INTRODUCTION

1. THE COUNTRY

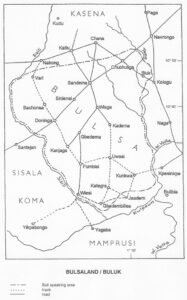

Map of the Bulsa territory (first edition, 1978)

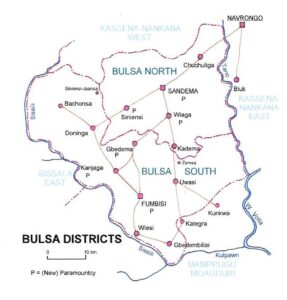

Map of the Bulsa territory (2021)

a) Geographical location and neighbouring ethnic groups

The tribal territory of the Bulsa is located in the far north of Ghana, separated from the northern national border with Burkina Faso (approximately 11°N) only by a strip of land of about 20–25 km wide, which is inhabited by the Kasena, a neighbouring ethnic group. The 1978 map provides information on central places, transport routes, borders, and the Bulsa’s neighbouring tribes. The 2021 map also shows the boundaries of two new districts, Bulsa North and Bulsa South. In the southeast, ethnic and administrative boundaries do not coincide, as the residents of the villages of Kunkwa, Kategra, and Biuk speak Buli, although these villages do not belong to a Bulsa district of the Upper (East) Region.

Visits to Isiasi (Yisesi, in 1984 et al.) and Jaadem (Giadema, 2011) revealed these are Mamprusi villages with either some Bulsa sections or with many residents who can speak Buli. The village of Bulibia is reportedly completely depopulated. Kunkwa and Kategra are Bulsa villages that today would like to return administratively to a Bulsa district. Biuk (south of Navrongo) is an ethnically fairly pure Bulsa village with some Kasena who migrated there later. Villages such as Yikpabongo and Nangrum could be proven to be pure Koma villages, the language of which is closely related to Buli, but whose culture is clearly different from that of the Bulsa (cf. Naden, 1983/84 and 1986; Kröger and Baluri, 2010 and 2020).

b) Climate and the agricultural and ritual annual cycle [endnote 1]

Activities in the annual cyclus

In terms of climate, the Bulsa region belongs to the tropics with an unbifurcated rainy season — the year is divided into two major seasons: the dry season (wenkarik, pl. wenkarisa [endnote 2]) and the rainy season (yue, pl. yua). The shorter rainy season (April to October) is the time for agriculture and when cattle must be herded by shepherd boys to protect the fenceless fields. The hotter dry season (November to March) is the time for festivals, ritual activities, house extensions, building new house foundations, and hunting. However, the farmer, his sons, or his wife sometimes also find time to plant a dry-season garden with artificial irrigation, or the man uses the time for handicrafts such as basket weaving and making stepladders (tiila), while the woman can earn an extra income by making calabashes or pottery or producing shea butter.

Fig.: Kayagsa stick rattle

In the rainy season, ritual life does not come to a complete halt. Often, one can hear the blasts of firecrackers from a funeral celebration or the songs of a wedding crowd returning home. However, many customs, rites, and activities {6} are strictly bound to certain seasons. For example, young girls are only allowed to beat their kayagsa stick rattles (perforated calabash shards strung on a stick) in the period between sowing and the first harvest of early millet, and female excisions take place almost exclusively in the early dry season.

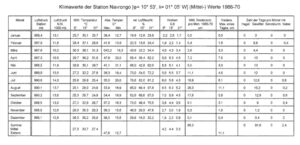

For Europeans, the rainy season would probably be a more pleasant time in terms of climate were it not for the heavy downpours making it challenging to get around via vehicles, because large areas are often under water for some time after the rain showers start. As the climate values in the table (Climate values …) clearly show, March is the hottest month, which is also perceived as very unpleasant by the locals, while the period from August to January is the coolest time, during which many Bulsa complain about the cold nights (cf. Ghana Meteorological Service … 1966–1970).

Climate values of the Navrongo Station – Average values 1966-1970. Translation: (head fields): Air pressure Navrongo, air pressure N.N (sea level). mean temperature, absolute temperature, relative air pressure, clouds, mean precipitation per month, precipitation maximum of a day, number of days per month with hail, sandstorm, fog

c) Soil characteristics and landscape

Geologically, the Bulsa area lies at the edge of the large Paleozoic Volta Basin, whose boundary coincides roughly with that of the Northern Region. In Bulsa country itself, older strata are still present, such as metamorphic lavas of the Upper Birimian in the south (around Kadema), but above all Precambrian granite rocks, which have partly weathered to brown sandy, stony loams or strongly ferruginous lateritic soils and partly come to the surface in boulder fields, block forms, or rock slabs. These give variety to the relief of the land, which is for the most part only weakly moving. Rocky areas cannot really be used in any way by the inhabitants.

The soils are of varying quality for agricultural cultivation, as shown by the soil quality map in the appendix to S.V. Adu’s (1969) work on the soils of the Navrongo-Bawku area. In very simplified terms, the north of the Bulsa area has good to moderately good soil. However, a strip of quite poor soil runs in the middle of the area (around Kanjaga, north of Fumbisi, south of Gbedema, and around Kadema), while the south (north of Wiesi, south of Fumbisi, and south of Uwasi) has the best soils for agriculture {7}, which is also known to most Bulsa.

The land use map in S.V. Adu’s work (Map 4) shows the most extensively used areas of tree savannah are to the northwest and southeast of the Bulsa area, while a wide strip of land from Wiesi to Chana (Kasena) is used more intensively for compound and bush farming.

Savannah landscape near Sandema with grazing cows

In the Bulsa area, the natural landscape is increasingly dwindling due to human interference. In the daily search for firewood and the clearing of timber in the “bush”, young and old trees face the axe. Only fruit trees (e.g., Adansonia digitata, Anona senegalensis, Butyrospermum karii, and Diospyros mespiliformis) are spared more, so that a selection of trees is made here by man, which G. Benneh (1970) already pointed out the Kusase.

However, environmental awareness seems to have become stronger in recent years. In their speeches, Sandemnaab and Paramount Chief Azagsuk Azantilow II (since 2013) often call for moderation in the clearing of bushland, especially shea butter trees, which should not be felled at all as their fruits and their processing into butter could be the basis for a developing industry (see also Chalfin, 2003).

If one finds a small, densely wooded patch of land in the bush or between settlements, one can be almost certain this is a sanctuary (tanggbain), from which no wood may be taken. Thus, it may be asked whether this piece of land became a tanggbain because of its densely forested surface or whether a dense grove developed there because it was considered the seat of a deity.

d) Settlements

Dispersed settlements are the predominant settlement type. Nearly circular compounds, called Sudanic compound houses by K.B. Dickson (1971: 128f.), are surrounded by intensively cultivated fields (e.g., millet, sorghum, groundnut, neri, various types of beans, and rice) and are distributed irregularly over the cultivated land.

The distance between the compounds is usually so great that it is still possible to communicate with the inhabitants of neighbouring compounds by shouting from the flat roofs of round houses. Important messages, orders, prohibitions, and invitations from the chief are often brought by messenger to the house of the sub-chief (kambon-naab, pl. kambon–nalima). From the sub-chief’s house, the message {8} is transmitted to the other houses of the section by means of call connections (wiika, see Aduedem, 2023)

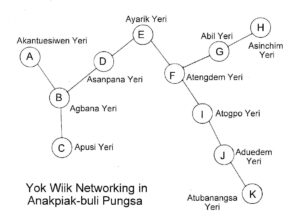

Joseph Aduedem from Sandema-Pungsa has studied the wiik communication system in the neighbourhood of his parental compound (Aduedem, 2023). A message is usually sent in the early evening (yog-wiik, evening message) and often emanates from the village chief (naab-wiik, chief’s message) or one of his sub-chiefs (kambon-nalima), and rarely from the head of a compound (yeri-nyono).

In the case of Aduedem’s neighbourhood, the communication process is as follows:

The network call starts in compound A and ends in compound K

The messages may contain orders or announcements of various kinds. The chief may ask all landlords (yeri-nyam) to come to his palace; all animal owners may be asked to tether their animals; some people or animals may have gone missing; or school will start one day later than previously announced.

Today (2021), the yog-wiik system has been largely replaced by news from Radio Bulsa (Sandema) or calls using smartphone. Almost every family now has at least one smartphone with access to social network, and the “wiika networks” will perhaps be used only for ritual events (e.g., the announcement of a funeral) in the future.

