1. BULI TERMS USED IN THIS STUDY

(A selection)

akpeteshi (Akan): liquor (brandy) made from palm wine

baano, baana, pl. baanoba: diviner, fortune teller, soothsayer

bia-kaasung: miscarriage

biik, pl. bisa: child, dependent person, follower

biisa lika: closing of the (female) breasts (ritual on the second day of the Juka funeral)

bogluk, pl. bogluta: shrine of a supernatural being that receives sacrifices

bogsika (syn. cheesika): gathering food before the Juka funeral

bogta: fibres

bogta: wild plants, leaves used for soups

bolim: fire

boom/ buoom: braided cord around the wrist of a mourner

boosuk / buoosuk: ceramic grave cover

boosuk juroa (joroa): leader of a funeral, (also imitator?) , cf. juem-suroa

bui: granary, grain store

bumbota /sing. bumbook: edible tubers from the scrubland

buntuem (syn. tuntuem, tintuem): ash

busik: Bulsa basket with round opening and square bottom

cheesika (syn. bogsika): gathering food before the Juka festival

che-lie: woman who wears the clothes of a deceased person at his/her funeral and imitates him/her in short dramatic scenes; imitator, impersonator

cheng: ceramic soup bowl

cheri-cheroa: imitator (impersonator) at a funeral ceremony (usually a woman)

cheri saab: special millet porridge that is served, for example, to the wall of the compound

cherika or cheri deka: imitation of the deceased man or woman by a woman

chiaka: literally snatching; institutionalized food theft at a funeral

chichambisa: sons-in-law, they visit the mourning house on the 4th day of the Kumsa funeral

chiik, pl. chiisa: soul, spiritual component that can leave the body (often at night)

chilie: ceremonial female leader at a funeral

chin: calabash bowl

choro(a): husband

daam, pl. daata: millet beer, pito

da(a)ung: body dirt (real or spiritual)

dabiak: courtyard of a residential area

dachoruk: spade, used for digging a grave

da-goong: iron pipe for firing fireworks

dai: day

dalong, syn. kpilima dok: “ancestral room” in the courtyard of the 1st wife; the adjoining room is the dayiik

daluk: red clay for body painting (also engobe of ceramic pots), syn. junung

daluk-saka: painting of close relatives with red clay at a funeral ceremony

dambuuring: name of a tree (Gardenia erubescens), see Juka funeral celebration

darika or Kuub darika: announcement of a death case

daung: dirt (pl. daungta often with sing. meaning), filth, “sin” (e.g. adultery, cf. kabong n. ), esp. moral or ritual offence

dayiik: see dalong

doglie: maid servant of a married woman from her family; she may later marry the wife’s husband

dok, pl. diina: 1. a roundhouse within a building complex, “room”, also: segment of a lineage; . quarter of a woman enclosed by walls

dung: four-legged mammal; in a narrower sense: cow, sheep, goat, dog

gaab, pl. gaasa or gaa, sp. tree, ebony tree (Diospyrus mespiliformis)

gaasika: a particular ritual (including eating from a calabash that has circled the body)

garuk: robe, gown, smock

ginggaung, pl. ginggana: large cylinder drum

golung: triangular cloth apron men

guka: burial (of a corpse)

guuk, pl. guuta: no longer inhabited, ancestral site; hill, mound

guri, pl. gue: wooden hammer, mallet

gbanta: divination, fortune telling, soothsaying

gbanta dai: 3rd day of the 1st funeral celebration

gbieri: to joke, to insult jokingly (institutionalized custom)

jaab, pl. nganta: thing, animal, living being (also used for humans and spirits)

jadok: supernatural being, usually manifested in animals; receives sacrifices on a clay shrine

jianta: tiredness, fatigue, exhaustion

jom suka: putting on the widow’s ropes

juem-suoroa (juem-sieroa): female leader of a funeral ceremony

jueta soka dai, syn. nyaata soka dai (day of the bath ), 2nd day of the Juka celebration

Juka: see kuub juka (2nd funeral celebration)

junung: see (syn.) daluk, red clay

kaabi: to sacrifice

kaam: liquid spice, water filtered through the ashes of burnt millet stalks

kabong: a particular type of adultery (sexual intercourse with a man from the husband’s lineage)

kali kum zuk: to perform a funeral celebration

kaliak: unexcised girl, young girl or unmarried woman

kalika (dai): First day of the first funeral ceremony (syn. kuub kpieng dai; taasa yika dai)

kambon-naab: subchief, the office was probably introduced by the British

kamsa: bean cake (see also koosa)

kikerik, pl. kikerisa: invisible spirit; some of them serve as talking fairies for a diviner

kikiruk, pl. kikiita: person possessed by this spirit, often with deformities

kisi: to hate, to be forbidden, to be taboo

kisuk, pl. kisuta: taboo, forbidden thing or action

ko, pl. koba: father, pl. also: ancestors

ko-bisa: literally children of a father, relatives of one’s own line, often neighbours, cf. ma-bisa

koalin teka: the giving of goods, inheritance

kok, pl. kokta: spirit, ghost, kok is dangerous to living people

koosa: fried bean cakes (see also kamsa)

kum (v.): to mourn, to weep (after the death of a person)

kum-biok: evil death

kum-yiila: mourning song, lament; also: procession of the elders

Kumsa, Kuub or Kuub-Kumsa: first funeral celebration

kurupaani, krupaani: particular spirit

kusung: wall-less common room in front of the compound for meeting guests etc.

kusung-dok: like kusung, but with walls

Kuub: funeral celebration

Kuub darika: announcement of death

Kuub Juka: 2nd funeral celebration for a deceased person

Kuub Kumsa: 1st funeral celebration for the dead

Kuub kpieng dai: first day of the first funeral celebration

kpaam: (originally:) shea-butter, shea-oil (cf. jigisidi n.), (mod.:) general name for any kind of fat, oil, grease

kpaama: germinated millet (for making millet beer)

kpaama ngabika (brewing millet beer): 1st day of the Juka celebration

kpaata or kpaam-tue dai (kpaam, pl. kpaata: shea butter, tue: beans), 3rd day of Kumsa

kpagi: elder, overseer, leader, most senior person

kpagluk: specific animal sacrifice at a funeral celebration

kpalabik: earthen bowl for eating solid food

kpi: to die

kpiak-gebik: chicken killed by tearing or cutting (ritual)

kpilima: ancestors

kpilima-dok: see dalong

kpilung: realm of the dead

kpingsa: orphans

kpio: dead person, corpse

lakori: a principle of following rites and other actions of the past

leelik: war dance, leelik-dai: second day of the first funeral celebration

lie, pl. lieba: daughter, unmarried woman

lig nansiung: literally closing the door (gate), one of the last wedding gifts to the bride’s family

lok, pl. lokta: quiver

ma, pl. maba: mother

ma-bage: female ancestral shrine in the form of a knobbed vessel filled with earth

ma-bisa: literally children of one (a) mother, lineage segment (smaller than ko-bisa)

miiga: tongs; miiga funeral service: special funeral service for a blacksmith

miik, pl. miisa, cord, waist string

miisa folika: taking off the body cords (4th day of Juka)

moolingka: speech(es) on the 2nd day of Kumsa

naapierik ginggana: war dance-like dance to the garbage pile (tampoi)

Naawen (naab wen): God, God in heaven

nabiin(g)-soruk: special necklace with red-white-blue rosetta beads

nagela: Bulsa dance

nansiung: main entrance of the compound

nansiung lika: closing the entrance (ritual after wedding, connected with gifts)

nang-foba: bloodless killing of animals to accompany the deceased to his afterlife

nang-foba tabika: (ritual) stepping on the dead nang-foba animals

nanggaang, nang-gaang: back part (or back wall) of the compound, place behind the compound

nangkpieng: cattle yard within the compound, usually with granaries

Naawen: sky god, often equated with the Christian God

ning-doma: leprosy

nipok tiim: shrine to prevent wives from running away

noai-boka: oracle of the death mat to find out the guilt of the death of a deceased person

nong: friend (opposite sex), lover

nga-nub, pl. nga-niima: mother-in-law

ngarika: burial of a deceased person in a foreign country by material objects (cloth, figurines..)

Ngomsika, Kuub Ngomsika or (Kuub-) Juka: second funeral celebration; ngomsi = to scratch

ngmain: to return (of babies after their death)

ngmiena (pl.): elephant grass, stalk of sleeping mat

nyagi: tribal mark

nyaata soka dai, syn. jueta soka dai (day of bathing): 2nd day of Juka celebration

nye: to make, nye kum: to perform a funeral ceremony

nyiam, pl. nyaata: water

nyiinika: (ritual) purification by smoke

nyono, pl. nyam: owner, person in charge, also used for father

nyuvuri, (pulsating) life

pagrim, pagrem: power, life force

parik-kaabka (parik= wall, kaabka, sacrifice), offering to the outer compound wall at funerals

pielim: open space in front of the compound

piisim: smell of the dead (dangerous)

poali: leather bracelet or hip ring with medicine

pobsika: ritual ash blowing and marking of bodies and buildings with ash, e.g. after birth

poi-nyatika: announcement of a woman’s first pregnancy

pok, nipok: woman, lady

pok-nong: married woman, the (platonic) girlfriend of another man

pokogi: widow, widow’s string

ponika: haircut of the head

Pung Muning (literally “red rock”): tanggbain of Badomsa, owner: Anamogsi

púúk, pl. púúsa, belly, pregnancy (syn. logi)

pùùk, pl. púúta: specific ceramic pot with lid, see also ma-bage

puuta mobika or puuta cheka: destruction of ceramic vessels of a deceased married woman

saab, pl. siira, millet porridge, T.Z.

