CHAPTER II

BIRTH

l. BIRTH PROCESS

[Endnote 1]

Children are usually born in their father’s compound. However, if the mother has suffered frequent miscarriages in her husband’s compound, or if the husband’s home has no suitable women who can be of assistance, the birth (biam) can also take place in her home.

If the pregnant woman is not surprised by the onset of labour elsewhere, the birth takes place in the roofless kitchen room (gbanglong [Endnote 1a], pl. gbanglongta), where blood, amniotic fluid and washing water can drain away through a drainage hole (voong, pl. voongsa) in the outer wall. For this purpose, a member of the compound digs a hole behind the drainage hole outside the gbanglong, which is filled up again shortly after birth. Outsiders are strictly forbidden to step over the draining water and the hole.

Ayarik from Zuedema reported a case where an ancestor indicated the place with the help of a snake. A snake came into his compound and crawled purposefully towards the compound’s dayiik. It was identified as an ancestor who was to be reborn in the child. The snake stayed in the room for four days after the birth of a girl and then disappeared again.

At the onset of labour, the compound head (yeri-nyono) goes to a diviner to inquire whether any mistakes were made during the pregnancy, and he may have to offer another chicken or millet water to one of his ancestors. When the contractions begin, all children are made to leave the courtyard of the woman giving birth. It is especially important that the woman’s last-born child (patiero) does not remain nearby. The men, especially the mother’s husband, also move away. Sometimes, even the husband is urged to leave the compound.

According to Margaret Arnheim, a nurse from Gbedema, the woman giving birth is surrounded by male and female relatives and friends (nongta) until the baby crowns. As soon as the head appears, all men, young people and children have to leave the place.

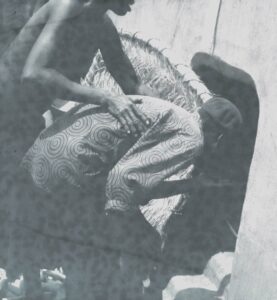

The woman is sitting on the floor with her legs spread; her hands are touching the floor behind her or are held by other women. The midwife (poi-yigro) sits in front of her [Endnote 1b]. After instructing the woman to “push as if she were going to defecate”, a helper pushes her anus inwards so that all her energy goes into the vaginal area (other information: “…so that the baby finds the right way”). This also prevents the anus from tearing. When the head appears, the baby is not pulled from the birth canal (as is done in hospitals), but the woman continues pushing (ngusi).

After birth, the baby’s head is shaped by pressure and massage (fi tag biika zuk, “one massages the child’s head”), in accordance with beauty ideals. This shaping can take place up to eight days after birth; in hospitals, it is sometimes carried out by a relative.

It is known that the placenta should not be pulled out by the umbilical cord, which can break. If even a small piece of the afterbirth remains in the woman’s body, her life is in danger. After the placenta has fully emerged, the umbilical cord is cut with a knife that has been annealed on a fire. (The reason, disinfection, is not known to most of the participants).

Reports of the birth process by other (mostly male) informants correspond to what has been presented above, although they are less detailed [Endnote 1c]. As R. Schott [Endnote 2] has experienced, the woman giving birth is so exhausted after the onset of labour that she often abandons all further efforts when the child’’s head has emerged. This exhaustion could possibly be caused by pain-relieving medicine. E. Haaf [Endnote 3], himself a doctor at the Bawku Hospital, has found that among the Kusase, this medicine often consists of a decoction of Aloe barteri [syn. Aloe buettneri, succulent plant) root. According to Haaf, this can induce early labour, but can also cause premature exhaustion of the uterus.

Among the Bulsa, after the birth, the midwife ties off the umbilical cord with a strong fibre (e.g., siek, from the pod of a dawa-dawa fruit) about 5–10 cm from the baby’s navel and cuts it with a knife or a razor blade. An informant from Fumbisi says that for a girl, the remaining umbilical cord has a length of four knots; for a boy, this is three knots. Later, when the piece of umbilical cord still attached to the child’s body has rotted and fallen off, the umbilical wound (i.e., the navel), is massaged with shea butter (kpaam) and hot water. The umbilical cord is placed in an empty shea nut shell (jigsi-kpak).

Umbilical cords in shea nut shells above the exit of an ancestral room. Some of the shells have been destroyed or have fallen out of the plaster.

Inside the dalong (in Wiaga, it is usually the ancestral room [Endnote 4]), they scratch a small hole into the inner mud wall above the exit, place the nut containing the umbilical cord into it and cover the hole again with moist mud, so that a small hump protrudes from the wall. No child is allowed to watch, especially during the latter activity.

The string or fibre used to tie off the placenta (siek, or black and red strings made of pak-grass) is kept in one of the two zamonguni pillars at the compound entrance.

The placenta (koalima) [Endnote 5] and the longer part of the umbilical cord is buried behind the compound’s rubbish heap (tampoi, pl. tampoa), as are premature babies. According to L. Amoak, the placenta and umbilical cord of female newborns are buried in the western part of the rubbish heap, while those of male newborns are buried in the eastern part. For this purpose, they are placed in a clay pot (cheng bimbili, pl. cheng bimbilisa) with a perforated bottom, which has been divided into two parts [Endnote 6]. The placenta is covered with the broken pieces of a calabash. Two women who helped with the birth carry the pot with the placenta to the tampoi, pressing the two halves of the pot together so that the afterbirth does not fall out. Beforehand, a man digs a hole behind the tampoi in which the placenta is “buried”. An informant from Fumbisi Kasiesa reported that the afterbirth is not buried in a pot, but together with the chaff of threshed millet in the tampoi. After the burial, the man who dug the hole and the women who buried the afterbirth wash their faces with water from a calabash.

Later, when grain is cultivated behind the rubbish heap, no household member whose umbilical cord and placenta are buried there eats food made from the grain. It can be used for strangers and married women or for chicken feed [Endnote 7].

The husband of the woman giving birth is usually extremely excited during the birth process and very happy after the successful birth, but he takes pains not to show his feelings. If complications arise during the birth, he runs to the diviner to find out if a mistake has been made, and he may have to make a sacrifice to a potentially enraged ancestor. However, if serious complications occur, he must assume his wife may have concealed a sexual misstep from him. Before the ash-blowing (pobsika), he must not see the child or the mother.

Additions to the notes on the birth process (2022)

In the first edition of this book, the birth process and subsequent treatments were described based on statements. In the subsequent years, until my most recent field research among the Bulsa (2011), I was never able to observe the main part of the birth process directly. However, I was often called immediately after a successful birth and was able to observe all postnatal processes and treatments at close range. These observed births are enumerated here in abbreviated form.

Births in Anyenangdu Yeri, Badomsa

26.1.89: Awunlie, Anamogsi’s daughter-in-law, gave birth to a baby girl.

5.7.94: Ayabalie, Anamogsi’s youngest wife at the time, gave birth to a baby boy.

5.3.05: Anamogsi’s daughter-in-law Assibi (Kasena) gave birth to a baby girl.

7.3.05: Anamogsi’s daughter-in-law Esi, Aleeti’s wife, gave birth to a baby boy.

Of the four observed births, the most detailed observation was that of Ayabalie’s case (see below).

Birth in Akanming Yeri, Badomsa

11.12.88: A woman from another Badomsa compound gave birth to a boy in Akanming Yeri. The woman chose this place of birth because no suitable midwife was available in her own compound. Akanming’s first wife performed the midwifery services.

Births in Wiaga-Sichaasa

4.12.88: A woman gave birth to twins in a Wiaga-Sichaasa compound.

17.7.89: Twins were born in a (different) Sichaasa compound.

Anamogsi is in possession of an obstetric medicine (biam-tiim), which is not only used in his own compound. In severe cases in particular (e.g., twin births or when the placenta does not come out), he or one of his experienced sons is called to the compound of the woman in labour. I was able to accompany him on three of these visits.

Birth in Yisobsa

7.5.89: After a birth, Anamogsi’’s son was called on to remove the afterbirth.

The four postnatal activities observed in Anyenangdu Yeri are similar to such an extent that I can limit myself to one event here.

The perforated bimbili pot in which the afterbirth is later buried

On the evening of 5 July 1994, Ayabalie (then Anamogsi’s youngest wife), gave birth to a boy. When I arrived, she was sitting on the floor of a bathroom (nying-soka-dok) and immediately showed me her child, who she was holding in her arms. The umbilical cord had already been cut and the placenta removed.

