CONCLUSION

1. THE ETHNOGRAPHIC DATA IN A BROADER FRAMEWORK

The main aims of the first edition of this work were to collect material on rites of passage at a certain time (1972–1974) among a specific ethnic group (the Bulsa), to examine them critically, place single observations into the right general context and present them in a form which allows for further research. However, this self-restraint in treating topics has already been broken at some points in this work to make room for attempts at interpretation or explanation immediately following the presentation of information. These include, for example, the attempt to interpret the wen-piirika {p. 193ff.} or the mental association of excision and its ritual accessories with the birth process {p. 225ff.}.

The conclusion of this study will attempt to suggest how the data obtained in the field research can be placed in a different and broader context while indicating potential avenues for future evaluative research. Here, there are two main possibilities:

1. The ethnographic data of the Bulsa rites of passage can be compared with similar data from related ethnic groups, such as the Mole-Dagbane or Gur-speaking populations, to assign them a place in the larger cultural unit.

2. The data can be examined for their function in the overall social organisation of the Bulsa. Here, acculturation phenomena would also have to be included. In the statements of the school-educated younger generation on the rites of passage and the description of their conflicts, the attitude of the pupils and school-leavers has already been indicated in other parts of this work. Still, it will be summarised here from a more general point of view {305}.

2. COMPARISON WITH OTHER ETHNIC GROUPS IN NORTHERN GHANA

The method of comparing the cultural structure of ethnic groups will undoubtedly lead to diachronic problems at some point. Moreover, remarkable similarities in the rites of passage of neighbouring groups give rise to questions of the following kind: How is this similarity explained? By common descent? By parallel but independent development that started from the same foundation? By similar environmental challenges? Or through cultural contacts? Finally, who were the people contacted?

The method indicated here would perhaps not only bring historical depth to the subject matter of this study [endnote 1] but possibly retroactively facilitate the understanding of some Bulsa rites.

In my experience, there is a vigorous exchange of ritual practices, religious attitudes, and ‘gods’ (bogluta) among the Bulsa with neighbouring societies, with the Bulsa probably belonging more to the receiving than the giving end of this relationship. There is also a great deal of change in the traditional religious sphere, which is not only caused by contacts. Changes in courtship and marriage customs in recent decades have already been mentioned. This is probably not so much due to borrowing from other ethnic groups in northern Ghana. It is instead an expression of a younger generation’s new attitude towards life, which can likewise be traced back to various influences – including that of European culture.

Examples of genuine cultural borrowings in the religious field, especially from the Kasena and Tallensi, whom the Bulsa highly respect in religious matters, can also be attested to in more recent years.

A few decades ago, the cult of a new nabiuk-bogluk {cf. p. 82} borrowed from the Kasena spread so widely that in some parts of the Bulsa country, this bogluk was to be found in {306} almost every compound. As quickly as this cult grew, it was abandoned again. When the ineffectiveness of this bogluk was realised, the sacrifices were mostly discontinued; the bogluk fell into disrepair or was even removed from the house.

More recently, the possibility of cultural influence has increased immeasurably through modern means of communication and transport. In particular, the cultural influence of the Akan people on the ethnic groups of northern Ghana is worth investigating. In this study, the small Akan facial scar seems to increasingly displace the tribal scars of the Bulsa in recent times, and male circumcision, practised in some parts of southern Ghana, is on the rise among the Bulsa; concurrently, female excision has become less popular. Some Bulsa have already attempted to offer akpeteshi (brandy made from the oil palm sap) to their dead ancestors, as is customary in southern Ghana. Akan names also occur in large numbers alongside Bulsa names, but only Bulsa names have yet been given at the segrika.

Despite great difficulties, I consider a religio-ethnological comparison of the ethnic groups within northern Ghana to be feasible and worthwhile since, for example, some rites in some groups have only a rudimentary character, and a possible interpretation can result from the studies of other groups [endnote 1a]. However, this interpretation gives information about the origin and former function of the rites rather than about their meaning in contemporary society. Here, comparisons can only be made insinuatingly: They do not belong to the actual concern of this work, and the existing literature contains too little ethnographic data on rites of passage.

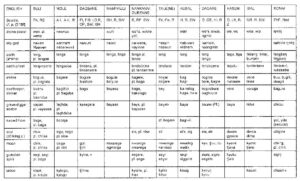

It would make sense to begin by comparing important religious terms used by some of the Gur-speaking tribes of northern Ghana. R. S. Rattray has already published a compendium of religious terminology (terms used in religious observances) [endnote 2]. Unfortunately, however, the corresponding terms in Buli are absent. Therefore, building on Rattray’s table, a similar overview will be given here {p. 312}, supplemented by information from more recent literature and which has been more closely {307} aligned to the subject matter of this study through abridgements and extensions.

Even a cursory glance at the table reveals the high degree of correspondence of the terms in the Mole-Dagbane languages [endnote 3]. Whether Rattray has included the equivalent term in the overview is questionable in some cases. Under the heading shrine, for instance, he mentions Tib-yiri for the ‘Loberu’ [endnote 4], about which he writes (p. 43) that it may mean ‘home of medicine’. This form can probably not be compared linguistically with words such as boga, bogluk, etc., whose meaning is much broader (cf. English shrine).