The agricultural fields of a compound do not always extend to those of the neighbouring compound. Strips of grassland and scrub in between are used as pastures for sheep, goats, or cattle.

A small Bulsa compound

The Bulsa compound (yeri, pl. yie) belongs to the type of “Tallensi compound” described by L. Prussin (1969: 59–65) and is very different from the Sisala compounds adjoining them to the west (ibid. 60–80). Most Bulsa compounds have some flat-roofed roundhouses, which are called rooms (Buli: dok, pl. diina) by English-speaking Bulsa [endnote 3]. In some sections (e.g., Sandema-Kalijiisa-Anuryeri), thatched roofs are forbidden altogether, and in the southern Bulsa area, thatched cone roofs outnumber flat roofs by far.

The division of a Bulsa compound into a cattle yard (nangkpieng, pl. nangkpiensa) and a residential part with various stores, chicken coops, and residential buildings was described by R. Schott in 1970 (pp. 14–17) with the Buli names of the various parts of the compound [endnote 4].

The building and social structure of the very large compound Anyenangdu Yeri, as well as changes in its ground plan from 1984 to 1997, have already been described in detail by Kröger (2001: 786–863; Fig. 14.2 to 14.6).

Fig.: Ground plan of the very large Anyenangdu Yeri compound in Wiaga-Badomsa in 1994 (from Kröger 2001: 823).

Near a marketplace, the settlements (e.g., Sandema, Wiaga, and Fumbisi) usually become denser. Gable-roofed houses with rectangular ground plans are more common. Their layout probably dates back to European influence. Not only Bulsa traders and craftsmen live there, but sometimes (e.g., in Sandema) also Nigerians (“Lagosians”), Mossi, and Kantussi. European forms of settlement were still rare in the early 1970s.

The number of modern bungalows has increased considerably since 1974. They are found especially on the exit roads of larger towns (e.g., Sandema, Wiaga, and Fumbisi). While I was aware of only one modern multi-story residential building (in Wiaga) when I started my research (1973), several administrative buildings and schools were later built in all parts of Bulsaland. In Kanjaga, a three-story senior high school building was built in 2017 (cf. Kröger 2017a).

Wiaga is the centre of the Catholic mission (since 1927), with a large round church and several residential and farm buildings, schools, kindergartens, and craft businesses. In 2005, the Catholic Church had two parishes (Wiaga and Fumbisi) and eight outstations. Subsequently, more parishes (e.g., in Sandema) were founded. The Presbyterian mission in Sandema started in 1956–1957. Their church, with some outbuildings, is situated in the eastern part of Sandema.

The profane buildings of solid construction include the resthouses and stations for veterinarians and agricultural experts, the district administration buildings in Sandema, and the schools {9}.

2. THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL STRUCTURE

The Bulsa live in a segmental, patrilineal society with a virilocal marriage order. The system of lineage and lineage segments is highly similar to that described by M. Fortes (1945) for the Tallensi. However, genealogical knowledge seems to be greater among the Bulsa, as almost all living descendants of the ancestor Atuga, who migrated from Mamprusi country in the 18th century (see below), can trace their ancestral lineage back to this man (possibly with the help of a knowledgeable relative). The non-exogamous maximal lineage of Atuga’s descendants breaks down into larger and smaller lineage segments with different functions and meanings. The descendants of Atuga’s four sons live in four central Bulsa locations (tengsa, sing. teng) [endnote 5], which break down further into a total of about 75 clan sections (Buli: diina, sing. dok, English: village, section, or division) that can be localised to specific areas and whose founders, insofar as they are not “foreigners” or “indigenous people”, can be sons, grandchildren, or great-grandchildren of Atuga’s four sons. In my essay “Who was this Atuga?” (Kröger 2013: 69-88), I expressed the assumption that Atuga and his family probably left Nalerigu under the Mamprusi king Na Atabia (1760–1775?) to settle in Bulsaland (ibid., p. 77).

The clan sections, specifically the main lineages of these sections, are often exogamous units (cf. chapter VII,1; {p. 241 f.}). Politically, they (or a group of them) are organised today under a sub-chief (kambon-naab, English: headman or sub-chief), who receives his instructions from one of the 12 Bulsa chiefs [endnote 6].

A clan section usually has lineage segments of different sizes with different functions (Cf. Fortes 1945: 30–38). Rites of passage are primarily a matter for the household community (Buli: yeri or yeni dema) to which people of other (sub-) lineages may also belong. M. Fortes [endnote 7] and J. Goody use the term “domestic family”. Grindal calls them domestic households. This social group (it is not always a lineage segment) will be examined in more detail here, especially since significant differences seem to exist between the Tallensi, LoWiili, and others.

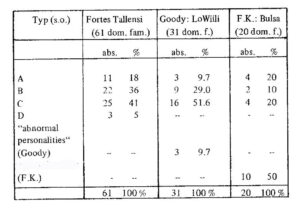

M. Fortes (19673: 64) studied a sample of 61 domestic families among the Tallensi and divided them into the following subgroups {10}:

Type A: Elementary families (man, his wife or wives, his children, and possibly his mother);

Type B: Families whose head is the father of the other male adults;

Type C: Families whose head is the elder brother of one or more of the adult males; and

Type D: Families whose head is the grandfather of the other male adults.

J. Goody (1967:42) applied the same classification scheme to a sample of 31 domestic families in Tʃaa. The result will be compared here with the figures of M. Fortes and with the data from a unit of 20 domestic families in Sandema-Kalijiisa-Yongsa [endnote 8].

{11} Assuming that M. Fortes and J. Goody understand non-classificatory fathers and brothers by fathers, brothers, and so forth in their definition of domestic family types, it can be stated that 50% of Bulsa domestic families cannot be classified in Fortes’ and Goody’s scheme because they have much more complex structures. M. Fortes wrote the following about the Tallensi (19673):

All the men of a joint family [endnote 9] are therefore related to one another through a common father or grandfather or, infrequently, a great-grandfather.

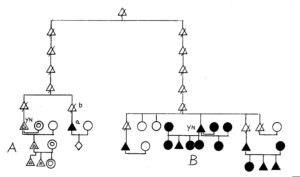

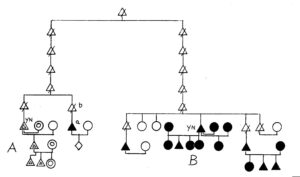

This does not apply to the Bulsa, as indicated above. Some illustrations of genealogical structures for the domestic families listed in the table under “other structures” should show this:

Amoanung Yeri (Kalijiisa-Yongsa) [endnote 10]

(Filled symbols [●]: living members of the domestic family, YN: yeri-nyono, head of the household, head of the family)

Names within the genealogical overview and site plans

(Same numbers as chapter V, 3d {p.184}

7. Amoebina;

8. Ajiak;

9. Asiadi;

10. Anyaribe;

11. Ayomo;

12. Amoanung (builder of the Amaonung Yeri compound);

13. Ateng;

14. Akajoluk;

15. Akonlie;

16. Awarikaro;

17. Akamaboro;

18. Awaabil;

19. ?

20. Anyalape;

21. Achimalie;

22. Angang;

23. Asinieng;

24. Abalansa;

25. Afankunlie;

26. Adocta;

27. Azonglie;

28. Apatanyin;

29. Abamagsimi;

30. Abenab;

31. Asagi;

32. Abankunlie;

33. Akankpewen;

34. Apogma;

35. Afenab;

36. (from Siniensi);

37. Asiensalie;

38. Kofi;

39. Afua;

40. Talata;

41. Child still without name;

42. Baba;

43. Comfort;

44. Alice;

45. Timothy;

46. Mary;

47. Azangbiok,

48. Awatie;

49. Martin Assibi;

50. Kwabena;

51. Angawomi;

52. Assibilie;

53. Kwabena;

54. Lariba;

55. Aguare;

56. Talata;

57. Achipagrik;

58. Aghana;

59. Anamoanung (Anamuning);

60. Akuruma;

61.?;

62.?; and

63. Adocta (in Siniensi).

{12} As the example shows, the common ancestor of the older male adults of the house lived four generations ago. An even more complex picture emerges with the household communities of Anagba Yeri (A; symbols outlined) and Agbedem Yeri (B; symbols filled in).

Person a lives in the residential community of B, although he has much closer kinship relations to the A family. The yeri-nyono (compound head) of B would have to call a his “father” (ko), since a belongs to an older generation. However, a can never become yeri-nyono in B, but only in A; a sacrifices to his father b in the house of the B family, among whose ancestral shrines (wen-bogluta, sing. wen-bogluk) the wen-bogluk of b is also located.