sa-gaang: unfermented millet porridge, often prepared by men

samoanung: large round earthenware vessel for cooking

sagi (goai): bush

sakpak: witch, sorcerer

san-yigma (san-yigmo): matchmaker (intermediary), who later also performs other (ritual) tasks

sapiri: stirring stick, especially for millet porridge

segi: the guardian spirit bestowed on a person at a segrika

segrika: ritual act; offering of a child to a shrine, also naming of a child

sinlengsa / senlengsa: double bell

sinlengsa (senlengsa) dai (day of double bells), syn. daata nyuka dai (day of pito) 4th day of the Juka funeral celebration

siinika (literally, stacking): ritual distribution of gifts at a funeral

siira manika dai: 3rd day of the Juka funeral celebration

sinsanguli, pl. sinsangula: basketry rattle; accompaniment to women’s chants at funerals

suma: round beans, “Bambara peanut” (Voandzeia subterranea)

suurika: ablution, purification (ritual and secular)

taasa yika dai: first day of the first funeral ceremony (syn. kalika).

tampoi: garbage heap, ash heap in front of the compound

ta-pili: (rolled up) death mat

tapili-yika: hanging up the death mat shortly after death

teng: earth, earth spirit, earth sanctuary, village, land….

tanggbain, pl. tanggbana: earth shrine of a particular ritual district; often: a grove, river, tree, rock

teng-nyono, pl. teng-nyam: sacrificer of the earth shrine, earth priest

tiak, sleeping mat

tibiik, pl. tibiisa: ceramic vessel for liquid medicine

tigi: group of people, gathering, festival of secular character

tiim: medicine, medicine shrine, amulet…

tiim-nyono: medicine man, “native doctor”

tika-dai (gathering day): second day of the first funeral celebration (syn. leelik dai)

tintankori, pl. tintankoa: round stone of a male ancestral shrine, residence of the wen

tom, bow (weapon)

tue (pl.): beans

vaata: leaves, leaf clothing of a woman (in the past), also used for fibre aprons

vayaam, vaam: medicine of the gravedigger, medicine against the smell of the dead, ghosts, etc.

vayiak, pl. vayaasa: gravedigger

vorub, hole, grave shaft

wen: fateful, divine power, receives sacrifices at a shrine , destiny, fate

wen-piirika: in this ritual, an individual’s wen comes from the sun and is worshipped in a shrine (bogluk) ever since

wie-wie: literally ‘words-words’; ornamental scars

wuuling, weeling: ululation, trill (applause of women)

yaba: market, market day (usually every 3 days)

yeri, pl. yie: compound, larger lineage (as opposed to dok, smaller lineage), clan

yeri-lie: “daughter of the house”, matrilineal relative of the yeri-nyono

yeri-nyono, pl. yeri-nyam: head of a compound; man of greatest seniority (not always highest age) within a compound

yiili, pl. yiila: song

yulimka: circular movement (e.g. of the hand) before an execution

zangi: vertical rod or pole

zangni bobka: to tie an animal to a pole (ritually)

zom: millet flour

zo-nyiam (zu-nyiam): millet water (drink)

zong-zuka cheka: drumming on the flat roof near the entrance of the compound (at a funeral)

zuka: burning (e.g. of the funeral mat)

zukpaglik: neck support made of wood, “pillow”

zutok: cap

zutok muning: red cap (e.g. of a diviner, mourner, chief etc.)

2. ABBREVIATIONS

fn: Author’s field note with year and card number (collected on marginal hole cards).

Fb: Field book with original field notes

F.K. (fk): Franz Kröger (author)

Indicating a genealogical position:

F= father

M= mother

S= son

D= daughter

B= brother

Z= sister

H= husband

W= wife

3. INFORMANTS AND ASSISTANTS

3.1 Godfrey Achaw (from Sandema-Kalijiisa-Yongsa, Achaw Yeri)

Godfrey Achaw and Franz Kröger (2005)

The collaboration with Godfrey was already decided in Germany before my first arrival in Ghana, because 1967-68 he had already been the main assistant of my doctoral supervisor, Prof. Schott. In 1972, he worked as a nurse at the hospital of the University of Cape Coast. At the same university, I was to set up a German sub-department within the Department of French from 1972 to 1974. My German courses were also attended by Godfrey and other Bulsa.

Through Godfrey I expanded my basic knowledge of the Bulsa. He introduced me to the Buli language and provided me with the first data on their rites of passage.

It was also important for me that he introduced me to all (12?) Bulsa living in Cape Coast. Of these, some are particularly worth mentioning: Ayarik Kisito from Wiaga-Tandem-Zuedema, in whose family I was able to observe and document umbilical incisions. Akoasisi from Siniensi and Adama from Wiaga-Chiok were also very helpful in providing me with information. The connection to Adama remained when I took up residence in Wiaga. In Anduensa Yeri, his father’s compound, I underwent the vayaam rites of a gravedigger.

With Godfrey Achaw, I made my first trip to the Bulsa area in my Volkswagen, where he introduced me to his home section of Kalijiisa-Yongsa. I stayed in his and his brother’s compound, Achaw Yeri, for a short time, and for a longer time in Amoaning Yeri, whose head, Apatanyin, was also a willing informant. I conducted my first real fieldwork in the 21 compounds of Yongsa. When I shifted the focus of my work to Wiaga-Badomsa, my cooperation with Yongsa diminished considerably.

Godfrey was later (1979?) doused with petrol by soldiers of a military government and set on fire. He only narrowly escaped death. Afterwards (1979), he unsuccessfully applied for a parliamentary seat for the Action Congress Party and later emigrated to the USA. After his return, I met him only once in 2005 in Sandema, without any further co-operation.

He died in Ghana on 20 April 2013.

3.2 Robert Asekabta (from Sandema-Abilyeri) and other informants from Sandema

Robert Asekabta

Robert approached me at the Sandema market; he wanted to work for me. Even though he did not become my permanent assistant, we were able to successfully complete a number of projects. For example, we compiled the genealogy of the Sandema chief with over 1000 names. I also observed and documented my first Segrika ritual in his father Asekabta’s house. Later, I only occasionally consulted Robert for information on rites of passage and linguistic problems. For example, he was an important co-editor of the Buli Language Guide. When I was no longer able to travel to Ghana after 2013, he became my most important contact person, as he was the only one of my former surviving helpers who could be reached via email and Messenger.

I was only able to acquire limited data from other Bulsa in Sandema, e.g., from the compound heads in Yongsa. Unfortunately, I did not find an informant who, for example, as a compound head, gave me unrestricted access to all rites and his secret knowledge, as was later the case in Wiaga with Leander Amoak and Anamogsi Anyenangdu.

My occasional informants in Sandema also included Azantilow, Sandemnaab and Paramount Chief of all Bulsa. Perhaps even more important than his information was the fact that he held his protective hand over me in all external crisis situations (e.g., with police authorities).

3. 3 Leander Amoak and Danlardy Amoak (from Wiaga-Sinyansa-Badomsa, Asik/Adeween Yeri)

Leander Amoak

As I initially wanted to do my doctorate on the subject of “intergenerational conflicts”, I felt that close contact with the younger generation was necessary, and this was probably best achieved in a school. That is why I taught at Sandema Continuation Boarding School during the 1973 and 1974 university holidays with a limited number of hours per week. There I met the art teacher, Leander Amoak, who had also occasionally given information to Prof. Schott. When one day he invited me to take part in the transfer of a female ancestral shrine (ma-bage) he was probably a little in doubt about whether my participation aroused the ancestors’ anger. So he forbade me to take photos a few days before the event. However, when I arrived at Asik-Yeri on the day of the ritual, he permitted me to use my camera and tape recorder without any restrictions. As kpagi of the Ayarik-bisa lineage segment and one of the first literates in Badomsa who readily assisted others in dealing with administrative authorities, he commanded great popularity and authority, and he and I could hardly be denied any information.

Apart from visiting and documenting most of the rites of passage in Asik Yeri, we also visited all 21 compounds of Badomsa where we took a census and a record of all the important ancestral shrines. The result was published in my book, Ancestor Worship among the Bulsa (1982).

After Leander’s death (on 30 August 1983), I tried to continue my work with his family and approached his eldest son, Danlardy Leander, a primary school teacher and later headmaster of the Arabic School Wiaga, with my unanswered questions. Danlardy had neither the authority in Badomsa nor as much knowledge of traditional culture as his father. He mainly served me as an interpreter during compound visits and transcribed and translated numerous Bulsa texts from my tape. Like his father, Danlardy did not live in Asik Yeri, but in Wiaga-Goansa (centre) where he died on 24 October 2022.

3.4 Anamogsi Anyenangdu (from Wiaga-Sinyansa-Badomsa, Anyenangdu Yeri)

Anamogsi Anyenangdu

Leander’s actual successor in my research work was Anamogsi, the earth priest (teng nyono) of Badomsa, kpagi (elder) of the Badomsa-Abadomgbanabisa lineage segment, compound head (yeri nyono) of probably the largest compound in Badomsa and owner (tiim-nyono) of the birth medicine biam-tiim, which is known beyond the borders of the Bulsa region. When I asked Leander to name a traditional compound in Badomsa where I could stay for a longer period of time and where I would be allowed to participate in all the traditional rites with permission to take photographs, he replied: “Choose one of Badomsa’s (over 50) compounds yourself; they are all ready”. My choice fell on Anyenangdu Yeri, and I have never regretted this choice. In this compound, I and all my European and African visitors had completely free access to all rooms and activities. As the lighting conditions in the windowless ancestral room (kpilima dok) were quite poor for taking photographs, I was allowed to take important shrines and other ritual objects out into the courtyard for this purpose.

After he adopted me as his eldest son, there was even a certain obligation to take part in all sacrifices and other sacred acts. It was very important for me that I was given an explanation of every detail I didn’t know in several sessions afterwards. Of course, there was also absolutely secret knowledge that Anamogsi was not allowed to share with me and his “other” sons. I liked the fact that when I asked him about this, he didn’t try to satisfy me with excuses or false answers (as was usually the case), but instead clearly explained, “I’m not allowed to say that”.

