of this topic, and even in the publication of my PhD thesis (1978). The description and analysis of this pivotal rite of passage are absent.

In subsequent research visits to Bulsaland (in 1978, 1981, 1984, 1986, 1988–89, 1994, 1997, 2001, 2002–3, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2011, and 2012), other topics were the primary focus of my fieldwork, such as ancestor worship, divination, material culture, the Mungo cult, the earth cult, and the history of the Bulsa. Only after gaining trust and a great openness to information from all the inhabitants of a particular compound (Anyenangdu Yeri, Wiaga Badomsa), especially its head (yeri nyono), Anamogsi – through my repeated visits was I able to venture into the challenging exploration of the rituals and attitudes associated with the most painful crisis of life.

Death is an event that shocks close relatives of the deceased to such an extent that outside observers are often unwelcome. At first, when I asked a family I knew for permission to attend a burial, I either received a clear refusal or it was explained to me that the burial had already been conducted in the dark of night. It is thus unsurprising that, throughout my fieldwork among the Bulsa over 40 years, my access to the only three burials where I was able to observe all rituals completely and document via photographs was enabled in some way by Anamogsi, the compound head (yeri nyono), earth priest (teng-nyono) and elder (kpagi).

The burial of his granddaughter Akanchainfiik, who had died in infancy, was held in front of Anyenangdu Yeri. In Wiaga-Yisobsa, the burial of Anamogsi’s great-granddaughter Asiuklie was also made possible for me to witness by Anamogsi’s grandson, Yaw (my assistant and Asiuklie’s father). My attendance at the posthumous ‘burial’ (ngarika) of a man who had died abroad was only possible because Anamogsi, as an elder (kpagi) of the lineage segment of the relevant compound, was a respected co-organiser of the burial, meaning we did not need permission from the head of the deceased’s house.

In contrast to burials held in the immediate family circle, funeral celebrations (Kumsa and Juka), generally occurring only in the next dry season (or even years later), are much more of a public affair. The elders in the kusung-dok (the closed meeting room in front of the compound) usually do not refuse permission to a stranger to attend the ritual after he has greeted them with a bottle of akpeteshi (palm brandy). If reservations are expressed about a European’s participation, they usually come from younger participants with school education. I experienced such opposition twice in Wiaga, but it was fended off vehemently by the elders. In Wiaga-Mutuensa, the older men even let me come to them, bought me a drink, and emphasised that I was still very welcome at this celebration. In Wiaga-Chantiinsa, one son of the deceased who otherwise resided in southern Ghana raised objections to my participation, but the elders immediately rebuffed him.

In all other instances, I was met with a sympathetic welcome. In Wiaga-Guuta, after the welcome finished, the organiser (yeri nyono?) came to me and said that this was typically a smaller funeral celebration. However, because of my visit, it would be considered a large and significant one.

No general rules are set for photographing individual rituals. Most of the time, I asked during the greeting about which rituals and other activities would have photography desired or prohibited. The answer was usually the same: I could take pictures of everything, but pictures of the widows in their foliage costumes, especially when taking a bath, were not desired. This prohibition is likely less due to religious reasons than general human feelings of propriety and shame.

While visiting a funeral celebration in Gbedema, I was barred from observing all activities of the celebration by a young man with a good command of English, although I did not know whether this behaviour originated from him personally or if he had been instructed to do so by an official body. Although the former assumption was correct, I left the funeral without observing anything significant. Reports of this incident spread around Gbedema and caused great displeasure among some influential personalities about the young person’s behaviour. Even the chief sent his apologies to me.

Despite promises of free observation and photographic documentation, efforts to observe the celebration may occasionally be hampered by individuals or groups of people (e.g. the gravediggers). I noticed such obstructions several times during the two funeral celebrations documented in Sandema; I hardly experienced them in Wiaga. This may be because I am better known in Wiaga and have long been regarded as ‘Anamogsi Felika’ (Anamogsi’s white man). In Wiaga-Kalijiisa-Choabisa, I was taken to a neighbour’s house before the performance of the nang-foba rites (involving the killing of two cows). After photographing the mat burning, I was insulted by a drunken man. At the funeral celebration of Awuliimba (1989), the father of my (and Prof. Schott’s) long-time friend, Rev. James Agalic, we were promised unrestricted freedom of movement at the beginning. However, the gravediggers later forbade us from taking photos of the granary’s dressing, the donkey’s killing, and so on.

Even disregarding problems from some actors or participants, documenting a funeral celebration is difficult, mainly due to the various settings in which one may occur. In funerals for deceased women and men, most of the rites for the women occur behind the compound, while those for men do so in front of it. At this time, the older men in the kusung-dok can deliberate on important issues for which it is worth turning on the tape as other important rites are being prepared inside the compound. In these settings, working with only one camera and without at least one capable assistant who understands Buli well and knows how to handle a camera inevitably leads to imperfect results.

One problem in summarising all my documentation was that although I attended a relatively large number of funerals, I was only able to observe and document a few in their completeness over four days (see list of all funerals attended, Appendix No. 5.6). As already indicated above, my schedule is mainly responsible for this, according to which I often prioritised attending other events. In addition, I did not know some of the compounds visited very well beforehand, so I was not entirely familiar with the social and genealogical status of many people involved.

Surprisingly, the funeral celebration I did not attend was the best documented by interviews with the participants and photographs: The 1991 funeral of Anamogsi’s father, Anyenangdu, where my German friend Martin Striewisch was able to take photos and gather information without hindrance, and my co-worker Danlardy Leander (also of Wiaga-Badomsa) was able to record important rituals with his camera – even those performed at night. Perhaps more crucially, in my subsequent stays, I was able to gather any information I needed about these death rituals from my friend, Anamogsi, by analysing photographs from 1991.

2 DEATH

(Ku-yogsik or ku-palik, ‘fresh’ or ‘new death’)

2.1 The positive evaluation of earthly life

For the Bulsa people, the death of a close relation is an event that triggers horror and intense pain and confronts the individual with events and thoughts that were, before the event, mostly repressed from everyday life. Associations with death or funerals are avoided as much as possible in daily life or are taboo. For example, singing funeral dirges (kum yiila; singular kum yiili) or mixing beans (tue) and round beans (suma) before cooking together, as is done for a dish on the third day of the Kumsa funeral celebration, is forbidden outside funerary settings. People also like to use euphemistic-sounding phrases when discussing death and dying [endnote 1], such as:

O vuusi: He has breathed (his last breath).

Wa duag, wa ngmain yiti-a: He is lying; he does not get up (any more).

Wa noai ale niigi: His mouth is tired (fed up, sick).

Wa tong ka nang: He shot into his leg, meaning ‘He struggled before death’.

Wa taam ka nna diing: He has passed away peacefully.

Wa tog ka buketik: He kicked a bucket.

Fi liewa bo doku po: Your daughter is in the room (when announcing the death of a woman to relatives).

O basi teng zuk: He has left earth.

Wa sing ka kpilung: He descended into the realm of the dead.

Wa cheng ka ti koma tengka: He has gone to the land of our fathers. Wa diag o koba nisima: He shakes (shook) hands with his fathers (ancestors).

Wa siek ka ngaasa: He agrees with the ancestors.

In addition, for the death of a child, the typical word for ‘die’ (kpi) is not used, but ngmain (‘return’, i.e. the child returns in a rebirth).

Life in a ‘different world’ – the realm of the dead (kpilung) [endnote 2] – is similar to life on earth in many ways. The dead live in compounds with families and further kinship groups, but this different life is not necessarily enticing.

This notion is expressed, for example, in a Buli idiom that appears in various linguistic versions. An informant from Gbedema knows the following phrase:

Taa jo ka yaba teng zuk, kpilung ka ti miena teng.

We are enjoying the market on earth; the land of the dead is the village (or land) of us all.

The following version was provided in Wiaga:

Ti bo ka yaba, yabanga dan nueri ti te kuli.

We live in the market; when the market closes, we leave.

In S.A. Ekundayo (1977: 62), I found almost the same formulation with the same content in a Yoruba sentence name:

The world is a marketplace, but heaven is the home; we are strangers on earth; heaven is our home.

In all versions of this saying, earthly life is associated with a market. At the market (yaba), which occurs every three days, surplus agricultural products are sold, and goods not produced in the compound are bought. This marketplace is associated with a variety of pleasures and social contacts. These can start with the enjoyment of a bowl of pito (daam) in the company of friends and extend to the efforts of young people to find a suitable marriage partner (especially since such a search is excluded in one’s section or lineage among relatives).

If earthly life, when likened to the bustle of the market, is so appreciated by the Bulsa, it is unsurprising that the longing for death and the desire for a better life in the hereafter seem to have little place among the Bulsa. When the colourful market activities of earthly life end, the long period of ‘everyday life’ in the hereafter begins for them.