Linguistic phenomena that can probably be assigned to Rattray’s terms have led M. M. Delafosse [endnote 5] to far-reaching speculations about possible linguistic affinities. He starts with a study of religious terms of the Mande language (langue Mandingue) and believes that almost all the religious terms of the Mande language have equivalents in other Sudanese languages, even equatorial, eastern, and southern African languages. He remarks (p. 371):

Aussi bien les termes employés en mandingue dans le domaine religieux ont-ils presque tous des correspondants exactement similaires dans les autres idiomes soudanais et dans les langues de l’Afrique équatoriale, orientale et méridionale, ces correspondants dérivant pour la plupart de racines communes à l’ensemble des parlers négro-africains.

As a result, almost all the religious terms used in Mandinka have exactly the same correspondents in other Sudanese idioms and in the languages of equatorial, eastern, and southern Africa, most of which derive from roots common to all Negro-African languages.

Delafosse also makes linguistic comparisons for some terms. In our context, his comments on the Mande term ‘boli’, whose contents are very close to that of the Buli word ‘bogluk’, are intriguing. Whether there is a linguistic relationship cannot be decided with certainty here, but it must be noted that in bogluk [‘bɔγluk, ‘bɔ:luk] -uk is a suffix that does not belong to the root and that [g] is a velar fricative sound that can only be heard very faintly in this phonetic composition. Delafosse explains the term boli as follows (p. 379) {308}:

C’est le motif boli qui sert à désigner toute représentation matérielle d’une divinité (statue ou masque), ainsi que tout objet dans lequel une divinité passe pour s’incarner volontiers ou plus simplement dans lequel elle aime à faire sa demeure …

Les âmes des ancêtres ont leurs boli, qui sont représentés en particulier par les nombreuses statuettes funéraires répandues partout. Les divinités généralisées ont aussi les leurs, qui sont tantôt des représentations animales (crocodiles ou serpents en argile), tantôt même des animaux vivants…

The boli motif is used to designate any material representation of a divinity (statue or mask), as well as any object in which a divinity willingly incarnates or, more simply, in which it likes to make its home…

The souls of ancestors have their own boli, represented in particular by the many funerary statuettes scattered everywhere. The generalised divinities also have theirs, which are sometimes animal representations (crocodiles or clay snakes) [and] sometimes even living animals…

According to Delafosse, varieties of the word ‘boli’ are found in many African languages (p. 379):

Citons en vaï gbori, en soussou béri, en samo béne, en songaï folle, en peul et en haoussa bori, en agni buru et bunu, en dahoméen vodu … en fang du Gabon mbole, etc.

Examples include Vai gbori, Sousou béri, Samo béne, Songaï folle, Peul and Haoussa, bori, Agni buru and bunu, Dahomean vodu… in Fang du Gabon mbole, etc.

Here, Delafosse seems to have gone too far, in my opinion. The relationship between the cited terms is neither evident from their appearance nor are linguistic derivations carried out or references made to them in literature. In addition, the ethnic groups listed do not form a closer unit locally or culturally.

A linguistic comparison of the terms cited in the table on p. {312} seems more desirable than searching for possible linguistic similarities between distant ethnic groups. R.S. Rattray sees a linguistic relationship between the corresponding terms of the English words soothsayer and shrine (Buli: bogluk). He writes (p. 44):

The root of the word used to describe this person [soothsayer] is generally the same as that found in the word for shrine.

E. Haaf [endnote 6], following Rattray, holds a similar view for the Kusal. In Buli alone, such a linguistic relationship would be less noticeable (baano = soothsayer, bogluk = ‘shrine’). If Rattray and Haaf are right, g [γ] might have been dropped out of an old Buli variety for baano (cf. Kusal ba’a). Other examples of a [γ] elimination can be found in Buli. Both {309} pronunciation options (with or without γ) mostly coexist as variants [endnote 7], e.).:

bogluk: [‘bɔγluk] or [ bɔ:luk].

doglie: (‘dɔγlie] or [‘dɔ:lie]

dakogsa: [dakɔγsa] or [dakɔ:sa]

ngankpagsa: [ŋankpaγsa] or [ŋankpa:sa]

(Engl. doctor) [dɔγta] or [dɔ:ta]

Notably, a stretching of the preceding vowel occurs with the omission of the [γ]. In addition, this could perhaps explain the long vowel in (Buli) baano [ba:nɔ].

Based on the Buli vocabulary, a linguistic relationship between bogluk and bage (‘sacred horn’) also seems possible. As already indicated (cf. p. {172} endnote 24), bage can only be used for a sacred horn that may be filled with earth sacrificed to or that has a healing effect but not for a profane animal horn (nyiili, pl. nyiila). It has already been mentioned {p. 172} that the ma-bage of the Bulsa consists of a clay pot filled with earth and that one cannot find a proper explanation for the word bage here unless one assumes a (former?) meaning that goes beyond the term ‘horn’. It approaches the term bogluk in terms of meaning.