The most important thing for me was that I could move around almost as freely in the three houses of the ko-bisa (Atinang Yeri under Atinang, Atuiri Yeri under Ansoateng and Angoong Yeri under Atupoak) as I could in Anyenangdu Yeri. The other Badomsa compound heads could hardly refuse to give Anamogsi’s eldest son any information. When Anamogsi told me about our visit to a ngarika burial in Badomsa, in which he himself played a leading role as kpagi, I wanted to buy some kola nuts and a bottle of Akpetishi for the compound head and the gravediggers. Anamogsi just laughed and said, “They have to give us gifts because we are the chief performers at the burial”.

Anamogsi was illiterate but very interested in technology. He drove my moped and operated my tape recorder at tanggbain sacrifices so that I could concentrate on the photos.

He died in 2010 at the ripe old age of about 85 (?). After that, I continued to live in Anyenangdu during my research visits. Under Asuebisa, Anamogsi’s son and successor, who himself had belonged to a Christian sect for several years, nothing had changed in terms of my freedom of movement in the compound, my possible participation in rituals and their willingness to obtain information.

3.5 Akanming Awasiboa (from Siniensi, resident in Wiaga-Badomsa until 1994)

Akanming Awasiboa

About half a kilometre from Anyenangdu Yeri was Akanming Yeri. Despite his origins in Siniensi, which can be traced back to the change of residence of one of his ancestors several generations ago, Akanming was regarded as an expert on all of Badomsa’s internal affairs. As a recognised diviner, he even received customers from outside the Bulsa region.

Although I was also able to observe sacrifices to ancestors and the Pung Muning earth shrine, as well as numerous rites of passage in his compound, Akanming was my most important informant on divination, which permeates all areas of religious life among the Bulsa. Particularly in numerous wen-piirika rituals, which are almost exclusively performed by diviners, I learned about possible variations of this ritual during our visits to other sections. Akanming made sure (especially in 1988-89) that I was never absent from any of his wen-piirika rituals because he had a plan to make me a diviner myself, as none of his many sons were interested in this profession. To this end, he gave me special lessons with his own divinatory set, and I had to take on smaller tasks when he visited other sections.

Shortly before his death on 28 July 1994, Akanming moved back to Siniensi (January 1994), where he took over a larger compound as a yeri-nyono.

3.6 Yaw Akumasi Williams (from Wiaga-Yisobsa-Napulinsa, Apok Yeri)

Yaw Akumasi

Yaw was not one of my most important informants, but he was almost an ideal helper for the various tasks of an ethnologist. As the son of Anamogsi’s eldest daughter, Akawai, he knew everything about Anyenangdu Yeri, where he had also lived with his mother for several years. He did not only know a lot about all the rites of passage, but also tried his hand at analyses and rational attempts to explain these rites. The Lakori concept, which plays a role in the establishment of ritual changes, was developed by him and me.

At large rituals, for example, funeral celebrations, he took on the role of a second ethnologist who collected data with a second camera and tape recorder at other locations in the compound when I was unavailable at another location.

After Alfred Agyenta, the later bishop of the diocese of Bolgatanga/Navrongo, he was also the most important collaborator in the creation of a second revised edition of the Buli-English Dictionary, which was published as an app (“Buli-Dictionary”) for smartphone devices (in 2021). When I spent three weeks in Accra in 2012 without a northern Ghanaian stay, he came to Accra, devoted many hours to revising the dictionary and did completely independent work in the National Archive of Ghana searching for and photographically reproducing texts about the Bulsa.

Much of his help was not of an ethnological nature, but was often a prerequisite for my research. In 2011, for example, he made it possible for me to travel to the Koma as a passenger on the back of his motorbike, whereas I had previously travelled with him by lorry (2002, 2005 and 2006) or bus (2008) to that area.

When a German television crew documented my ethnological work among the Bulsa, Yaw took on the role of microphone assistant (2005) to the complete satisfaction of the film experts.

Having joined the Restoration Power Chapel Wiaga early on, Yaw worked there as a preacher and later as a pastor and leader. After my last stay in Ghana, our collaboration was, to my great regret, limited to a few phone calls and letters, as Yaw could not be reached by e-mail.

3.7 Margaret Arnheim, née Lariba Bawa (from Gbedema-Gbinaansa, Akanwari Yeri)

Margaret Lariba Bawa (1981)

My informants have so far consisted exclusively of male Bulsa. Women usually leave their parental home at a young age (sometimes already as children) to marry into a foreign compound, where they are regarded as strangers who are usually not given a detailed insight into the religious secrets. Nor do many women seem very interested in giving a foreign researcher an insight into their personal lives and the rites that accompany them.

When I taught at the Sandema Continuation Boarding School, I tried to close the existing gaps in intensive discussions with older female students. I was only moderately successful. It was particularly difficult to collect data on linguistic problems. However, there was one exception. The former student Margaret Lariba Bawa (later Margaret Arnheim) became one of my most important informants and collaborators.

During my research visit in 1978, Margaret, who had since trained as a nurse, told me that she would like to come to Germany. As both Prof. Schott and I urgently needed Bulsa collaborators in Germany, I replied to her with the stereotypical sentence that I had already said to many others: “If you pay your own air ticket and are prepared to help us with our Bulsa studies, you are very welcome”. At the beginning of December 1979, I received a surprise phone call from Mrs. Schott (Münster) to say that Margaret had arrived with her family.

Both Prof. Schott and I immediately recognised her extraordinary linguistic talent. She spoke four languages perfectly (Buli, Twi, Hausa and English) and, after a relatively short time, also German. While Prof. Schott urgently needed help with transcribing and translating audio tapes, I needed a native speaker to edit a Buli-English dictionary. I was surprised not only by her good knowledge of Buli, especially her competence in determining the Buli pitches, but also by her tirelessness and perseverance. We often worked many hours into the night without interruption.

As Margaret was born in Accra and only moved to Gbedema with her parents to attend the Boarding School at Sandema, I didn’t expect her to have much knowledge of general cultural issues, especially in the religious sphere, but here too I was surprised. Although she converted to the Catholic faith as a child, she showed a great interest in traditional religion, and through her constant questioning of ritual events, she was able to acquire very good knowledge, which is extraordinary for women. The data I collected in 1973-74 on rites of passage and which I published in book form in 1978, was therefore richly supplemented.

3.8 Bulsa Facebook groups (Bulubisa Meina Yeri, Buluk Kaniak, Buluk in Focus and others)

It seems unusual to include Facebook groups in a list of Bulsa informants. But especially in the groups mentioned above, I was able to gather valuable information about rites of passage that I had not known before. The groups are mainly frequented by educated Bulsa, who often do not know very much about the traditional life of their ethnic group, but are nevertheless (or therefore) very interested in it. However, there are some academics who have a very good knowledge through their early experiences in a traditional compound or by gathering information (see Kröger 2022).

Another method of data collection was that I asked questions to the Facebook groups myself. Most of the time they were not answered completely without any results. If the questions became too intimate or general privacy was jeopardised, I asked very specific questions to one of my 5,000 or so Facebook friends and continued the topics of the public discussions there.

4. GENEALOGIES

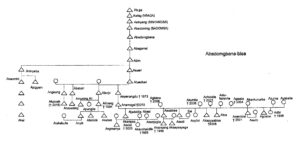

4.1 Genealogy Abadomgbana-bisa

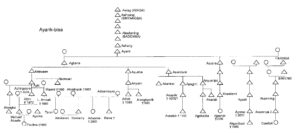

4.2 Genealogy Ayarik-bisa

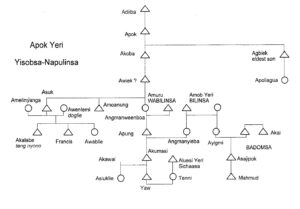

4.3 Genealogy Apok Yeri (Napulinsa)

5. FUNERAL SONGS

Preliminary remarks

The most comprehensive written source for funeral songs are found in U. Blanc’s publication on “Music and Death…” (2000). Her in-depth analyses could only be imperfectly mentioned here. My most important informants were Yaw Akumasi, who sang songs himself on tape and later transcribed and translated the recorded songs, and Akanjaglie from Kanjaga, married in Wiaga-Badomsa.

The Buli statements of the texts are often difficult to understand. On the one hand, this is due to the fact that some songs contain passages in dark Buli (Buli sobluk), and on the other hand, the singers assume that their listeners have a knowledge of many events that outsiders do not possess. In the Buli transcription, some words appear in a less common form (ngiek instead of ngiak, soliok instead of saliuk, yeti instead of yiti…). They appear here unchanged.

Many songs for the dead (kum-yiila) are known throughout Bulsaland, but others can also be invented spontaneously by the precentors. For example, they pick up something from a discussion of the old men in the kusung, or they make fun of the long speeches of the elders.

Most of the funeral songs are sung at the Kumsa, not so many at the Juka. Their performance is not limited to certain days or hours.

The songs sung by women and men are lyrically the same, but there may be differences in the melody. Akanjaglie notes that men’s songs have a faster rhythm and are not as emotional as women’s. . The “aeroplane song” (no. 12), for example, would not be typical of women.

The instrumental accompaniment for men, if any, consists of ginggaung or gori drums, and for women, of sinsangula basket rattles.

The women have three leaders: The eldest of them is their official leader and is also initially named as the precentor who starts a song. She usually passes this task on to another woman with good vocal qualities, and a third woman repeats a text followed then by the rest of the women. Many younger women are afraid of becoming the precentor for fear of witchcraft (fk out of envy?), because the leader is often in danger.

Once a song has started, it cannot be interrupted, even if a death occurs in the compound.

During the three processions of men around the compound several songs may be sung, but no new song may be started until one has returned to the nangkpieng, i.e. up to three songs may be sung in the three processions.