2.2 Causes of death

Any death can be classified as natural or unnatural, depending on the results of a divination session. People of advanced age who have been ailing for a long time usually die a natural death. In such cases, a natural death can be expressed by remarks that God (Naawen) has taken the deceased. For deceased younger people who were generally considered healthy and strong in life, one almost always seeks a supernatural cause in their immediate surroundings. Some examples of this scenario are given below.

(Information provided by Yaw Akumasi, fn 08,1a): When Anamogsi’s wife, Akumlie, fell ill, a diviner found out as the reason for her illness that her Christian son had thrown away her juik (skin). When Asuebisa retrieved it after an initial refusal, it was already too late, and Akumlie died.

Reporting on the death of his father, Danlardy Leander (fn 88,167b) said that his father slaughtered a black cock (at the tanggbain?) on the advice of an elder classificatory brother from another compound and uttered particular wishes which were not agreed to by the spirit. This led to his death. A diviner found that Leander would suffer great pain in the afterlife. The successor of the ‘elder brother’ wanted to slaughter a black cock again to undo his fatal advice, but persons from Leander’s family and others were afraid.

My first assistant, Godfrey Achaw (fn 55a), reports that ancestors kill very slowly, and teng and tanggbain do so very suddenly. If death comes gradually, the dead person receives a funeral celebration; if it comes suddenly, none. In the latter case, the death mat is burnt on the day of death, and the person is buried outside the house.

Murder is considered a very extraordinary and terrifying kind of death (fn 73,54a, G. Achaw). Although the execution of revenge is not (and was not) required before the usual burial of a murderer, the family of the murderer and the victim will since be considered enemies; in other words, they are not allowed to eat together or marry among each other. In one case, a man killed his runaway wife with an axe. The murderer had to undergo purification rituals but not make any payments. The traditional punishment for a murderer was that everyone shunned him, including his brothers, and he was not allowed to ask anyone for anything. Often, this led to his suicide. After his death, he is given an ordinary funeral celebration because otherwise, it would not be possible to hold celebrations for other members of his family who die later.

2.3 Kum-biok, the evil death

Certain external circumstances make someone’s death a kum-biok or ‘evil death’ (a synonym is kum-toak – ‘a bitter death’; a normal death is called kum-weeling).

Dying outside a compound without the presence of close relatives is considered shameful and is regarded as kum-biok. The types of death listed below are particularly associated with kum-biok (main informant Yaw Akumasi, fn 01,14b).

Opinions differ on whether a person who dies of a kum-biok can become an ancestor. While James Agalic from Sandema writes in his M.A. thesis that a person who has committed suicide, witchcraft or adultery, for example, also becomes an ancestor, E. Atuick (2020: 36) from Wiaga holds the following view: ‘…people who die through accidents, premature or sudden death, leprosy, witchcraft, etc. are never regarded as ancestors…’

2.3.1 Death during hunting accidents

In the past, kum-biok frequently occurred in fatal hunting accidents or war campaigns, and now also in fatal road accidents, after which no relative can hold the head of the dying person.

2.3.2 Death outside the compound

(case:) The death of a young man who wanted to spend the night in the kusung (a wall-less meeting room) in front of the compound and was surprised by death there is also given this derogatory name.

2.3.3 Death during pregnancy

The death of a pregnant woman is still considered reprehensible today. The embryo is removed from the dead woman by gravediggers by pressing the abdomen and then buried separately. The woman is buried against the outer wall of a guuk (an abandoned compound). She is always to blame for her and her embryo’s death because, allegedly, she did not want to keep the child (Yaw, fn 97,10a, Anamogsi, fn 02,16a).

2.3.4 Death of a leper

According to Danlardy Leander and Yaw, the death of a leper is also a kum-biok because it is a strict taboo to hold the head of a dying leper. Often, only his children are present at his death, and after his death, he is sprinkled with water using a leaf branch of the gaab tree [Diospyros mespiliformis]. Specialists are then consulted to deal with the death of someone who has died of leprosy (ning doma), and they perform rituals similar to those described below for death by lightning. The body of a leprous man with children is carried out of the compound through the main entrance, and that of a childless woman is over the back wall. If this height is too high to carry the body over, a piece can be knocked out (down to the ground). Lepers can only be buried by an old, experienced gravedigger (vayiak kpak).

The funeral celebration of a leper must not be held together with that of other deceased persons. In dark Buli [Buli soblik], a leper is called bolim (fire).

2.3.5 Dying from a curse

Curses can have evil consequences for the curse-giver and the cursed. At many tanggbana (earth shrines), a curse is considered an explicit taboo for all who sacrifice at that earth shrine. A curse is often not recognised as such by outsiders. The curser, for example, only says to another that he has to blame himself for the evil consequences of his actions. Or he leaves it up to a supernatural being at its shrine what should happen to the hostile person.

(Yaw, fn 11,8b): Anamogsi’s eldest son, As., did not want his son, Ak., to go to the south of Ghana. Before the trip, Anamogsi’s grandson had uttered a curse against his father, which neither of them had taken very seriously: ‘If I am going and if something happens to you, it is your own [fault]. If you do not mind, I am no longer your son’. Afterwards, As. visited his son in the south, and the latter bought his father a new bicycle and gave him money. But it was too late – a month after the visit, Ak died. A diviner confirmed that he had died because of the curse. As. then went south ‘to fetch the funeral’—he fetched some earth from Ak.’s grave in a cloth to be buried later in Bulsaland (see ngarika, Chapter 3,8). On his return, As. was waiting at the Alonggaab (Sichaasa-tanggbain). However, his father, Anamogsi, would not come to fetch him until the curse was withdrawn (he was also upset that As. had not given him notice of his journey to the south). Anyik (Atinang Yeri) and others persuaded Anamogsi to pick up his son. The earth was buried in the cattle yard. It has been doubted whether Ak.’s death was a kum-biok.

(Alice Bawa Ani, fn 81,1a): A woman of her house in Gbedema was doglie in Fumbisi and married there. Her husband neglected her and her child and did not attend funeral celebrations in Gbedema. When the woman became thinner and thinner from giving all the food to her child, her father ordered her to return home. When she disagreed, her father probably pronounced some curse on her deathbed and called her to him after his death, as a diviner discovered.

2.3.6 Suicide

Suicides in ancient society were mainly of the following three types (fn M53a):

1. Nag zuk, to bang one’s head against a hard wall or rock

2. Lu pein, to stab oneself with a poisoned arrow (it can also be a fishhook)

3. Bob miik, to hang oneself (this expression is also used when the manner of death is not known)

Self-chosen death (suicide) was likely rare in ancient society and was generally regarded as a shameful act that required atonement and neutralisation through extensive rituals. A large proportion of the suicide instances that I know of happened in the circle of the relatively more educated generation of the Bulsa – people who could not cope with the heightened tension between the old and new society or who had become fixed on their failures in school education or professional pursuits.

Relatively common are suicides by people who have been touched by a ghost (kok) and expect a soon-to-come and agonising death (examples in Chapter 6.2., Ghosts).

(Information from Margaret, 1978ff, fn M8a): One night a relative tried to hang himself from a dawa-dawa tree near the compound. When the rotten branch broke, he screamed for help. Apart from a broken leg, he was not seriously injured. The reason for his attempted suicide was that he wanted to join his ancestors. Margaret’s father said that one should not hinder a suicide, but he feared that he would be reproached. It was also rumoured that witches drove the relative to think of suicide.

In Gbedema, a man killed himself by injuring several parts of his body with poisoned fishhooks.

After trying to cut his throat with a blunt knife, he only injured himself and screamed for help.

2.3.7 The swollen body (nying fuusika) of the deceased as a sign of kum-biok

When a young woman (name and home known) died in Wiaga, her arms, legs, and abdomen were swollen. The swellings occurred after she left her husband who was supposed to have caused the swelling. More than 10 gravediggers were called for the burial. As is customary for women, the deceased was buried outside the traditional compound with the other women but a little away from them. The gravediggers and all those who had touched the deceased participated in the vaam-soka bath (see below), which was performed afterwards. Each bather gave a chicken and occasionally some millet flour to the head of the gravediggers.

2.3.8 Lightning

(Information from Yaw, fn 97,10a) A kum-biok by lightning (ngmaruk or ngmoruk) means that God (Naawen) has killed the person; therefore, his death mat must not be hung in the same room as those of previously deceased persons. After death, ritual specialists (ngmaruk-bisa) from Angmaruk Yeri (Wiaga-Yimonsa) come to the compound concerned. No one else is allowed to touch the dead person, and all inhabitants who were outside the compound at the time of death are not allowed to enter it until the Yimonsa men arrive. They come with water and certain herbs and, with the help of a broom, sprinkle (miisi) the dead person and his room and then walk once around the compound. All movable things they sprinkle belong to them afterwards, such as clothes, sandals, or a bench. They also sprinkle the corpse with their herbal water before burying the body. A person killed by lightning may be mourned only a little.

