Franz Kröger

Rites of Passage in Transition

Childhood, Maturity, Marriage and Death among the Bulsa in Northern Ghana

Second revised and extended edition 2023

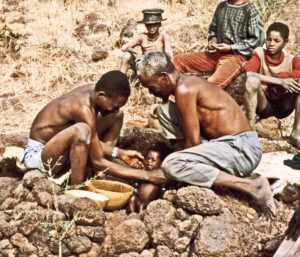

A child is dedicated to an Earth Shrine

The first edition (1978): Title

Cover photo:

Note on the cover photo:

The picture shows L. Amoak (with cap), one of the main informants of this work [from 1978], with his nephew Ayomo Atiim, who is about ten years old and who performs the function of a sacrificer in L. Amoak’s house, and a neighbour. A sacrifice is made to the ancestress’s compound, and where her shrine is going to be rebuilt. L. Amoak has pressed the earth taken from this spot into a round, knobbed pot (in the left foreground of the picture). This vessel with earth (ma-bage) represents the ancestress to whom L. Amoak from now on will make annual offerings.

D6

© Copyright Franz Kröger 1978

All rights reserved

Printed in Germany

ISBN 3-87673-058-2

Franz Kröger: Übergangsriten im Wandel

Cultural Anthropological Studies

Edited by Rüdiger Schott and Günter Wiegelmann

1978

KOMMISSIONSVERLAG KLAUS RENNER

Hohenschäftlarn bei München

PREFACE [1978]

The material for this dissertation was obtained during my two-year stay in Ghana (December 1972–December 1974). I spent most of my time in Cape Coast, where I worked as a lecturer in German on behalf of the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service). The fieldwork among the Bulsa in Northern Ghana was conducted during my trimester breaks (12–22 April 1973; 19 June–5 September 1973; 21 December 1973–10 January 1974; 5–15 April 1974; 19 June–7 September 1974). In addition, I was able to gather much information from the Bulsa residing in Cape Coast during the lecture period, enabling me to revise the research material from Northern Ghana with them.

Initially, I intended to collect material from the Bulsa on generational conflicts, especially those caused by modern attitudes of the youth, including topics like school attendance or the adoption of Christianity. However, it soon became apparent that due to school attendance in boarding or all-day schools and the early emigration of school leavers to the towns of southern Ghana, conflicts between parents and their school-educated children could not fully develop.

In the traditional field, it turned out that often different attitudes towards so-called ‘life crises’ and their rites of passage (e.g. one’s choice of marriage partner, advocacy for or rejection of excision, performance of traditional rites, sacrifice) create conflicts between parents and their children. An intensive study of rites of passage became necessary, resulting in the focus of the work shifting from the conflicts to the rites themselves and their functions in a changing society.

I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to the DAAD, which created the financial conditions for the field research work, to Prof. R. Schott for his numerous pieces of advice, suggestions and information and, last but not least, to the many Bulsa informants – old and young, educated and illiterate.

PREFACE TO THE INTERNET EDITION (2023)

More than forty years have passed since the first edition of The Bulsa Rites of Passage (1978) was printed. The fieldwork for this first edition was conducted five years beforehand (1972–74). In the following period (1978–2022), I have attempted to verify or falsify my data on the rites of passage and, above all, to collect new supplementary material in addition to other major research (see below).

The focus of my work has shifted in local terms from Sandema-Kalijiisa-Yongsa to Wiaga-Sinyansa-Badomsa since the late 1970s. In the beginning, the gates to the Badomsa compound, Adeween Yeri or Asik Yeri, had been opened to me by my long-time friend, Mr. Leander Amoak, the head (yeri-nono) of this compound (yeri) and a large lineage segment. After Leander’s death, Anamogsi of Anyenangdu Yeri (Wiaga-Badomsa) had become a more than sufficient replacement. During my 15 stays (1972–74, 1978, 1981, 1984, 1986, 1988–89, 1991, 1994, 1997, 2001–02, 2002–03, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2011) in Bulsa and my stay in Accra (2012) for archive work, I always maintained contact with Anyenangdu Yeri. I was thus able to research and observe all kinds of activities unrestricted. After 1984, I occupied my own courtyard (dabiak) in this compound, and a wife of the compound head, Anamogsi, prepared hot traditional meals for me. Although the focus of my work after 1974 shifted to other topics (e.g. the earth cult, divination, material culture, language studies for a dictionary), during my time as a resident of the compound, I was involved in everyday life while being permitted to observe the ritual life of Anyenangdu Yeri and its more-or-less related neighbouring compounds (Atinang Yeri, Atuiri Yeri, Angoong Yeri, Abasitemi Yeri, and Akanming Yeri).