If conducted scientifically, language comparisons between religious terms could give further important information on their meaning. They cannot be continued here, although conjectures remain that in the Buli language, other terms are related to the root *bag-, such as the verb baga (to be able, to force, to have power). Moreover, linguistic comparisons contain the great danger that, after proving linguistic similarities, one also concludes that the terms’ content is identical. Borrowing a name without the corresponding meaning and applying this name to a different situation or object cannot be ruled out in practice, nor can a subsequent change in the meaning while retaining the name.

Therefore, from an ethnological point of view, a linguistic comparison should always be accompanied by a comparison of the meaning {310}. It is doubtful whether ethnographic comparisons of religions are worthwhile if there is no linguistic agreement. Is it appropriate, for example, to compare the child-kwara of the Kasena [endnote 8] with the wen-bogluta of the Bulsa? I believe this question must be answered in the affirmative because only a comparison can reveal whether similarities are based only on external appearances or whether there is an inner relationship even without the linguistic similarities of the two terms. By no means should the possibility be excluded that religious institutions of two ethnic groups have grown out of a shared basis or have been borrowed from each other without retaining the original designation.

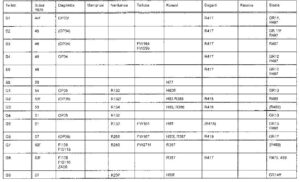

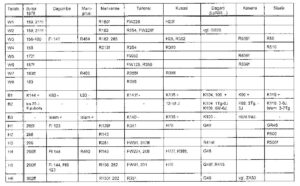

A detailed comparison of the Bulsa rites with those of the neighbouring tribes must be reserved for later work. Here, only a table {p. 313f.} will provide further references to literature and thus point out some similarities of Bulsa sub-rituals with those of other ethnic groups. The starting point for the list was the rites of the Bulsa. Substantial similarities between the rites and ideas of other groups for which there is no evidence among the Bulsa (e.g. a prenatal conversation between the personal wen with Naawen) were not included. Note that in its present form, the table can say nothing about the degree of similarity between the rites in question. It has only examined some ethnographic works for statements about sub-areas of this work and sifted and ordered some of the material for comparison.

Despite these imperfections, the following conclusions can be drawn from this table:

1. A general comparison and summary statements about the rites and customs of the ethnic groups of northern Ghana can be made only imperfectly based on the available literature testimonies. Further field research, especially on circumcision and excision rites, is necessary.

2. The material on the rites of passage seems available to a greater or lesser extent among the various groups {311}. For the Kusasi and Sisala (Isala), the more recent literature (E. Haaf; B. Grindal) provides more source material. For the Mamprussi, Dagomba and Kasena, research on rites of passage seems to be of greater urgency.

3. The leading source for comparative observations is Rattray’s two-volume work, The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland (1969).

Some difficulties arose in the table’s elaboration. Usually, it is difficult to compare a complete ritual sequence during the transition to another life status with a similar one in a neighbouring tribe without comparing partial aspects or partial rituals with each other. This difficulty raises the question of how large or small these single elements are if they are to be suitable for comparison but will not fall into the danger of atomisation. The statement ‘The Sisala, like the Bulsa, know a naming ritual associated with sacrifices and rites’ would still be mostly devoid of content since the comparison unit is too large. If one wanted to compare the knock (with the diviner’s stick or hand) that a child receives at the wen-piirika with similar blows at an initiation ceremony of Tribe X, one would have to accept the reproach of having broken down ritual processes into too small individual elements and taken them out of their context that all comparisons become suspect.

I have endeavoured to include in the comparative table only the ritual elements that still show a clear relationship to the whole and often consist of several individual acts. They have also been compiled in the table according to the corresponding elements from the same rite of passage of other ethnic groups under one heading. Actions and attitudes that arise as self-evident facts from a particular situation (sparing mother after childbirth from hard work, sacrificing to a newly created bogluk) have been omitted, as have facts that are considered familiar to northern Ghana and larger parts of Africa (e.g. ancestor veneration through sacrificial acts) {315}.

A COMPARATIVE OVERVIEW OF SOME RELIGIOUS TERMS (simplified after 1978)

In the overview of religious terms {p. 312}, names and designations without references (as far as they are not Buli terms of this work) refer to Rattray (The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland), p. 45.

COMPARISON OF RITUAL SUBSTRUCTURES

S1-G9

G10-N5

W1-H5

H7-H15

1. NOTES ON THE TABLES

1. Abbreviations of the references {313–314}

The numbers after the capital letters indicate the page numbers. In the column ‘Bulsa’, these page numbers refer to the first edition of this study.

Bracketed literature references indicate that the source contains references to the corresponding topic. However, fundamental differences may exist, the existence of the element to be compared may be too explicitly denied, or the information in the source is too imprecise to classify it here clearly. Missing information (‘empty fields’) in the table does not mean that the ritual or secular activities in question do not exist in the ethnic group concerned, but only that the information about it is missing in the literature or was inaccessible.

{315–319} The capital letters of the references in the main part of the table have the following meaning:

AI or AII = R. P. Alexandre, La Langue More, 2 vols., Dakar, 1953.