Funderal songs should not be sung outside of funeral celebrations. When Yaw sang songs on tape, some women came to us but said nothing. If children want to sing songs for the dead, they go to a tree away from the house. The taboo doesn’t seem to be very strict, however, because my (later) cook sang the death song “Ti miena nong…” (‘friend of us all…’, cf. Blanc 2000, p. 141ff) for me during my first stay at the Anyenangdu Yeri compound, which in this case meant not a deceased person but me.

No 1

Place and time: Agaab Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa-Chantiinsa; sung on the first day of the Kumsa celebration, 2008

Context: Group of elders with their precentor; transcribedd from the tape recorder

Quoir:

A ga tigsi Yesobsa bisa ga ngiek-ge -eee (They went and assembled, the children of Yisobsa, for the ancestor).

Ayen ba cheng ka ngiek yaba yeti soliuk ga ngiek yaba. (They [the living people] said that he [the dead person] went to the ancestral market, [he] woke up in the morning and went to the market.

Ayen ngiek ge ngiek bo dok teng-ge eee (They [the living people say, ancestor and ancestor [sic] is in the room under the earth [=grave].

Precentor:

Ayen ngiek yaa kpaammu, ate ngiek yaa kpaam ba ([they] said that the ancestor has warned, has warned them)

Quoir:

Ayen ngiek ge ngiek yaa ga togi lang lang eeee (that the ancestor -ancestor has spoken sweetly) [i.e. the dead persons remains under the ground]

Precentor:

Ate ngiek yaa kpaam ba, ate ba le changi la ngiek yaa ga (and the ancestor warned them, and when they went, the ancestor went and warned them)

Quoir:

Yesobsa bisa gbengi diok yaaaaa (Yisobsa’s children are a male lion yaaaa)

Precentor:

Ate ku a nyini bee aaaaa? Ka nna ti ku a nyee? (And where does it [death] come from? Is it so, as it does?)

Quoir:

Eeeeeh aaaaah

Precentor:

Aaa wi yeee eeee aaaa oooo wi yoooo yooo. A ga biisi, Yisobsa bisa ga ngiek eee ([They] went and spoke. Yisobsa’s children went to the ancestor).

Ba yiti soliuk ga ka ngiek yaba. Yesobsa bisa ga yogoo. (They woke up in the morning and went to the ancestral market. Yisobsa’s children went in the night)

Ate ngiek yaa gaa biisi cheng la ngiek yaa ga biisa (An ancestor went and was speaking – as they attended the ancestor [he] was speaking).

Ate ba li yiti la ba cheng ka ngiek yaba (And when they woke up, they went to the ancestral market).

Quoir:

Ayen ngiek ge ngiek boo dok tengee ([I?] said ancestor and ancestor is in the room under the earth).

Ate ngiek yaa ga kpaam ba ate ngiek yaa gaa kpaam moa (and the ancestor has been warning them and the ancestor has been warning)

Ngiek geeee ngiek boo dok tengeee yaaaa (ancestor and ancestor is in the room under the earth)

No 2

Place and time: Agaab Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa-Chantiinsa 2008

Context: Kalika dai: Women singing sinsangula yiila (They blame the inhabitants of the compound, because they did not give them millet water).

Note: The printed songs of this Kumsa celebration (Kalika Dai) provide a short form. All repetitions were left out.

Ba wai wai bani nyiemoo ba wai kan te jaabo (water – none of them gave them [the singers] anything)

Alege ka noin gban po jiam yoo (but [they] gave thanks only with [their] mouths/lips)

ayen amotia dok demma yik ka jaab li nyiila (they said that Amotia [people from Agaab’s room] caught something with horns

waalikaa yeeyeeeee (extraordinarily).

Mi yen Amotia dok demma yik jaab li nyiila (I said that Amotia’s room people caught something with horns)

waalikaa…

Ni nina be nnya ba ya, aiya ababababababa (Your eyes have not seen them [The precantor is addressing the other singers]

Mi yen….

Age ba kan weeni ti Ajaab wommoa ali Akumjogbe (But they should not say that Ajaab [Agaab Yeri] hears this with Akumjogbe.

Apok biik le maa boru wa tengka nyona bi an posima (Apok’s child [Yaw, my assistant from a compound with a teng/tanggbain] is amongst them. He, the teng-owner, is not small)

Age ba ngaangka le kala Kaadem la, bi kan weeni ate wa tue wom yoo (But their back is in Kadema, do not speak that his ears hear)

Ka wie yo , ka wie yo, ka wienga maga maga aaa (It is a problem… it is a small problem)

Mi yen Akubela dokdem yik jaab k(u) an nala (I said Akubela’s room companions caught something, which is not good)

…

No 3

Place and time: Agaab Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa-Chantiinsa 2008

Context: Kalika dai: Women singing sinsangula yiila

Note: The printed songs of this Kumsa celebration (Kalika Dai) provide a short form here. All repetitions were left out.

The pidgeon probably symbolizes the deceased.

Nya m le ko mi nangbang ate baa vara ya wo ya wo (Look, I have killed my dove and they are seizing [it] ya wo ya wo)

Ni yaa bi nya ka daa yeri nyona nangbang-eee (Look carefully. It was not the house owner’s dove).

…

Mi yaa le nyini daa cheng la a yaa ga ko mi nanggbangka (I came out and was walking, and they killed my dove.)

Ate ti baa vari la, mi boa nmaba? (And when they seized [it], what [will] my mothers [say]?)

…

Mi yaali nyini pisi mi nanbenta a cheng a yaa ga pisi mi nangbangka (I wanted to come out to pick up my cowdung and walked and found my dove)

Ti yeni nyono daa vari la. Mi dek ti ndiem nya boa? (Our house-owner seized it. What I should do is “nba” (onom.: free oneself from such a person)

…

Aaya, ka daa yeri nyono nangbanga (No, it is not the house owner’s dove)

Chini nyona jam a chini nyona jam. Ni liema a ngma jam oo? (Calabash owners, come! Your daughters will not come. [Calabash owners are the women at a funeral who are responsible for calabashes and clay pots with water, food etc.; daughters = daughters of the house; they should come and bring [money])

Ta yaa ka ba liema nyini (We want their daughters to come out)

Ba jiammoa yienga nyamma ba jiam yooo (They [= we] thank them [the house-owners] for their thanks)

Mi a nak ba jiam, ba kala kan biisa mi la a nak ba jianta (I am knocking their thank. And they are sitting without thanking [us]. I knock their tiredness)

No 4

Place and time: Agaab Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa-Chantiinsa 2008

Context: Kalika dai: Women singing sinsangula yiila?

Note: The printed songs of this Kumsa celebration (Kalika Dai) provide a short form. All repetitions were left out.

Yaa bi nya bolim de taa yeri kusung (You see, fire burnt our compound-kusung) [fire = death]

Ti ba kala ba cheesi alaa (when they were seated they came together to mock)

Bolimu dee a Wieg yeri kusungoa a tali garuk moan[ung] yaa (fire burnt the Wiaga kusung and left only a red smock [= the remaining people])

Ayen nya bolim dee taa yeri kusungoa a tali garu moan yaa (fire burnt our compound kusung and left only a red smock).

…

Nya bolimmu dee ka Akalinya bis ati ba kala ba cheesi a la (See, fire burnt Akalinya’s [an ancestor’s] children, and they are seated and come together and laugh)

Bolim dee ka a sebwie kusung-oa... (Fire burnt a clever man’s kusung…)

…

Bolimmu bi deê taa yeri kusungoa ale ba garu moanung -oaaa (… with their red smock)

No 5

Place and time: Sandema?

Context: James Agalic’s M.A. thesis. If somebody died people ask: “Wa ta ngaanga?” Has he

children?

Fi dan poom yiak niiga a jo (Even if you possess cattle)

Fi dan poom yiak piisa a jo (Even if you possess sheep)

Fi dan poom yiak bonsa a jo (Even if you possess donkeys)

Ale ka ta nuroa (but you do not possess people)

Fi tin ta boa (you possess nothing; {literally: What do you have?]).

No 6

Place and time: Compound, Atekoba Yeri, Sandema-Choabisa, 17-18 April 1973

Context: Song sung on the first day of the Kumsa funeral by women sitting in the cattle yare near the mat (i.e. by sinsangula women). This song can only be sung by women.

Linguistic and content explanations: Ajuibisa refers to the arriving visitors (Thomas Achaab, Godfrey Achaw and F.K.; Thomas is related to Atekobaa Yeri; fall: he will be miserable; wang: pour away, yariba: scatter about; Ba nag yeni: ……evil-minded people (e.g. witches) will destroy the house after such a strong man has died

Ni kal be ya (3x)

Ajuibisa wa kal be ya (3x)

Wa wa lo.

Ba nag yeni wang yariba yariba (wang= to scatter, yariba= without plan)

Nya, ba nag yeni wang ate ba ta ba la.

Ba nag yeni wang ate ba ta ba ala.

Ba nag yeni wang yariba yariba.

Where will you (pl.) sit (stay)? 3x

Ajuibisa, where will he sit? 3x

He falls (is miserable).

They beat the house into pieces.

Look, they have beaten the house to pieces and they are laughing at them.

They have beaten the house to pieces.

They have beaten the house to pieces.

Nr 7

Place and time: Sandema-Suarinsa, 1973

Context: A shepherd group sang the following funeral song on my tape.

[F.K.: Text and translation are not quite clear, toagri in B.E.D.: to kill an animal]

Aka a tin lam kpiuk,

naabula ka toagri wang naabula yaa toagri wa.

Asangbiok ni wa kan tiri lam kpiuk-oa.

Naabula yaa toagli wa, naabula yaa soagli wa.

I do not touch [tiri] meat of a dead person.

Bulsa stepped on monkey and it poised [was killed?].

Azangbiok does not touch meat of a dead man.

Bulsa stepped on monkey and it poised [?].

Nr 8

Place and time: Sandema Boarding School

Context: Song sung on my tape recorder by girl-students of Sandema Boarding School. At funerals this song is sung at the market.