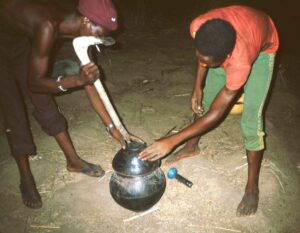

Awunlie pouring the chaff onto the clay vesses

When I arrived, the midwife Agoalie (my cook) was drilling a hole with a pointed knife in a dark bimbili pot, called a bi-yaam here. Another married woman was fetching an open basket filled with millet chaff, which was used to soak up blood from the floor.

The women (except Ayabalie) and I now moved to the rubbish heap (tampoi), where my assistant, Yaw (one of Anamogsi’s grandsons), had used a hoe to dig a hole about 40 cm deep for the pot with the placenta. They poured the bloody chaff on top of the clay pot and covered it with ashes from the tampoi. Next, they trampled the filling with their feet and washed their hands, feet and faces over the gravesite. Children from the compound who tried to approach the gravesite during these actions were sent away.

Awunlie bathing Ayabalie’s child. The end of the umbilical cord is visible.

Shortly after 8 p.m., Awunlie, one of Anamogsi’s daughters-in-law, was sitting in Ayabalie’s bathroom with the child on her feet. She poured hot and cold water from separate pots into a third pot, mixing the bath water to an appropriate temperature. The baby’s head, body, genitals and buttocks were washed with curd soap. The child cried only a few times during the bath, but otherwise remained completely quiet.

Tying the umbilical cord with a siek fibre.

Awunlie tied off the umbilical cord, already shortened to about 10 cm from the skin, with a siek fibre soaked in water. The tied piece will later fall off by itself. Ayabalie rubbed the child’s navel with the dry, crumbled leaves of a small bogta plant and then fetched a mat and spread it out in the interior of a square building. This is where she and the baby slept at night.

Rubbing the black pobsika medicine on the woman and the child.

Anointing the newborn baby on several parts of the body (photo from Akanming Yeri).

On 31 July 1994, an unmarried daughter of the house (aged around 12) led the baby from the compound to the pielim for the first time. No further birth rites took place.

The other birth rites observed in Anyenangdu Yeri differed only in insignificant details from those described above. Aleeti’s son, born on 7 March 2005, was given a small bow with a wooden arrow (see below for more information on this ritual). A woman pierced both earlobes of the newborn daughter of Anamogsi’s son Awentemi and his wife Assibi (Kasena) for earrings (2005). This custom is optional and perhaps not very old so soon after birth.

After Awunlie’s birth, Akawai (Anamogsi’s eldest daughter, who had also performed the poi-nyatika ritual on the pregnant woman) acted as midwife. In most compounds, but not in Anyenangdu Yeri, midwifery is taboo for a daughter of the house.

As mentioned earlier, Anamogsi’s services as the owner of the biam-tiim are called upon beyond his own section for births with certain problems.

On 4 February 1988, I accompanied Anamogsi’s son Atoa, when he travelled to Sichaasa to treat a woman who had given birth to twins. When we arrived, the woman was sitting on the floor of a square house. In front of her lay the bloody placenta, still connected to the two children by the umbilical cord.

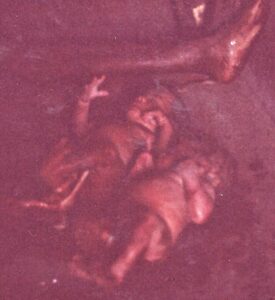

The newborn twins in Sichaasa. The umbilical cord is visible.

A large, not quite new calabash bowl without knobs was filled with fresh water and Atoa added a small bundle of tinangsa medicine to it.

Calabash bowl with tinangsa medicine.

He moistened his hand with this water and smeared it on the woman’s hair, on the place between the two breasts and on her back. The rest of the water was kept. Then Atoa pressed on the woman’s still-thick belly and a light, bloody mass emerged.

An older woman, probably the midwife, fetched a piece of barked wood from a shea tree and cut the umbilical cord with a razor blade at a distance of 5–10 cm from the navel. It bled slightly and the baby, who had been quiet until then, cried a little. The umbilical cord and the placenta were placed in a medium-sized cheng pot that already had a hole in the bottom. The pool of blood in front of the woman was soaked up using millet chaff and sand, and everything was deposited in a large calabash bowl. With this calabash and the cheng pot, Atoa, the midwife, a young helper and I moved to the foot of the tampoi, where a boy of about 16 had already dug a hole with a hoe. The clay pot, now covered with a ceramic shard, was placed inside the hole and covered with the bloody chaff. The midwife and the young man trampled on the big calabash bowl with their feet, placed the shards over the cheng pot and filled the rest with earth (or ashes from the tampoi?).

The midwife, the young assistant and the gravedigger washed their fingers with clear water from a knobbed calabash. Then they joined hands and danced around the gravesite in a kind of circle dance. This dance expressed their joy at the successful birth, but was not obligatory.

Dance around the grave site.

When Atoa and I were about to leave, we were called back for the pobsika. Only the child born from the same mother immediately before the twins was taken into the woman’s room for this step. A man covered his own eyes and blew the ashes towards the woman himself.

A few days later, deputies from the Sichaasa compound visited Anyenangdu Yeri to give thanks with a chicken and to purchase more medicine. More offerings of millet beer were made later at Sichaasa, but I was unable to observe this.

Thus, only successful births with a smoothly removed placenta have been described here. However, on 7 May 1989, Anamogsi (or his son Atoa) was called to a Yisobsa compound because of problems with the removal of the placenta. When Atoa and I arrived at the compound around 7 a.m., the woman in labour was sitting in the dalong in front of a drainage hole (voong) with a large pool of blood in front of her. I immediately noticed her skin had a grey-brown tinge, as she had lost a lot of blood.

Atoa’s first ritual medical acts were similar to those in Sichaasa (see above) – he put his medicine bundle in a calabash containing clear water and poured the water over the woman’s head several times, gave her the calabash to drink from and rubbed her belly with the water. The baby received similar treatment. Then Atoa rubbed and pressed the woman’’s abdomen more vigorously and pulled gently on the umbilical cord. However, only clear water came out and she vomited. I went to the infirmary at the Wiaga Catholic Mission Station and asked for help. They were very annoyed, because they were always asked for help when traditional medical treatment had already failed. When they refused to visit the compound, we went to fetch Anamogsi himself. He spat lightly into his hands and held the woman’s head while others boiled the medicine roots. The previous procedures were repeated: pouring the water over her head, drinking and rubbing and pressing her belly. Anamogsi also tapped the calabash on the woman’s head. Millet porridge with peanut sauce was brought for the woman, which she finished.

When there had still been no positive change around 12 p.m., I transported the woman, her husband and the child (with the umbilical cord still attached) to the Catholic hospital ward on the back of my pick-up truck. Hospital staff cut the umbilical cord but indicated that only the Navrongo hospital could offer further help. However, I would have to expect that the woman would die on the way there. Although my car battery was very weak, I allowed myself to be persuaded to drive. However, I took Stefan Völker, a German nurse, with me from Sandema. At the hospital in Navrongo, the doctor was unavailable at first, but a group of student nurses attempted to help. After a few minutes, I heard some loud screams from the operating theatre. The nurses had successfully removed the placenta manually. The woman and the baby, as well as her husband (a potential blood donor), stayed in the hospital for several days. Later, the happy husband appeared at Anyenangdu Yeri. Anamogsi received full payment for his work. Afterwards, he and I each received a dark-coloured chicken and a goat as gifts.

2. STRINGS AND AMULETS

a) Strings and fibres

After a normal birth, the mother often places simple, braided black strings around the neck, wrists and ankles of the newborn child. If one is torn, the mother replaces it without any rituals. When the child is able to walk a little, the fibre strings are replaced by a thin waist ring woven from grasses, which boys of pastoral age (about five and older) later replace with a thicker grass ring woven from eight or more strands. These grass rings are undyed, black and white or black and red. Nowadays, many Bulsa boys wear leather waist strings (chia-poala), often with attached charms (tiim, pl. tiita). However, like most coloured leatherwork, they were probably influenced by Frafra types. If older youths and men still wear a waist string at all, it will be made of leather and will usually contain charms. Girls wear thin straw strings (miik, pl. miisa) around their hips all their lives, usually coloured black and purple [Endnote 8]. The requirement for these strings to be wrapped around girls’ hips exactly four times did not always correspond to my observations.