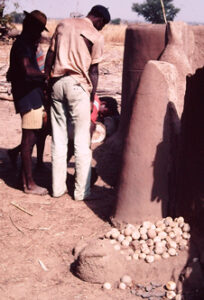

Stockpile of tintankori-stones in Asebkame Yeri

(Information corroborated by observations in Asebkame Yeri, Chiok, fn 88,121a) The compound owns a medicine that combats thunder and lightning. If a tree is struck by lightning, no one may touch it until the ngmaruk medicine has been sprinkled on it, and a person killed by lightning may not be buried without someone applying the medicine to the deceased. When the specialists go to an affected or strange house, they give its inhabitants a round stone (perhaps as part of the medicine?). Asebkame Yeri has a pile of round stones (tintankoa) to the right of the main entrance; it is a stockpile of stones collected from a river.

2.4 Occurrence of death

If a Bulsa man is afflicted with a serious illness that is suspected of leading to his death, the following measures may be taken:

2.4.1 A diviner (baano) should discover the illness’s spiritual origin. Has the sick individual sinned against the ancestors or other divine powers? Has he broken major taboos or omitted essential duties? Through appropriate sacrifices, they can try to change the course of events.

2.4.2 The medicine man (tebroa or tiim-nyono) is consulted for advice and therapeutic remedies. For example, he may prescribe using root extracts or charred plant parts or inhaling certain vapours or smoke. His prescriptions may contain religious–magical elements (e.g. procuring a root at a specific time of day at a given place). However, according to modern medical knowledge, some of his prescribed medicines may also have healing effects.

2.4.3 If the therapies above do not help, people may visit a clinic or hospital as a last resort. Today, this step is often combined with the healing practices mentioned above.

Meeting of a charismatic movement in Sandema

2.4.4 Healing through charismatic people: In recent decades, some charismatic Christian movements have promised the ability to heal almost all diseases [endnote 3]. The leaders and their helpers pray for the patient, give behavioural instructions, and administer healing water. Such faith healers are visited by followers of almost all Christian denominations and, to a large extent, by members of the traditional religion.

2.4.5 If all remedies and therapies prove ineffective while the condition of a terminally ill person continues to deteriorate, arrangements are made for their expected death. These include that a dying person living in a more modern house in the centre of a village is taken by family members to the individual’s ancestral paternal compound at night. In anticipation of their death, the dying often advocate for this transport themselves. Married women, for example, want to die in their husband’s house (not in their parents’ house).

2.4.6 In a chosen room (dok; often, it is the dayiik) of the traditional compound, the dead person is laid on a mat, which will later play a significant role as the person’s death mat. Some older women are constantly near the corpse. They try to comfort him verbally (saying, e.g. Naawen te fu nyingyogsa, i.e. ‘God give you health’).

(Margaret, fn M60a) They may sprinkle water on a sick person’s body or administer more medicine to relieve pain. Most importantly, they must hold his head and upper body up so the sick individual is almost sitting.

(Margaret 1978ff, fn M60a): When an old man in Gbedema died, many visitors said, ‘Naawen te fu nyingyogsa’. In response, the dying man said, ‘Aba, Naawen yeng ka le la’. (‘That’s enough! This is the same God!’ or ‘There is only one God’). He continued, ‘Wa nya Ama. Fumbisi abe wa jam nya mi Gbedem ale ku baasa nying la’ (‘He should see [the dying] Ama in Fumbisi and then come and see me in Gbedema so that I will feel better’), meaning ‘God is not everywhere and cannot help Ama and him at the same time’.

(Yaw, fn 02,36a) In Wiaga-Chiok, when a man of about 70 was dying, his juik skin, a visible object of a spirit connected to the mongoose [endnote 4], was placed around his neck. By doing this, he said goodbye to a spirit that was exclusively connected to himself. Only certain people were allowed to remove it after his death and display it outside on a stick until it rotted [endnote 5].

2.4.7 Determination of death: If a person’s death is noticed due to, for example, the cessation of breathing, the death can be checked by other measures. These include listening to the heartbeat or holding a mirror in front of the dead person’s open mouth, perhaps to perceive minute respiratory currents.

2.5 Kuub darika, the announcement of death

After someone’s death, their close relatives are filled with deep pain. However, those mourning are not allowed to show this to the outside world until after the official announcement (kuub darika) of the death and the digging of the grave has begun.

2.5.1 Reasons for postponement

While the kuub darika is usually performed immediately after death, there are reasons for postponing it, as some examples will show:

– A kuub darika could not be performed in Badomsa because a wife of the deceased was still staying in Accra (fn 2011,8a).

– (fn 2011,8a) After an old man’s death, it was suspected that one of his wives had committed unpunished adultery. This woman, however, refused to undergo the kabong-fobka ritual, where a white chicken – which incurs the guilt of the accused – is brushed over the human body and then killed by beating it on the ground [endnote 6]; the kabong-fobka ritual, performed properly, allows a diviner to determine that the death can be announced.

– (fn 94,17b) When an old diviner (baano) and compound head (yeri nyono) died in 1994, his death was not allowed to be announced because he had skipped the kuub darika after his father’s death. He was immediately buried ‘like a toddler without any subsequent siblings’, including no mourning. Even in 2007, his death’s announcement had not yet happened. If subsequent rites and amends do not clarify the matter, all the diviner’s children will be buried without the kuub darika ritual.

– (Information from Danlardy Leander) Reasons for postponing the kuub darika include that a severe illness afflicts many in the compound or that there is a major dispute. If another person dies shortly after the death, the second death cannot be announced until the kuub darika of the first person has been completed.

2.5.2 Performance of the kuub darika

The announcement often begins with initial information given to the nearest relatives living outside their compound (ko-bisa; literally, ‘children of one father’) in the order of seniority. They are also invited to the mourning compound [endnote 7]. After the ko-bisa, more distant relatives are informed, but they are only told that NN has died; further details of the death are not provided.

Sons-in-law of the deceased usually receive the death news through their san-yigma. This man is related to both the son-in-law and the father-in-law (i.e. matrilineally) and played an intermediary role in bringing about the marriage (cf. Kröger 1978: 274–75).

An informant of mine, Ayomo (fn 81,47b), was the sanyigmo of Atanla’s wife (Abapik Yeri), who came from Sandema-Abilyeri, like Ayomo’s mother. When Atanla’s wife died, Ayomo was tasked with providing a hoe and a chicken as gifts to announce her death at her parents’ house in Abilyeri. Ayomo also played a significant role in her funeral celebration.

Invitations to a funeral or a mourning visit can also be declined. After Yaw and I brought the body of Yaw’s sister to Apok Yeri, her traditional parental home, we were asked to visit far-flung compounds of relatives on our bicycles as part of the official announcement (kuub darika) and issue invitations for the burial. An old head of a compound, Yaw’s grandfather (MF) – who would have liked to conduct the funeral – declined the invitation because Yaw and his mother had not accepted his invitation to his father’s death rituals.

(fn 94,91a) Upon the death of Danlardy’s stepmother, Maami, her family first informed the ko-bisa and the other compounds of Danlardy’s lineage (Adiok Yeri, Abakiak, etc.). They all came to the compound of Danlardy’s father (Leander) and informed the stepmother’s san-yigma. He then informed the chief’s house (the deceased’s parental compound), though its inhabitants had long since heard of the woman’s death [endnote 8]. (fn 01,8a) Shortly thereafter, people from the chief’s compound came to Asik Yeri (Badomsa) to inquire about the ‘weariness’ (jianta) of the residents [endnote 9]. They received drinks there; Danlardy and his classificatory siblings – Michael, Tenni, Francis, Oldman, Ayomo, and Atongka – and his mothers and others also gave money. After about one week, some residents of Asik Yeri (including Ayomo, Atongka, Kenkenni, the mothers and others) returned to the chief’s compound. They were given millet water and alcoholic drinks; old men and others also gave money, though they would not have given it if they had not received money in Asik Yeri. They gifted so much akpeteshi that Danlardy’s relatives could not drink it all and took half a bottle home. Danlardy calls this exchange of gifts ‘siinika’ (cf. chapter 4.2.4.2.: distribution of gifts at the Kumsa funeral celebration).