The song contains a lament about somebody’s deceased brother. The survivor asks Atuga’s Wen to let him live at least one more year, because his brother can harm him.

1. Version (sung by Margaret Lariba [now Arnheim])

N’dek mabiika naa nyemu se ze

Wa tamu taam goiya daasi longsi na wi gbema yigre (2x)

Nya jaab jaab ben gaam me suok-oo (2x)

Atuga wena maar tin jok paai beiya

N’dek mabiika kaboa, Atuga wena maara

N’dek suok-oa kaboa, Atuga wena maara

Atuga wena maarya, Atuga wena maar tin jok paai benya.

2. Version (sung by Mary Syme from Siniensi)

N’dek maabiik na na nye mu se wa ze

Wa tin tam goi ya daasi lonsi a na wi gbegma yigri (2x)

Jaab jaab kan gaam mi suok-oa (2x)

Atuga wen tin jog maar paari

N’dek seok-oom Atuga wen naa maai (several times)

Atuga wen naa maar tin jog pasi ben ya.

Translation of the second version:

My own realtive is doing (treating) me as if he does not know me.

He took me to the bush and pushed (me) down that lions might catch me

Nothing, nothing is more than my brother [for me]

Atuga’s wen should reach [should not fail to be reached] and help

My own brother, what is wrong?

Atuga’s wen should help me, not to break down (?) [jogi= fail, pasi= break, remove, beni: delay].

3. Version (sung by Margaret Lariba)

N’dek maabiika ala nya mu se wa ze,

Ate mu tanyoai [tan goai?] a daasi luensa ale wa gbegma jig mu

Ja-ja a yom mu n suik

Ja-ja a gom mu n suik ate ba weni maa ate jou [jog?]paa ben ya

N’dek mabiik-aa, ka be ate bu weeni ate suayu ka be ate ba weni maa (3x)

Ate ba weni ma ate yug pau benya.

Nr. 9

Time: 2006

Context: Text provided by Yaw Akumasi

(a) Fi taa nyaa wa be?

(b) Fi taaa nya wa ka chamu ten yaa duesa teng? eee!

Precentor: a, a;

Quoir: a

Precentor: a in a higher voice with longer syllables, a

Quoir: b (repeated at will)

Translation:

(a) Where will you see him?

(b) Will you see him (the dead person) under a shea tree or a dawa-dawa trees? No!

Nr. 10

Place and time: 2006

Context: Text provided by Yaw Akumasi

(a) Fi daa yaali fi yieg fin bonsa a jo, fi yieg [yiagi] niiga a jo

(b) Fi kan ta nuru, fi tin ta boa aaa? (=e)

(c) Ni miena sie yoo

(d) A jog nuru

(e) Fi kan ta nuru fi tin ta boa aaa? (=b)

Precentor: a+b, a+b; c,

Quoir: d+d+e

Translation:

(a) If you like, you drive donkeys in (into the cattleyard), you drive cows in

(b) You do not have a person, what do you have?

(c) You all respond now

(d) You miss a person

(e) You do not have a person, what do you have?

Nr. 11

Place and time: 2006

Context: Text by Yaw Akumasi

(a) Ja-jak biik nya wensie bee?

(b) Ate wa togi wa wani, age ba daa zeri yaa

Precentor: a, a,

Quoir: a b

Translation:

(a) The child of a poor person, where does he see truth?

(b) And he (the child) explains his problem, but they refuse.

Explanation:

When making decisions, one only listens to important (rich?) people. The song calls for listening also to the child of poor people, because death makes everyone equal.

Nr. 12

Place and time: 2006

Context: Text provided by Yaw Akumasi

(a) Afelik nye jaab-o, ate wa ka nangsa, ate wa ka bogi ye

(b) A yaa la giri [= yiti?] wen lab-lab-lab

(c) Yoo-

(d) Nya, felika nye jaab-o ate wa ka nangsa

(e) Alege ka bogi ya a yaa li a yiti wen yaaa

Precentor: (a+b) + (a+b)

Quoir: c+d+e

Translation:

(a) The white man builds a thing (an aeroplane), but it has no legs and it has no wings,

(b) And it rises [roars?] to the sky, lab, lab, lab. (giri: cf. giri-giri: railway).

(c) yoo

(d) Look, the white man builds a thing and it rises to the sky: lab, lab, lab.

Explanation: This song is well known to most Bulsa.

Nr. 13

Place, time and context:

The singer Akanjaglie, a native of Kanjaga, married to Wiaga-Sinyangsa-Badomsa (Anyenangdu Yeri), sang the following songs in 2006 at her late husband Akanpaabadai’s newly established compound on my tape. Many of her songs have a personal reference to her beloved husband.

Precentor:

Kori nummu la nag la n zang we n chib wee – eee

Atingim ma, n zang we n chib we – eee

Nya dila ka yiila, n zang we n chib we – eee

Nya jaamu la vuusi; vusi kaai la n zang wee, n chib wee

Quoir:

Kori nummu la nag nag kai la n zang we, n chib we…

Translation:

The eye of the east (= sun, i.e. the day when the sun rose) beat my zangi (forked post), broke, my chib (roof beam)

Atingim’s mother*, my zang broke, my chib broke

Look, such is a song. My zangi broke…

Look at the living thing, how it is breaking. My zangi broke…

*Atingim is a nickname for Kanjaga; Atingim ma is Akanjaglie; Atingim may be replaced by “Atuga bisa” in other villages, for example.

Nr. 14

Place, time and context: see no 13, sung by Akanjaglie

Precantor

N boro a niek (niagi) ba wienga age ba yen maa kaasi

Jabiak wari boro da-yong-oo

A de yee yee da-yong-oo

Choir:

A de yee jabiok a nyin, jabiok a taam ya de za?

Translation:

Precentor:

I am there to solve (bless) their problems, but they say I am spoiling.

The problem of a bad person will be on another day (in future)

A de yee: (signal for the other singers to join in)

Quoir:

The bad person* is going out (leaving)

The bad person is passing or is the bad person staying?

*The bad person is Akanjaglie (meant ironically). Is she describing her own fate? (She was expelled from her husband’s main homestead).

Nr. 15

Place, time and context: see no 13, sung by Akanjaglie

This is a very well-known song, which Akanjaglie here relates to her own problems. Possible interpretation by Yaw: The death (of her beloved husband?) was hard, but people make things worse by accusing her.

Precentor:

Ayen ba chiem ba bolimmu ka n zuk

A ngman jam li dakings jam viro-ooo (2x) [duok, pl. daata, wood, log]

Choir:

Ayen ba chiem ba bolimmu ka n zuk

A ngman jam li dakings jam viro-ooo

Teng sobri n kan goa yaa yiila yoo.

They (people who hate her) set (chiem) their fire on my head

And come again with big logs (as firewood)

(They) bring them and add (viro) them.

In the night I cannot sleep and I am worrying.

Nr. 16

Place, time and context: sung by Aakanjaglie, see no 13

The following song is common knowledge, but Akanjaglie has used Yari gambieka (her husband’s nickname or praise name) at her own request.

Precentor:

Naamu bu suini nyin la.

Bu jo ni wan dok te ni nya- aaa?

A gen ba ko mi sanbuini mi Yari gambieka*.

Naamu… nya-aaa?

Translation

The heart of the cow (= calf) fell out (got lost)

Whose room did it enter that you (pl.) see (it)?

They killed my dawa-dawa flower, my giant Yarisa-man**.

*gambiek cf. ganduok ‘Riese’.

**Nickname of her husband Akanpaabadai. The Yarisa (Kantussi) are considered tall people. Her husband was of exceptional height.

No 17 (Song of mourning)

Place, time and context: Prof. Rüdiger Schott recorded this song on 28.9.1966 in Sandema-Kobdem. According to Godfrey Achaw, it is not a song of a funeral celebration, but a song of mourning.

N boro a nyeem ya, n boro a nyeem kama.

Ate mi nyeem nyeem bam pai ale kum kali le ba jam ko n mawa.

Jam ko n ma alege mi dek nyiini at me kala namoa.

Jam ko mawa ja ko kowa alege midek nyiini ate mi kala namoa.

Ate me yueni ba daa siak, ba te mu kui nganaase le mu ta cheng yeringa ga yaali baano.

Te mi chang gai yaa baano,

Mi wom wanye ka kum nyiini.

Te mi jam yeni ate bu sang jam, a jam ko n mawa, a jam k n kowa alege mi dek nyiini ate n kala namoa.

Translation:

I have been travelling/roaming about (2x)

I roamed*, roamed, came and met death sitting and they (it) came and killed my mother, they came and killed my mother, leaving me alone and I am sitting suffering.

Came and killed my mother, came and killed my father, leaving me alone and I am sitting suffering.

I said, if they agree they should give me four hoes** to send to the houses and consult a soothsayer.

I heard something, only death came to the houses and they came after me

and killed my mother, came and killed my father and left me alone, and I sat suffering.

*He has to move around because his parents are dead.