While working on the data collected there for a new edition of Rites of Passage, a problem arose in how to link the new results with those of the first edition. This prompted my decision (my remaining time and health also did not allow any other way) to forego writing an entirely new book, which would involve merging the data of each field visit into a homogeneous work, instead supplementing my 1978 dissertation with new data and findings. Later surveys have substantively confirmed the results of my initial field research, further justifying this choice.

When I was seeking a topic for my dissertation and was making plans for a basic structure (after 1973), a problem arose. Initially, several key rites of passage – birth, maturity, marriage and death – were intended as the work’s focal points. Although I was able to collect extensive material on the latter sub-theme at that time, crucial data were still missing; thus, a complete understanding of the function and meaning of all rites in their chronological sequence was unfeasible. Furthermore, by including a chapter on death, the extensive presentation and analysis of the existing material would have gone beyond the scope of a dissertation.

With the agreement of my doctoral supervisor, Prof. R. Schott, I thus chose to omit the rites of passage associated with the death of a human being in this work, reserving them for a later monograph in the form of Goody’s Death, Property and the Ancestors (1962). When that plan also failed because of a preoccupation with other topics and publishing works on them, all that remained was to make an insertion in the second (Internet) edition of The Bulsa Rites of Passage. However, a fully formulated chapter was no longer possible here due to my age (86) and health. The sub-chapters on the celebrations of the dead may thus seem more like an articulated collection of material than a thorough investigation. However, this shortcoming could be somewhat compensated for by some essays at the end of this study.

Crafting the second edition of this work unearthed new questions. How far should the identities of the acting persons and my informants be withheld for reasons of data protection? Should their names be omitted, shortened or replaced by a pseudonym? When writing the first edition of the text (before 1978), I perhaps approached this problem with insufficient concern. The description and analysis of my field research data were primarily intended to meet the demands of an examination thesis, not necessarily for broader publication. I did not know or anticipate whether my dissertation would be published or if any Bulsa would ever come into possession of this German-language text and then study it more closely. Today, however, the situation differs substantially. Bulsa men and women have studied in Germany, are deeply interested in the traditional culture of their ethnic group, and can readily translate a digitized German text into English with a translation program (e.g. from Deeple or Google Translate) available on the Internet. Therefore, in the new edition, I have shortened or modified many names or chosen alternate names from the many names of the Bulsa persons concerned that are less known in their social environment. I have also omitted photos of recognizable people participating in rites of female excision or adultery (kabong). Other names and described actions remained unchanged if I received explicit permission or consent to publish them. For example, Anamogsi, the head of Anyenangdu Yeri (my research’s local focus), explicitly permitted me to publish unchanged names and events from his compound and the neighbouring compounds under his supervision as their kpagi (elder).

Regarding the first edition’s content, I seek to correct two previous statements in this preface. In the description of the rites of female ancestor veneration, my account (Chapter V, 3b) about the fetching of the ma-bage shrine implied a connection between the veneration of female ancestors and the earth cult. When the earth, as the contents of the ma-bage pot, was fetched from the hill of the earth shrine (tanggbain), Pung Muning, it was not because the place belonged to the shrine but because the ancestress’s compound had once stood there. In addition, in stating that the tanggbain of Kanjaga has any connection with the juik (mungo) cult or that juik is even its proper name, I have unfortunately adopted information to this effect without verification.

Correcting formal elements, such as those of the Buli spelling, remains more problematic. This was the case during my initial field research (1972–74), and even today, there are often several spellings for a single term in circulation. In the new edition, I have often retained the old spelling when it is still practised today (among others). However, I have preferably used words of a different spelling if presented in the Buli English Dictionary and have adopted terms that have become officially accepted in a different spelling or where my spelling was incorrect in the first edition (e.g. Siniensi for Sinyensi). The use of the present tense for some areas, including many social and political phenomena and activities, is also no longer suitable for the 2023 Internet edition of this work since it is precisely in these areas where sizeable changes have occurred in recent years.

Finally, the author is aware that the large amount of recent data used occasionally creates a patchwork of text and, thus, a sometimes uneven reading experience as an overall text. However, as the author, I did not seek to create a creative, stylistic work of art but primarily to make my numerous data and findings available in a practical form to subsequent researchers of the Bulsa culture.

Page numbers of the original 1978 edition have been placed in curly brackets {…} in the Internet edition.