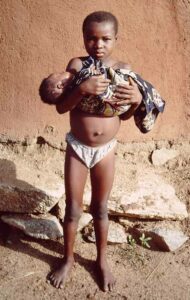

In the case of premature birth, the living boy or girl is given a special string on the third or fourth day, which is worn by the infant like a type of braces (cf. Fig. 7). A circular blob of sifted, muddy black earth (bagta) is applied to the child’s chest, below the nipples, and allowed to dry on the body. During baths, care is taken that the earth does not dissolve. It should keep the child healthy and, above all, make breathing easier. The strings and the earth remain in place for about a month.

It is rare to see a young child’s waist or neck string completely devoid of charms and remedies (tiim, pl. tiita). One of the most common attachments to the string is the guli medicine (pl. gula), also called sinsan-kuna or sinsan-gula [Endnote 8a]. The hollow parts of this plant can easily be strung on the waist string, often in conjunction with some beads. This medicine is supposed to help against stomach complaints, but the names of the medicine (sinsam = urine, guli perhaps related to guli = to vomit) also suggests other possible effects.

Lamisi, the son of the compound head Ayomo (Abasitemi Yeri), born on 23 March 1989, wore purple paksa rings around both wrists and around his left foot on 5 April 1989. Around his neck, he wore a thicker string braided from many strands, and a twisted fibre string (not from paksa grass) around his hips. This was connected to the neck string by another string. According to Ayomo, this string construction was meant to prevent the neck from buckling.

b) Amulets

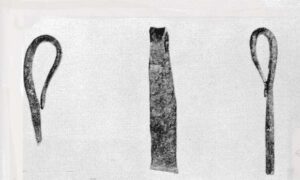

Two small iron amulets are used against worm diseases. They are made by the blacksmith and can be bought at the market – just like the guli medicine. The amulets have the following shape:

Kanaadi/ngiri bage

Nientik/ neantik

– The kanaadi amulet, which other informants also call ngiri bage (neck horn, neck “shrine”), is always worn around the neck by boys and girls. According to L. Amoak, it represents a worm. The neantik or nientik amulet (nienti = to stretch) is worn on the waist string by children of both sexes and supposedly represents the child’s spine bent in pain, as this is where worms are suspected to be. Doubts are often expressed about whether worms cause the symptoms of illness requiring the amulets, and some Bulsa speak of rheumatism. However, some school leavers do not doubt the therapeutic effect of these amulets. My first assumption that these amulets, which are always worn together, are male (kanaadi) and female (nientik, neantik) sex symbols could not be confirmed by enquiries.

Amulets, or “jujus”, are more often worn around the neck by adult women, and on the waist string by men. More recently, decorated leather pouches without charms, worn around the neck, have also become fashionable among men.

In many amulets, the material itself, or a power inherent in it, probably has a healing and preventive effect without a sacrifice being necessary. The amulets described below represent only a small selection.

– A white shell amulet must be worn if the baby vomits after breastfeeding or drinking water.

A child with a tinang-bage amulet, which has been given to him in place of a medicine horn after a segrika ritual (chapter III).

– The tinang-bage is a piece of root that is fastened around the neck with a thread so that the cylindrical wood hangs horizontally. Such amulets are quite often found on ancient terracotta objects, such as those excavated among the Koma to the south-west of Bulsaland. They may be root pieces of various plants with different healing properties. The compound head Ayomo (Abasitemi Yeri) looks for such roots under a crossroads, while the type of tree does not matter. Most of the children in his compound wear such amulets.

Amulet with a piece of skin from a monitor lizard.

– The waaung-piak or waaung-kieri amulet is made of a piece of monkey skin and/or monitor lizard skin and is said to help prevent a stiff neck.

– One or more coins on a neck-string are probably meant to provide prosperity.

– Strung tubular sinsanguli pieces help against stomach complaints (see above and figure 5).

– As described below (II, 5e), a metal moon amulet (chiik) is placed around the neck of children born on the new moon. However, other occasions exist for wearing such amulets. In Anyenangdu Yeri, a small child wore two moon amulets because supposedly, two moons had been in the sky at birth.

3. MOTHER AND CHILD AFTER BIRTH

a) Food for the mother

In the evening after birth, a porridge made of sorghum (zamonta) is prepared for the mother, called biik siuk (the child’’s navel). The mother keeps a handful of the porridge and gives the rest to all the children in the compound to eat.

In the first weeks after birth, the woman should drink plenty of hot water with millet flour, as this stimulates milk production. Cold water, cold food and cereals other than millet are forbidden during this period. The advice to eat a great deal of katuak soup and guinea fowl meat have already been mentioned (p. 42).

b) The mother’s behaviour and condition (a+b: see above)

A few weeks after birth, the young mother, who is now called pu-kogi (kogi or kong, weak) should not work hard. For example, she should not cook and should not walk far (e.g. to the market). Until the child is weaned about three years later, the woman should not have sexual intercourse. If she becomes pregnant again before the third year, her husband in particular will have to put up with people’s ridicule for not giving his wife time to raise the infant. However, if she becomes pregnant again after three or more years, it is called a “horse birth” (wusum-biam).

Ayabalie breastfeeding her son at a later stage (he is already wearing the segrika horn).

c) Breastfeeding

Although milk is sometimes produced in the breasts before birth, the mother does not breastfeed her newborn for three days after the birth. She either squeezes the bitter fluid out of her breasts or holds her breasts so that it flows out on its own.

In the past, the breastfeeding period extended until the birth of the next child (i.e., about three years). For the last child, it was often much longer, so that even a child who wanted to go to school without breakfast was breastfed once more. It is believed that breastfeeding creates a particularly close relationship between mother and child.

No real taboo exists against other wives of the same husband breastfeeding another wife’s child (e.g., if the baby’s mother goes on a trip without a child), but many young mothers are suspicious and fear these women will harm the child out of envy. Occasionally, the husband’s mother also takes her daughter-in-law’s child to her breast; if this happens frequently, it is said that milk even forms again in her otherwise empty breasts.

d) The child’s bath

I was able to observe the bathing of a child immediately after birth and later in several compounds without noticing any significant differences.

The first bath after birth is usually not carried out by the young mother but by the midwife (poi-yigroa) or an older woman in the compound who has previously washed the woman in labour (nowadays with curd soap).

To ensure that the bath water is the right temperature, the woman pours almost boiling water and cold water from two different clay pots into a third one. According to information from Akanming Yeri (Badomsa), some hare droppings are added to the first bath after birth throughout Bulsaland to prevent the child from coughing.

The midwife or older woman sits on a small stool (zukpaglik) and places the child on her right leg. Before the bath, she gives the child a drink from the bath water, administering it with her right hand (tugli).

In Abasitemi Yeri (Badomsa), Alatinbe, the eldest wife of the compound head, rubbed the child’s back with shea oil and rinsed it off with warm water. Then she poured water over the child’s head. The nose was rubbed intensively and cleaned by blowing into one nostril [Endnote 8b]. The old woman cleaned the child’s anus particularly intensively by rubbing it with oil and pressing a wet cloth into the anus several times. Then she laid the child on its back across her legs, dried it with a cloth, held it up and blew into the child’s navel, either to clean or dry it. A young girl handed Alatinbe a very small calabash bowl containing a medicinal liquid she had scooped from a bimbili on the fire. During the tuglika that followed (which was the only activity I was not allowed to film), the baby’s head lay between Alatinbe’s knees. She poured liquid from the small calabash in her right hand into the child’’s mouth (tugli). Finally, Alatinbe and the young girl dressed the infant in a woollen garment [Endnote 8c], and Alatinbe brought the child to the mother.

e) Restrictions and requirements for the child

The child’’s hair must not be cut for about two years. In addition to the mother’s milk, for roughly a year the child should drink only water in which medicinal herbs have been soaked.

A man who has had sexual intercourse with a widow before her husband’s funeral is not allowed to see a newborn child. If he does so by mistake, he spits into his hands and holds the child’s head with them.

4. RITES AFTER BIRTH

a) Robert Asekabta’s pobsika

Note: The ritual of ash-blowing (pobsika) has already been mentioned in the context of birth processes (Ch. II,1; Supplements). The following text (from the first edition) contains general remarks on the ritual of ash-blowing and a description of the only pobsika I observed before 1978.