Outside the Yongsa study unit chosen here, even more complex house communities could be recorded genealogically. In some cases, the householders are said no longer to know how they are related to some groups in the same compound. Sometimes they may be descendants of strangers or slaves who were absorbed into the household community. Although these groups have also acquired a great deal of economic independence over time (they are usually allowed to own their own cattle), the head of the compound (yeri-nyono) is nevertheless solely responsible for the well-being of the house in terms of rituals. As the following description of the Bulsa rites of passage shows, he often plays a greater role in these rites than, for example, the father (genitor) of the person who is subject to the rites {13}.

The political structure in Bulsaland has changed considerably since 1974. At the time of my first research stay (1973–1974) it consisted of one district with Sandema as administrative capital and 12 chiefdoms under the Paramount Chief Azantilow (simultaneously the chief of Sandema). The area was divided into two districts on 29 June, 2012: the Bulsa North District, with Sandema as capital, and the Bulsa South District, with Fumbisi as capital (see map 2021 above). The position of the paramount chief was not affected by this until 2018, when several additional “paramountcies” were created: Fumbisi, Kanjaga, Wiaga, Siniensi, and Gbedema (cf. Kröger…).

3. ETHNOGRAPHIC LITERATURE

a) Bulsa

Ethnographic remarks about the Bulsa are found sporadically in older works based on field research which comprises a much larger study unit [endnote 11]. Therefore, the yield is also very small when modern ethnologists examine these works for depictions of rites of passage.

Binger (1892: 36) made a brief remark about the Bulsa tribal marks as early as 1892, as will be discussed later.

In a chapter on the Boura – who, according to R. Schott (1977: 87) and K. Dittmer (1961: 1), can be equated with the Bulsa – L. Tauxier (1912: 275–294) provides some information on the social conditions and the religion of the “Boura”, but his description leans heavily on his preceding description of the Nankana. He claims that the institution of the bride price exists among the “Boura”, while A.W. Cardinall (1920: 76) stated some years later that the Kasena and Bulsa are unfamiliar with the bride price. Cardinall’s statement agrees with my own observations, if one does not want to call small gifts to the bride’s parents a bride price. However, Tauxier does not consider these gifts, as he gives concrete information about the bride price, to which the gifts to the parents must be added (p. 281f.):

Chez les Bouras la dot est de 10.000 cauris payés au moment du mariage, plus une prime à la famille, au fur et à mesure des enfants que celle ci vous donne. Ainsi pour un premier enfant on donne deux bœufs, pour un second on ajoute un bœuf, pour un troisieme on ajoute encore un bœuf, mais on ne va jamais {14} au delà de quatre bœufs – C’est le maximum. Du moins est-ce ainsi que cela se pratique à Sinésé. A Bationsé , la dot est fixe et non variable: on donne 10.000 cauris et deux vaches [endnote 12].

Translation:

Among the Bouras, the dowry is 10,000 cauris paid at the time of marriage, plus a bonus to the family, according to the number of children the family gives you. Thus, for a first child, two oxen are given, for a second, an ox is added, for a third, an ox is added, but never {14} more than four oxen – that’s the maximum. At least this is how it is done in Sinésé. In Bationsé, the dowry is fixed, not variable: 10,000 cauris and two cows are given [endnote 12].

In the case of divorce, according to Tauxier (p. 284), the bride price [endnote 13] is never reclaimed, even if the wife has not borne her husband any children. The following justification is given (p. 285):

Du reste, les maris ne se risquent pas à la réclamer, car, s’ils le faisaient, me dit un de mes interlocuteurs, ils ne pourraient jamais trouver dans le village une autre femme.

Translation:

Besides, the husbands do not risk asking for it, because if they did, one of my informnts told me, they would never be able to find another wife in the village.

The reasoning does not seem to be entirely valid, especially if by village one understands a clan section (Bulsa; English: village), for which a husband would not forego the possibility of marriage into a single one of over a hundred Bulsa sections if he received a handsome bride price in return. However, a similar explanation to the above was given to me by some young Bulsa regarding the courtship situation. They said it was often more advantageous not to ask for small gifts (e.g., coins, salt, or kola nuts) back after an unsuccessful courtship, otherwise it would be difficult to marry another girl from that section.

Other statements by Tauxier that would be relevant to the topic of this work, such as the “household of three” or the attitude of the “Boura” to adultery and premarital sexual intercourse, will not be discussed here, as Tauxier refers to the town of Savélou, which probably does not belong to the Bulsa region. However, according to R. Schott (1970: 88), it is possibly identical to the Dagomba town of Savelugu.

The first edition of R.S. Rattray’s two-volume The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland was published in 1932, and the author deals with the history and tribal and clan organisation of the Bulsa over just more than five pages (pp. 398–403). On p. 400, he also includes some remarks about and a drawing of the Bulsa tribal marks. Unfortunately, he probably made the mistake of considering the smaller scars given to a child after previous miscarriages (cf. chapter IV, 5 {p. 128ff.} of the present work) {15} as part of these tribal marks. Especially in Kanjaga, the hometown of his informants, the small biakasung (miscarriage) scars and tribal scars are cut in an intersecting manner, as shown in his sketch. However, the author had already found that the long cuts also occur without the smaller cross-cuts, and vice versa. Rattray finds it doubtful that these scars should have the function of tribal identification. I do not know whether he was aware of C.H. Armitage’s 1924 work on The Tribal Markings and Marks of Adornment of the Natives of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast (1924), in which the author provides some information on Bulsa scars after miscarriages.

On p. 403 of his work, Rattray mentions female excision, which he calls incision, and the now almost extinct filing of the incisors, which according to my research was common in earlier times, especially in Kanjaga. In the final sentence (p. 430), Rattray states the following about the Bulsa:

Their other customs, like themselves, appear to be a mixture of Nankanse and Kasena-Isala practices. The former have been fully dealt with elsewhere and I will leave an investigation of the latter until I come to examine these rites in their purer state practised by these Kasen- or Isal-speaking tribes themselves.

In my opinion, even today it cannot be said with certainty which ethnic group in Northern Ghana transmitted rites and customs to other ethnic groups or which appearance is to be regarded as “pure” or as a “mixture”. As long as the cultural-historical influence of the Nankanse and Kasena-Isala on the Bulsa is not proven, it could be just as conceivable that the Bulsa influenced their neighbouring tribes, or, as seems more likely to me, that all the mentioned ethnic groups developed culturally and ritually from a common foundation {16}.

Rattray’s work was followed by decades in which nothing substantial about the Bulsa appeared, so that in 1959, K. Dittmer (p. 110f.) placed the Bulsa on a list of tribes that had been insufficiently researched.

In 1970, the first work dealing exclusively with the Bulsa appeared: R. Schott’s Aus Leben und Dichtung eines westafrikanischen Bauernvolkes, and in the subsequent years, he published further essays and books on the Bulsa, as did his students (see bibliography). For my present work, R. Schott’s 1970 book was of great importance. Though it contains little material on rites of passage, chapters III (Teng: The Earth in the Life of the Bulsa) and IV (Wen: Heaven and Ancestors in the Life of the Bulsa) in particular provide a good introduction to their religious life. However, even more important for the preparation and execution of my work, was that R. Schott kindly made his unpublished field research material from the years 1966–1967 and 1974–1975 available to me, as far as it was relevant for my work, and I could evaluate it together with my own field notes.

After 1974, the situation with regard to primary literature on the Bulsa changed fundamentally. Mainly members of the Institute of Ethnology at the University of Münster (B. Meier, D. Blank, U. Blank, S. Dinslage, and myself) together published about 170 papers and some books on the Bulsa in the period up to 2021.

While R. Schott devoted himself to narrative research, traditional religion, legal ethnology, and many other topics, D. Blank (1981) investigated the traditional forms of Bulsa organisation. B. Meier wrote her doctoral thesis on the doglientiri relationship and subsequently published further papers on this topic. Later, she devoted special attention to migration research. U. Blank wrote her master’s and doctoral thesis on ethno-musicological topics. I published books and essays on the following topics: religious ethnology, history, material culture, and African linguistics (the first Buli-English Dictionary was published in 1992).

As a researcher at the African Studies Centre (Leiden), P. Konings wrote several articles on economic subjects (e.g., rice-farming; 1984).