CONTENTS

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION (1978)

PREFACE TO THE INTERNET EDITION (2023)

INTRODUCTION

1. THE COUNTRY

a) Geographical location and neighbouring ethnic groups

b) Climate and the agricultural and ritual annual circle

c) Soil characteristics and landscape

d) Settlements

2. THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL STRUCTURE

3. ETHNOGRAPHIC LITERATURE

a) Bulsa

b) Neighbouring ethnic groups

4. DISCUSSION OF THE TOPIC

5. METHOD AND WORKING TECHNIQUE

6. MODE OF PRESENTATION

ENDNOTES INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I: PREGNANCY

1. PROCREATION AND INFERTILITY

2. PREGNANCY OF UNMARRIED WOMEN

3. RECOGNITION AND PROCLAMATION OF THE FIRST PREGNANCY

4. TABOOS, BANS AND RULES OF CONDUCT

a) Food bans

b) Prohibitions on seeing certain things and persons

c) Rules of conduct for the pregnant woman

d) Provisions for the spouse

5 . PREGNANCY RITUALS AFTER FREQUENT MISCARRIAGES

ENDNOTES CHAPTER 1: PREGNANCY

CHAPTER II: BIRTH

1. BIRTH PROCESS

2. STRINGS AND AMULETS

a) Strings and fibres

b) Amulets

3. MOTHER AND CHILD AFTER BIRTH

a) Food for the mother

b) The mother’s behaviour and condition

c) Breastfeeding

d) The child’s bath

e) Restrictions and requirements for the child

4. RITES AFTER BIRTH

a) Robert Asekabta’s pobsika

b) Ayabalie’s pobsika and applying black crosses

Excursus: Blowing ashes in other situations

c) Outdooring a child

5. UNUSUAL PHENOMINA AT BIRTH

a) Twins

b) Malformations and physical peculiarities

c) Other harmless phenomena

d) Children born on the same day

e) Children born at new moon

6. DEATH AND BURIAL OF YOUNG CHILDREN

7. REBIRTH

8. ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIOUR AMONG THE STUDENT GENERATION

ENDNOTES CHAPTER 2: BIRTH

CHAPTER III : THE GUARDIAN SPIRIT, NAMING AND NAMES

A) THE GUARDIAN SPIRIT AND NAMING

1. THE ANCESTRAL SEGRIKA

a) An ancestral segrika in Wiaga Badomsa (Asik Yeri, 1973)

b) An ancestral segrika in Sandema Kalijiisa (Achaw Yeri, 1974)

c) An ancestral segrika in Wiaga Badomsa (Anyenangdu Yeri, 1988)

d) An ancestral segrika in Wiaga Guuta (Ataasa Yeri, 1990)

2. THE TANGGBAIN SEGRIKA

a) Report on a tanggbain segrika in Wiaga Zuedema (before 1972)

b) A tanggbain segrika in Wiaga Badomsa (Anyenangdu Yeri, 1988)

c) Another tanggbain segrika in Wiaga Badomsa (Ayoling Yeri, 1989)

d) Another tanggbain segrika in Wiaga Badomsa (Anyenangdu Yeri, 2005)

e) Secondary shrines

3. THE JUIK SEGRIKA

4. THE TONGNAAB SEGRIKA IN WIAGA YISOBSA NAPULINSA

5. THE TIIM SEGRIKA

6. THE JADOK SEGRIKA

7. THE KAYAK SEGRIKA

8. THE NANGMWURK (NANGMARUK?) SEGRIKA

9. FURTHER INFORMATION ON SEGRIKA RITUALS

a) The occasion

b) The child’s age

c) The name givers

d) The guardian spirit (segi)

B) NAMES

1. PRELIMINARY METHODOLOGICAL REMARKS

2. FORMAL AND STRUCTURAL CONSIDERATIONS OF BULI NAMES

a) Prefixes and suffixes

b) Translation aids

c) Syntactic structure of the names

3. POSSIBILITIES FOR STRUCTURING AND CLASSIFYING BULI NAMES

a) Concretes

b) Place names

c) Events at the time of birth

d) Complaints of the father

e) Conflicts

f) Wisdom and behavioural advice

g) Theophore names

h) Adoptive names

i) Slave names

k) English names in Buli form

4. OUTLOOK FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

5. FOREIGN NAMES

a) Haussa and Islamic names (sagi yue)

b) Akan names (sagi yue)

c) Christian and English names

6. NAME BEARERS AND NAMES

ENDNOTES CHAPTER 3: THE GUARDIAN SPIRIT, NAMING AND NAMES

CHAPTER IV: SCARIFICATIONS

1. SCARIFICATION AND RITES OF PASSAGE

2 . TRIBAL MARKS (nyaga)