(Yaw, fn 01,11b): When a wife dies in her parental compound (e.g. during a visit), her husband or son sends a nakogla bangle along with tobacco, kola nuts, and alcoholic beverages for a libation to her parental compound. The in-laws can keep the bangle if the funeral celebration is held at the husband’s compound. This practice is still carried out today.

2.6 Notification of the earth priest (teng-nyono)

Notifying the earth priest (teng-nyono) of the death is often necessary. In the interviews with the 41 earth priests of Wiaga, I ensured to ask whether the bereaved must seek permission to bury a deceased person. The earth priests of, for example, Guuta, Zuedema, Bachinsa, Kubelinsa, Longsa, Dogbilinsa, Yisobsa-Yipaala, Bandem and Farinsa must give this permission. The earth priests from other sections said they only required information about the death. If the deceased was a witch (sakpak) [endnote 10] or was killed by the tanggbain of their earth priest, the relatives have to provide the tanggbain with a ‘mammal’ (dung), which must be a bovine in many cases (e.g. the tanggbana of Bachinsa, Kubelinsa, and Bandem). In general terms, Adama (from Chiok) explained that a cow must be given to a teng-nyono if the deceased was killed by his tanggbain.

If earth priests must give permission for the burial, it must also be sought before a Kumsa and Juka funeral celebration. Some earth priests stated (without my asking) that they would attend the funeral if possible.

2.7 Mourning and mourning visits

Before the kuub darika and the grave digging begin, no mourning visits or expressions of grief may occur. Even close relatives must withhold their grief until then. For safety, one inhabitant of the compound is sometimes sent to the compound’s main access road to prevent loud lamentations from arriving guests.

After the death announcement, expressions of mourning by the compound’s inhabitants begin, and relatives or friends from other villages visit the compound for this purpose (Achaw, fn 73,45). Even if daughters are married in faraway compounds within Bulsaland, they must come on this specific day. Today, this is made possible by bicycle or car travel. Before a daughter of the dead leaves her husband’s house, a long fibre rope is tied around her left arm. She is held by it if she wants to run too fast to her deceased father’s house; the rope is also said to prevent the daughter from committing suicide. More distant relatives can mourn on their way but only utter loud cries when they are a few hundred metres from the house. When a father dies, a son must always be accompanied by someone from his age group (even when he goes to the toilet) ‘to prevent a suicide’.

The extent to which a person is personally affected by the death does not influence the kind and course of the mourning rites. Mourners arriving from outside might not show any signs of distress; they perhaps even joke among themselves 50 metres from the compound. As they approach the compound, however, they begin to cry loudly and utter ‘Waa-soi’ or other cries of grief in tears.

A mourning man is supported (chogsi) by another man (chogsoroa or yigdoa) as he walks, and a mourning woman by at least two other women – sometimes by additional female companions (Inf. Yaw, fn 2006,35a).

Mourning in Wiaga-Bachinsa

Female mourning groups proceed all the way to the dalong with the laid-out dead person (later, his death mat); conversely, men usually only walk a few steps through the main entrance (nansiung) into the cattle yard (nangkpieng) and from there, back to the rubbish heap (tampoi) in front of the compound. Such a funeral procession may be performed several times. At the tampoi, a woman or child hands the mourners a calabash of clear water for washing their faces. Afterwards, when the mourning ritual is over, people may laugh again.

There is no prescribed time limit for mourning visits. Mourners may still arrive many years after a death. Non-relative friends of the deceased should come after the burial because they might die should they see the body – they are in constant danger of being taken into the afterlife by their dead friend. After the death of my first helper and friend, Leander Amoak, and after the death of Anamogsi, my friend and chief informant, my Bulsa informants even feared danger to me if I came to see their grave years later [which happened anyway].

(fn 02/03,32b, Information from Yaw) After the death of a young man, one of his former friends said that she wanted to die with him. Immediately a ritual of ‘undoing’ (piirika) had to be performed. The young woman thereby said: ‘Mi le biisa di la, di la le nna, ate n pursi bas’ (literally: ‘What I have said, it is this, that I spit it out’. Freely translated, it means: ‘I hereby take back my statement’). Afterwards, the woman was rubbed with ashes from the hearth or tampoi so that the dead person would not be able to recognise her.

Mourning visits by distant relatives or Europeans have a different character, especially when they occur after the burial rites have been completed. In English, the Bulsa use ‘sympathising’ (Buli: yika) rather than ‘mourning’ (kumsa) to describe such visits.

In 1981 (fn 81,14b), Leander Amoak and I visited Azubak Yeri in Bachinsa to mourn. When we approached the compound, my companion suddenly began crying loudly and shouting (‘waa-soi’ or ‘yaa-soi’). A small boy came out of the compound to support him. Leander went to the courtyard where the mat was already hung up, then to the ash heap (tampoi), back to the mat, and finally to the kusung. A small boy brought him a large calabash bowl with clear water for washing his eyes. After that, they were allowed to laugh again.

(Information from Yaw, fn 06,35a): My co-worker Yaw was in southern Ghana when the compound head and his (classificatory) father-in-law, Aluesa, died. Therefore, a delegation from Yaw’s Wiaga compound, Apok Yeri, went to the home of the late Aluesa in Wiaga-Sichaasa without him. Yaw did not need to make up the visit, but even if the group from Apok Yeri had not gone to Sichaasa, he would not have done so as a Christian. Later, Yaw’s wife, Tenni, went with the Ama (the senior wife of the compound) and other women from Apok Yeri to Sichaasa to the Amadok (the first wife’s court) to mourn. There, she also greeted the other women of Anduesa Yeri and its neighbouring compounds, giving them kola nuts and drinks for their services to her classificatory father. She then went to the men in the kusung and gave them alcoholic drinks for enduring the cold (ngoota) during the burial. Several shots were fired to indicate to the neighbours that a child of the dead man had come. If Tenni had not paid a funeral visit, she would not have been allowed to mourn after the death of her biological father.

Mourning experience of the author in Anyenangdu Yeri:

A European who was friends with deceased Bulsa is not expected to perform the Bulsa mourning rites in detail and start crying loudly before he reaches the compound. However, a funeral visit is necessary for him to maintain his friendship with the compound. The English word ‘sympathising’ is often used for this mourning visit.

After my 2005 stay at Anyenangdu Yeri, its headman (yeri nyono), Anamogsi passed away. When I returned to the compound in 2006, I was expected to make some official expressions of mourning (fn 2006,1a; fn 2011,1a).

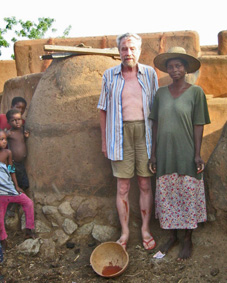

The author painted with red earth

First, I visited the men in the kusung. Although I had seen and greeted them before, an official greeting still had to occur. Before drinking, I and everyone present offered a libation of my donated akpeteshi (palm brandy) by pouring some brandy on the ground. After this, I went with my helper, Yaw, to the courtyard of the deceased’s eldest wife. Here, too, we and others drank from the alcoholic beverage we had brought with us. This time, however, the libations were omitted. I was only allowed to see the grave after completing this sequence of events [endnote 11].

A similar process of ‘sympathising’ had already happened in 2005, after my long-time cook Agoalie – one of Anamogsi’s wives – had died before I arrived in Ghana. One day after the mourning rites, as described above for Anamogsi, I was taken to the compound’s cattle yard. At the entrance to Agoalie’s living quarters stood Ajadoklie, a daughter-in-law of Anamogsi. She had played the impersonator (che-lie) role at Agoalie’s funeral and was now wearing Agoalie’s straw hat. She held a calabash with red daluk earth mixed in water in her hand. I was painted red by her on the following parts of my body:

1. Vertical lines on both shins,

2. Strokes on the forearms,

3. And a horizontal line on my forehead.

Only after the mourning ritual I was allowed to see Anamogsi’s grave.

Ajadoklie explained that had I been able to attend the funeral, I would have been painted the same way. I presented a monetary gift to Ajadoklie to compensate her for her services as an impersonator of Agoalie.

2.8 Mat gifts at the burial visits and later

Immediately following the death of a person up to the Juka funeral service, tiak sleeping mats are more or less officially given to the house in mourning by married-out daughters and sons-in-law. The somewhat confusing information about mat gifts to the house of mourning shall be compiled here for clarity.

2.8.1 Gifts at funeral visits before the death celebrations

(Information from Danlardy, fn 88,305a) Before the funeral of a married woman, the brothers of the dead – men from her birth section – come to the house of mourning (i.e. her husband’s section) with a mat (tiak). This mat initially remains in the cattle yard; the death mat remains in the dabiak (inner courtyard). Later, the mat from the birth section is placed in the bedroom of the dead with a new calabash. When daughters of the dead come to their parents’ house, they are supposed to sleep on it and drink from the calabash. However, this is no longer done by everyone today.