Several linguists from different countries have dealt extensively with the Buli language. British linguists (e.g., I. Gray, C. Gray, T. Poulter, R. Schaefer and N. Schaefer, and P. Dancy) made the results of their research on the Buli language available to the Ghana Institute of Linguistics, Literacy and Bible Translation (GILLBT). It should also be mentioned that through the numerous, mostly anonymous, publications by GILLBT, a rich corpus of writings in the Buli language emerged, covering not only Bible translations but also topics from almost all fields of life (see Buluk 2, 2001: 34).

Numerous linguistic publications were also produced by A. Schwarz (Berlin) and G. Akanlig-pare (Legon).

In recent times, the number of Bulsa studying their own culture has increased. Often, but not always, their writings are unpublished examination papers (e.g., those by J. Agalic, R. Apentiik, F.A. Azognab, St. Azundem, J. Aduedem, and J.A. Agandin). Excerpts from their papers have been published in the Buluk Journal (see bibliography).

b) Neighbouring ethnic groups

In interviews with Bulsa about the rites of neighbouring ethnic groups, the informant often states that, apart from smaller differences, “they” do everything similarly. This is not surprising, since all neighbouring tribes, together with many others, were assigned to a common cultural area in the past, which is generally known as the Volta Cultural Circle. A critical comparison of all Bulsa rites with those of neighbouring tribes, as far as these are known from the literature, would go beyond the scope of this work. Here, reference should be made to some important accounts of ethnic groups in northern Ghana [endnote 14]. Again, there is no way to omit the works of Tauxier (1912 and 1924), Cardinall (1920 and 1931), and Rattray (1969). The latter, for example, discusses the most important rites of passage among the Nankanse (vol. 1, pp. 130 – 214) in detail, but {17} these rites and other cultural elements are said to be paradigmatic for the other tribes of the Ashanti hinterland. Therefore, Rattray regards the Ashanti hinterland, to a great extent, as a somewhat homogenous cultural unit.

Among the ethnographies on ethnic groups in northern Ghana, the publications by M. Fortes on the Tallensi stand out, especially the two main works, The Dynamics of Clanship among the Tallensi (1945) and The Web of Kinship among the Tallensi (1949). Since Fortes deals mainly with relationships between different lineage segments, as well as between exogamous clans, it is not surprising that rites of passage such as permitted and prohibited marriages, courtship, divorce, and remarriage occupy a great deal of space, along with topics such as the theory of conception, pregnancy, birth, facial scars and excision.

Regarding the personal yin (Buli: wen), Fortes (1967: 227ff.) reports that it exerts a fateful influence on Tallensi lives. Generational conflicts can be explained by the antagonism between the yin of father and son. While these statements also apply to the Bulsa concept of wen, Fortes notes that for the Tallensi, the yin can determine human fate even before birth (cf. Zwernemann 1960: 187–196) and that certain ancestors can reveal themselves to a young man as his yin after a misfortune or illness. Then, the young man builds a shrine for the ancestors in question, to whom he will subsequently offer sacrifices. No such connection between ancestors and the personal wen exists among the Bulsa. The creation of ancestral shrines among the Bulsa is just a reshaping and enlarging of their personal wen shrines that the ancestors had acquired in their lifetime.

Regarding ethnic groups in the northwest of present-day Ghana, some relevant works by J. Goody appeared in 1956 and 1962. They will be discussed in more detail elsewhere in this work [endnote 15].

K. Dittmer’s remarks in his monograph Die sakralen Häuptlinge der Gurunsi im Obervolta-Gebiet (Westafrika; 1961) on the kwara of the Kasena and Nuna (p. 139) are of particular interest in this context: {18}

… ein kwara ist ein Fetisch, der seinen Besitzer zu einem bestimmten Amt bzw. Beruf befähigt und seiner Tätigkeit Erfolg und Schutz gewährt.

Translation (F.K.): A kwara is a fetish that enables its owner to hold a certain office or profession and grants success and protection to his activity.

Besides the house kwara and farm-kwara, almost every house has children’s kwara, about whose construction Dittmer remarks (p.138):

Am dritten bzw. vierten Tag nach der Geburt eines Knaben oder Mädchens erhält das Kind vom pater familias seinen Namen und wird mit einem Huhnopfer dem Schutz des Hauskwaras anempfohlen. Zugleich wird eine etwa faustgroße Kugel aus heiliger Erde vom Erdaltar, mit Mehl von kleinkörniger Hirse gemischt und geformt, das ist das Kinder-kwara. Es wird mit Hirsewasser, einem Huhn und einem größeren Tier – etwa einem Schaf – beopfert und erst neben das Neugeborene gelegt.

Translation (F.K.): On the third or fourth day after the birth of a boy or girl, the child receives a name from the pater familias and is recommended to the protection of the house kwara by sacrificing a chicken. At the same time, a ball about the size of a fist is formed from sacred earth from the earth altar, mixed with flour of small-grained millet; this is the child’s kwara. It is offered with millet water, a chicken and a larger animal – such as a sheep – and first placed next to the newborn.

A similar rite, associated with the earth-cult and simultaneously reminiscent in some respects of the wen-piirika (chapter V, 2 {p. 146 ff.}) does not exist among the Bulsa.

The Isala (Sisala) of northern Ghana had long been one of the less researched tribes (Cf. Dittmer 1959), but several monographs have appeared in recent years. In E.L. Mendonsa’s first publication (n.d., before 1973), he summarised and analysed the existing material on the Isala (e.g., by Tauxier, Rattray, Cardinall, and Zwernemann). In 1982, he analysed the activities and social significance of Sisala diviners. B. Grindal’s work (1972) is based on the author’s field research on education and transition among the Sisala. Grindal’s study includes descriptions of some rites of passage. Apart from some similarities with Bulsa practices (e.g., keeping the pregnancy secret until water is poured), the Sisala rites contain a number of individual elements that are unknown among the Bulsa (e.g., a wrestling match between one boy from the husband’s house and one from the wife’s house after a pregnancy has been announced).

In 1974, C. Oppong published a monograph on the Dagomba, Growing up in Dagbon (1974). Her account of transitional stages in the life of Dagomba children and the associated rites (pp. 33–37) shows strong similarities with {19} the rites and views of the Bulsa, for example in the theory of procreation (the physical descent of the child only from the father), keeping a woman’s pregnancy secret until it is announced by her husband’s sister (but without pouring water), and the provisional naming of a newborn child (Saando or Saanpaga = stranger; Buli: Asampan or Ajampan; cf. Buli nichano = stranger). Major deviations in the Dagomba rites from those of neighbouring tribes can sometimes be explained by Islamic influence, for example the Islamic naming with circumcision of the male child, which sometimes takes place after a traditional naming ritual (Oppong, p. 36). In this case, a diviner can identify the ancestor who was reborn in the child and to whom the child has a particularly close relationship throughout its life (cf. chapter IIIA,3,d; {p. 79ff.}).

Several publications with more comprehensive questions appeared on the Kusase (Kusasi) in the extreme north-east of Ghana [endnote 16]. In 1967, E. Haaf published a monograph, which describes itself as a medical-ethnological study but also deals very precisely with the rites and religious ideas of the Kusase. In the following points, many religious ideas, practices, and rites among the Kusase correspond to those of the Bulsa:

1. A pregnant woman must not eat honey.

2. Birth is made more difficult by anaesthetics.

3. Difficult births or miscarriages are often attributed to moral faults on the part of the woman giving birth.

4. The afterbirth is buried between two broken pots near the compound.

5. The male (female) child is taken out of the house (Buli: dok) after three (four) days.

6. In case of earlier miscarriages, mutilations are performed on the child {20}.

7. Infants can be reborn.

8. A metal moon is hung around children born on a new moon.

9. Ancestors become guardian spirits of the children when names are given.

10. The main criteria by which names are given and the type of names are similar for both ethnic groups.

11. Weekday names are often chosen for girls.

12. A child born after several miscarriages is given the name “slave”, and “slave scars” are cut to deceive the evil spirits.

13. Excision (clitoridectomy; the Kusase also remove the labia minora) is performed on girls (usually at a pubertal or prepubertal age).

14 The traditional circumcision of boys does not exist.

15. Both ethnic groups are familiar with initiation ceremonies for young people.

16. Two types of wedding customs are mentioned: kidnapping of the girl and arrangements with the parents (the Bulsa regard the latter as a custom from bygone times).