a) Forms and their local distribution

b) Execution of cutting scars

3. SCAR ORNAMENTATION FOR AESTHETIC OR PLAYFUL MOTIFS

4. UMBILICAL CIRCUMCISION (SIUK-MOBKA)

5. SCARIFICATIONS AFTER MISCARRIAGES

6. AKAN SCARS

7. EXCURSUS: TATTOOING

8. EXCURSUS: BODY PAINTING

9. STUDENTS’ ATTITUDES TOWARDS SCARIFICATION AND TATTOOING

ENDNOTES CHAPTER 4: SCARIFICATIONS

CHAPTER V: WEN RITES

1. NYING, CHIlK, WEN, PAGREM

2. WEN-PIIRIKA

a) A wen-piirika celebration in Asik Yeri (1973)

b) Additions by other informants (before 1978)

c) Supplements after 1974

1. Asik Yeri (Badomsa, 1981)

2. Anyenangdu Yeri (Badomsa, 1988)

3. Awenlami Yeri (Longsa, 1988)

4. Ateebnaab Yeri (Mutuensa 1988)

5. Akanjoliba Yeri (Mutuensa 1989)

6. Abasitemi Yeri (Badomsa 1989)

7. Angaung Yeri (Kubelinsa 1989)

8. Atinang Yeri (Badomsa 2001)

9. Anyenangdu Yeri (Badomsa 2003)

10. Anyenangdu Yeri (Badomsa 2008)

d) Locations of the wen-bogluta

e) Sacrifices and accessories of the shrines

1. Liquids and food

2. Sacrificial animals

3. Accessories

f) The wen after the holder’s death

g) Wen-bogluta of the Bulsa in Southern Ghana

h) Function and meaning of the wen-piirika rites and the personal wen

3. WEN RITES OF FEMALE PERSONS

a) Female wen-bogluta

b) Transformation and adornment of a female wen-bogluk

c) Construction of a female wen-bogluk (ma-wen) in front of the compound

d) Rituals of ma-bage transfers

4. WEN SHRINES IN THE COMPOUNDS

ADEWEEN YERI (WIAGA-BADOMSA)

a) Genealogical overview and site plans

b) Site-plan of Adeween Yeri

c) Names of the genealogical overview and the site plan

AMOANUNG YERI

a) Genealogy

b) Names of the genealogical overview and the site plan

c) Site plan of Amoanung Yeri

ANYENANGDU YERI

a) Census of Anyenangdu Yeri, 1997

Anamogsi’s ancestors

Anamogsi’s family

b) Compound plan of Anyenangdu Yeri, 1994 (with shrines)

c) Names of the shrines in Anyenangdu Yeri

d) Graves in Anyenangdu Yeri

5. SOCIO-ECONOMIC SIGNIFICANCE OF OWNING ANCESTRAL SHRINES

6. CONFLICTS OF CHRISTIAN STUDENTS WITH THEIR FATHERS

7. WEN VENERATION AND SUN CULT

8. CONSIDERATIONS ON THE SHAPES OF BOGLUTA

ENDNOTES CHAPTER 5: WEN RITES

CHAPTER VI: EXCISION AND CIRCUMCISION

1. INTRODUCTION TO CHAPTER VI

1.1 Questions concerning terminology

1.2 Methodological difficulties in the collection of material

2. EXCISION IN BULSALAND

3. EXECUTION OF FEMALE EXCISION

4. THE GIRL IN HER PARENTS’ OR HER PARENTS-IN-LAWS’ COMPOUND

4.1 Pobsika and food taboos

4.2 Treatment of the wound

4.3 Gaasika and ponika

4.4 Rituals of passage and excisions (2022)

4.4.1 Taboos

4.4.2 Pobsika (ash blowing)

4.4.3 Ponika (head shaving)

4.4.4 Gaasika

5. EXCISION AND BIRTH

6. ATTITUDEs OF EXCISED GIRLS TO EXCISION

6.1 Positive attitude towards excision

6.2 Indifferent attitude

6.3 Rejection of excision

7. EXCISION AND SCHOOL

8. MALE’ CIRCUMCISION

ENDNOTES CHAPTER 6: EXCISION AND CIRCUMCISION

CHAPTER VII: COURTING AND MARRIAGE

1. MARRIAGE BANS

a) Marriage bans for large groups

b) Individual marriage bans

c) Violation of a marriage prohibition: an example

d) Summary

2. COURTSHIP AND MARRIAGE

a) Marriage without courting

b) Getting to know each other and courting (lie yaaka or dueni dek)