According to other information, the death mat is exchanged for the donated mat later, but before the ta-pili yika ritual, as the former mat becomes dangerous due to contact with the dead and the smell of corpses (piisim). One will destroy the original death mat later by, for example, throwing it into a river.

(From a letter of Danlardy, fn 97,63a): The mat on which the dead passed away can be wrapped around a donated mat – the lie kuub puusa mat [‘the daughter greeting death‘ mat] – and then hung in the kpilima dok. At the Kumsa funeral, the lie kuub puusa mat is burnt along with the death mat.

Observation in Wiaga-Goansa (fn 97,47a): In the centre of Wiaga (near Leander’s residence), I observed a group with a mat from Wiaga-Farinsa (Akanko Yeri), the childhood home of Leander’s wife, Atoalinpok. Their musical accompaniment consisted of two gungong drums, one gori drum, and three flutes (wiisa). They had only made their funeral visit to Asik Yeri now, four years after Atoalinpok’s death, because there had been problems at their compound. They performed a small round dance at a Goansa tree.

2.8.2 Gifts of mats during funeral celebrations

(fn 88,272a, fn 94,89a) According to Danlardy Leander, at a funeral of men or women, the wives of the sons of the deceased each provide a mat – or, if they cannot, a calabash – to be placed at the bui. The mats are distributed on gbanta-dai to the che-lieba (women who perform activities as impersonators, for example). If there are mats left over, the physically present daughters of the dead also receive one mat each. This statement by Danlardy corresponds with observations at a funeral in Wiaga-Mutuensa (fn 88,272). In the cattle yard at the granary, eight mats made by the wife and daughters of the deceased immediately after the burial were stored. These were given away after the funeral celebration.

According to custom, at a Kumsa funeral in Guuta, the mats of deceased persons whose funeral celebrations were included in the main funeral celebration were fetched from the neighbouring Awusumkong Yeri. Gravediggers carried these mats. Five other mats were fetched from Awusumkong Yeri at the same time; however, these were not funerary mats but gift mats, so they were carried by women (for further examples, see Chapter 4.2.1.12: Funerary mats from neighbouring compounds).

3. BURIALS

3.1 Activities before the burial

(For more details on such activities, see Chapter 3.4.1, Burial in Yisobsa).

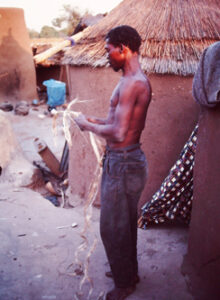

After a death in a family, and, if he is not present, the yeri nyono is informed first. He will immediately look for suitable gravediggers (vayaasa, singular vayiak), who, after examining the deceased, will confirm the death again and then lay the dead person on the death mat (tiak) in the dalong (kpilima dok, ancestral room). If the death occurred outside the compound, a used death mat must still be obtained for the laying out.

Shortly before his burial, a dead man is washed. He is dressed in his best clothes – specifically, a cap and a traditional smock, usually only worn at festivals. European clothing and head coverings for women are not allowed; red garments, red patterns, or stripes in clothes are also taboo.

She Bae [aka Dorisday] Abiak Ambagwie, a participant in the discussions of the Buluk Kaniak Facebook group, could not attend her father’s burial, but she later saw the video recording of this event. She reported on Facebook about her father’s clothes and her impressions (27 January 2019)

… I think every house [has its own way] how they bury their dead because in my [house] they bury [you] naked. They only dress you with the golung [triangle cloth], and when they get to the graveyard, they remove it. I am saying this because when my father died, I was not around, but when I got to the house, they took a video of him how they laid him, and it was [on?] one side, then they used his hands to close his ears. I was angry that it was around March. The sun and the ground was [were] very hot. At least they shouldn’t have removed the smock, and they explained that we don’t bury with dresses, and I don’t know whether that is how everybody does.

3.2 Burial site

A grave’s location depends on the deceased’s kinship status and gender. There seem to be minor differences between the different Bulsa villages. The following list refers mainly to Wiaga.

3.2.1 Important old men, often also heads of the compound, and some women – though more rarely – are buried in an inhabited courtyard. In one case, the mother of a yeri nyono’s younger son was buried in the courtyard of her son because she was the wife of the compound’s founder. Heads of compounds are usually buried in the courtyard of the first wife (Amadok) – that is, near their ancestral room (kpilima dok).

In Wiaga-Sinyangsa, a yeri nyono’s burial outside the compound rather than in the main courtyard was the subject of heated debate for a sustained period. After his death, his eldest son had him buried outside the compound. The exact reasons for this are unknown to me, but the second-eldest son (my informant) called this act a form of villainy. Due to this burial, the eldest son and, later, my informant, would also have to be buried outside the compound. A few decades later, people were still discussing whether the deceased should not be transferred to the compound’s Amadok and reburied there.

3.2.2 Young, childless men and women (perhaps only of compound’s lineage) are buried in the cattle yard (nangkpieng [endnote 13]). Strangers from another section (e.g. wives) who die in a compound of their residential sections are either buried outside the compound or in the cattle yard, close to their residential quarters. I know of a case like this from Wiaga-Badomsa (fn 88,231a).

According to Godfrey Achaw (fn 73,46), in Sandema, men are buried in the cattle yard, while women are buried outside the compound on the path leading to their village. The reasoning behind this choice of burial site is that men belong to the house, and women should be able to walk quickly to their village.

According to Margaret Arnheim, in Akanwari Yeri (Gbedema-Gbinaansa), the dead are buried in the cattle yard or in a dabiak (courtyard). In the cattle yard, a stone is placed over the grave if cattle have broken the grave bowl. The burial of adults outside the compound is atypical (fn M1978, 52b).

3.2.3 Outside the compound – not far from the enclosing wall (parik) – is where women (wives from another lineage and sometimes unmarried women of their lineage) are primarily buried. Some compounds ensure that their grave is on a footpath leading to the deceased woman’s parental home.

Margaret Arnheim reports the highly unusual case of a young boy buried outside the compound wall in Gbedema (fn M46b). When the informant was at Sandema Boarding School (Form 1 or Form 2), a boy of about the same age died in Gbedema. After he had fallen ill, they wanted to take him to the clinic in Wiaga, but he had an accident on the way. When he died in the compound, a diviner stated that the ancestors did not want him to visit a clinic. Since his parents were strict Catholics, they had catechists say prayers at the grave. His grave is on one side of the compound; behind it is an elongated heap with many medicine pots, skull bones, and other offerings associated in some way with the ancestors. No ancestor of this family was buried at the compound because they had died in southern Ghana. Therefore, the ancestors wanted the boy’s grave there, near the mentioned objects. The compound head of Akanwari Yeri said that a grave at that location is unusual for such a small boy.

3.2.4 Infants who do not have younger siblings are buried in or near the trash heap (tampoi).

Margaret Arnheim (fn M61a) reports an event related to this in Akanwari Yeri (Gbedema-Gbinaansa): A heavy downpour occurred after using soil from the tampoi as fertiliser for the fields. In the kusung, the collapse of a cavity (a grave?) was heard at the tampoi. The old men could not remember that people had ever been buried there – maybe it was the grave of a horse (with air space). Children are usually buried behind the compound or behind the tampoi.

Adama from Wiaga-Chiok showed me the graves of childless women at their tampoi who had lived elsewhere. Unlike infants, these women’s bodies are buried there at the usual depth (fn 88,180a).

3.2.5 Children with younger siblings are buried along the footpath leading to their mother’s compound. Sebastian Adaanur from Sandema Yongsa (fn 79,26a) reports that a woman’s firstborn child is buried alongside the footpath; later births are buried in the tampoi. Although Akanchainfiik (see below) had several living siblings of the same mother, she was buried at the tampoi, in contrast to Sebastian’s statement.

3.2.6 Children considered kikita – human beings possessed by a malicious spirit (including malicious twins) – are buried far from the compound in the ‘bush’ (sagi). Sometimes, they are even buried in another village and in an ant hill (see also Chapter 3.7. Death and burial of a kikiruk).

3.2.7 After the removal of the foetus, deceased pregnant wives are buried away from the compound (but not in an ant hill), sometimes in a guuk (an abandoned compound).

3.2.8 Burial in old graves, as it happens among, for example, the closely linguistically related Koma, does not exist among the Bulsa.

3.2.9 A discussion in the Bulsa Facebook group Buluk Kaniak dealt with the subjects ‘health’ and ‘treating dead bodies’ (initiated by Augustine Atano, 4 July 2020):

John Akanvariyuei Agandin: …when a corpse is sent to the village in a coffin, they will remove the body and bury it separately and then burn the coffin.