Only a few deviations in the rites of the two ethnic groups can be identified. However, it notot be definitively assumed that a rite does not exist among the Kusase if it is not mentioned in Haaf’s medical-ethnological study. These deviations include the following:

1. Haaf does not mention a “proclamation of pregnancy” with water being poured.

2. After birth, the Kusase apparently do not “blow ashes” [pobsi], but ashes are thrown into a stream together with the umbilical cord.

3. After a miscarriage, a stranger can become a kind of “godparent” to a child. The child is named after the tribe of this stranger.

4. The Kusase pay a real bride price (e.g., four cows and other payments).

5. After adultery, the guilty couple does not beat each other with a chicken, as is the custom among the Bulsa, but only kill a chicken to reconcile the earth {21}.

The greatest difference appear to be in the understanding of the terms wen (Kusal: win; Haaf, p. 23: … “a second, immortal, predominantly spiritual existence”) and chiik (Kusal: siik, Haaf, p. 29:.. “a vital principle closely connected with the fate of the body”). According to the Kusase conception, the win descends from heaven even before birth, having been allowed by God (widnam) to choose its own destiny in life [endnote 17]. It is then absorbed by a man (e.g., by drinking water) and is passed on by him to the woman during intercourse and by her to the child. Only at a “marriageable age” (p. 24) does a young man erect a bagr (“altar”; Buli bogluk) for his win by fetching some earth in a horn from the place where the win descended from heaven. The horn is placed on the mud altar. Haaf does not mention a wen stone (Buli: tintankori, pl. tintankoa) in this context {22}.

To discuss all post-1978-publications on ethnic groups in northern Ghana would go beyond the scope of this work. I would only like to mention the works of a few authors here. In addition to those mentioned above, their work has been very useful to me, although most of them are less concerned with rites of passage. These authors include S. Dinslage (1981; excisions), S. Drucker-Brown (1999 et. al.; Mamprusi), E. Mendonsa (1975, 1982, and 2001; Sisala), and V. Riehl (1993; Tallensi).

4. DISCUSSION OF THE TOPIC

The term “rites of passage” (rites de passage; rites of transition; rites of a life crisis) is used quite frequently in ethnographic literature, but often with different meanings.

When Goldammer’s Dictionary of Religions (1962) refers to rites de passage (in a narrower sense) as purification rites, this interpretation probably does not correspond to common usage. In a broader sense, rites de passage are (according to the dictionary’s definition) “rites of passage such as youth consecrations and initiation rites or other consecrations of decisive stages of life (marriage)”. In my opinion, the term “consecration” describes the rites associated with individual life stages only inaccurately, and one would have expected the definition to include at least birth and funeral rites as further examples of rites of passage.

Most authors seem to agree that the rites accompanying the ascent to another position at crucial life stages can be described as rites of passage. However, opinions differ on which rites exactly belong in this category. For example, P. Sarpong (1974: 71) argues as follows:

All over Africa, and, in fact, all over the world, significant rituals and ceremonies are, with varying degrees of intensity and seriousness, performed at the three major turning points of a man’s life. In the so-called primitive societies, these rites are collectively termed rites de passage (rites of passage from one stage to another).

The crucial turning points are generally held to be:

(1) the time a person enters the world through birth;

(2) when he comes of age, and enters the world of adults; and

(3) when, through death, he departs from this world and enters the world of his forebears.

{23} In other accounts, such as that of E. Dammann (1974: 71), rites of passage are often understood as the rites of the transitional stages of birth, initiation, and death, while Rattray (1969; 288) mentions birth, puberty, marriage, and funeral customs as rites of passage. G. Parrinder (1969: 79) names the following rites of passage: “… birth, adolescence, marriage, and death, and for some people ordination as well …” Even this definition of the term “rites of passage” seems to be somewhat too narrow for my treatment of this topic, especially since A. van Gennep (1909), who coined the term, saw it in a broader framework. He includes all rites accompanying crises in human life and includes the three phases of separation (separation), transition (marge), and reintegration (agrégation). As typical situations that can be accompanied by rites of passage, van Gennep names the following examples: birth, adoption, initiation, transition to another age group, betrothal, marriage, pregnancy, and burial, although he also emphasises that not all rites related to birth, initiation, marriage, and so on are only rites of passage (ibid., p. 15):

Aussi les cérémonies du marriage comportent-elles des rites de fécondation; celles de la naissance, des rites de protection et de prédiction; celles des funérailles, des rites de défense; celles de l’initiation, des rites de propitiation; celles de l’ordination, des rites d’appropriation par la divinité, etc.

Translation:

The ceremonies of marriage therefore include fertilisation rites; those of birth, protection and prediction rites; those of funerals, defence rites; those of initiation, propitiation rites; those of ordination, rites of appropriation by the divinity, and so on.

Additionally, rites of the threshold, welcoming rites, and rites at a river crossing or at house foundations can also be considered rites of passage (ibid., pp. 26–30). The Bulsa are also familiar with rites of the threshold. The ritual of reintegration of a wife who left her husband a long time ago and before returning, and the kabong-fobka ritual after adultery, take place in front of the compound entrance (see chapter IV).

The obligatory, extended, and often highly specific greeting of a guest in front of the compound cannot be regarded as a mere formula of politeness, and the rites at the founding of a new compound are in some respects very similar to the rites as they are performed at birth and circumcision (cf. conclusion 3; {p. 326f.}). From this point of view, one must agree with A. van Gennep {24}.

I have adhered neither to van Gennep’s narrower (p. 22 f.) nor broader definition of the term “rites of passage” as a guideline for the selection of rites to be described here. This was not done to contrast another definition of rites of passage with those mentioned. Other reasons were decisive.

The starting point for the work was not a definition of terms, but a young person who grows up in the community of their tribal brothers and sisters, who experiences the traditional rites of the tribe in certain stages or life-crises and has to come to terms with them. For these reasons, it was also considered appropriate frequently to quote young Bulsa with modern attitudes mentioning those attitudes.

For several reasons, the idea of death and funeral rites were not described in the first edition {25}. The Bulsa commemorations of the dead, which last several days, are of such complexity that describing them would be beyond the scope of a PhD dissertation (the first edition), especially if ideas of the afterlife, mourning customs, inheritances, and so on are taken into account, as J. Goody did in his 452-page monograph on the burial customs of the LoDagaa (1962).

Moreover, rites of passage associated only with certain occupations, such as those performed when a diviner (baano), a medicine man (tiim-nyono), a specialist in fairy births (kikiruk paro) or in twin births (yibsa tebro) is inducted into office, were not considered here.

However, acts have been described that are clearly associated with the transition of a person into another social position, but do not (or no longer) show a clear religious connection, as the use of the word “rite” actually indicates. Among the Bulsa, these include some wedding customs and the scarifications I have described in a separate chapter. For young people in the traditionally minded Bulsa society, cutting the tribal mark is also an important step towards becoming a fully accepted adult, because only with tribal characteristics and after this first test of courage are they regarded by many tribesmen as a true Bulo.

G. Parrinder [1969: 81) also sees this problem but considers actions that have lost their religious component as rites of passage, saying, “Although marriage is a rite of passage, going from one state to another, its religious side is not distinctive…”.

However, one should bear in mind that the Bulsa do not distinguish clearly between religious and profane acts [endnote 18]. This is particularly evident in the social and medical areas. Whenever a change in the composition of the household takes place (e.g., through long visits by strangers, journeys, inhabitants moving out, or planned marriages), the ancestors must be informed and sacrifices may be made to an effective medicine (tiim) or to ancestors {26}.

When I wrote this dissertation on rites of passage after 1974, I was not yet familiar with the highly significant works of Victor Turner (1967 and 2005). This British ethnologist conducted field research among the Ndembu in Zambia and also included other ethnic groups and societies in industrialised nations in his considerations.

In his extended research on rites of passage, his main interest lay in the second phase, called rites de marge by van Gennep (also translated as “threshold” or “transition phase”), to which Turner refers as the “liminal phase”. He identified elements of this phase in religious and secular communities in other traditional ethnic groups or industrial nations (e.g, in matrilateral groups in patrilineal systems, in monastic orders, and among hippies). For such communities, to which he assigned certain characteristics of the liminal phase, he uses the term communitas, a community existing in contrast to the social structure of the established society. Typical characteristics of the members of a communitas (2005: 123) include:

– Filling gaps within a social structure;

– Staying at the borders of the established society; and

– Occupying the “lowest rungs” in a society.