D = K. Dittmer: Die sakralen Häuptlinge der Gurunsi im Obervolta-Gebiet, Hamburg 1961.

FD = M. Fortes: The Dynamics of Clanship among the Tallensi, London, New York, Toronto, 1945.

Fk = F. Kröger and B. Baluri Saibu: First Notes on Koma Culture… Münster et al. 2010,

FW = M. Fortes: The Web of Kinship among the Tallensi, 3rd ed. London, 1967.

FN = M. Fortes: ‘Names among the Tallensi of the Gold Coast’, Afrikanistische Studien, 26 (Berlin, 1955), pp. 337–349.

FI = R. Fisch: ‘Die Dagomba’, Baessler Archiv, 3, 1912/13, pp. 132–164.

FIS = R. Fisch: ‘Dagbane-Sprachproben’, 8th Supplement to the Yearbook of the Hamburg Scientific Institutes, XXX, 1912, Hamburg, 1913.

FIW = R. Fisch: ‘Wörtersammlung Dagbane – Deutsch’, Mitteilungen des Seminars für Orientalische Sprachen, 16, 1913, 3., pp. 113–214.

G = J. Goody: The Social Organisation of the LoWiili, London, 1967.

GB = J. Goody: The Myth of the Bagre, Oxford, 1972.

GH = J. Goody: ‘Sprachproben aus zwölf Sprachen des Togohinterlandes’, Mitteilungen des Seminars für Orientalische Sprachen, 14, 1911, 3, pp. 227–239.

GR = B. Grindal: Growing up in Two Worlds, New York, Chicago et al. 1972.

H = E. Haaf: Die Kusase, Stuttgart, 1967.

HI = V. M. Hien and J. Hebert: ‘Prénoms theophores en pays dagara’. Anthropos, 63/64 (1968/69), pp. 566–71.

LK = Language Guide: Kasem Edition, Bureau of Ghana Languages, Accra (Second Edition), 1967.

LD = Language Guide: Dagbani Version, Bureau of Ghana Languages, Accra (Second Edition), 1968.

NAD = Naden, Tony: ‘Première note sur le Konni’. Journal of West African Languages XVI, 2 (1986), 76–112.

OP = Chr. Oppong: Growing up in Dagbon, Accra-Tema, 1973.

R = R.S. Rattray: The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland, 2 vols.

RP = E.L. Rapp: Die Gurenne-Sprache in Nordghana, Leipzig, 1966.

SW = M. Swadesh et al.: ‘A Preliminary Glottochronology of Gur Languages’, Journal of West African Languages, 3,2 (1966), pp. 27–65.

Z = J. Zwernemann: Die Erde in Vorstellungswelt und Kultpraktiken der sudanischen Völker, Berlin, 1968 (reprint).

ZN = J. Zwernemann: ‘Personennamen der Kasena’, Africa and Overseas, 47 (1963), pp. 133–142.

ZA = A. Zajaczkowski: ‘Dagomba, Kasena-Nankani and Kusasi of northern Ghana’, Africana Bulletin, 6 (1967), pp. 43–56.

2. The ritual elements (left column)

PREGNANCY (S)

S 1 A woman’s first pregnancy is kept secret during the first months and must not be mentioned, especially to the pregnant woman.

S 2 By ‘pouring water’, the pregnancy is made known, and prohibitions are lifted {317}.

S 3 The pregnant woman is given a special (waist) cord at the ‘announcement’.

S 4 A woman from the husband’s line (often the husband’s sister) plays a particular role in the ‘announcement’.

S 5 After the ‘announcement’, the pregnant woman may be insulted or mocked (a kind of joking relationship?)

S 6 No payments shall be made to the parental home of the pregnant woman during pregnancy.

BIRTH (G)

G 1 A difficult birth or death of the child are due to the pregnant woman’s fault. As a remedy, she has to confess and sacrifice to the ancestors.

G 2 The placenta is buried in a ceramic pot (or two pots or pot halves) in the waste heap.

G 3 The dropped umbilical cord is walled in the inner wall of the ancestor’s room (often in a nutshell).

G 4 The newborn child is called a stranger or non-human being in the first days of life (cf. N 4).

G 5 Outdooring of the child, the mother, or both is done after three (boy) or four (girl) days.

G 6 During the breastfeeding period (2–3 years), the mother should not have sexual intercourse because a new birth at this time is undesirable.

G 7 Twins are rejected, require special treatment, or both.

G 8 Certain physical peculiarities of the child (e.g. birth with teeth already present, hair on the head) and deformities suggest the birth of an evil being (Buli: kikiruk) and require special treatment (the children were often killed in the past).

G 9 Infants can easily be reborn to the same mother.

G 10 Infant mutilations are performed in cases of frequent miscarriages and infant mortality.

G 11 After a (first) miscarriage or after the early death of an infant, the parents’ hair is shorn.

G 12 Dead infants (mostly premature or stillborn) are buried in the rubbish heap {318}.

G 13 Dead infants are buried along a footpath.

G 14 Dead infants are buried behind the compound or against the compound’s outer wall.