**Four hoes (hoe blades) are an exceptionally high payment for a diviner, but he wants to know the cause of death.

18 Death song

Place, time and context: Information by Margaret Lariba; in Fumbisi, when an old man dies, they sing the following song:

Goi naamu a nyin ngmang ngmang (The bushcow disappeared cooly)

Ajaa zaan pungku tenga (came and stood near a rock)

Goi naamu a nyin ngmang ngmang

Bu loansi moai ale peeli (it has red and white patches)

Funeral songs (kum yiila) adopted from U.Blanc (2000: 45ff, 117-232)

Songs for dancing (community songs, not only for funerals)

P. 45f: Wan ale a de

P. 47: Naawen ta wari jam-oa!

P. 47: Ka wan lie, ate wa boari nya?

KUMSA

Kalika dai

Men:

P. 121ff.: Ganduok-ee! (Sandema-Tankunsa)

P. 126ff.: N zuk a wari du!

P. 128ff.: Gbengli duok!

P. 132ff.: Yagaba gong (with sheet music)

Women:

P. 141ff.: Ti miena nong

P. 144ff.: Mi nyini gbong zuk a sing

Tika dai

Entertainment music:

P. 152ff.: Wiena miena bo dila!

Men:

P. 160: Ku dan ko nueri, ku ne yaali jigi!

P. 179ff.: Yeri waang ya! (for deceased men or women)

P. 187f: Waa-wobluk a nyin! (final song for a deceases man)

P. 189: Wen pa nalim te (sung while mats are carried from the cattle yard to the front of the compound)

Women:

P. 167f: Kumu a ko ka liklik (for deceased men)

P. 169f: Ti yeri-nipok ale yiti (for deceased women)

War song accompanying a war dance:

P. 191: Ti boan chaab

Kpaata dai (kpaata yiila)

P. 204f: Fi nye ka nala, jam dela-ya?

Gbanta dai

no example

JUKA

Sinlengsa dance

P. 231: Wa jinla nyini, yaa!

6. FUNERALS ATTENDED BY THE AUTHOR OR HIS ASSISTANTS

1) Kumsa funeral celebrations attended by the author

Atekoba Yeri, Sandema-Choabisa (fn 60-65), 17-18 April 1973: funeral celebration for a blacksmith who died at an advanced age (90) in March 1973. He is said to have fought against Babatu. Only the tika dai was attended.

Asebkame Yeri, Wiaga-Chiok (fn 88.119a – 121a): Kumsa held for a man, a married woman and two children. Only gbanta-dai (6.12.88) was attended.

Adaaminyini’s relatives (compound name?), Wiaga-Sichaasa (fn88,185): Funeral of an old man and an old woman; a short visit was paid on 19.1.89 (tika-dai).

Akadem Yeri (fn88,197+200a+b): Wiaga-Yisobsa: for nearly a dozen men and women, visited on 28.1.1989 (tika) and 31.1.1989 (gbanta).

Acha Yeri, Sandema-Chariba (fn 88,221b+222a); visited on 5.3.89: gbanta for a married woman.

Awuliimba Yeri, Sandema-Kalijiisa-Anuryeri (fn 88,223-226): father of James Agalic, the assistant and informant of R. Schott and F. Kröger; visit: 1st-4th day (7.3.-10.3.89).

Abanarimi Yeri, Wiaga-Chiok-Ayaribisa (fn 233a+b): Kumsa for two married women (rites behind the compound), a returned daughter (in front of the compound) and a boy; visit on gbanta dai (16.3.89)

Agbain Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa (fn 01,3a+b): Visit: tika dai (13.2.01) and gbanta dai (gbanta on two days: 15. and 16.2.01).

Agaab Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa-Chantiinsa (fn 08.15) for two male and five female deceased; visits: 17.2.08: kalika; 21.2.08: gbanta

Adiita Yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa-Guuta; 22.2.08: kalika; 24.2.08: gbanta (tika dropped out, because there was not male person among the deceased).

Ataamkali Yeri, Wiaga-Longsa; compound of the kambonnaab and earth priest Afelik: 25-29.1.2011 (tika dai, kpaata dai, gbanta dai).

2) Kumsa funerals attended by the author’s assistants

Abapik Yeri, Wiaga-Badomsa: 5.9.90 (fn 88,305b) detailed information and photos by Danlardy Leander.

Anyenangdu Yeri, Wiaga-Badomsa, funeral celebration for Anyenangdu, the father of my main informant Anamogsi: 3.3.91-6.3.91 (photos and information by participants M. Striewisch and Danlardy Leander, detailed information and explanations by Anamogsi and other house residents)

Although I myself was not able to attend this funerary celebration at Anyenangdu Yeri, my residence between 1978 and 2011, I received the richest material available fora Kumsa. Even up to 2011, all contentious issues could be discussed and answered.

Atinang Yeri, Wiaga-Badomssa (fn 06, 6a+b; 10a, 27.1.2006): Kumsa mid-March 2005 (not attended, main information provided by Anamogsi, Danlardy and Yaw; held for deceased from Atinang Yeri: Atinang, Angmarisi (younger brother of Atinang), Kweku (young), from Anyenangdu Yeri: Awenbiisi, Asuebisa’s son Akansang, Agoalie, Adiki (Azuma’s young daughter); description in fn only 1. -3. day; imitator of Atinang: Atakabalie (Anyik’s wife), for Angmarisi name omitted, for Agoalie: Ajadoklie. Addition by a letter of Danlardy: when Agoalie died in her parents’ house, she was buried there and a funeral was celebrated. Later, a second funeral service was held at Anyenangdu Yeri.

3) Juka funeral celebrations attended by the author

Ajusong or Ajuyong Yeri, Wiaga-Mutuensa: 24.-27.4.1989, attendance F.K.: 24.4. (cheesika/bogsika, fn 88,270), 27.4. (lokta juka dai, fn 88.270+272), Juka for a deceased diviner.

Ateng Yeri, Na-yeri, Wiaga-Yisobsa, Juka for the late Wiaga chief Asiuk, 6.7. – 12.7. 1994; attendance: 9.7. (sira manika dai, fn 94,14+15a). On 10.7. (lokta juka dai) my assistant Danlardy Leander photographed rites and collected information on my behalf.

4) Juka funerals attended by the author’s assistants

Wiaga-Chiok, May 1990 (fn 88,305b): senlengsa dai: My assistants Danlardy and Adama took photos and collected information.

7. PARTICIPANTS IN ANYENANGDU’S KUMSA FUNERAL

(in preparation)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abasi, Augustine Kututera

1993 Death is Pregnant with Life. Funeral Practices Among the Kasena of Northeast Ghana. Leuven.

1995 Lua-Lia, the “Fresh Funeral”: Founding a House for the Deceased among the Kasena of North-east Ghana. Africa 65,3, 448-475.

Adu, S.V.

1969 Soils of the Navrongo-Bawku Area, Upper Region, Ghana. Memoir no. 5, Soil Research Institute, Kumasi.

Aduedem, Joseph

2018 The Builsa Ghost. A Real Creature or a Mythical Creature? A dissertation submitted to the Department of Philosophy in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of a certificate in philosophy. Moderator: Rev. Fr. Dr. Mathhias Mornah. St. Victor’s Major Seminary (St. Augustine Millenium Major Seminary), Tamale (unpublished)

2019 Builsa Funeral and Final Funeral Rites. Are Builsa Christians (Catholics) Supposed to Perform? Christ the King Catholic Church, Sandema (unpublished manuscript).

2020 Kuub Juka or Ngomsika, the Second Funeral Ceebration. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society. No 13: 54-61 (extract from Aduedem 2019).

2020 The Art of Shepherding: The Origins of Conflict with Farmers in the Cultural Context of the Bulsa. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society. 13, 49-53.

2023 Yog Wiik: Traditional mode of information dissemination. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society. No 14; 80-82.

Agyeman, Dominic Kofi

1973 Erziehung und Nationwerdung in Ghana, dissertation, München.

Allwohl, Adolf

1956 Die Interpretation der religiösen Symbole, erläutert an der Beschneidung. Zeitschrift für Religions- und Geistesgeschichte, 8, 32-40.

Andree, Richard

1978 Ethnographische Parallelen und Vergleiche. Stuttgart.

(Anonyomus)

1973 Builsa Traditional Marriage. Builsa Herald, 2 (Wiaga), 3-4.

(Anonymus)

1984 Marriage in Builsa. Builsa Herald, 3 (Wiaga), 8-10.

Armitage, C.H.

1913 Notes on the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast. United Empire, 4, N.S., 634-39.

1924 The Tribal Markings and Marks of Adornment of the Natives of the Northern Territory of the Gold Coast. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Occasional Papers. London.

Arnheim, Margaret Lariba (née Bawa)

1979 Daam dika – The Brewing of Millet Beer [unpublished manuscript].

Asekabta, Robert (ed.)

1973ff Builsa Herald. Catholic Mission Printing Press, Wiaga.

Atuick, Akangyelewon Evans

2013 Are Final Funeral Rites in Buluk Expensive? Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society. No 7: 36-42.

2015 Tradition and Change in the Bulsa Marriage Process: A Qualitative Study, Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society. No. 8, 92-103.

2020 Women, Agency, and Power Relations in Funeral Rituals: A Study of the Cheri-Deka Ritual among the Bulsa of Northern Ghana. A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology and the University of Wyoming in partial fulfilllment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Anthropology. Laramie, Wyoming August 2020.

Azognab, Francis Aboanchab

2019 Christian Theological Assessment of Death, Funeral Rites and Rituals among the Builsa. A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religious Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for Master of Philosophy in Religious Studies. Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana. College of Humanities and Social Sciences. Department of Religious Studies [unpublished].

2020 Should Christians Attend Traditional Funeral Celebrations? Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society. No 12. [Abridged and revised extracts from his thesis 2019]

Azundem, Stephen

2020 Exploring the Jewish Concept of Ritual Cleansing from a Bulsa Perspective. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society. 13, 41-48.

Barry, Herbert, Child, Irvin L. and Bacon, Margaret

1959 Relation of Child Training to Subsistance Economy. American Anthropologist, 61, 51-63.

Baumann, Hermann

1934 Die afrikanischen Kulturkreise. Africa, 7, 129-139.

1941 Schöpfung und Urzeit. 2nd edition, Berlin.

1955 Die Sonne in Mythus und Religion der Afrikaner. Afrikanistische Studien, ed. J. Lukas. Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, Institut für Orientforschung, Veröffentlichung Nr. 26, Berlin, 252-294. {376}

1959 Kurze Übersicht über den Stand der Kenntnis afrikanischer Völker südlich der Sahara. Bulletin of the International Committee on Urgent Anthropological and Ethnological Research, 2, 101-102.

Baumann, H., Thurnwald, R. and Westermann, D.