Soon after birth, but not always on the same day, the husband of the woman who gave birth visits his parents-in-law to inform them officially of the successful birth. He can go empty-handed; only if the wife has died in childbirth does he have to bring them presents [Endnote 9]. At such a notification of the parents-in-law, which I was able to attend, it was already discussed when the pobsika rites could be performed. These rites do not involve any festivities and last only a few minutes, but performing them is of great urgency. They are also strictly observed by many Christians.

Robert waiting behind the compound until all preparations for the pobsika have been made.

Robert blowing ashes through the entrance door of the dalong towards T., while his sister is covering his eyes.

Thereafter, T. hid with her child and a young woman in the dalong (here, a large oval building), the door of which was closed with a straw mat (tiok, pl. toata). It must not be a wooden door). Then we went into the courtyard. One of Asekabta’s wives was supposed to cover Robert’s eyes, but as she was not at home, Robert’s elder sister did it. Robert had previously obtained some ash from a fireplace, which he held in his left hand. After making sure his wife’s eyes were closed and that she also held ashes in her hand, Robert’s sister led him to the front door of the dalong. His sister removed the mat (cf. Fig. 9), and the two spouses blew the ashes towards each other. Although it is often said that one must blow four times for a female birth and three times for a male birth, this was not observed here; all persona blew until their hands were empty.

After this, the partners opened their eyes. Robert entered the dalong and took the child in his arms, thereby accepting him as a new resident of the compound and as his own child.

After the pobsika, Robert took the child in his arms thus acknowledging his paternity.

In the afternoon, when Robert’s father, Asekabta, came home from a funeral, he also blew ashes with T. However, he did so completely without a helper, as he had supposedly done it so often that he did not need one help. Then, at the entrance to the dalong, he also took the child in his arms for a short time. Asekabta did not mind me watching and asked in amazement why I had not taken (more) photos.

After this, Robert and I drove to Balansa to visit T.’s biological father (her mother was staying in southern Ghana) to announce the birth officially and bring him to Asekabta’’s compound for the pobsika. However, he preferred to come later, perhaps because he feared my presence. T.’s daughter, about three years old, from a premarital union was also part of his household. Immediately after the birth of this child, T. blew ashes with her own parents (and possibly those of the child’s father). Although it is customary for ashes to be blown only on a woman’s first-born child, in 1974 they had to perform the rite again for her first child in Asekabta’s household. However, the pobsika rite will not be performed again for T.’s and Robert’s next child in Asekabta Yeri. On 20 August, I learnt that T.’s father and eldest daughter had also blown ashes with T. in Asekabta’s house. Her mother would make up for what she had missed as soon as she returned from the south.

As several informants have confirmed, sight taboos of the pregnancy period and those after a birth must be strictly separated from each other. The taboo relatives of pregnant women are identified by the diviner, and often the wena of ancestors are affected by this taboo. After birth, there is a mutual taboo of sight between the woman who gave birth and a certain group of living peoples, who are already known before birth without a diviner’’s visit. Until the birth, the woman can see these people without restriction.

However, no general clarity seems to exist on the question of which people belong to this group, and there also seem to be local variations. Most informants agree that the husband of the woman who has given birth belongs to this group, although an informant from Sandema-Balansa claims the husband only blows ashes if he has not had a child with another woman. Most Bulsa also seem to agree that after childbirth, a woman must blow ashes with her own biological parents; however, many consider it unnecessary for the woman to blow ashes with her in-laws as well, while other informants from different parts of Bulsaland (e.g., Fumbisi) claim the woman must also blow ashes with her next youngest sibling and her husband.

The pobsika rites usually take place on the third or fourth day after the birth of the male and female child, respectively, but the example from Asekabta’s compound (five days!) shows this is not always followed strictly, especially if the birth took place in a hospital. In such cases, many Bulsa consider it necessary to perform the pobsika rites in the hospital before the husband sees his wife there (cf. chapter II, 8; p. ).

According to other information, during the ash-blowing rituals, the two partners repeat these words three or four times: N nya fu (I see you). Some informants claim the young mother does not blow ashes for herself but on behalf of her child. This view is supported by the fact that pobsika is only performed when the newborn child survives the birth.

b) Ayabalie’s pobsika and applying black crosses

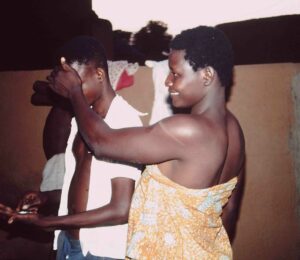

On July 7, 1994, two days after Ayabalie had given birth to a boy (see ), I was called for the ritual of blowing ashes (pobsika) before 6 a.m. The first pobsika had taken place right after birth between the baby and the next oldest child (patiero). Ayabalie and her child were still in the square building of here courtyard, the door of which was locked The ash-blowing took place, similar to the description above in Asekabta’s compound (Sandema), through the half-open door between Ayabalie and Aleeti, Anamogsi’s son who was experience in ritual matters. Awunlie, Anamogsi’s daughter-in-law, covered Aleeti’s eyes.

Aleeti blowing ashes towards Ayabalie. Awunlie is covering his eyes.

Aleeti has pulled a stalk from the thatched roof of the kusung and handed it to Ayabalie.

Ayabalie placing the rest of the white ashes on an ancestral shrine.

Then Aleeti and Ayabalie went to the front yard (pielim) of the compound. Aleeti pulled a stalk of millet from the thatched roof of the kusung and handed it to Ayabalie. She placed the rest of the white pobsika ash on an ancestral shrine (possibly belonging to Aluechari).

Back in the courtyard, Ayabalie sat down with her baby once more on the mat inside the square building. Before, Aleeti had used a pebble to grind a small piece of medicinal charcoal in a potsherd. He added about half a teaspoon of shea butter and mixed everything.

Using this black ointment, Aleeti applied small crosses to both of Ayabalie’s feet (between the big toe and the second?), to her forehead and to her hands. Subsequently, the baby was anointed on the same body parts.

With the rest of the medicine, Aleeti painted black crosses at the following places in the courtyard:

1. above the door at the entrance to the square building (inside),

2. above the door at the entrance to the square building (outside),

3. over the entrance to the bathroom where the birth took place (outside),

4. above the entrance to the open kitchen,

5. above the entrance to a round building with a flat roof in the same courtyard,

6. above the entrance to a conical-roofed house in the same courtyard, and

7. above the cemented entrance to the courtyard (inside).

In Anyenangdu Yeri, the pobsika, the anointing of mother and child, and the application of the black crosses are usually performed by a son of the compound head. However, I received other information that actually anyone can perform these rites. The compound head of Anyenangdu Yeri explained to me that the woman giving birth does not blow ashes with the son of the compound head, but with the birth medicine from whose charred roots the ashes are made.

Specific buildings in the courtyard of the young mother (e.g., other children’s bedrooms) may also be marked with such black crosses [Endnote 11a]. These are supposed to protect the child, the mother and other inhabitants of the compound from evil spirits and ghosts.

Excursus: Blowing ashes in other situations

Bawa, the compound head of Akanwari Yeri (Gbedema-Gbinaansa), was not allowed to offer a sacrifice to a juik (mongoose shrine) until he had performed the ash ritual with a dog that had just had puppies. The dog was locked in a room (dok) and Bawa pushed the door mat aside slightly and blew into the room. His eyes were closed while the dog was allowed to see him without danger. If he had seen the dog, it would have died, but not Bawa, who was protected by a medicine. I was told that this particular sight taboo, which is lifted by a pobsika, is probably only carried out in Akanwari Yeri. It certainly plays a role that mongoose and dog are considered mortal enemies.

In Badomsa, when Ayomo, a compound head, was doing some carving work in my presence, he interrupted this activity at sunset, because it is not allowed to continue doing crafts in the dark until after he had obtained some white ash from a cooker and blown it towards the sun from the flat of his hand.

Ayomo blowing ashes towards the setting sun.

Princess Marie Louise, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria, mentioned the ritual of ash-blowing with the moon (cf. a similar ritual of the Bulsa without ash-blowing, Ch II, 5e) in her diary (1926: 116) of her travels through northern Ghana, without specifying an ethnicity,:

“…they take a little wood-ash, put it in the palm of their hand, and blow it towards the thread-like crescent, saying: ‘I saw you before you saw me’. This is to prevent their strength decreasing as the moon increases in size.”

c) Outdooring a child

The rites for taking the child out of the compound (for which the word “outdooring” is used in Ghana) is closely connected to the ash-blowing rites. The execution should take place in the early morning hours (around 4 a.m.), probably after the ash-blowing, but this time is not always adhered to. When asked who performs the rite, I received various answers: a married woman from the father’s lineage, the woman who also performed the poi-nyatika rite and, according to L. Amoak, a medicine man, whom he calls pobsido [Endnote 11]. In Anyenangdu Yeri, it is always a “daughter of the house” (yeri-lie). The child is brought out in the arms of the bearer without any special ceremonies.