G 15 If a pregnant woman dies, her embryo is removed from her womb.

G 16 If a pregnant woman dies, she does not receive a proper funeral service (she is often buried in the bush).

NAMING AND NAMES (N)

N 1 The reason for the ritual called segrika among the Bulsa is the child’s educational difficulty, restlessness, or bodily or mental illness.

N 2 The child is offered to a guardian spirit (root *seg or similar) or may be named after it.

N 3 The diviner determines the guardian spirit or the reincarnated ancestor.

N 4 Until the child is officially named, it has a provisional name: Sana, Saando, Saanpaga, Sanpan, Asanpan, Ajampan, Anpan and the like.

N 5 After previous miscarriages, the next child is given the name ‘slave’ or is named after a ‘slave tribe’ (e.g. Kantussi, Mossi, Haussa, etc.).

WIN, YIN… (W)

W 1 The (personal) wen is already present before birth.

W 2 The wen (a supernatural power associated with a particular person) descends from heaven.

W 3 The wen receives a shrine made of earth (‘altar’).

W 4 The ‘earth altar’ receives a stone.

W 5 Wen-shrines of the male ancestors stand in front of the compound.

W 6 Ancestresses receive a shrine and sacrifices, too.

W 7 Female ancestral wen-shrines may be transferred from a compound where the ancestress had lived and died as a wife to the compound of a specific descendant of her line (Bulsa: ma-bage rites).

W 8 The performer of specific wen rites must not speak the whole way {319}.

EXCISIONS AND CIRCUMCISIONS

B1 Female excision is practised (+) or not (-)

B2 Age of the excised girls

B3 Male circumcision is practised (+) or not (-)

COURTSHIP AND MARRIAGE (H)

H 1 The suitor should not enter his future wife’s paternal compound if they are plaiting a mat or making shea butter.

H 2 If a mat is being plaited or shea butter is being made at the bride’s compound during home visits, this is considered a bad sign.

H 3 An intermediary is called in for financial arrangements. He usually comes from the groom’s section but has kinship ties to the bride’s section.

H 4 Marriage can be arranged by the parents (even if the children are still very young).

H 5 ‘Abduction’ of the bride (elopement and marriage by capture).

H 6 Brothers of the bride visit the groom’s house and receive a dog (possibly another animal).

H 7 The bride’s brothers can make uninhibited demands in the groom’s house (behaviour is institutionalised).

H 8 The husband does field work for his parents-in-law after the wedding (partly annually).

H 9 After adultery, the guilty woman must confess her guilt and her lover’s name.

H 10 Adultery: A chicken is killed during the rites of reconciliation.

H 11 Cicisbeism: The (very old) husband allows his wife to have sexual intercourse with a lover. The children of this union belong to the lawful husband.

H 12 ‘Platonic’ friendship of a married woman with another man, mostly from the husband’s lineage (Buli: pok-nong relationship).

H 13 A divorce is usually completed without a formal divorce ceremony. The wife is sent home or leaves her husband at her own wish.

H 14 A widow shall remarry into the lineage of her deceased husband.

H 15 After the death and funeral of his father {320}, a son may marry one of his father’s wives if she is not his birth mother.

3. FUNCTION OF THE RITES OF PASSAGE

As already indicated above {p. 304f.}, the Bulsa rites can not only be compared with similar rites of neighbouring groups and placed in a larger religio-ethnological framework but also examined for their functional value in the social order of the Bulsa. Here again, several ways present themselves.

Thus, interdependence and correlations between the rites discussed here and other elements of the Bulsa culture as a whole and data by other authors might be topics worth investigating.

For example, Judith Brown [endnote 9] investigated why female initiation rites are practised in some societies but not others. Based on Murdok’s ‘World Ethnographic Sample’, she examines 75 societies from all parts of the world for the presence of female initiation rites, which she defines as follows:

…it [a female initiation rite] consists of one or more prescribed ceremonial events, mandatory for all girls of a given society, and celebrated between their eighth and twentieth years. The rite may be a cultural elaboration of menarche but should not include betrothal or marriage customs.

According to this definition, the excision rites of the Bulsa would also have to be counted among the ‘female initiation rites’, even if the condition ‘mandatory for all girls’ no longer fully applies in recent times. J. Brown comes to the following conclusions in her study (p. 849 f.):

First, female initiation rites occur in societies where the young girl does not leave the domestic unit of her parents after marriage. As she spends her adult life among the same {321} people and in the same setting as her childhood, the rite represents a special measure taken to proclaim her changed status when she reaches adulthood.

Second, those few female initiation rites which subject the initiate to extreme pain are observed in those societies in which conditions in infancy and childhood result in a conflict of sex identity …

Third, female initiation rites are found in those societies in which women make a notable contribution to subsistence activities. Because of her future importance to the life of the society, the young girl is given special assurance of her competence through the rite.

The first conclusion does not apply to the Bulsa in any way, as they marry according to the principle of virilocality.