“Communitas has an existential quality; it concerns the whole person … Structure, on the other hand, has a cognitive quality; it is … a system of classification, a model of thought and order by means of which one can … regulate public life …” (p. 124).

An attempt to apply the communitas concept to the Bulsa’s rites of passage involves some difficulties. The Bulsa do not have any formal initiation rites involving seclusion of the neophytes. In the excision of girls, the girls to be excised do not form a community. They travel from different villages to the circumcision site and become acquainted for only a few hours. The circumcised girls in a compound – today, there are rarely more than two or three – live, as I was able to observe in a single case, in the quarters of the compound head’s first wife (Ama) until their wounds have healed. Here too, however, no community in the sense of a communitas develops, as these girls constantly visit their own family (within the same compound) and sometimes even perform routine domestic chores.

At funeral celebrations, the deceased’s group of close female relatives is given a special status, marked by red body paint and the wearing of red caps. Only the widows (who are not painted) are temporarily secluded in the funeral compound. The other close relatives participate in the social aspect of the funeral. Therefore, the characteristics of a communitas do not apply to them either.

Van Gennep considers ordination as a rite of passage. Among the Bulsa, elements of rites of passage also appear in the ordination of a chief (e.g., his seclusion in a dark room may be called a phase of separation) and in the initiation rites of a gravedigger (vayiak), who is, according to some information, enclosed in a grave with a dead person.

More pronouncedly, the investiture (jadok-gobika) of a Bulsa diviner (baano) exhibits elements of rites of passage, as I was able to observe at a jadok-gobika in Wiaga-Goldem on 1 and 2 May and 13 May, 1989. Although the neophyte was mostly in the courtyard of Asinyang Yeri during the event and later also in front of it, he was largely isolated from the householders and the officiants coming from outside. The latter greeted all the important household members but not the neophyte. After taking a strong medicine, the neophyte lay unconscious in a dark room (dok) without any contact with the others. His reintegration into his social environment, and especially into his new status as a diviner among the other diviners, took place after the completion of the rites in the second phase on the morning of 13 May in front of the compound, when the five diviners from Badomsa played the roles of his clients while explaining the technique of divination to him.

In my estimation, elements of communitas as defined by Turner also appeared in the diviner’s installation ceremony. While diviners usually perform their divination only with their client, at the jadok-gobika all the diviners from the officiant’s section (Akanming from Badomsa) acted as a closed group. In the case I observed, they performed most of the rituals in the Goldem compound. They produced the neophyte’s divination tools and taught him their use. The highlight in the demonstration of their togetherness was probably their dance with the musical accompaniment of their rattles (which they otherwise never use as musical instruments) at the exact moment when the neophyte inhaled his narcotic medicine.

After the jadok-gobika, as far as I know, no further co-operation takes place between all the diviners in a section.

Moreover, I believe that for a certain group of young people among the Bulsa, the designation communitas may indeed be justified. These are the groups of young herders who drive their fathers’ cattle into the bush during the rainy season to protect the crops from grazing cattle (see Aduedem 2020 and Kröger 1987). As a group, they have several characteristics of a communitas:

1. They no longer belong to an age group integrated into the traditional social structure. They are regarded neither as small children, who are still highly protected by their parents, nor as adult men, who earn their family’s living by farming. The shepherd boys, aged around 9–14, are in a transitional phase, the beginning and end of which is not marked by traditional rites.

Wrestling match between shepherd boys

2. The principle of equality between all members is realised to the extent that differences in age, sex, the father’s status (e.g., as chief or elder of a large lineage segment), school education, or knowledge of modern society no longer have any meaning in the pastoral group [endnote 19]. Its structuring is performed through a method without an equal in the social structure of the lineage, namely wrestling matches. Through these matches, a continuous hierarchy is established for which the outdated term “pecking order” would perhaps be appropriate. Each individual has command and punitive power over those below him in the “order” and can, therefore, impose arbitrary, cruel, and degrading punishments, such as drinking urine. However, he must absolutely obey the members above him. Here, a certain similarity can be observed to the neophytes of an initiation group, who are bound to strict obedience to the superior and often have to suffer painful procedures.

3. In their lifestyle, the pastoralist group largely resorts to low forms of economy, such as gathering fruits and hunting small animals (rats, snakes, or hares) with sticks or clubs. Their clothing also corresponds to this lifestyle. They are either completely naked or dressed only in torn pants or shorts. These activities, as well as their equipment and clothing, show they are on the “lowest rung” of the existing society (cf. Turner, 2005: 123).

The peculiarities and weaknesses of the pastoral group are also acknowledged by J. Aduedem, a Catholic seminarian who described his six years of pastoralism (2020: 53), and interpreted them as a kind of endurance test:

… the hardships one went through: the wrestling, the exposure to rains and thunderstorms, the caning by farmers, the piercing of thorns because of the bare footing, the walking in the thick forest alone in search of a lost cow … were preparatory grounds for the shepherds in order to be able to withstand the challenges of adulthood.

4. In their view of life and morals, the shepherds deviate greatly from the ideas of structured society. In addition to the harsh, often arbitrary punishments mentioned above (sometimes harsher than a father’s chastisement), a certain justification exists for theft from farmers’ fields, which they were supposed to protect from grazing cattle. J. Aduedem must intuitively have recognised the existence of a double standard of morality when writing the following (2020: 49):

Again, this presentation should be read in the context of the Builsa worldview of shepherding so that, while some activities of cowboys might be read in the light of today as vices/bad behaviour, [but] they are courageous acts …

Despite the close resemblance of the Bulsa pastoral group to the communitas described by Turner, some important differences can be identified. The pastoral group reconstitutes itself at the beginning of each rainy season, with some new participants and a structure determined by renewed wrestling matches. The new formation of a group or its dissolution takes place without religious rites.

Following Turner, B. Meier (2004) applied the concept of liminality to migrants to Ghana’s capital, Accra (p. 43), because “as in the classic rite of passage, this phase of life is defined by ambiguity and unstructuredness” (p. 42). However, many migrants show no inclination to ever give up their urban life. In fact, a large proportion of them are already third-generation city dwellers. A return to the rural villages of origin can also take place after death (if the body or, as its substitute, some soil from the grave and a piece of clothing, is buried in the north). “Thus, the liminal migration phase finds its conclusion in any case” (B. Meier, p. 43).

B. Meier’s attempt to interpret southern migration as a liminal phase fits with information provided by my informant G. Achaw in 1973. A migrant returning from the south (called sage or sagi; English: bushland) meets his friends for a communal meal shortly after arriving at his home village. According to van Gennep, such a meal is a typical feature of the end of the liminal phase and reintegration into the old community. The cohesion and the “we” feeling as a quasi-initiated group is also expressed by the fact that only friends with migration experience are allowed to participate in this meal.

The life of the communitas in the pastoral group and in a southern metropolis have the naming of the liminal environment as “bush” (sagi) in common.

A weaker realisation of the liminal phase for a communitas group is perhaps found in the life within a boarding school shielded from everyday life. The first Bulsa school of this kind is located between Sandema and Wiaga, surrounded by bushland. The pupils’ contact with their parental home have largely been severed, and the parents do not care much about their children’s lives and academic progress. Traditional structures no longer apply to a large degree. The children of chiefs are on a par with the children of wage labourers. Rites of passage on entry to school are only weakly developed. However, at the end of the school years, as mentioned above for other reintegration rites, a communal meal with the killing of animals and an exchange of gifts takes place, very similar to the siinika ritual of funeral celebrations (see chapter…).

5. METHOD AND WORKING TECHNIQUE

The “classical” methods of ethnology, the participatory observation and the interview, were particularly suitable for dealing with this topic. Observation in a participatory form is extremely important for researching rites of passage. However, it is questionable in which way participation is possible, that is not limited to, for example, contributing a sacrificial fowl or paying part of the ritual costs. Although I was often assured by friendly families that I was now a son of the family after knowing all its secrets (e.g., the rites of passage), I do not think I have always succeeded in shedding the role of white stranger (felika) and outsider within Bulsa society. Only two old informants with much knowledge about their traditional culture (L. Amoak and A. Anyenangdu) removed all the boundaries (or limitations) to a white outsider researcher.

Participant observation at the Pung Muning Earth Shrine (Earth Priest Anamogsi in the middle).