Abakisi Akangagnang Lawrence: …You know our palace is a very old house but keeps expanding, and men, by Buli custom, are buried in the nankpieng. But, because of the longevity of the house and population increases, burying in the nankpieng became extremely difficult. Then, progressive elements within the house, including my late father (may he rest well), advocated for a family cemetery, but there was resistance from conservatives, who saw the serious consequences of such a move. Fortunately, we had a father, our late king [Azantilow], who would give [an] ear to every opinion. To cut matters short, a diviner who okayed the burial in [a] coffin and [the] family cemetery [was brought]. We became [trendsetters] in that regard, and today, almost everyone is buried in coffins and family cemeteries. Other families have since followed suit, and it is catching [on] in Buluk. Also, family members who have died [of] diseases that people are not supposed to touch the body… Such persons are not given the usual cultural treatment like bathing and massaging but are kept in coffins and buried.

The fact that someone has died an evil death (kum-biok) has no major influence on the general location of their grave. However, as already mentioned, women who died of kum-biok are buried at a certain distance from the other women’s graves.

Although tradition determines the local position of a grave, discussions still arise after death as to where a grave should be dug in a specific case. This uncertainty is often even greater regarding the question of which compound a dead person should be buried in. In particular, the burial place of a wife who did not die in her husband’s home is sometimes the cause of significant controversy between residents of her parental home and her husband’s home, both of whom want to carry out the burial as well as the later funerals for the dead.

Similar problems arise when children die during a visit to their mother’s parental home.

In Badomsa, for example, a married man, along with his wife and children, left his parental compound in a dispute and built a new one. Then, after his death, no reconciliation occurred between the old yeri nyono and the widow. Upon her death, relatives from her home village will take her body and bury it at her parental compound. If a child dies while the mother is alive, he would be buried at the new compound (Yaw, fn 08,1).

3.3 The grave diggers and their vayaam medicine

The translations ‘gravedigger’ is not very fitting for the Buli word vayiak (pl. vayaasa) because digging a grave shaft is only one of this ritual expert’s many activities, which also encompass many other ritual matters.

Before starting their work, gravediggers prepare themselves for the dangerous work in their compound (Ansoateng 1994, fn 4b).

3.3.1 The gravedigger Ansoateng

3.3.1.1 Ansoateng’s vocation and activity (fn 88,99ff, 14.11.1988)

Eighteen years ago, many people died in Badomsa, including at Ansoateng’s compound. To the neighbours’ ire, the gravediggers were nearly unable and unwilling to bury all of the dead. Therefore, Ansoateng helped them with the burial process. However, he then became very ill for a long time – he had aching limbs, and his face and body were swollen. His illness arose because he had buried people without vayaam medicine. He had to obtain specific stalks, black herbs, and roots (tinangsa) to make vayaam. For each piece of root, he had to sacrifice a chicken. If, after each sacrifice, the root piece jumped up and landed on a specific place next to the place of sacrifice, it was a sign that the aspirant must become a gravedigger.

Millet porridge was prepared, poured into a hole in the tampoi, and then, using feet to mash and spread it, mixed with sweepings and stones until it had become completely dark. Instead of a stirring stick and a ladle, a human shoulder bone from a grave was used to mix the porridge. The porridge was placed on Ansoateng’s leg, and he ate a bite of it three times, bringing it to his mouth with his left hand. The rest was poured back onto the tampoi, where it suddenly disappeared.

3.3.1.2 Ansoateng’s medicines and activities

Ansoateng’s vayaam-medicine at the tampoi

If someone has died in Wiaga-Badomsa, Ansoateng receives a hint from his vayaam medicine For example, if he has had a very restless night, the following morning, he will go to his vayaam medicine, which he keeps in a clay pot by the rubbish heap (tampoi). When the medicine pot’s lid is slanted, he knows that someone has died. Ansoateng will then refill the pot with water and drink some of the medicine. He also places his hand inside to grasp some medicine and rubs his whole body with it, mainly to protect himself against the dangerous piisim smell of the corpse, which can lead to vomiting and other diseases [endnote 14].

Afterwards, he does not close the pot again. After the burial, he will peer inside it. If the root pieces (tinangsa) lie parallel, he can close the vessel again. If at least one root piece lies across another, there will be another burial soon, and he will leave the pot open.

According to Ansoateng, four types of vayaam medicine exist. All are made from tree roots:

1. Medicine from the roots of the unidentified kpagluk tree, obtained from a crocodile cave by a river. This is the most potent medicine. The gravedigger crawls into the cave and then closes it with thorns to protect himself from the crocodile that might return. Then, he cuts off pieces of the kpagluk root.

2. Medicine from crossing roots of the highly rare and unidentified yik tree.

3. Medicine from the roots of a gaab tree (Diospyros mespiliformis) that never bears fruit.

4. Medicine from the roots of the waaung-duob-pok tree (waaung duob = Prosopis africana?).

Medicine in Ansoateng’s room

Ansoateng keeps these medicines in his pot by the rubbish heap. Children and elderly women – but never childbearing women – can drink the vayaam medicine if they have been attacked by the piisim smell. These drinks are from a ‘white’ medicine that is not kept at the tampoi but in Ansoateng’s room in the compound. Women who must touch the dead can also bathe with a mixture of donkey dung and ngmanyak grass (not identified).

Immediately after death has occurred, the ‘gravediggers’ take over many key ritual acts because, among all those present, they know best what to do in such a situation. Ethnologists who think that the consent of the yeri nyono and the close relatives of the deceased is sufficient to observe and photograph the course of postmortem rites may experience great disappointment when the veto of the first gravedigger blocks their work.

Individual gravediggers have different functions and powers. Some may only dig, while others dig and bury the dead, and others again others may only bury young people (fn 03.32b). For digging a grave and the following activities in a compound, the leadership lies with an older, more experienced vayiak. He is appointed by the elder (kpagi, headman) of the dead person’s lineage, which includes the inhabitants of about 3–4 neighbouring compounds (ko-bisa). However, the official gravedigger is often not directly involved in the physical work. He may be sitting in the kusung with the elders of the compound, making crucial decisions from there and carrying out a few ritual actions on the laid-out corpse. The physically labouring gravediggers also have a leader who carries out other activities aside from the digging work (see below).

Depending on the characteristics and modes of death of the deceased, different vayaam medicines are used:

1) For lepers: without this medicine, burial is not allowed,

2) For a pregnant woman,

3) For a sakpak (a witch or sorcerer),

4) For a sakpak-yiik (the worst kind of sorcerer),

5) For a deceased whose death occurred more than two days ago (i.e. with the onset of decomposition),

6) For the dead still walking around as kokta, coarse red-brown sand is used – the dundum medicine, which is also eaten by others.

My question to Ansoateng on whether he has krupaani (or kurupaani) as a gravedigger was answered with an unequivocal ‘yes’. Without krupaani, he could not do his job; the kurupaarisa are in him. When he sees a sick person, he knows through them whether the person will die (for the definition of krupaani, see also Chapter 3.4.2, endnote 28).

When Ansoateng enters his room with various medicines and sees that part of the pregnant woman’s vayaam has fallen out of the container, he knows that the pregnant woman has died.

Burying babies is more exacting than burying a decomposing person because there must be no mistakes (see also Chapter 3.5.1: Akanchainfiik’s burial). When a child dies as a sakpak, Ansoateng breaks its hands and legs before burial so that it cannot get out of the grave.

He investigates before the burial whether the deceased was a sorcerer or witch by pinching the dead person’s arm. If the dead person pinches back, he is reasonably sure that the deceased will become a ghost (kok), so he tries to find the right medicine. Some gravediggers cut off a dead witch’s hand, ears, nose, or fingernails. If such a dead person bites the leg of a living person, without treatment the person will die after three or four days. The bitten individual seeks out a vayiak, who knocks out a tooth of the dead person in his laying-out room. He puts the tooth in the fire until it turns black. Then, he grinds it, adds some oil to it, and rubs it into the bite wound (on the leg) until it is healed.

He answered my question (again), about the direction in which the dead are buried. The heads of men face south, while their faces are directed east; the heads of women face north, and their faces point towards the west (F.K.: Akanchainfiik was also buried in this position; see Chapter 3.5.1).

If Ansoateng encounters a root while digging a grave, he cuts it on both sides and places it in his pot of vayaam medicine – if he does not do so, someone may die.

Additionally, Ansoateng showed me the dundum medicine (see above), some of which he ate in my presence. Most other medicines must be burnt or charred before one may eat them (fn 88, 100b).