The prerequisites for J. Brown’s second assertion are also given for the Bulsa. In polygynous Bulsa society, a little girl grows up primarily close to her mother; she has her sleeping place on her mother’s mat and will identify with her, emulate her and envy her status [endnote 10]. After some time, however, drastic changes occur when the little girl experiences the power and influence of her father, of the yeri-nyono, or both. J. Brown writes about these changes (p. 843):

Thus, we see that when the young girl has experienced an exclusive mother–child sleeping arrangement, which fosters identification with the male role, conditions for identification are confusing. It is to these circumstances that the concept of ‘conflict of sex identity’ applies. And it is in societies characterised by such child-rearing conditions that we would predict female initiation rites that inflict extreme pain.

If one relates these statements to the Bulsa, it remains suspect whether a little Bulsa girl identifies with the male role to such an extent that a ‘conflict of sex identity’ arises. The girl’s close contact with her mother remains throughout childhood, while the boy falls increasingly under his father’s {322} influence. The daughter learns from her mother the skills she will later have to master as a woman. Conflicts of gender identity today probably occur the most with shepherd girls, who must learn a role that used to be reserved almost exclusively for boys (Cattle-herding is part of the man’s job, and the assessment of personality according to wrestling skills is also more characteristic of man’s approach to life). However, the herding activities of girls cannot be associated with the excision rites: only since many boys started attending school have girls entered the herding group in larger numbers.

J. Brown’s third conclusion, wherein female initiation rites are described as typical for societies where women contribute substantially to the family’s livelihood, can only be valid for the Bulsa when including substantial restrictions. Indeed, it is questionable how broadly the term ‘notable contribution’ is to be understood. That most Bulsa women contribute their share to the upkeep of their children, for example, and thereby relieve their husband or the head of the household, is beyond question. The married woman can work a piece of land allocated to her by the yeri-nyono, for example, and earn a welcome extra income through pottery or market trading. The man (yeri-nyono) is responsible for organising livestock breeding and field cultivation. Although women must take on specific tasks, the main burden of working in the fields and caring for the family is not solely on women.

In summary, J. Brown’s results do not entirely apply to the Bulsa society. If I understood her correctly, she did not want to state laws that apply without exception but only to discover certain tendencies by analysing ethnographic data of a sample of 75 societies. As her tables show, there are many ‘patrilocal’ (virilocal) societies (e.g. the Mossi) where female initiation rites are practised.

According to R.S. Rattray, excisions are carried out during {323} or shortly before puberty among the Kasena, Nankanse (Gurensi) and some Mamprussi-influenced Kusasi [endnote 11]. While the Dagaba (Dagarti), Wala, Isala (Sisala), Vagala and Fera (Awuna) have their girls circumcised shortly after birth, and the Lober (Lobi) practice female excision on 5–6-year-old girls (Rattray, p. 439), the Namnam, Tallensi, Dagomba and Mamprussi do not know female circumcision (Rattray, p. 167). In all the ethnic groups mentioned, however, as far as I know, there should be a ‘conflict of sex identity’ in the sense of J. Brown: female infants live their lives in a polygynous extended family in which the mother takes care of her daughter almost exclusively in the first years of her life; later, the daughter feels that a man (e.g. a classificatory father) is the dominant personality of the entire household.

In the following, I will compare Bulsa rituals or parts of them with each other to find something about their meaning and value in the overall social organisation of Bulsa society.

I concur with A.W. Radcliffe-Brown [endnote 12] when he writes (about the Andaman Islands):

The explanation of each single custom is provided by showing the nature of its relation to the other Andamanese customs and their general system of ideas and sentiments.

Accordingly, our investigation must begin again with the Bulsa rites of passage. Since their function is to be examined in general terms, the first question can be: What do all or many Bulsa rites of passage have in common? In addition to the criteria, among all rites of passage, such as (according to van Gennep) séparation (segregation, separation), marge (transition, intermediate stage) and agrégation (reception, reclassification) [endnote 13], it is striking that also other {324} ritual elements also appear repeatedly in Bulsa ones. Again, I concur with A. W. Radcliffe-Brown when he makes the following assumptions:

The assumption is made that when the same or a similar custom is practised on different occasions, it has the same or similar meaning (p. 235).

Ritual Elements

The following ritual elements occur in several Bulsa rites of passage [endnote 14]:

1. Various types of taboos (kisika)

a) Sight taboos during pregnancy, birth, wen-piirika, and excision

b) Speech taboos during excision and ma-bage rites (cf. prohibition to speak about a particular subject or condition during a wen-piirika and pregnancy)

c) Food taboos during pregnancy, birth, umbilical circumcision, excision

d) Behavioural taboos during pregnancy, birth, segrika, wen-piirika and others

e) Prohibition to wash oneself before an activity: before divination at wen rites

f) The circumciser of umbilical incisions must not eat or drink anything before the operation and must not rinse his mouth

2. Prescribed colours with a symbolic character

a) A black or dark (sobluk) colour is prescribed for objects in the following rituals:

Ashes at pobsika rites (exception: excision pobsika),

several types of medicine (mostly made from dark ash and shea butter),

a calabash at the poi-nyatika,

blacksmith’s calabash helmet (shepherd boys have an uncoloured calabash helmet),

chickens for ordinary sacrifices

Waist strings for ‘everyday’ use (supposedly, they have the same meaning as the black and purple strings).