c) Home visits

d) Violent abductions

e) Abduction with the consent of the bride and the following marriage rituals

f) Older forms of marriage

g) Marital sexual intercourse

h) Akaayaali

i) Visit of the bride’s brothers

j) Visit of the bride’s mother

k) The closing of the gate (nansiung ligka)

l) Farmwork of the husband for his parents-in-law (chichambiri)

m) Costs of a marriage

3. POLYGYNOUS MARRIAGE

4. ADULTERY

5. DISSOLUTION OF MARRIAGE

6. REMARRIAGE OF THE WIFE AFTER HER HUSBAND’S DEATH

7. MODERN TENDENCIES IN THE YOUNGER GENERATION

a) Observance of marriage bans and prescribed enmities

b) Courtship, marriage, and school

c) Christianity and marriage

c1) Case studies and conflicts

c2) Christianity and Polygyny in E. Hillman’s study ‘Polygamy Reconsidered’ (1975)

c3) Registration of marriages required by the state

c4) Modern marriages, according to Evans A. Atuick (Buluk 8, 2015: 92–103)

ENDNOTES CHAPTER 7: COURTING AND MARRIAGE

CHAPTEER VIII: DEATH, MOURNING AND BURIAL

Descriptions and processed field notes

1. INTRODUCTION: ON RESEARCH INTO RITUALS OF DEATH

2 DEATH (Ku-yogsik or ku-palik, ‘fresh’ or ‘new death’)

2.1 The positive evaluation of earthly life

2.2 Causes of death

2.3 Kum-biok, the evil death

2.3.1 Death during hunting accidents

2.3.2 Death outside the compound

2.3.3 Death during pregnancy

2.3.4 Death of a leper

2.3.5 Dying from a curse

2.3.6 Suicide

2.3.7 The swollen body (nying fuusika) of the deceased as a sign of kum-biok

2.3.8 Lightning

2.4 Occurrence of death

2.4.1 A diviner (baano) should discover the illness’s spiritual origin.

2.4.2 The medicine man (tebroa or tiim-nyono) is consulted for advice

2.4.3 Visit of a clinic or hospital

2.4.4 Healing through charismatic people

2.4.5 Arrangements for the expected death

2.4.6 The dead person is laid on a mat

2.4.7 Determination of death

2.5 Kuub darika, the announcement of death

2.5.1 Reasons for postponement

2.5.2 Performance of the kuub darika

2.6 Notification of the earth priest (teng-nyono)

2.7 Mourning and mourning visits

2.8 Mat gifts at the burial visits and later

2.8.1 Gifts at funeral visits before the death celebrations

2.8.2 Gifts of mats during funeral celebrations

3. BURIALS

3.1 Activities before the burial

3.2 Burial site

3.2.1 Important old men, may be buried in an inhabited courtyard.

3.2.2 Young, childless men and women may be buried in the cattle yard (nangkpieng)

3.2.3 Outside the compound

3.2.4 Infants who do not have younger siblings are buried in or near the trash heap (tampoi).

3.2.5 Children with younger siblings may be buried along the footpath

3.2.6 Kikita are buried in the ‘bush’ (sagi) or in an ant hill.

3.2.7 Deceased pregnant wives are buried away from the compound.

3.2.8 Burial in old graves does not exist among the Bulsa.

3.2.9 Discussion in the Bulsa Facebook group Buluk Kaniak about ‘treating dead bodies’

3.3 The grave diggers and their vayaam medicine

3.3.1 The gravedigger Ansoateng

3.3.1.1 Ansoateng’s vocation and activity

3.3.1.2 Ansoateng’s medicines and activities

3.3.2 Vayaam rituals at Angaung Yeri, Mutuensa

3.3.3 A vayaam ritual in Anduensa Yeri, Wiaga-Chiok

3.3.4 Further information on vayaam medicine

3.4 Burial of adults

3.4.1 Death of a married woman (case study from Wiaga-Yisobsa)

3.4.1.1 Treatment of the dead woman and rituals before burial

3.4.1.2 Suurika

3.4.1.3 Announcement of death (kuub darika) and condolence visits

3.4.1.4 The excavation of the grave and the burial

3.4.1.5 Ta-pili Yika (hanging of the death mat)