I tried to gain the trust of the younger Bulsa in three different areas of life: at school, with the herders in the “bush” (goai), and in the compound (yeri). At the start of my fieldwork (1973), I taught and lived at Sandema Continuation Boarding School. Although I was called felika (white man) and not teacher by the pupils, I gained insight into their manifold problems and experienced their reactions and attitudes towards old traditions and new institutions. For about four weeks, I devoted myself almost exclusively to the pastoralist group of Sandema-Kalijiisa-Yongsa. Strangely, there I was considered a member of the group under study more than at most schools or compounds. I took on small tasks such as driving the cows together and took part in hunting for rabbits, ground squirrels, monitor lizards, and others, and I received the same share as the other group members (e.g., in the allocation of collected berries). Since none of the shepherd boys were Christian or had attended school, my observations and enquiries about their attitudes towards Christianity, traditional religion, school, and others were of great importance.

My residential stays in some Bulsa compounds (Achaw Yeri and Amoanung Yeri in Sandema-Kalijiisa, and Anyenangdu Yeri and Akanming Yeri in Wiaga-Badomsa) enabled {27} the observation of everyday life (baby care, hygiene, child rearing, division of labour, gender role behaviour, contact with neighbouring compounds, taboos in the daily routine, religious activities, and rites of passage).

After my first experiences at school, with the shepherds, and in the compound, my attention increasingly shifted on the rites and customs of the Bulsa. When participating in traditional festivals or ritual acts, I often became a second centre of interest, especially when using my camera and tape recording. However, after participating several times in festivities at the same compound (e.g., at L. Amoak’s or Anamogsi’s), the interest in me as a person had largely diminished, and attention was again directed to a greater extent at the ritual events.

The researcher’s outsider position is not always a disadvantage for their work. Information has often been given to me with the stipulation that it should not be passed on to Bulsa, and a willing host usually falls silent immediately when a guest from another Bulsa section joins in.

The Bulsa who allowed me to participate in rites and sacrifices in their households shall be briefly introduced here:

1. Leander Amoak from Wiaga-Sinyansa-Badomsa (aged about 59 in 1974, married to four wives who bore him nine children). He was forced to attend the first Catholic missionary school as a child, became a Christian, and intended to study theology for a time, but then became a teacher and married his first wife in a Catholic church. After several marriages remained childless, he returned to traditional religion. Until December 1973, he was a drawing teacher at the Sandema Continuation Boarding School. A few years later, L. Amoak became a kpagi (elder) of a subsection of Badomsa. I would like to call L. Amoak not only one of my main informants until his death in 1983, but also the first Bulo to let me participate in all the rites in his family without any restrictions.

2. Chief Asiuk from Wiaga-Yisobsa (polygamously married, many children). Like L. Amoak, he belonged to the first generation to attend the {28} Catholic mission school established in Wiaga in 1927. Most of his sons are Catholic Christians; among them is the Bulsa’s first Catholic priest. My participation in offerings and the dressing of a house tanggbain was made possible through the mediation of his son, Clement Assibi, who was a student at the Wiaga Middle School at the time. Clement Assibi also introduced me to girls who were ready to tell me about their excision.

3. Anpan Achaw from Sandema-Kalijiisa-Yongsa (polygamously married, six children). He used to attend Presbyterian services frequently on Sundays and is still quite friendly towards Christianity. Anpan did not object when one of his wives became a Christian as Kalijiisa’s first woman who was not a schoolgirl at the time of her conversion and has been actively involved in the Presbyterian parish ever since. Anpan, the head (yeri-nyono) of Achaw Yeri, lived with four brothers, three of whom were Christians. His brothers, Godfrey Achaw and Norbert Achaw, have served me well as informants, translators (Godfrey), and mediators (Norbert) during my interviews in Yongsa.

4. Asekabta Ayieta from Sandema-Abilyeri, with a residence in Suarinsa (polygamously married, many children). Asekabta, a son of the late Sandema chief Ayieta, had never been a Christian and did not attend school. However, he was a great admirer of the Catholic missionaries in Wiaga and did not object to his son Robert becoming a Catholic and taking up a leading position in the Catholic youth movement. Asekabta allowed me to participate in the pobsika rites (cf. chapter II, 4) of his son Robert, who is still one of my most efficient assistants at the time of writing (2023).

5. I have known Anamogsi Anyenangdu from Wiaga-Badomsa-Sinyansa since 1973, when Leander Amoak and I visited his family. Since 1986, I spent all my stays in Bulsaland at his compound, where I had complete freedom of visiting all rooms without asking for permission. He regarded me as his eldest son, and in Wiaga and elsewhere I was known as Anamogsi Felika (Anamogsi’s white man).

Almost all the Bulsa listed above had contact with the European culture or Christianity; therefore, their attitudes towards religious acts do not reflect the average attitude of non-Christian Bulsa. Often their attitude showed scepticism towards traditional religion, which was sometimes connected with the attempt of finding new explanations for well-known {29} phenomena or to create syntheses between the traditional and European culture.

For example, Asiuk, the chief of Wiaga, explained to me that the Bulsa build shrines (bogluta) to their ancestors so that they do not forget their names. The Europeans would not need bogluta for their ancestors, as they could write down their ancestors’ names. The bogluta therefore corresponded to the books of Europeans.

However, the most frequent anachronisms and linguistic neologisms were made by my first main informant, L. Amoak. For example, he refers to the knobbed ma-bage clay pot as a scabies-pot, to the earth (teng) taken from a tanggbain (Earth sanctuary) and kept in the compound as sub-teng, and to the bogluta of his ancestors Ayarik, Agbana, and Adachoruk as Ayarik and Co. He interpreted the three clay balls of the wen-piirika celebration – half jokingly – as embodiments of God the Father, God the Son, and the Holy Spirit. However, it should not be overlooked that the same L. Amoak was considered an expert on ritual disputes among non-Christian Bulsa, perhaps precisely because he applied his exactitude, influenced by European education, to traditional religion, asking himself questions where perhaps others saw no problems and eagerly absorbing all the explanatory possibilities that might arise from traditional religion.

Not only all the young Bulsa, but also nearly all the house owners (yeri-nyam, pl.), agreed to be interviewed. It would have been impolite to refuse a guest’s request after a ceremonial greeting and receiving a gift. Often, however, the interviewee could remember almost nothing, did not know where his father’s bogluk was, or asked me to come back another time. The following types of questions, among others, seem to be particularly sensitive among the Bulsa. The prospects of receiving a satisfactory answer exist only if a strong relationship of trust exists between the questioner and the interviewee, if the interviewee is very acculturated, or he believes himself to possess great magical power (pagrem, cf. chapter V,1). These types of questions include:

1. questions about property boundaries, ownership of land, and so on [endnote 20];

2. questions about the size of livestock ownership; {30}

3. questions about the names of bogluta (only in Sandema);

4. questions about genealogical descent (especially if descent from a slave is suspected); and

5. questions about conflicts in the house (reasons for founding new houses, moving out, and so on).

Looking back at the group of informants and helpers who gave me important information (also including the younger school graduates, some of whom offered to help me), I cannot identify a uniform motive for their willingness to give information. For some, the opportunity to earn some extra money may have been the deciding factor, while others had a strong interest of their own in the tasks set. When I asked A. Akanbe (Sandema-Balansa) to write down his life story for me, he replied that he thought this task was very interesting, as he had already planned to do something like this. Then he wrote a life story of 120 pages.

R. Asekabta and others had already collected material on the history and customs of the Bulsa before my arrival, and Robert even planned excavations at his ancestor Atuga’s presumed place of residence. Informants cannot be generalised as outsiders to society, as they include chiefs, section elders (kpaga), compound heads (yeri-nyam), teachers, and youth leaders.

In addition to the free or only slightly structured interviews, I made some attempts to ask standard questions to excised girls, with the last questions referring to their attitude towards excision (cf. chapter VI, 6). As expected, the refusal rate was quite high and a real sample was difficult to set up; therefore, the results of this action cannot be evaluated statistically in any way. They are only interesting as subjective, biographical statements from individuals, with no attempt to generalise the statements.

After collecting information on the ritual subjects’ lives, I started incorporating their personal attitudes into the framework of {31} overall biographies. Thus, I asked the circumcised girls to record their life stories for me, and in the course of my fieldwork, increasing importance was attached to collecting individual biographies [endnote 21]. In line with my strong interest in acculturation issues, I limited myself to Bulsa participants with school education. I tried to collect the life stories of all Bulsa secondary school graduates in the Sandema-Kalijiisa-Yongsa study unit. Later, I continued my work in the Cape Coast and Sekondi-Takoradi among young men and women of various occupations and positions. All 33 biographers wrote down their stories in English. To provide the writers with a working guide and to ensure that the information was relevant to my work (rites of passage and education), I provided each biographer with some guidelines. The informant usually wrote their life story in my absence. In a subsequent interview, ambiguities were clarified and the biographer was asked to provide further information about interesting details. In the work presented here, only individual quotations from biographies were used {32} (endnote 22).