b) The following things should be of a white or light (peeluk) colour:

pobsika ash after excision

Ash placed in a heap on the ground at all four corners of the millet field before harvesting the late millet

Ashes placed on the head of a deceased infant {325} if the mother has previously had several children die at birth or shortly after birth

Excision fibres as a replacement for clothing

The millet stalk (ngabiik kinkari) that girls receive after excision (it must not have dark burn marks)

a chicken as payment to the circumciser (if the girl has already had sexual intercourse)

a small chicken at the wen-piirika

sacrificial animals in exceptional cases (applies especially to chickens), such as for juik-bogluta (juik, pl. juisa; Engl. mongoose) or certain ngandoksa (all ngandoksa demand a specific colour of the desired sacrificial animal)

white chickens are killed after preceding disreputable offences (e.g., kabong)

waist strings of a woman if she has had several miscarriages, triangular cloths (golung, pl. golunta) in which boys are buried if their mother has already given birth to another child after them (adult men may also wear striped triangular cloths to the grave)

c) Prescription for a red or red-brown colour (moanung):

For certain body paintings (cf. p. 136 f.), a red and black waist cord is put on the pregnant woman after the poi-nyatika, while a purple and black waist cord is worn if no other colour is prescribed [note 15].

A sleeping mat must always contain some lilac (moanung) coloured stalks.

d) Ngmengmeruk (pl. ngmengmeruta, meaning ‘multi-coloured, colourful’) is sometimes mentioned as a colour. However, it does not seem to play a role in ritual life. Multi-coloured chickens can usually be sacrificed in place of dark chickens.

e) Leander mentioned lilac or violet (nalik, peeuk) as another colour of the Bulsa. However, it does not play a role in rituals as an independent colour and is unknown to many other informants. Most Bulsa use the term ‘moaning’ for a purple hue.

3. Prescribed numbers and quantities (number symbolism):

The connection of the number three with the male and four with the female gender occurs so frequently among the sa that only a small selection can be given here (a–f) {326}:

a) Pregnancy and birth: A fourfold (?) waist cord is put on the pregnant woman.

The male or female child is carried out on the 3rd or 4th day, respectively.

b) Pobsika: blowing ash three or four times (not confirmed by observation).

c) Wen rites:

Three or four strokes of the soothsayer’s stick at wen-piirika.

Three or four days after the wen-piirika is the first offering to the wen by the new owner.

Three or four kauri snails as ornamentation on a bogluk.

A potter demands 40 pesewas for a puuk pot. The buyer puts the money in the pot three times; the fourth time, the potter takes it.

d) Scars: Usually three or four scars for boys and girls, respectively (tribal and bia-kaasung scars).

e) Excision:

Circling the gaasika-calabash around the body four times and spitting out the gaasika-millet water four times.

Isolating the girl until the fourth day after excision.

Only allowing the water to carry away the millet stalk on the fourth attempt {cf. p. 225}.

f) Courting and wedding:

Four single pesewa coins as part of the nansiung-lika payments.

Sexual intercourse of the bride and groom is only allowed on the fourth day after the bride has been brought home.

4. Pobsika (blowing ash)

a) After birth.

b) For certain children at a new moon {see p. …}.

c) Before the wen-piirika.

d) After excision.

e) Craftsmen are not allowed to continue working after sunset. If they do wish to do so, they must blow ashes (pobsi) with the sun. Otherwise, they may go blind.

f) In Gbedema, the head of the compound had to blow ashes (pobsi) with a bitch that had just given birth to cubs before the sacrifice at a juik shrine was performed. The connection with the juik sacrifice probably results from the dog being an enemy of the juik animal (mongoose). For the pobsika, the dog was closed off in a room. The officiant covered his eyes and blew ash through a small gap into the room. The dog’s eyes were open. Failure to perform the pobsika would have resulted in the dog’s death, not in the compound owner’s death, who was protected by medicine.

g) Before cultivating and harvesting specific crops (I. Heermann, 1981: 76; no further confirmation).

5. Gaasika, a ritual meal

a) After a miscarriage

b) After an excision

c) After a snake bite

d) Only among the North Bulsa: after returning home from a long journey {327}

e) After the construction of a new house

f) After killing a large bush animal (e.g. during hunting)

g) After the killing of a human being (e.g. in war)

6. Ponika, the shaving of the head hair

a) After the first miscarriage

b) After the death of the spouse

c) After excision

7. Pouring water over a person

a) At the poi-nyatika

b) After birth (mother and child)

c) At a segrika ritual

d) After excision

f) At the bath of the bride and groom

g) After a divorced wife returns to her husband’s compound

h) For dying people (probably more to relieve pain)

8. Piirika (see fn 1981, 41b)

a) Wen-piirika

b) Before a divinatory session with a different meaning: two sticks touching the divinatory bag absorb all the dirt (daung) of the preceding session [endnote 14a]

Ad 1: Taboos

The observance of taboos detach the affected persons from their everyday habits and social environment to protect them from possible dangers, which may emanate from supernatural powers, but sometimes these dangers may have a quite natural origin by preventing the ingestion of an inappropriate food.