After the interview, Ansoateng showed me two bright crosses (as if drawn with silver bronze) drawn on the window of his room and a round black shard on the wall by the compound entrance, providing another means of protection for the gravedigger.

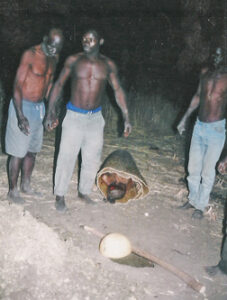

3.3.2 Vayaam rituals at Angaung Yeri, Mutuensa (fn 88,236b)

On 19 March 1989, a leper from Angaung Yeri was buried by the vayaasa from his own and other compounds, including Ansoateng. Each gravedigger’s head was shaved. A medicine was prepared in a bimbili vessel and placed on the tampoi. The vayaam-bogluk was taken from the yeri nyono’s room and placed on the tampoi, where he received the sacrifice of a chicken and a sheep. All the gravediggers and others took a bath unclothed, washing off each body part with the medicine diluted in water.

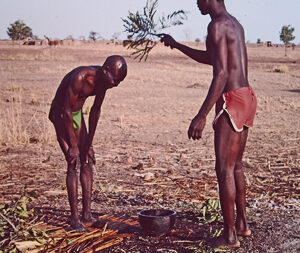

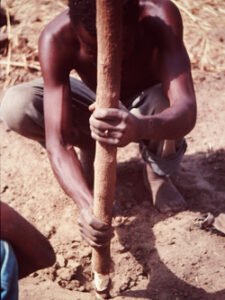

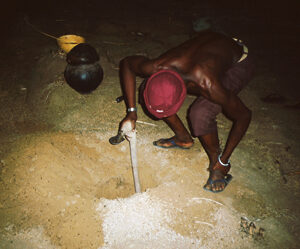

Grave diggers at the trash-heap

On the following day (20 March 1989), I learned more about burial rituals by interviewing people in Angaung Yeri and making observations. In the yeri nyono’s courtyard, the cooked meat of the sheep was distributed to everyone. Some women from their or neighbouring houses went to the tampoi, bared their upper bodies, and washed their heads, arms, and legs. Due to the daylight, they did not fully undress and did not want a photo. A shaven-headed gravedigger demonstrated bathing on the tampoi for me. There were tufts of leaves with which he washed himself off and knocked his body after dipping them into the medicine water. Such a bath also protects against numerous other diseases.

3.3.3 A vayaam ritual in Anduensa Yeri, Wiaga-Chiok

When I had touched Akanchainfiik’s corpse after her death (see below) and touching other dead people was deemed possible for me in the future, I was advised to undergo the vayaam ritual. It would protect me from the harmful effects of smelling a corpse (piisim) and be a preventive measure against ghosts.

Adaapiim, the father of my associate Adama, agreed to perform the vayaam ritual for Danlardy and me at his compound in Wiaga-Chiok.

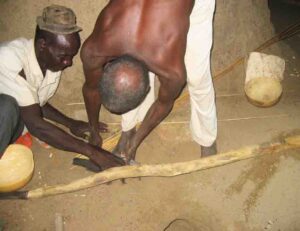

We needed to obtain the following for this ritual: one white chicken (kpiak), one new hoe blade (kui), one jar of shea butter (kpaam), millet flour (zaa), salt (yesa) and one billy goat (bu-duk), whose testicles and penis were needed for the medicine and a medicine bag’s crafting. I was able to buy the goat for 3500 cedis at the compound. The necessary herbal parts (probably roots) would be obtained by people from Adaapiim’s family in the bush [endnote 15].

When we arrived at the compound, some of the collected medicinal species were already in a samoaning clay pot. We were told the names of ten species; three had to remain secret. After adding water, this vessel was placed on fire at 5:30 p.m. Adaapim placed the vayaam-bogluk – a closed calabash with solid, charred medicine – next to the fire. The hoe blade now lay on top of the clay pot and would receive the blood of sacrificial animals. At 6:30 p.m., a brown chicken (provided by the compound) and my white chicken were sacrificed to the two shrines. A problem arose when my white chicken would not flutter upwards after the first cut, indicating that my sacrifice was not accepted. However, after a second cut in the throat, it did flutter up. After speeches (prayers) from the compound head and me, the goat was killed in front of the shrines over a small bimbili bowl that caught the flowing blood. Then, Adaapiim let some drops of blood from the still-bleeding goat drip onto the two shrines; immediately afterwards, the goat was cut into pieces. A young gravedigger took two small pieces of charcoal from the small vayaam-bogluk. With a stone on the hoe blade and a ceramic grating bowl, he separately ground part of them into a black powder and then added salt.

The samoaning vessel on the hearth consisting of three stones

The vayaam-shrine, a calabash with traces of former sacrifices

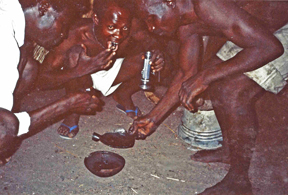

Sacrificing a fowl to the liquid medicine

Charred medicine on the hoe-blade

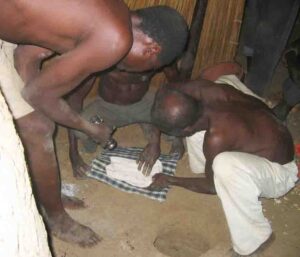

Danlardy and I were then led to our bathing site behind the tampoi, where two unclothed younger gravediggers had just taken their bath. After undressing (I was allowed to keep my pants on) and assuming a squatting position, a gravedigger standing behind us poured alternating streams of steaming hot and cold medicinal water over our heads from a calabash bowl. We had been told that boiling water from the samoaning pot was used for this, but we did not need to fear: If we had not come here with evil intent, we would not suffer any burns. As the hot (boiling?) water was being poured, I ventured a look behind me. Just as the hot water was being poured, another gravedigger was pouring cold water, which mixed with the hot water in the air and on my body.

After this, a man massaged my chest, hit my legs and head with a branch of leaves quite firmly and then, more gently, hit my back.

Danlardy and F. Kröger bathing with medicine-water

Consuming medicine

We were then led back to the hearth with the medicine pot. Meanwhile, the grated and salted charcoal medicine had been mixed with shea butter, and we had to tap our index finger three times (representing the male principle) into two different medicines and eat the medicine. Only adults who have undergone the vayaam bath before may consume this medicine.

At the same time, between the tampoi and kusung, some men had prepared sa-gaang, an unfermented millet porridge. An unclothed man kneaded some millet porridge on the stirring stick and poured liquid shea butter and the black powder over the porridge. After a prayer, the medicine pot on the fire and the vayaam-bogluk received the following offerings from the compound head:

At the same time, between the tampoi and kusung, some men had prepared sa-gaang, an unfermented millet porridge. An unclothed man kneaded some millet porridge on the stirring stick and poured liquid shea butter and the black powder over the porridge. After a prayer, the medicine pot on the fire and the vayaam-bogluk received the following offerings from the compound head:

1. Clear water,

2. Millet porridge from a bowl,

3. Oily millet porridge from the stirring stick,

4. Blood soup (from the killed goat),

5. Two kinds of meat (from the two chickens?),

6. Clear water (medicine water is never sacrificed).

Danlardy and I were each given one leg and wing of a chicken and one foreleg of a goat.

At the eating area near the kusung-dok, we ate some of the millet porridge from the stirring stick. It had taken on a dark colour due to the admixture of the medicine powder. As we ate, several women and Adama’s young son bathed at the bathing place with the vayaam medicine.

Adama’s father, Adaapiim, then called Danlardy and me to the kusung. He handed us a reddish hot medicine from the samoaning. Then, he gave us a piece of the charred medicine to take home and instructed us on its use and effects: We were to grind it into a powder on a hoe blade and mix it with salt and shea butter. It should be kept in the house and only taken before dangerous or nocturnal endeavours; it should never be taken to funerals or visits. We would no longer have to fear ghosts (kokta), but we were forbidden from telling anyone if we had seen a ghost. Finally, the medicine was only for us and must not be eaten by anyone else.

Small pieces of charred vayaam medicine can also be worn on the body in an iron bracelet that has a tubular central part, where an open slit allows the medicine to exert its effect unhindered.

On 2 April 1989, Danlardy and I undertook our second bath in Chiok by having lukewarm medicine water poured over us thrice. We then had to drink the medicine three times again.

On 3 April 1989, I visited Chiok alone in the daytime. There, I was asked to wash myself by pouring the water over my body and drinking the medicine three times.