After my first fieldwork stay (1972–1974), my stays became increasingly stationary. Until 1984, I spent only part of my research time in Anyenangdu Yeri (Wiaga-Badomsa); from 1986, it became my permanent residence, from which all other work emanated. From there, I was able to observe and document numerous rites with in-depth information, particularly in the immediate neighbouring compounds Atinang Yeri, Atuiri Yeri, Abasitemi Yeri, and Akanming Yeri.

During my one-year stay in 1988–1989, I was able to participate fully in all religious and secular activities of a whole year cycle. During this time, I did not approach people in the compounds with structured questionnaires and did not ask to participate in rituals or festivities. Usually, I had so many invitations to take part in important events that it was not necessary to take the initiative. As Anamogsi called me his senior son, I was obliged to take part in certain events. From sacrifices in which I could not participate myself, I still received a share of meat (cf. also Kröger 2012: 41–42).

When Anamogsi, as Earth priest (teng-nyono), medicine man (tiim-nyono), or elder (kpagi), made a visit with me to other compounds in Badomsa, it was unnecessary to ask the yeri–nyono for permission to participate in rites. “You cannot ask someone [Anamogsi] to perform certain rites and then forbid his son to accompany him,” Anamogsi told me.

In Anyenangdu Yeri, a literate son of the compound head carved the names of the compound’s ancestors in all their shrines so it was easier for me to understand rituals and sacrifices.

The method chosen here of a stationary stay in a compound brought me extraordinarily extensive ethnographic data, not only related to rites of passage but also to many other aspects of Bulsa culture.

6. MODE OF PRESENTATION {37}

In ethnographic monographs, rites of passage are often described in a normative form (e.g., “The members of tribe A bury their dead in the following manner…”). This form of expression is at worst the adoption of an informant’s normative mode of description and at best an abstraction from a set of observations and information.

For the Bulsa, it can be said that their information tends to follow such a normative mode of representation [endnote 23]. Most informants assume that all Bulsa form a ritual unity, and they admit at most small deviations between the descendants of the ancestor Atuga who immigrated to Buluk in the 18th century, the southern Bulsa (e.g., Kanjaga, Fumbisi, and Gbedema; see Kröger 2017, 32–61) and the Kasena-influenced inhabitants of Chuchuliga and Biuk. However, in reality differences in the practice of rites exist not only between the villages of Sandema and Wiaga, both of which call themselves Atuga-bisa (children of Atuga), but often also between the individual households of a single clan section. Sandema, for example, has a developed system of joking relations between individual sections which is unknown in Wiaga in this form, while Wiaga’s complex marriage system (cf. chapter VII, 1a) has no equal in Sandema. In Sandema-Kalijiisa-Yongsa, most houses treat umbilical pain in infants through umbilical incisions, while in some households of the same lineage and subsection, such incisions are strictly forbidden.

The informants’ habit of a normative mode of presentation, which often generalises and transfers special rites and customs of their own section to the Bulsa in general, is not only motivated by consciously or unconsciously emphasising the ritual unity of all Bulsa. Many informants display great shyness or modesty in relating their own ritual experience. Perhaps this behaviour also stems from the fact {33} that they think the foreign researcher is only interested in the tribe and their desire to make his work easy. Therefore, it is not surprising that girls who have been asked to give a detailed personal account of their circumcision begin their explanations in the following way: “When you go to excision…”. It does not matter whether the informants give their account in Buli or in English (Fi dan a cheng ngarika ... lf you are going to excision …).

It has already been pointed out that the generalisations from indigenous informants must be treated with the greatest caution. Therefore, it can only be the task of the researcher, if they cannot gather everything through their own observations, to collect biographical material in interviews or through written reports by having the informant describe rites and other actions that they have experienced themselves in all details. The ethnographer’s desk work could only begin with the largest possible collection of individual reports. Usually, this work will consist of critically examining sources, eliminating implausible statements, and arriving at a certain norm for a certain area through comparisons, even if variations and minor deviations remain.

The path traced here will only be partially followed in this work. Although untrustworthy, blurred or less meaningful sources were eliminated for the purposes of evaluation. The final step in moving from individual statements to a generalising statement for a particular group (e.g., Atuga-bisa) was often not taken, but individual statements, which occasionally even contradict each other, remain as source quotations. The justification is partly that I have information about rites of passage from only about 30 of the more than 170 Bulsa clan sections and thus a generalisation would be questionable. An attempt will be made here to give the reader greater insight into the working methods used and their individual results {34}.

This insight might be particularly profitable for other anthropologists and ethnographers, specifically those interested in one topic, since further work on the same or similar topics is thus facilitated and errors are easier to retrace to their origins. Thus, the form of presentation chosen here could also be a compromise between an announcement of the highly summarised, annotated results of field research and a publication of the fieldnotes themselves, which has sometimes been demanded.

Finally, when discussing the presentation form chosen here, with its many biographical accounts of experiences and subjective statements by the informants, one of the aims of this work should be pointed out once again, namely, not only describing rites but also attempting to capture the impact of traditional rites of passage on the lives of young people and their reaction to these rites {35}.

ENDNOTES

INTRODUCTION

1 A guide to the sowing and harvesting time was given to me in the form of the Ghanaian-German Agricultural Development Project Northern and Upper Region’s Crop Production Guide Handbook for the Extension Worker (Tamale, 1974). The Bulsa indicated that their sowing times are usually slightly ahead of those recommended in the handbook.

While the Bulsa often sow after the second rain shower, agriculturists advise waiting until the surface of the soil is about one inch soaked.

2 The Buli expressions quoted in this work from before 1992 were largely obtained through my own enquiries. Some were taken from the vocabulary card index of the Presbyterian Mission Sandema and others from the Dictionnaire Buli-Français by L. Melançon and A. Prost (Dakar 1972). After 1992, my Buli-English Dictionary was essentially my only reference source.

3 The compound forms thus approximate the type described by K.B. Dickson as the “Kusase house type” (Dickson 1971: 127). H. Baumann classifies the roof terrace house in the Old Mediterranean cultural stratum and the conical roof house in the Old Nigritic cultural stratum. Cf. H. Baumann, R. Thurnwald, D. Westermann, Völkerkunde von Afrika (Essen, 1940: 70, 340 and 350). Many Bulsa have assured me that houses with flat roofs are older among them than conical roof houses. These dwellings, and houses with zinc roofs, are tabooed as modern forms in some areas of Bulsaland (e.g., in Kalijiisa-Anuryeri).

4 See the site plans in chapter V,4b.

5 Bulsa with knowledge of English call them towns. The word “city” in the sense of a “big city” is often used ironically for Bulsa villages and towns (tengsa; e.g., Gbensco City for Gbedema).

6 The clan sections’ area units and the administrative districts of a kambon-naab are not congruent. Wiaga-Badomsa and Kubelinsa together have only one kambon-naab, while Wiaga-Chiok has two kambon-nalima.

7 M. Fortes, The Web of Kinship among the Tallensi, Oxford University Press, 3rd ed. (London 1967), p. 64. According to Fortes, two or more domestic families may also live in a single compound, with each domestic family having its own entrance.

8 Not included in my table is a house in Kalijiisa Choabisa where only two women (sisters) from Yongsa live. It is rare for only women (with their children) to live in a compound, but I know of at least two other cases. These are widows who did not want to stay in the compound of their late husband’s parents.

9 Types B, C, and D belong to the joint family here.

10 The same figures were also used in chapter V {p. 183ff. and 185f.}.

11 Cf. R. Schott, Bibliographic Note on the Ethnographic History and Language of the Bulsa (Builsa) in Northern Ghana (unpublished manuscript), Münster, 1974. The bibliography was extended by F. Kröger (1992 and later).

12 Sinésé probably means Siniensi and Bationsé probably means Bachonsi (Bachonsa). Cf. also R. Schott, 1970: 87 (footnote 5). According to my own inquiries, Boura is the Kasena term for Bulsa.

13 L. Tauxier uses the term dot in his work Le Noir du Soudan (1912), which must be translated as “dowry”. However, it is clear from his remarks that he means a bride price.