The ritual of outdooring is not very pronounced among the Bulsa, and in many homes it does not seem to be considered an independent act at all, but it is said that after the ashes have been blown, the mother and child are allowed to leave the compound. Perhaps the outdooring is only mentioned (and performed?) as an independent rite by some informants because they are aware of how great a role outdooring rites play among the Akan people of southern Ghana.

The father and mother may not call the newborn child their own child before the outdooring and pobsika. The child is spoken of only as “that child” and in Buli as nichaano or chaano (stranger). As a temporary name until the official naming in the segrika, the child receives the proper name Asampan or Anpan. In some known cases, this name remains a nickname even after the segrika.

The baby being ledoutside the compound by a daughter of the house.

On 31 July 1994, Adeboalie (Anamogsi’s daughter, who was about eight years old), led Ayabalie’s son, who was born on 5 July 1994 (see above), out of the house without any additional rites. Anamogsi explained to me that only a daughter of the house (yeri-lie) could perform this act.

I observed another “outdooring” in Akanguli Yeri (Wiaga-Napulinsa) shortly before ai girl’s segrika. She had visited the kusung in front of the compound before, but she was not allowed to leave her own section for a visit to the market, until after the official outdooring. The performer was a woman from Guuta who had married into Akanguli Yeri (i.e., not a yeiiiri-lie , as in Badomsa). Subsequently, the woman and child sat down one after the other on the ancestral shrines in front of the compound (or was this already part of the segrika?).

5. UNUSUAL PHENOMENA AT BIRTH

a) Twins (yibsa; dark Buli: nisima siye, literally “two arms”)

Every twin birth, even if the twins turn out to be harmless, is ascribed to a supernatural reason and is commonly regarded as being associated with evil. Immediately after birth, the parents go to a specialist in twin births (yibsa tebro) who finds out whether the twins are harmless or malignant – in other words, whether they are kikita (sing. kikiruk) [Endnote 12]. In the latter case, he performs ritual practices in the twins’ birthplace (see Ch. II, 5b). Without protective measures in the compound where the twins were born, the mother must expect to give birth to twins again, or even to triplets [Endnote 12a].

If one of two (harmless) twins falls ill, an attempt is made to keep this secret from the other twin by moving the sick one to a distant place. If one twin dies, he is buried by the yibsa tebro at a secret place. The grave site is levelled to make it impossible for the surviving twin to discover. These measures are explained by the view that twins not only have equal dispositions, but always want to do the same thing, as their souls (chiisa) and wena are equal. If one twin dies, the soul (chiik) of the other will also want to leave the body forever when learning of the death of the other twin. Ayarik from Wiaga reports his wife had twin brothers, one of whom died a few years after birth. The surviving brother was immediately brought to Kumasi and the entrance to the Wiaga compound was moved to a different side. Even at the time of informing, the boy in Kumasi, who was about five years old, did not know his brother was dead.

When a female twin died in Amoaning Yeri (Sandema Yongsa), his sister was brought to Navrongo, and the main entrance to the compound was moved before the surviving twin returned.

Two surviving female twins are not only forbidden to marry the same man, like all other sisters who succeed each other in birth, but also ought not to marry into the same compound . However, if this happens, they must use different compound entrances. The woman who married into the compound first will use the main entrance, while the one who married later will use a back entrance or will leave the compound via a wall.

Protective rituals do not only take place immediately after birth but can also be repeated at any time in problematic cases. In one such ritual (nipok gomsika, literally “treatment of the woman”), in which I was able to participate on 9 February 1989 at a Bachinsa compound, all rites were primarily related to the mother of the twins aged 6–7, who were not included in the ritual events any more than the other participants. The rites were performed by two sons of Anamogsi (Atoa, the elder son, and Abiisi) who had brought a large number of medicinal root pieces (tinangsa) from their compound’s biam-tiim shrine.

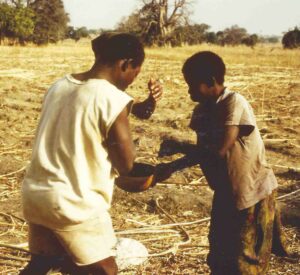

In the middle of the woman’s inner courtyard (dabiak), they erected a hearth made of three stones. The compound head poured some clear water on the ground in the courtyard and informed his ancestors about the upcoming event. Atoa placed the root pieces on the ground, cut off two toes of a brown chicken on a wooden pad and smeared each piece of root with the chicken’s blood. Then, he placed the larger portion of the medicine in a black bimbili clay pot filled with clear water. The mother of the twins took a piece of root, her hand being guided by a male member of the household (possibly her husband). Before throwing the root piece into the pot of water, her hand (together with the man’s hand), circled over the rim of the pot three times, with a fourth turn being performed by the woman alone. Then Atoa poured the remaining root pieces of the large pile into the water pot. After a short prayer, he added two dark chickens, a guinea fowl and millet beer (daam) in succession to the medicine pot, which was closed with a kpalabik lid.

He placed the roots from the smaller pile into a ceramic smoking pot (ngoadi) with many holes and put it on the fire in the three-stone hearth to char the roots. At times, he poured a handful of water on the partly burning medicine.

First the compound head (yeri-nyono) approached the smoking pot and held his hands over the smoke and steam rising from the pot. Next, I was asked to do the same. The mother of the twins held the outer and inner palms of both hands, her knees and her feet over the smoke, then bending over the pot to inhale the smoke. Other household members followed. Finally, the twins were also forced to undergo this procedure.

The twins’ mother took the remaining pieces of charred roots to her room in a calabash bowl for storage. Some men removed the sacrificed chickens to cook them. Two other men pounded the ingredients for two different sauces in two mortars: buura (the seeds of a calabash-like fruit, Cucumeropsis edulis? Egusi; Neri), tue (beans), and ngmaana (okro). After the rest of the millet beer was offered to all present, a break occurred before the completion of the following meal.

The activities continued until around 11 a.m. On a new hoe blade, Atoa grated some of the charred medicine wood using a round grating stone and added some salt and shea butter. To the clay pot with the liquid medicine in the centre of the courtyard (sunsung), he added clear water, millet porridge with sauce and meat from the three chickens. Small portions of millet porridge were smeared with the black, oily medicine and eaten by several participants (e.g., the yeri-nyono, the twin mother and the two sacrificers).

Around 12 p.m., the general meal took place, namely millet porridge with three different sauces: buura/tue, ngmaana and jum-goalik fish sauce). Subsequently, the meat from the three sacrificed chickens was distributed according to established rules (I received a guinea fowl leg).

After several speeches of thanks, the ritual acts of nipok-gomsika had been completed. As payment, Atoa and Abiisi took the following things to Anyenangdu Yeri: the bulk of the three sacrificed chickens, the new hoe blade, the live brown chicken (with two toes missing), a calabash bowl containing flour and four small musa stalks and a cheng-bili clay pot with shea butter. Just as we were about to leave the courtyard via the two tiila ladders (inside and outside), one inhabitant of the compound took white ash from the three-stone hearth and sprinkled some on each step of the two tiila.

In Anyenangdu Yeri, sacrifices were later made to the medicine shrine (biam-tiim) of the compound (which I did not observe). Here, among other things, the brown chicken with the missing toes was sacrificed. The shea butter was used for medicine preparation, the flour was distributed to the children in the compound and the musa stalks were disposed of after some time.

b) Malformations and physical peculiarities

The following physical signs indicate a kikiruk birth:

1. deformed arms and legs,

2. a strange, disguised facial expression,

3. a harelip,

4. more or fewer than five fingers per hand,

5. more or fewer than five toes per foot,

6. teeth already present,

7. hair in the armpits and on the private parts,

8. other signs of prematurity,

9. blindness, and

10. short stature.

After the birth of such a child, the parents go to see a medicine man (kikiruk paro) [Endnote 13] who specialises in such cases. He gives the parents a medicine which they administer to the child. If the child resists this medicine, it is a malignant case. The medicine remains in the child’s room and the recognised kikiruk will continue to cry, refuse all food and lose weight, finally dying. Then the medicine man returns and sprinkles a liquid medicine inside and outside the house so that no more kikita will be born in the future.