3.4.1.6 Discussions in Apok Yeri about the noai-boka and gaasika rituals

3.4.1.7 Further information on the gaasika

3.4.1.8 Nyiinika (purification by smoke)

3.4.1.9 Excursus: Daungta suurika: purification by smoke and water.

Daungta suurika in Aniok Yeri

3.4.2 Apunglie’s Death

3.4.3 Additions by other informants and authors on adult burials

3.4.3.1 Additions by J. Aduedem (Sandema-Bilinsa-Pungsa)

3.4.3.2 Additions by Leander Amoak (Wiaga-Badomsa)

3.4.3.3 Information by Danlardy Leander (1983)

3.4.3.4 Additions by Godfrey Achaw (Sandema-Kalijiisa)

3.4.3.5 Additions by Anamogsi (Badomsa)

3.4.3.6 Additions by Margaret Arnheim (Gbedema)

3.4.3.7 Information by Sebastian Adaanur and own observation

3.4.3.8 Individual observations Franz by Kröger

3.5 Burial of infants

3.5.1 The example of Akanchainfiik in Anyenangdu Yeri, Badomsa

3.5.2 Further information on the deaths and burials of infants

3.5.3 Rebirth of infants

3.6 Death and the burial of a kikiruk

3.7 Ngarika: Burial of a person deceased in a foreign area

3.7.1 Ngarika in Achaab Yeri, Badomsa

3.7.2 Returning Home as a Dead Man – The Bulsa Ngarika Burial (in English)

3.7.2.1 Digging the Grave and Burying the Mud Figure

3.7.2.2 Ta-pili yika (hanging up the mat) and nyiinika (smoking)

3.7.2.3 Comparison with Ordinary Burials

3.7.2.4 Ngarika Burials in Modern Times

3.7.3 Further information on ngarika burials

3.8 The noai-boka ritual

3.8.1 Information from Wiaga

3.8.1.1 Noai-boka after a fatal accident

3.8.1.2 After a conflict

3.8.2 Information from Sandema

3.8.2.1 Description by Godfrey Achaw from Sandema-Kalijiisa

3.8.2.2 Excerpts from Aduedem’s unpublished study (2019)

3.8.3 Information from Gbedema by Margaret Arnheim

ENDNOTES CHAPTER 8: DEATH; BURIAL… 68

CONCLUSION

1. THE ETHNOGRAPHIC DATA IN A BROADER FRAMEWORK

2. COMPARISON WITH OTHER ETHNIC GROUPS IN NORTHERN GHANA

3. FUNCTION OF THE RITES OF PASSAGE

4. TRADITIONAL RITES IN MODERN SOCIETY

ENDNOTES: CONCLUSION

APPENDIX

1. BULI TERMS USED IN THIS STUDY (A SELECTION)

2. ABBREVIATIONS

3. MAIN INFORMANTS AND ASSISTANTS

3.1 Godfrrey Achaw (Sandema-Kalijiisa)

3.2 Robert Asekabta (Sandema-Abilyeri) and other informants from Sandema

3.3 Leander Amoak and Danlardy Amoak (from Wiaga-Sinyansa-Badomsa, Asik/Adeween Yeri)

3.4 Anamogsi Anyenangdu (from Wiaga-Sinyansa-Badomsa, Anyenangdu Yeri)

3.5 Akanming Awasiboa (from Siniensi, resident in Wiaga-Badomsa until 1994)

3.6 Yaw Akumasi Williams (from Wiaga-Yisobsa-Napulinsa, Apok Yeri)

3.7 Margaret Arnheim, née Lariba Bawa (from Gbedema-Gbinaansa, Akanwari Yeri)

3.8 Bulsa Facebook groups (Bulubisa Meina Yeri, Buluk Kaniak, Buluk in Focus and others)

4. GENEALOGIES

4.1 Genealogy Abadomgbana-bisa

4.2 Genealogy Ayarik-bisa

4.3 Genealogy Apok Yeri (Napulinsa)

5. SUPPLEMENTARY SUMMARIES AND ANALYSES OF THE FUNERAL RITUALS

5.1 Funerals and rites of passage

5.1.1 Rites of passage according to A. van Gennep and V. Turner

5.1.2 The three phases in the funeral celebrations of the Bulsa

5.1.2.1 Changing established gender roles

5.1.2.2 Non-observance of taboos (kisita, sing. kisuk)

5.1.2.3 Ritual theft without sancitions (chiaka, snatching)

5.1.2.4 Sexual licence

5.1.2.5 Aggression and open rebellion

5.2 The role of women in funerary rituals

5.3 Redundancies

5.4 Funeral Songs

5.5 List of funerals and mortuary ceremonies attended by the author

5.7 Participants in Anyenangdu’s kumsa funeral ceremony (in preparation)

INDEX OF MAPS, TABLES AND FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT

MAP OF THE BULSA AREA (FIRST EDITION, 1978)

MAP OF THE BULSA AREA (2021)