Two of Danlardy’s stepmothers wished to take this opportunity and underwent the vayaam ritual in Chiok with the same water from the samoaning pot. However, as women, they were required to come four times (representing the female principle). Each of them donated a guinea fowl (kpong) and a chicken (kpiak) as offerings to the two shrines; like us, they bathed by pouring the medicine water over them. They were not fully unclothed but wore traditional leaf clothing. ‘Men’s’ millet porridge (sa-gaang) was prepared as it had been done before, but this time there was a mixture of millet porridge and crushed medicine at the stirring stick that was not offered to the women.

After completing our ritual treatment, Adaapiim made a small bag from the skin of the goat’s testicle. He cleaned it inside using sand and filled it with liquid vayaam medicine, making it a reserve container that, like the small vayaam-bogluk, is kept in the ancestral room (dalong). Adaapiim brings it with him when he must leave the house at night. When I visited the compound on 24 April 1989, the samoaning – the large medicine pot – was still standing at the tampoi.

Upon enquiry, Adama explained that the little vayaam-bogluk could also become a segi (guardian spirit) at a segrika. The children concerned are then called Avayaam, Avayaampok, Avayaamlie, or Atiim (fn 88,252).

3.3.4 Further information on vayaam medicine

Information courtesy of the gravedigger Akperibasi, son of Ayomo Ayuali (fn 88, 188b). His vayaam medicine stands on the tampoi among shrubs. When new roots are boiled for the medicine, many neighbours come and drink from it. The medicine also helps against nausea or the consequences of eating spoiled food. When the gravedigger buries a decayed corpse, he drinks from this medicine and washes his hands and feet with it.

Information from the gravedigger Ayomo Ayuali (20.11.88, fn 88,110a). At the kusung stands Ayomo’s dachoruk (spade), which is used for digging graves as well as postholes. (fn 88, 173b) As gravediggers, Ayomo and his eldest son, Akperibasi, are not allowed to make a dachoruk themselves.

Fowl’s feet outside of Ayomo’s ancestral room

On the outside wall of Ayomo’s kpilima dok hang some chicken feet, which come from a nang fobka ritual (see below) in Sichaasa. It involves an animal’s tail being moved around the death mat three times for a male dead person and four times for a female. Then, a chicken is struck dead on the ground. The chicken was given to Ayomo because he was the leader of the gravediggers. He will use its feet for his vayaam medicine; one day, a billy goat (bu-dok-tiik) and a red chicken (kpa-moaning) will be sacrificed to it on the tampoi. A black hoe blade not yet used for rubbing medicine is added. All those who wish to participate in the ritual have their head’s hair shaved with a loose razor blade. After shaving, water is boiled with medicine (tinang), and all participants have the hot water poured over their shaved heads, armpits, buttocks, and backs of their knees. Then, a chicken foot (see above) will be charred and ground, and oil and glowing charcoal will be added to the mix, producing smoke. All participants will inhale the smoke and hold their elbows, knees and feet over it. They then eat the charred and ground medicine.

If the dead man’s medicine is more potent than his own, Ayomo will die (fn 88,238a).

Information from Adama, Chiok (fn 88,241a): There are two kinds of baths: 1. to allow burying different (e.g. already decomposed) corpses. 2. to prevent encounters with ghosts.

Information from Akanming (fn 88,136a): If an unauthorised person touches the vayaam shrine, he must sacrifice a chicken.

Information from the tiim-nyono of Yisobsa (fn 94,23a): He makes vayaam medicine from the roots of beli-cham and vayaam-tengnang (tinang?) trees by digging up the roots and soaking them in cold water. For example, those who suffer from the effects of piisim and have swollen limbs bathe in this extract. Some roots can also be eaten in their charred state.

3.4 Burial of adults

3.4.1 Death of a married woman (case study from Wiaga-Yisobsa)

Only once was I able to observe and document the entirety of the rites performed for and on a deceased person in all details: In the compound of my assistant, Yaw (Apok Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa, fn 02/3,31a-35b). This was likely because my assistant Yaw was the ‘chief mourner’ (kumu nyono; literally, the ‘owner of the funeral’) on behalf of his father, who lived in southern Ghana, and because Agyenta, the father of my long-time friend Alfred (now the Catholic bishop of the diocese of Bolgatanga/Navrongo), was the leader of the vayaasa.

3.4.1.1 Treatment of the dead woman and rituals before burial

Ama with the death mat

Yaw’s sister, Asiuklie, had died in Sandema Hospital on the night of 3–4 January 2003. Yaw and I had taken her body in the back of a pickup truck to Apok Yeri in Wiaga. If Asiuklie had been buried in Sandema, her death would have been considered a death in a foreign land (sagi; literally ‘bush’), as she had not visited Apok Yeri before returning from southern Ghana. Some soil would have been taken from her grave and buried in a ngarika burial (see below) in Apok Yeri (fn 02/3,35b).

After we arrived in Apok Yeri, they initially wanted to lay the body in the dalong on a cloth, but a man from Apok Yeri was successful in his objection to this, so she was laid on a straw mat (tiak) provided by the Ama of the compound [endnote 16]. When the chosen gravediggers (vayaasa) first entered the room of the dead, they cleared their throats to announce their arrival. They tapped the floor with the flat of their hand four times (thrice for a male dead). Subsequently, they were allowed to touch the corpse.

Laying the dead woman onto the mat

Some older women undressed the dead and put a plain, dark-coloured waist cord on her, into which a leaf apron could also have been hung [endnote 17] if they had not later put a woven strip (garuk-pali) around her hips as a cloth garment. Her old clothes were washed and would later, with other things from her possession, be displayed at the granary (bui) at her funeral celebration. Afterwards, they could be worn by, for example, her younger sister. However, many women are afraid to don the clothes of a dead person.

Next, the women wiped the dead woman’s body with a wet cloth. Shaving Asiuklie’s head hair caused problems in the proceedings, as all those asked to do so refused out of fear. Finally, Yaw – against all traditions – performed this work himself (fn 02/3,33a).

Older women were typically supposed to carry out the massage of the corpse to keep the body supple for burial through a narrow shaft. However, they feared this task, so gravediggers Agyenta and Agbong [endnote 18] carried out this activity (fn 02/3,33a).

3.4.1.2 Suurika (fn 02/3,31b) and other rites

Some other rites had to be performed before the burial. At about 1:40 p.m., Yaw drank a bowl of reddish millet water (zamonta-zom) next to his dead sister; a woman said a few words about it, mentioning that this was a welcome drink for Asiuklie, who had returned from southern Ghana as a ‘stranger’ and had not visited her compound before her death. Yaw drank the millet water in his sister’s place. This ritual is called suurika (here: ‘rinsing the mouth’), tugka (‘receiving [a drink]’) or tutok moangka (‘wetting the throat’).

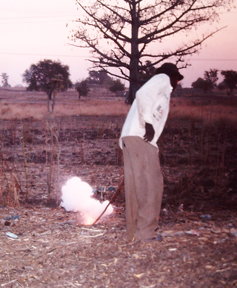

Igniting a firecracker

Before the burial and, the question was asked in the kusung, whether all problems concerning the dead had been solved. Yaw’s mother reported that Yaw had quarrelled with his sister in Sandema. After initial reluctance, Yaw underwent a purification ritual in which he and a compound dweller held a very small, light brown chicken, which was then cut in two in this position (kpiak gebika, fn 02/3,32a+33a; see also Ngarika Burial, Chapter 3.7.2.1, with photo). I was allowed to participate in this ritual. Knowing that photos were probably undesirable, however, I refrained from taking them.

Yaw wanted firecracker shots (dagoong naka) to be fired before the burial, while the oldest neighbour (Asiidem) ruled this out completely, as no shots had been fired at the previous burials of older men. A compromise was found by agreeing to fire two shots: the first for the recently deceased and the second for Asiuklie. Only the names of two deceased men and an elderly woman were mentioned before the first shot was fired, but others were included.

The liik vessel, the calabash bowl and the dachoruk

Immediately before the burial, two women mimed filling a large liik vessel with water at a place between the grave and the compound entrance. Although they made the motion of filling it with a calabash bowl, the bowl was empty. The ‘water’ was meant to quench Asiuklie’s thirst. In other compounds, the vessel may be genuinely filled with water. According to other information from Ansoateng (Badomsa), the water is also used to mix clay mortar for plastering the burial bowl.

The liik vessel with the calabash would remain at the grave until the hanging of the mat (ta-pili yika) – or even for a long time afterwards – and would then be brought to the dalong. According to my informants, water is fetched in this liik for food preparation during the funeral. At the funeral’s end, the woman who organised the widow’s bath receives the vessel as a gift.

3.4.1.3 Announcement of death (kuub darika) and condolence visits

The kuub darika consisted mainly of the notification of Asiidem, the elder (kpagi) of the ko-bisa of Apok Yeri, who lived in a neighbouring house. Asiidem, for his part, notified most of the other relatives.