I was able to participate in such a ritual, followed by a burial [Endnote 13a]. In April 1988, a father from Wiaga-Sichaasa came to a kikiruk-paro (an owner of biam-tiim, the birth medicine which also helps against kikita) who is a friend of mine. The father described his problem.

His wife had given birth to twins, one of whom refused to breastfeed. After he had acquired and applied the twin medicine, the twin died, and the father asked the medicine man to bury his son. The latter agreed despite initial reservations. At about 9 p.m., three of his sons and I went to the twin’s compound. The deceased twin, who had an exceptionally large head, was lying on the floor of a round house (dok). The elder son sprinkled the biam-tiim medicine on the twin and on the walls of the room. After the father had removed the child’s neck-string, the eldest son placed the baby headfirst into a large clay pot (samoaning). The father showed us a shallow funnel-shaped anthill of the gusunguri ant (“black ant”, driver ant? Dorylinae?) a few hundred metres away and then withdrew. The three sons dug a hole in the anthill and placed the clay pot containing the baby inside it.

A hole is dug in a gusunguri anthill. The clay pot containing the dead child can be seen in the background.

The clay pot containing the baby is destroyed with the combined hoe-spade.

Before closing the hole, they destroyed the clay pot with their digging tools so that ants could enter the pot more quickly and destroy the corpse. Using a grass broom, the sons sprinkled the medicine-water over the whole gravesite and left the broom on the grave. At his compound, the father of the twins presented us with the obligatory gifts/payments: one goat, one black chicken and all the tools we had needed (the hoe and the medicine calabash). Later, the kikiruk-paro sacrificed the donated animals to the biam-tiim (birth medicine) in his compound. Afterwards, his three sons and I had to drink from the biam-tiim. It was completely tasteless.

The biam-tiim shrine in a corner of the first wife’s courtyard.

Adults can be characterised as kikita based on their physical features and behaviour. In Sandema-Kalijiisa (1973), an unmarried man aged approximately 40, who was about 1.30m tall, was generally regarded as a kikiruk. When he appeared in the neighbourhood, people beat him and drove him away, as it was believed that he could move the yields from neighbouring fields onto his own fields through his supernatural powers .

In his life story, one of my informants reported that as a child, he was often mistaken for a kikiruk because he spoke like an old man very early, ate “an incredible amount” and could do everything much better than his siblings. Nevertheless, he did not learn to walk until he was three to four years old. When a man came to the compound with a bicycle, the boy told his mother he could walk if he were allowed to go to the bicycle, and with a sure step he went to the bicycle all by himself. For many onlookers, this was another sign that he was probably a kikiruk.

c) Other harmless phenomena

Children born with body hair are called kobta nurba (sing. kobta nur). However, they are not kikita and are not considered to pose a danger to the family unless their armpits and private parts exhibit a hairiness.

A foot birth (tulimbaziik) is considered more ominous, but it is also not indicative of a kikiruk birth. Sacrifices are made to the ancestors and a special medicine man is sent for before the child is carried out. The medicine is carried in a broken pot or calabash and added to the bath water of the mother and baby. My cook in Anyenangdu Yeri, then about 60 years old, showed me a small earthen shrine made in her bedroom, which I had taken to be her personal wen shrine. It was a tulimbaziik–bogluk. The woman had a foot (breech?) birth many years ago (with a fatal outcome for the baby). Afterwards, this shrine was built, to which sacrifices had to be made (possibly until the woman reached menopause).

d) Children born on the same day

I know of one such case from Sandema-Kalijiisa-Yongsa. My informant Godfrey Achaw was born on the same day as his friend John from a neighbouring compound belonging to Kalijiisa-Chariba. When sacrifices are made in one compound, some of the sacrificial meat must always be sent to the other compound, although the two men of the same age are currently in southern Ghana. However, if they return for a visit, they must be informed of all the offerings. If a funeral celebration is held at G. Achaw’s compound, Godfrey must sleep at his friend’s comppound, even if John is not present. Of course, he should attend all the funeral events. If the two friends did not belong to the same section (Kalijiisa) and were not of the same sex, no marriage ban would exist between them.

e) Children born at new moon

When children are born on the first day of a new moon, a correlation is made between them and the moon. The parents hang a metal moon amulet around the neck [Endnote 14] of such a baby (see Fig. 2). After naming and segrika, the metal moon is usually worn on the same string as the naming horn [Endnote 15]. As soon as the child can speak, they are instructed to climb onto a platform roof when the moon first appears and, depending on the sex of the child, to blow ash three or four times in the direction of the visible moon. Each time the child says:

“Chiika a baling bo, N.N. a biiyo. The moon should become thinner and N.N. (name of the child) should become fatter.”

If this action is not carried out, the child will remain skinny and weak. According to some informants, the child can also get a skin disease [Endnote 16].

Iron moon amulet with fibre string

An old moon amulet, no longer used in this form today. The moon is suspended on a string dividing the sky into two parts.

Usually, the described ritual is no longer performed after a few years. However, an old man from Kubelinsa, who was also born on new moon, has worn such an amulet throughout his life, otherwise he gets sick at every new moon.

A child from Anyenangdu Yeri also wears an amulet with two metal moons around his neck, because supposedly two moons were in the sky on the day of her birth (see above).

6. DEATH AND BURIAL OF YOUNG CHILDREN

[Endnote 16a]

If a child dies at birth or shortly afterwards, the parents should not lament, otherwise this child will be born again and die repeatedly. According to my own enquiries, all stillborn children and the first live-born child who dies shortly after birth are buried in the ash heap (tampoi). Subsequent children are buried near the compound on a footpath leading to the maternal grandparents’ compound.

The compound head of Akanming Yeri (Badomsa, inhabitants from Siniensi) had all the deceased infants from his household buried in the cattle yard. As such a grave is at great risk of being destroyed and opened by animal hooves, the graves have a shaft depth of about 1m and are covered with a particularly heavy stone. The compound head is aware of the Bulsa usually burying their children outside the compound.

R. Schott received two not entirely consistent messages from different informants in 1966–1967. According to the first informant [Endnote 17], the first child that dies in childbirth is buried near the wall of the compound behind the kitchen (gbanglong) so that the woman can easily give birth to it again. If the woman later loses another child in childbirth, it is buried on the way to the maternal grandfather’s compound. The grave is dug by a gravedigger (vayiak, pl. vayaasa), and this man also buries the child without household members attending the burial.

According to R. Schott’s second informant [Endnote 18], the first child who dies shortly after birth is buried on the way to the maternal grandparents’ house. Children who are stillborn and the second child who dies shortly after birth are buried at the rubbish heap (tampoi). All subsequent infants are buried in the cattle yard [Endnote18a].

The children are buried with their sleeping mat (if they already have one) but without clothes. As a grave gift, they are given a shea nut shell full of mother’s milk. The surface of the child’s grave is marked by a piece of broken house wall or a stone. According to R. Schott [Endnote 19] it is also marked by a stone, but in any case not by a ceramic boosuk, as is usual for adults.

Children up to about four years of age never get a funeral celebration unless another child was born after them; and even if they have younger siblings, only an informal funeral is held shortly after the burial with just a few invited guests.

If the first child of a man and a woman dies, the hair on the parents’ heads is shorn on the third day (male) or fourth day (female) after the child’s death, depending on the child’s sex. When L. Amoak’s almost two-year-old son Awenawie died, the mother’s hair was shorn on the third day in the compound of her former marriage intermediary (san-yigma) [Endnote 20]. She stayed in his compound for three days and then received a guinea fowl and millet flour from the san-yigma for her own consumption. L. Amoak himself had previously lost other wife’s children by death and was therefore not shorn again. If the hair has grown a little some time after shaving strips of about 2 cm wide (naa-vuuk, pl. naa-vuuta, literally “cow path”) are shaved from ear to ear and from the forehead to the nape of the neck. The bald strips thus form a cross on the head. On this occasion, bean cakes, a dark-coloured fish (“mud fish”, Buli: jum sobli), and goat meat are eaten by the parents in a ceremonial meal (gaasika). The consumption of these “black” foods was forbidden to the parents after the death of their child .