1940 Völkerkunde von Afrika. Essen.

Béart, Ch.

1955 Jeux et jouets de l’ouest africain. 2 vols., Mémoires de l’institut Français d’Afrique noire, No. 42, IFAN – Dakar.

Bendor-Samuel, John T.

1965 The Grusi Sub-Group of the Gur Languages. Journal of West African Languages, 2, 47-55.

Bening, R.B.

1971 The Development of Education in Northern Ghana 1908-1957. Ghana Social Science Journal 1,2, 21-42.

Benneh, G.

1970 The Attitudes of the Kusasi Farmer of the Upper Region of Ghana to his Physical Environment. Inst. of Afr. Studies Research Review, 6,3, 87-100.

Bettelheim, Bruno

1975 (German edition) Die symbolischen Wunden. Pubertätsriten und der Neid des Mannes. München: Kindler.

Binger, C.

1892 Du Niger au Golfe de Guinée par le pays de Kong et le Mossi. 2 vols., Paris.

Blanc, Ulrike

1993 Lieder in Erzählungen der Bulsa (Nordghana). Eine musikethnologische Untersuchung. Forschungen zu Sprachen und Kulturen Afrikas, vol. 3., ed. R. Schott. Münster.

2000 Musik und Tod bei den Bulsa (Nordghana). Münster, Hamburg, London: Lit-Verlag.

Brown, Judith K.

1963 A Cross-Cultural Study of Female Initiation Rites. American Anthropologist, 65, 837 – 853.

Bryk, Felix

1968 Neger-Eros. Ethnologische Studien über das Sexualleben bei Negern. Berlin and Köln.

1931 Die Beschneidung bei Mann und Weib. Neubrandenburg.

Builsa Herald, ed. Robert A. Asekabta

1973ff Catholic Mission Printing Press, Wiaga.

Cardinall, A.W.

1920 The Natives of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast. London.

1924 Division of the Year among the Talansi of the Gold Coast. Man, 24, 61-63 {377}.

1931 Tales Told in Togoland. London.

Cerulli, Ernesta and Meyer Fortes

1980 Gli informatori – Informants. L’Uomo, vol. IV, n. 2, (p. 364-365)

Champagné, E.

1928 La religion des noires du Nord de la Gold Coast. Anthropos, 23, 851-860.

Chelala, César

1998 An Alternative Way to stop Female Genital Mutilation. The Lancet, 352, 126.

Christensen, James Boyd

1954 Double Descent among the Fanti. New Haven.

Cohen, Yehudi A.

1964 The Transition from Childhood to Adolescence. Cross-Cultural Studies of Initiation Ceremonies, Legal Systems, and Incest Taboos. Chicago.

The Constitution of the Republic of Ghana

1992 http://ghanareview.com/review/directory/parlia/Garticles.html

Coser, Lewis A.

1957 Social Conflict and the Theory of Social Change. The British Journal of Sociology, 8, 523-535.

Coulibaly, Nafogo

2015 Senufo Funerals in the Folona, Mali. Edited, translated, and photo captions by Barbara E. Frank, African Arts 48,1, 24-41.

Dammann, Ernst

1963 Die Religionen Afrikas. Stuttgart.

Davis, Kinsley

1940 The Sociology of Parent-Youth Conflict. American Sociology Review, 5, 523-535.

de Ganay, S.

1949 On a Form of Cicatrization among the Bambara. Man, 49, 53-55.

de Rachewiltz, Boris

1964 Black Eros. Sexual Customs of Africa from Prehistory to the Present Day. Translated by Peter Whigham, London.

de Waal Malefijt, Annemarie

1968 Religion and Culture. An Introduction to Anthropology of Religion. London, New York.

Delafosse, M

1921 L’année agricole et le calendrier des Soudanais. L’Anthropologie, 31, 105-113.

1923 Terminologie religieuse au Soudan. L’Anthropologie, 33, 371-83.

Deteraka, A.A.

1996 Mortuary Practices among the Kolokuna Ijo of the Niger Delta. West African Journal of Archaeology.

Dickson, K.B.

1971 Nucleation and Dispersion of Rural Settlements in Ghana. Ghana Social Science Journal, 1,1, 116-131.

Dinslage, Sabine

1981 Mädchenbeschneidung in Westafrika. Kulturanthropologische Studien, ed. R. Schott und G. Wiegelmann, vol. 5, Hohenschäftlarn (Bambara, Bulsa, Dogon, Gurma, Malinke und Ubi).

2002 Erotic Folktales of the Bulsa in Northern Ghana. in: M. Hoppál und E. Csonka-Takács (Hgg.), Eros in Folklore, 215-222. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado.

Dittmer, Kunz

1958 Die Methoden des Wahrsagens im Ober-Volta-Gebiet und seine Beziehungen zur Jägerkultur. Baessler Archiv, N.F. 6,1, 1-60.

1958 Ackerbau und Viehzucht bei den Altnigritiern und Fulbe des Obervolta-Gebietes. Paideuma, 6, 429-462.

1959 Ethnographisch bisher nicht oder nur unzureichend untersuchte “Stämme” in Westafrika. Bulletin of the International Committee on Urgent Anthropological and Ethnological Research, 2, 110-111.

1961 Die sakralen Häuptlinge der Gurunsi im Obervolta-Gebiet Westafrika. Mitteilungen aus dem Museum für Völkerkunde in Hamburg, 27. Hamburg {378}.

Drucker-Brown, Susan

1999 The Grandchildren’s Play at the Mamprusi King’s Funeral: Ritual Rebellion Revisited in Northern Ghana. J. Royal Anthrop. Inst. (N.S.) 5, 181-192.

Ehrenreich, Paul

1906 Götter und Heilbringer. Eine ethnologische Kritik. Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 38, 536-610.

Eisenstadt, S.N.

1956 From Generation to Generation. Age Groups and Social Structure. Glencoe, Ill.

Ekundayo, S.A.

1977 Restrictions on personal name sentences in the Yoruba noun phrase. In: Anthropological Linguistics, 19,2: 55-77.

Eliade, Mircea

1967 Das Heilige und das Profane. Vom Wesen des Religiösen. Hamburg.

Evans-Pritchard, E.E.

1963 The Comparative Method in Social Anthropology. London.

Fisch, R.

1911 Nord-Togo und seine westliche Nachbarschaft. Basel.

1912/13 Die Dagbamba. Baessler Archiv, 3, 132-164.

Fokken, H.

1917 Gottesanschauungen und religiöse Überlieferung der Masai. Archiv für Anthropologie, 15, 237-252.

Ford, Clellan Stearns

1964 A Comparative Study of Human Reproduction. Yale University Publications in Anthropology, No. 32, 1964.

Fortes, Meyer

1936 Ritual Festivals and Social Cohesion in the Hinterland of the Gold Coast. American Anthropologist, 38, 590-604.

1938 Social and Psychological Aspects of Education in ‘Taleland’. Supplement to Africa, 11,4.

1940 Divination among the Tallensi of the Gold Coast. Man, 40,9, 12.

1945 The Dynamics of Clanship among the Tallensi. Oxford University Press, London, New York, Toronto.

1949 19673 The Web of Kinship among the Tallensi. Oxford University Press, London.

1950 Oedipus and Job in West African Religion. Cambridge.

1961 Pietas in Ancestor Worship. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 91,2, 166-191.

1955 Names among the Tallensi of the Gold Coast. Afrikanistische Studien, 26 Berlin, 337-349.

Fortes, Meyer, ed.

1962 Marriage in Tribal Societies. Cambridge Papers in Social Anthropology, No. 3, Cambridge.

Fortes, Meyer: see Cerulli, Ernesta 1980

Foster, Philip

1965 Education and Social Change in Ghana. Chicago, London, Toronto.

Frazer, James G.

1963, 19221: The Golden Bough. A Study in Magic and Religion. Abridged Edition in One Volume. London: Macmillan & Co Ltd.

Freud, Sigmund

1940ff. Gesammelte Werke, Frankfurt a.M.

Frobenius, Leo

1904 Das Zeitalter des Sonnengottes. Berlin.

1913 Unter den unsträflichen Aethiopen. Vol. III of the series: Und Afrika sprach. Berlin.

1922 Erzählungen aus dem Westsudan. vol. VIII of the Atlantis series. Jena.

1929 Monumenta Africana. Der Geist eines Erdteils. Frankfurt.

Funke, E.

1917 Der Gottesname in den Togosprachen, Archiv für Anthropologie, 15, 161-63.

Gabianu, Augusta Sena

1967 Trends in der Wandlung der ghanaischen Familie. (M.A. thesis, typescript) Kpandu.

Ghanaian-German Agricultural Development Project Northern and Upper Regions

1974 Crop Production Guide. Handbook for the Extension Worker. Tamale.

Ghana Metereological Service Department

1966-70 Annual Summary of Observations in Ghana.

GhanaWeb

2022 8 February: Female Genital Mutilation still afflicting Northern Ghana – NGOs lament

https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/health/Female-Genital-Mutilation-still-afflicting-northern-Ghana-NGOs-lament-1463824 (access 8.2.2022).

Gluckman, M.

1937 Mortuary Customs and the Belief in Survival after Death among the SE Bantu. Bantu Studies XI.

1954 Rituals of rebellion in south-east Africa. Manchester. (not yet consulted)

1963 Order and Rebellion in tribal Africa. London. (not yet consulted)

1970 Custom and Conflict in Africa. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Goldammer, K. (ed.)

1962 Wörterbuch der Religionen. Begründet von A. Bertholet und Frh. v. Campenhausen, 2.ed., Stuttgart.

Goode, William J.

1951 Religion among the Primitives. London, New York {381}.

Goody, Esther

1962 Conjugal Separation and Divorce among the Gonja of Northern Ghana. in: M. Fortes (ed.), Marriage in Tribal Societies (Cambridge), 14-54.