BULSA AGRICULTURAL ACTIVITIES IN THE ANNUAL CYCLE

CLIMATE VALUES OF THE NAVRONGO STATION

OVERVIEW OF THE SYNTACTIC STRUCTURE OF THE BULI NAMES

PARTICIPANTS IN THE MA-BAGE RITES IN THE HOUSE OF ADEWEEN YERI

1. Genealogical overview

2. Names

WENA IN THE HOUSE OF ADEWEEN YERI: GENEALOGICAL OVERVIEW

BOGLUTA AND OTHER SACRED PLACES AND OBJECTS IN THE HOUSE OF ADEWEEN YERI

1. Names

2. Site plan

WEN-BOGLUTA lN AMOANUNG YERI (SANDEMA-KALIJIISA)

1. Genealogical overview

2. Names

3. Bogluta of living persons in the courtyard of the yeri-nyono (site plan)

DRAWING OF A GIRL IN HER EXCISION COSTUME

MARRIAGE SYSTEM OF WIAGA

A COMPARATIVE OVERVIEW OF SOME RELIGIOUS TERMS

A COMPARISON OF RITUAL SUBSTRUCTURES

PREFACE [1978]

The material for this dissertation was obtained during my two-year stay in Ghana (December 1972–December 1974). I spent most of my time in Cape Coast, where I worked as a lecturer in German on behalf of the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service). The fieldwork among the Bulsa in Northern Ghana was conducted during my trimester breaks (12–22 April 1973; 19 June–5 September 1973; 21 December 1973–10 January 1974; 5–15 April 1974; 19 June–7 September 1974). In addition, I was able to gather much information from the Bulsa residing in Cape Coast during the lecture period, enabling me to revise the research material from Northern Ghana with them.

Initially, I intended to collect material from the Bulsa on generational conflicts, especially those caused by modern attitudes of the youth, including topics like school attendance or the adoption of Christianity. However, it soon became apparent that due to school attendance in boarding or all-day schools and the early emigration of school leavers to the towns of southern Ghana, conflicts between parents and their school-educated children could not fully develop.

In the traditional field, it turned out that often different attitudes towards so-called ‘life crises’ and their rites of passage (e.g. one’s choice of marriage partner, advocacy for or rejection of excision, performance of traditional rites, sacrifice) create conflicts between parents and their children. An intensive study of rites of passage became necessary, resulting in the focus of the work shifting from the conflicts to the rites themselves and their functions in a changing society.

I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to the DAAD, which created the financial conditions for the field research work, to Prof. R. Schott for his numerous pieces of advice, suggestions and information and, last but not least, to the many Bulsa informants – old and young, educated and illiterate.

PREFACE TO THE INTERNET EDITION (2023)

More than forty years have passed since the first edition of The Bulsa Rites of Passage (1978) was printed. The fieldwork for this first edition was conducted five years beforehand (1972–74). In the following period (1978–2022), I have attempted to verify or falsify my data on the rites of passage and, above all, to collect new supplementary material in addition to other major research.

The focus of my work has shifted in local terms from Sandema-Kalijiisa-Yongsa to Wiaga-Sinyansa-Badomsa since the late 1970s. In the beginning, the gates to the Badomsa compound, Adeween Yeri or Asik Yeri, had been opened to me by my long-time friend, Mr. Leander Amoak, the head (yeri-nono) of this compound (yeri) and a large lineage segment. After Leander’s death, Anamogsi of Anyenangdu Yeri (Wiaga-Badomsa) had become a more than sufficient replacement. During my 15 stays (1972–74, 1978, 1981, 1984, 1986, 1988–89, 1991, 1994, 1997, 2001–02, 2002–03, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2011) in Bulsa and my stay in Accra (2012) for archive work, I always maintained contact with Anyenangdu Yeri. I was thus able to research and observe all kinds of activities unrestricted. After 1984, I occupied my own courtyard (dabiak) in this compound, and a wife of the compound head, Anamogsi, prepared hot traditional meals for me. Although the focus of my work after 1974 shifted to other topics (e.g. the earth cult, divination, material culture, language studies for a dictionary), during my time as a resident of the compound, I was involved in everyday life while being permitted to observe the ritual life of Anyenangdu Yeri and its more-or-less related neighbouring compounds (Atinang Yeri, Atuiri Yeri, Angoong Yeri, Abasitemi Yeri, and Akanming Yeri).

While working on the data collected there for a new edition of Rites of Passage, a problem arose in how to link the new results with those of the first edition. This and my remaining time and health prompted my decision to forego writing an entirely new book, which would involve merging the data of each field visit into a homogeneous work, instead of supplementing my 1978 dissertation with new data and findings. Later surveys have substantively confirmed the results of my initial field research, further justifying this choice.