During my fieldwork, I was able to observe the death and burial of an infant only once. On 12 October 1988, a mother from Anyenangdu Yeri showed me that her infant Akanchainfiik, who was a few weeks old, was breathing heavily and refusing to breastfeed, although she accepted clear water. Her temperature was 37°C. I immediately drove to the Wiaga Catholic Clinic with mother and child on the back of my moped. The nurse was upset that the mother had brought in the seriously ill child too late. She diagnosed a severe chest infection (pneumonia) and gave the baby two injections and extra medicine for home treatment. After a short-term improvement, Akanchainfiik died the next morning. When I returned from a neighbouring compound at 7 a.m., some men from Anyenangdu Yeri and neighbouring compounds were sitting near the outer compound wall, not far from the entrance (nansiung) under a temporary shade canopy. A silence had fallen, and all necessary utterances were spoken in low voices, though no wailing or other utterances of mourning were heard.

Anamogsi led me to the mother’s living quarters. She and several elderly women from Anyenangdu Yeri and neighbouring compounds were sitting silently on a bench outside a room (dok). A neighbouring woman was holding the dead child on her lap. I was asked to check again whether Akanchainfiik was really dead. I felt no pulse or heartbeat, and the child was already cold. Anamogsi showed me the place in the cattle yard where (according to him) the child should be buried (although she was later buried near the tampoi).

In front of the compound, Ansoateng (a neighbour and gravedigger) was busy making a spade from an unworked straight branch and an axe blade. He shortened the wooden handle of an old hoe to work in a narrow grave shaft.

When Ansoateng and two young helpers started digging the grave at the tampoi, Anamogsi interrupted them and asked them to dig at another place, as he wanted to build a kusung here later. They chose another spot farther away from the foot of the tampoi, at the edge of a millet field.

All the male guests (including me) continued to sit near the compound wall at a distance of about 20m from the grave. Anamogsi sent me to the grave, knowing I would like to observe details of the burial. The grave was about 50 cm deep, the top diameter was about 30 cm and the round bottom was about 50 cm in diameter, meaning the shaft widened downwards. In addition to the above mentioned tools, two calabashes were used for digging, when bare hands were not used for this purpose.

Two neighbouring women carried Akanchainfiik’s unclothed body together with a tuft of leaves (probably wogta) in a small sleeping mat (tiak). From that point on, the gravedigger, Ansoateng, was the only active participant. He tore off the dead child’s fibre necklace, one arm ring and the waist string and laid everything next to the grave along with the tufts of leaves. Then he placed the child in the grave so that the head faced south, with the face (at first) facing east. In the grave, he manipulated the child’s fingers and toes, then I supposed that he had twisted them. Later he told me that he had washed them off with water. The dead baby’s legs were drawn up and, the hands placed over the ears (so that no earth could penetrate them). Finally, Ansoateng laid the child facing west (had he made a mistake?). Using his hands, he threw earth into the grave and stamped it down with the wooden end of a dachoruk (spade). An assistant fetched a heavy laterite stone, with which Ansoateng tamped down the earth even more firmly, at the same time creating a shallow depression. He took the stone and made four circular movements with it over the grave before fixing it in the depression.

An inconspicuous laterite stone marking Akanchainfiik’s grave.

Ansoateng completely crushed the two calabashes under his feet and deposited the shards, together with the dachoruk and the hoe, to the west of the grave. The two iron blades were later removed from the grave implements and brought indoors. Ansoateng placed Akanchainfiik’s torn body strings and the tuft of leaves on the ground east of the grave and covered everything lightly with earth. The three gravediggers washed their hands and faces just above the grave. Ansoateng also washed his legs, pouring the remaining water on the grave.

At the outer compound wall, members of the compound thanked the three gravediggers in several speeches. Akanchainfiik’s father joined them. He was very depressed but made no expressions of grief. In the evening he came to my room (in Anyenangdu Yeri) and thanked me for my help and participation.

As Akanchainfiik was the first child her mother had lost through death, the mother’ head was shaved (barisika, “shaving”) after some time, creating a cross shape on her head (I did not observe this procedure or the result, as the mother always wore a headscarf afterwards).

7. REBIRTH

General beliefs in regarding rebirth differ among the Bulsa. Some say half-jokingly that a child is probably the reborn grandfather if the child bears a strong resemblance to the deceased. Others believe that an ancestor is reborn with every birth and that the diviner can determine the name of this ancestor, although one must not mention this identification to the person concerned under any circumstances.

Margaret Bawa reports that in Gbedema, pregnant women do not want a very old man to stand behind them, because they could easily give birth to him again after his death (ngmani, “to return”). Such children die easily and are then reborn. Children who are reborn ancestors are often pampered. For example, they are spared hard field work. If they are insulted or somebody mentions to them that they have been reincarnated misfortune can easily occur if they do not make an atonement offering to the reincarnated ancestor. Even living old men are sometimes associated with newborn children. When such an old man dies, the associated child also dies.

When an old, very popular man died in Wiaga-Tandem, white ashes (buntuem) were placed on the hair of his head before his burial. A short time later, a child was born in the same compound with white hair in the middle of the skull and black hair on the sides, in the same pattern that the ashes had been placed on the deceased relative’s head. This event is interpreted as evidence of a rebirth.

Generally no doubt exists that infants who die can later be reborn to the same mother. Especially when a woman has had many successive miscarriages or the children die at a young age, it is believed that the child or an unnameable evil spirit (ja-biok, literally “an evil thing”) is playing tricks on the woman. Through various measures, such as a specific naming [Endnote 21] or specific scarring [Endnote 22], people try to put an end to these tricks. There does not seem to be complete clarity, at least among my informants, whether the child is to be equated with the evil spirit or whether they are victims themselves. The latter assumption is probably correct, because, according to one informant, a mother wishes a deceased child to be reborn to her again.

When a child has just died, measures are taken to help the next child live longer. Shortly before the burial, one finger of each hand is placed over another, and the same is done with the toes [Endnote 23]. The next child will be born with this finger and toe position and will not die again as an infant.

According to another informant (Akoasisi from Siniensi), sometimes a child born alive after several miscarriages has a toe turned over or a toe or finger cut off. These mutilations have a similar meaning to the cutting of scars after miscarriages [Endnote 24] and are also intended to prevent this child from dying, as the “evil spirit” will not recognise the mutilated child and will leave it alone.

A woman in Wiaga-Tandem frequently had children die. After another birth, a married-out “daughter of the house” came back to her parents’ compound, put the living child on the ash heap (tampoi), and scattered ashes from the tampoi on the infant. After this, no more of this woman’s children were believed to have died. Possibly the latter act is intended to feign, a burial to make the evil spirit believe that the infant was dead. s

The feigned sale of a child born after several miscarriages (kpi-le-ngman-jamdoa, “returner”) is apparently traditional among the Bulsa. However, some Bulsa in Accra seem to have adopted this ritual from other ethnic groups. In one known case, a Bulsa woman “sold” her newborn girl to a Zambarima man in a basket and named her Azambaring. The child was immediately returned to the mother, as she had to be breastfed. The purchase price is very small, for example three pesewas (sampoak), after which the child may also be called Asampoak. I have also heard of the feigned abandonment of such children in the bush (sagi) in connection with naming the child Asagi.

I received the most detailed information about rituals and customs after rebirth from Margaret Bawa (Gbedema). This includes some individual information provided by others. When a child dies for the third time, the following rituals, or a selection of them, are performed:

– One toe is placed over another.

– A toe is broken and bent inwards.

– Red clay (junung, daluk) is smeared on a spot on the arm, thigh or face; upon rebirth, these areas of skin will be lighter.

– In one spot on the head, hair is pulled out; the child is reborn with a bald spot on the head.

– White ashes are placed on one part of the hair; the newborn will have white hair in this spot.

– The upper part of the ear is bent over.

Mostly, it will not be necessary to give the child additional derogatory names (slave names, see below).

Before a woman has lost her third child, she should not weep for the death, otherwise the child will think it is wanted and will always return. After the death of the third child, the mother may cry, because the above mentioned mutilations are sure to have an effect. The mother of my informant did not know of any case of child rebirth after these procedures.

When a mother dies with her unborn child, the embryo is pressed out of the dead woman’s womb to see whether it has the above marks or mutilations. If this is the case, the markings were the cause of death, because the child would have had no possibility of return after birth.

8. ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIOUR AMONG THE STUDENT GENERATION

Pupils and school leavers are often said to engage in premarital sexual intercourse more frequently than their illiterate peers. That most schoolchildren are aware of contraceptive measures and that contraceptives are accessible to some extent is seldom disputed. Pregnancy is often not desired because it jeopardises school or professional careers. Nevertheless, most pupils wish to have a large family with many children later on, and it also means unimaginable shame for schoolgirls if they are found to be infertile [Endnote 26].