Goody, Jack

1966 Cross-Cousin Marriages in Northern Ghana. Man, 1,3, 343-355.

19672 The Social Organisation of the LoWiili. London (First Edition 1956).

1962 Death, Property and the Ancestors. A Study of the Mortuary Customs of the LoDagaa of West Africa. Stanford, California.

1969 ‘Normative’, ‘Recollected’ and ‘Actual’ Marriage Payments among the LoWiili of Northern Ghana. 1951-1966. Africa, 39,1, 54-61.

Goody, Jack and Tambiah, S.J.

1973 Bridewealth and Dowry. Cambridge.

Goody, Jack and Esther

1966 The Fostering of Children in Ghana: a Preliminary Report. Ghana Journal of Sociology, 2,1, 26-33.

Gottschalk, Louis, Kluckhohn, Clyde and Angell, Robert

1945 The Use of Personal Documents in History, Anthropology and Sociology. Social Science Research Council, New York, Bulletin 53.

Grindal, Bruce

1972 Growing up in Two Worlds. Education and Transition among the Sisala of Northern Ghana. New York u.a.

Gross, B.A.

1950 Pour la suppression d’une coutume barbare: l’excision. Notes Africaines, 45, 6-8.

Gufler, Hermann

2000 “Crying the Death.” Rituals of Death among the Yamba (Cameroon). Anthropos, 95,2, 349-361.

Haaf, Ernst

1964 Eine Studie über die religiösen Vorstellungen der Kusase. Evangelisches Missions Magazin, 108, 136-158.

1967 Die Kusase. Eine medizinisch-ethnologische Studie über einen Stamm in Nordghana. Stuttgart.

Hammond, Peter B.

1964 Mossi Joking. Ethnology, 3,3, 259-67.

Hauenstein, Alfred

1978 L’excision en Afrique Occidentale. Ethnologische Zeitschrift 2, 83-101.

Hastings, J. (ed.)

1908-26 Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, 12 vols., London.

Hayes, Rose Oldfield

1975 Female Genital Mutilation, Fertility Control, Women’s Roles and the Patrilineage in Modern Sudan: A Functional Analyisis. American Ethnologist 2 (4): 617-633.

Heiler, Friedrich

1961 Erscheinungsformen und Wesen der Religion. Stuttgart.

Herbert, J. et Guilhem, M.

1967 Notion et culte de Dieu chez les Toussian. Anthropos, 62, 139-164.

Herrmann, Ferdinand

1961 Symbolik in den Religionen der Naturvölker. Stuttgart.

1959 Zur Deutung der Initiation. in: Psychopathologie der Sexualität, ed. H. Giese, vol. 1, Stuttgart, 41-51.

Herskovits, Melville J.

1958 Acculturation. The Study of Culture Contact. Gloucester, Mass.

Hien, Victor Mwinsagh and Hébert, J.

1968/69 Prénoms théophores en pays dagara. Anthropos, 63/64, 566 – 571.

Hilger, M. Inez

1960 Field Guide to the Ethnological Study of Child Life. Human Relation Area Files Press, New Haven.

Hilton, T.E.

1965 Le peuplement Frafra, district du Nord Ghana. Bulletin IFAN, 27, B, 678-700.

1968 The Settlement Pattern of the Tumu District of Northern Ghana. Bulletin IFAN, 30, B, 868-883.

Holas, B.

1951 Aspects modernes de la circoncision rituelle et de l’initiation ouest-africaine. Notes Africaines, 49, 4-11.

1966 Les Sénoufo (y compris les Minianka). Paris.

Holden, J.J.

1965 The Zabarima Conquest of North-West Ghana, Part I, Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. vol. VIII (Legon), 60-86.

Hosken, Fran P.

1977/78 Female Circumcision in Africa. Victimology: An International Journal, 2, 487-498.

Jahoda, Gustav

1958 Boys’ Images of Marriage Partners and Girls’ Self-Images in Ghana. Sociologus, 8, 155-169.

1959 Love, Marriage, and Social Change: Letters to the Advice Column of a West African Newspaper. Africa, 29,2, 177-190.

Jensen, Ad. E.

1933 Beschneidung und Reifezeremonien bei Naturvölkern. Stuttgart.

1960 Mythos und Kult bei Naturvölkern. Religionswissenschaftliche Betrachtungen. Wiesbaden.

Kadri, John

1986 The Practice of Circumcision in the Upper East Region of Ghana (unpublished manuscript).

Kilson, Marion

1968/69 The Ga Naming Rite. Anthropos, 63/64, 904-920.

Klages, Jürg

1953 Navrongo. Ein Afrikabuch mit 108 Aufnahmen. Zürich.

Kluckhohn, Florence R.

1940 The Participant-Observer Technique in Small Communities. American Journal of Sociology, 46, 331-343.

Knudson, Christiana Oware

1994 The Falling Dawadawa Tree. Female Circumcision in Developing Ghana. Højbjereg (Dänemark): Intervention Press.

Köhler, Oswin

1958 Zur Territorialgeschichte des östlichen Nigerbogens. Baessler Archiv, N.F., 6, 229-261.

Konings, Piet

1984 Capitalist Rice Farming and Land Allocation in Northern Ghana, Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law (Littleton, Colorado), 22, 89-119 [based on field-research on the Gbedembilisi rice project].

1986 The state and rural class formation in Ghana: A comparative analysis. London, Boston,Melbourne and Henley.

König, René, ed.

1969 Das Interview. Formen, Technik, Auswertung. Praktische Sozialforschung 1. Köln und Berlin (7the edition).

Krämer, Paul and Ini Damien

1999 Can Female Excision Be Transformed into a Symolical Rite? The Experience of Lobi Women in Burkina Faso. Entwicklungsethnologie 8,1, 12-23.

Krysmanski, Hans Jürgen

1971 Soziologie des Konflikts. Materialien und Modelle. Reinbeck.

Kröger, Franz

1978 Übergangsriten im Wandel. Kindheit, Reife und Heirat bei den Bulsa in Nord-Ghana. Hohenschäftlarn bei Munchen: Kommissionsverlag Klaus Renner.

1980 The Friend of the Family or the Pok Nong Relation of the Bulsa of Northern Ghana. Sociologus 30,2, 153-165.

1982 Ancestor Worship among the Bulsa of Northern Ghana. Kulturanthropologische Studien, ed. R. Schott und G. Wiegelmann, vol. 9, Klaus Renner Verlag, Hohenschäftlarn bei München.

1984 The Notion of the Moon in the Calendar and Religion of the Bulsa (Ghana). Systèmes de Pensée en Afrique Noire, Cahier 7, 149-151.

1986 Der Ritualkalender der Bulsa (Nordghana). Anthropos 81, 4/6, 671-681.

1987 Traditionelle und schulische Erziehung bei den Bulsa in Nordghana. Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 112, 2, 269-283.

1992 Buli-English Dictionary. With an Introduction into Buli Grammar and an Index English-Buli. Münster und Hamburg: Lit Verlag.

1992 Schwarze Kreuze und Wahrsageobjekte: tote und lebende Symbole der Bulsa, in: W. Krawiets, L. Pospišil und S. Steinbrich (eds), Sprache, Symbole und Symbolverwendungen in Ethnologie, Kulturanthropologie, Religion und Recht. Festschrift für Rüdiger Schott zum 65. Geburtstag. Berlin: Duncker und Humblot, 93-107.

1997 Brautraub? – Ein Beispiel aus Nordghana. in: S. Eylert, U. Bertels, C. Lütkes (eds.): Mutterbruder und Kreuzcousine – Einblicke in das Familienleben fremder Kulturen. Münster, New York, München, Berlin, 35-40.

1997 Wie finde ich einen Mann, der mich schwängert? – Das Problem der Unfruchtbarkeit in Nordghana. in: S. Eylert, U. Bertels, C. Lütkes (eds.): Mutterbruder und Kreuzcousine – Einblicke in das Familienleben fremder Kulturen. Münster, New York, München, Berlin, 68-74.

2001 Materielle Kultur und traditionelles Handwerk bei den Bulsa (Nordghana). Forschungen zu Sprachen und Kulturen Afrikas (ed. R. Schott), 2 vols., Lit-Verlag, Münster und Hamburg.

2003 Elders – Ancestors – Sacrifices: Concepts and Meanings among the Bulsa. in: Ghana’s North. Research on Culture, Religion and Politics of Societies in Transition, Peter Lang Verlag, 243-262.

2005 Bulsa Traditional Religion. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society. 4, 39-42.

2005 Christian Churches and Communities in the Bulsa District. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society. 4, 43-57.

2005 A Visit to a Meeting of Akawuruk and her Adherents. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society. 4, 54-56.

2009 Das Kind muss einen Namen haben. Namengebung in Ghana und bei uns. In: L. Raesfeld und R. Bertels (eds.): Götter, Gaben und Geselligkeit. Einblicke in Rituale und Zeremonien weltweit. Münster, New York, München und Berlin: Waxmann Verlag.

2012 Die dauerhafte Etablierung von rituellen Abweichungen. Das lakori-Prinzip bei den Bulsa Nordghanas. Anthropos 107, 1-12.

2013 Das Böse im göttlichen Wesen. Der Mungokult der Bulsa und Koma (Nordghana). Anthropos 108,2, 495-513.

2016 Returning Home as a Dead Man – The Bulsa ngarika-burial. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society. No. 9, 53-61.

2016 Miniatures in Bulsa Religion and Magic. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society. No. 9, 62-68.

2017 The Earth Cult of the Bulsa (Northern Ghana). Special Issue of Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society.

2017 Religious and Rebellious Elements in Bulsa Funeral Rituals. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society 10, 97-113.

2018 Bulsa Cultural Heritage and the Possibilities of Tourism. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society 11, 41-57.

2019 The Medical System of the Bulsa. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society. 12 (2019), 58-88. (https://buluk.de/new)

2020 The Koma and Bulsa of Northern Ghana. Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society. 13, 62-70.