When I was seeking a topic for my dissertation and was making plans for a basic structure (after 1972), a problem arose. Initially, several key rites of passage – birth, maturity, marriage and death – were intended as the work’s focal points. Although I was able to collect extensive material on the latter sub-theme at that time, crucial data were still missing; thus, a complete understanding of the function and meaning of all rites in their chronological sequence was unfeasible. Furthermore, by including a chapter on death, the extensive presentation and analysis of the existing material would have gone beyond the scope of a dissertation.

With the agreement of my doctoral supervisor, Prof. R. Schott, I thus chose to omit the rites of passage associated with the death of a human being in this work, reserving them for a later monograph in the form of Goody’s Death, Property and the Ancestors (1962). When that plan also failed because of a preoccupation with other topics and publishing works on them, all that remained was to make an insertion in the second (Internet) edition of The Bulsa Rites of Passage. However, a fully formulated chapter was no longer possible here due to my age (86) and health. The sub-chapters on the celebrations of the dead may thus seem more like an articulated collection of material than a thorough investigation. However, this shortcoming could be somewhat compensated for by some essays in the appendix of this study.

Crafting the second edition of this work unearthed new questions. How far should the identities of the acting persons and my informants be withheld for reasons of data protection? Should their names be omitted, shortened or replaced by a pseudonym? When writing the first edition of the text (before 1978), I perhaps approached this problem with insufficient concern. The description and analysis of my field research data were primarily intended to meet the demands of an examination thesis, not necessarily for broader publication. I did not know or anticipate whether my dissertation would be published or if any Bulsa would ever come into possession of this German-language text and then study it more closely. Today, however, the situation differs substantially. Bulsa men and women have studied in Germany, are deeply interested in the traditional culture of their ethnic group, and can readily translate a digitized German text into English with a translation program (e.g. from Deeple or Google Translate) available on the Internet. Therefore, in the new edition, I have shortened or modified many names or chosen alternate names from the many names of the Bulsa persons concerned that are less known in their social environment. I have also omitted photos of recognizable people participating in rites of female excision or adultery (kabong). Other names and described actions remained unchanged if I received explicit permission or consent to publish them. For example, Anamogsi, the head of Anyenangdu Yeri (my research’s local focus), explicitly permitted me to publish unchanged names and events from his compound and the neighbouring compounds under his supervision as their kpagi (elder).

Regarding the first edition’s content, I seek to correct two previous statements in this preface. In the description of the rites of female ancestor veneration, my account (Chapter V, 3b) about the fetching of the ma-bage shrine implied a connection between the veneration of female ancestors and the earth cult. When the earth, as the contents of the ma-bage pot, was fetched from the hill of the earth shrine (tanggbain), Pung Muning, it was not because the place belonged to the shrine but because the ancestress’s compound had once stood there. In addition, in stating that the tanggbain of Kanjaga has any connection with the juik (mungo) cult or that juik is even its proper name, I unfortunately adopted incorrect information to this effect without verification.

Correcting formal elements, such as those of the Buli spelling, remains more problematic. During my initial field research (1972–74) the Buli orthographic system was not yet fixed, and even today, there are often several spellings for a single term in circulation. In the new edition, I have often retained the old spelling when it is still practised today (among others). However, I have preferably used words of a different spelling if presented in the Buli English Dictionary and have adopted terms that have become officially accepted in a different spelling or where my spelling was incorrect in the first edition (e.g. Siniensi for Sinyensi). The use of the present tense for some areas, including many social and political phenomena and activities, is no longer suitable for the 2023 Internet edition of this work since it is precisely in these areas where sizeable changes have occurred in recent years.

Finally, the author is aware that the large amount of recent data used occasionally creates a patchwork of text and, thus, a sometimes uneven reading experience as an overall text. However, as the author, I did not seek to create a creative, stylistic work of art but primarily to make my numerous data and findings available in a practical form to the Bulsa and subsequent researchers of the Bulsa culture.

Page numbers of the original 1978 edition have been placed in curly brackets {…} in the Internet edition.

- Title, Contents and Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter I: Pregnancy

- Chapter II: Birth

- Chapter III: The Guardian Spirit, Naming and Names

- Chapter IV: Scarifications

- Chapter V: Wen Rites

- Chapter VI: Excision and Circumcision

- Chapter VII: Courting and Marriage

- Chapter VIII: Death and Burial

- Chapter VIII (contd.): Funeral Celebrations

- Conclusion

- Appendix