Abortions are said to occur from time to time – although very rarely – but I know of only one case of a married school graduate. I could not confirm her motives definitively, but it can be assumed that she was afraid of giving birth. In no way did emancipatory thoughts play a role (at that time), because as a schoolgirl, she had undergone excision and had given me a report of her excision shortly before her second, fatal abortion attempt.

The younger generation does not differ from older generations so much in their attitude towards birth and the blessing of children, but they differ more in their attitude towards the restrictions, prohibitions and ritual acts associated with pregnancy and birth. The food prohibitions listed above [Endnote 27] are regarded as nonsense, and as they learned in their hygiene classes at school, the pregnant woman should be given food rich in protein.

However, a young Catholic school graduate, reported that she had never eaten food from the previous day during her pregnancy, but she had not observed all the other rules.

The water-pouring ritual (poi-nyatika), which precedes the public announcement of the first pregnancy, is still performed by some school graduates. A school-educated relative is often brought in to perform this ritual, as she will later have a great influence on the firstborn child if it is a girl. Some Christian Bulsa recognise the Christian blessing of the pregnant woman, and the public announcement of the pregnancy in church as a full substitute for the traditional ritual, which they call a waste of time. However, care is usually also taken not to mention the pregnancy in the presence of the pregnant woman before the church announcement.

The date and day of birth is carefully written down by the literate father, and even many illiterate fathers today asks a housemate to write down the date of birth of their children. In recent times, the registration of all births at the Health Centre [Endnote 28] is required by the authorities [Endnote 29].

If the educated young father can afford the two or three cedis (about €2.5) for his wife’s hospitalisation, his wife will have her child in the hospital (e.g., at a mission station or the Sandema Health Centre). Today, some illiterate fathers also send their wives to the hospital to give birth.

Difficulties may arise in performing the rites during the first days after birth. Pobsika rites are now often performed in the hospital when the spouse or parents enter the mother’s hospital room for the first time. The ashes are often provided by the nurses from their own hearth.

Christian parents have their children baptised, but often only several months or years later. It would be worth investigating whether the act of baptism is also performed in response to illness or difficult behaviour from the child, as is the case with the traditional naming or wen-piirika ritual. Baptism is associated with Christian naming, and in Sandema, for example, the Presbyterian missionary or a catechist suggests several English names from which the father or the adolescent baptismal can choose.

The killing of “fairy births” (kikita) and twins is rejected by Christian parents in particular, who mostly even welcome twins, as is also often the case for non-Christian parents. Nevertheless, certain children in some schools are considered kikita by the rest of the students due to their physical stature or behaviour. By no means are they completely shunned, because “it is not their fault that they are kikita”, but neither can cordial friendships develop, as these pupils are often secretly feared. “Twins are mostly harmless these days,” a school graduate told me. Nevertheless, stories circulate in student circles about a pair of evil twins, two brothers who now live in the south after leaving school early. Moreover, it seems that twins themselves often do not know they are twins, and some twins’ official dates of birth differ by one or two years, while others are even passed off as the children of different mothers.

ENDNOTES

CHAPTER II: BIRTH

1 In Buli, the verbs biagi or vuugi mean “to give birth”. The latter also has the meaning “to live, to survive”. The question to a spouse, “Fi poowa an diem vuug-ya?” (Has your wife given birth yet?) is only allowed if the wife is already pregnant.

1a A birth that does not take place in the gbanglong often has implications for the name of the newborn child. (Cf. chapter. III B, 3b)

1b A woman who is particularly experienced as a birth attendant may be called poi-yigro (poi = belly; pregnancy; yigro = catcher, someone who catches something). Less experienced helpers may be called maariba (sing. maaro; maari = to help) or tabriba (sing. tabro; tabri = to handle carefully).

1c Therefore, the corresponding texts in the first edition have been omitted here.

2 Diary entry from 30 December 1966.

3 Die Kusase, p. 81 f.

4 Cf. site plan, chapter V.

5 Koalima (pl.), also has the meaning “goods, cargo, burden”.

6 Cf. E. Haaf, Die Kusase, p. 83 .

7 Inf. G. Achaw from Sandema-Kalijiisa.

8 Cf. chapter I, 3, p. and chapter. I, 5.

8a Guli, pl. gula, sp. bush grass used for making items such as busik-baskets, fish traps and drinking straws.

8b The Bulsa differ here from some neighbouring ethnic groups (e.g., the Frafra, who suck out the baby’s nose).

8c Young Bulsa boys and girls wear clothes that are open at the bottom to allow unhindered defecation. Faeces are immediately consumed by a summoned dog.

9 Inf. by R. Schott, Unpublished Field Notes 1966/67, p. 224.

10 I was told that exactly four days had passed since the birth of the daughter (on 8 August) (four: female principle). Four days is the norm.

11 Pobsido is the nomen agentis of pobsi (to blow ashes); pobsika is verbal noun of pobsi.

11a See D. Tait, The Konkomba of Northern Ghana (London, 1961), p. 200. For an illustration, see R.S. Rattray, The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland, Fig. 87 (after p. 380).

12 Kikita are demons with superhuman powers who usually appear in human form. Cf. Conclusion, 3 of this work and R. Schott, Aus Leben und Dichtung… (1970) , p. 60ff. Of the two variants kikiruk and chichiruk, kikiruk is used mainly in Wiaga, Siniensi and in the southern parts of the Bulsa country, while chichiruk is used mainly in parts of Sandema and in Chuchuliga. Kikiruk is said to be the original Buli word, with chichiruk being perhaps a borrowing. Do not confuse kikerik (pl. kikerisa) with kikiruk (pl. kikita). Kikerik is a spiritual being that never takes human form.

12a L. Fleischer (1977: 104) assumes for the Hausa that the rejection of twins is based on the fact that their seniority may be questioned. Among the Bulsa the one born first is considered the younger one, sent ahead by the older one. Twins of different sexes are also considered less dangerous.

13 My informant, the teng-nyono of Wiaga-Sinyangsa, is both yibsa-tebro and kikiruk paro (Cf. pari, to seize).

13a For a more detailed description, see Kröger 2019: 83–85.

14 Such a moon made of sheet iron should always have a ribbon from which to hang it, and even in the market, it can only be bought with an attached fibre cord. It is believed that the moon is suspended in the sky; therefore, its image should always have such a ribbon from which to suspend it. Cf. fig. 2.

15 Cf. chapter III, 1 and Kröger 1984: 149–151.

16 See also E. Haaf, Die Kusase, p. 90 and F. Kröger 1984: 149–151. Ash blowing (Buli pobsika) with the moon, as described by Princess Marie Louise (1926: 116), is not known to the Bulsa (see also chapter. II, 4,a).

16a According to the 1960 Population Census of Ghana (vol. 6, p. 313), infant mortality among the Bulsa is particularly high in the first four years of life. Within one year, the following death cases were recorded for the Bulsa (absolute numbers): under 1 year: 520; 1–4 years: 300; 5–14 years: 80; 15 years and older: 20.

17 Unpublished field notes 1966–1967, p. 185.

18 Ibid, p. 225.

18a I received the following information by letter from L. Amoak shortly before the completion of this work (1978): The first child born to a mother at a very young age (under one year) and children born in an embryonic, non-viable state are buried in the tampoi. Other children born alive are buried along the footpath to the mother’s home. Children are never buried behind the kitchen (gbanglong). My informant himself had two sons who died at a young age. The first was already over a year old and was buried at the footpath “as he was already too old for the tampoi”. The second son died shortly after birth and was also buried at the footpath.

19 Unpublished field notes 1966–1967, p. 185.

20 Translated by L. Amoak as “middle-man”; “sin/san”: short form of sunsung = middle, in the middle, between.

21 Cf. chapter IIIB, 3h

22 Cf. chapter IV, 5i

23 Cf. the body mutilations in such a case among the Kusase (E. Haaf, Die Kusase, p. 90) and among the “Dagaba” (R.S. Rattray, The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland, p. 423).

24 Cf. chapter IV, 9, p. {136ff.}

25 This measure is perhaps intended to bring about a rebirth. Cf. also chapter I, 1.

26 Cf. the report of the school graduate, ch. I, 1.

27 Ch. I, 4 and chapter II, 3

28 The Health Centre in Sandema is a public dispensary where a few trained nurses (in 1974 there was still no doctor) have taken over the care of the sick.