Another social – and perhaps even economic – significance can be attributed to taboos. As already described, rites accompany a person’s transition to another status. A woman, through her first pregnancy and the birth of her first child, enters a higher social status, namely that of a mother. This new position involves several social and economic obligations [endnote 15a]. Higher payments must be made if the prescribed gifts to the woman’s parents have not yet been paid in full before the first birth. During pregnancy, there could be uncertainty about the amount of the payments. The taboo regulations prohibit all payments and gifts here, thus preventing possible conflicts.

Ad 2: Colour symbolism [endnote 15b]

Undoubtedly, most colours in Bulsa ritual events have symbolic values. However, my informants could not answer questions about a {328} valid interpretation for all manifestations, or their simplifying generalisations (white = joy and happiness; black = disaster) do not stand up to scrutiny in every respect. Accordingly, colours must be understood as value-ambivalent.

For example, E. Haaf (1967) [endnote 15c] has established for the Kusasi that the black colour can mean both wealth and disaster, the red colour effort (p. 144) or, by analogy with fire, pain and illness (p. 151). According to Haaf, white is a symbol of joy for the Kusasi. Similar interpretations have been given to me by Bulsa informants for particular explanations of prescribed colours, although I have never encountered the interpretation of the black colour meaning wealth. When interpreting the objects of a diviner’s bag (baan-yui), a scrap of red cloth was explained by symbolising the red in the eye and pointing to coming anger and wrath.

By no means can the colour white (peeluk) be consistently interpreted as a symbol of positive emotions or attributes like joy, purity, openness, or sincerity. However, semantically, this explanation is still the most accurate – peeluk is often translated as ‘joyful, sincere, honest, or clear’ – as can be seen from the following examples:

nyiam peeluk = clear water

sunum peeluk = kindness (literally ‘bright mind’)

cf. peenti (v.) = reveal, explain, make clear, become bright

po peenti = to be satisfied

po peentika = happiness

However, as the above examples from ritual life with white or light colours show, extraordinary or even particularly reprehensible things (sexual intercourse before excision; kabong) are often associated with white. A general interpretation of the colour symbols among the Bulsa is complicated because different colours may be prescribed for similar situations. After adultery, the adulterers must kill a black chicken {cf. p. 285f.}. However, if a man has married the wife of a member of the same clan section, this offence (kabong) can only be atoned for {329} by sacrifices of white animals. It is possible that white, and, thus, innocent or clean animals, are believed to absorb the guilt of the human person easier than black ones.

Sacrifices of dark chickens are presented as the customary sacrificial gifts, but perhaps only because among the Bulsa, most chickens are dark. However, people in a vulnerable state, such as girls after their excision or parents after the death of their first child, are not allowed to eat black things, and ‘black’ here is already no longer a pure colour value (e.g. all goats and turi beans are considered ‘black’), but is representative of the food that could bring harm to the person concerned.

The question of colour symbolism among the Bulsa remains unclarified in this work; the topic warrants more detailed future investigation.

Ad 3: Number symbolism (including male–female, right–left, high–low)

The assignment of the triad to the male gender and the tetrad to the female gender is not only widespread in West Africa [endnote 16], but there is also no lack of speculation and attempts at interpretation [endnote 17] as to why, in large parts of the world and at various times, people have assigned odd numbers (often 3) to the male principle and even numbers (often 4) to the female principle.

The Bulsa could not explain such an assignment to me. E. Haaf (1967) [endnote 18] obtained the following information from the Kusasi:

WIDNAM has given each person special guardian spirits, KlKYIRIG, Pl. KIKYIRIS. Originally, he considered three of these beings sufficient for everyone. One KIKYIRIS was destined to bring life (to accompany the WIN to earth), one to protect life, and the third to take life. However, the women were not satisfied with this and asked for another guardian spirit, referring to their additional task during pregnancy and birth. WIDNAM agreed, and so the men received three, the women four such KIKYRIS. This is why the Kusase generally assign the number three to the man and four to the woman [endnote 18a].

The kikyiris mentioned above likely correspond to the kikerisa (sing. kikerik) of the Bulsa [endnote 19], not the kikita (sing. kikiruk), which usually {330} have a human form (cf. p. 56 ff.). According to my inquiries (before 1974), only kikerisa can assume certain protective functions for people, but these extend to a whole compound rather than a single person. Haaf’s explanations for the Kusasi thus cannot apply to the Bulsa [endnote 19a].

I could not find clear evidence for the female or male principles’ assignments to the terms left and right among the Bulsa. Women are always buried lying on their left sides with their faces pointing west, while men are placed in the grave so that they face east [endnote 20]. However, the orientation towards the rising and setting sun probably plays a role in this burial practice.

I know of several examples of the masculine and feminine principles associated with ‘large’ and ‘small’ concepts. Here, perhaps unexpectedly, the female is associated with the large, and the male is associated with the small. A large ash heap – such as one might find in front of a chief’s compound – is called tampoi nuebi (nuebi = female), and a small ash heap is called tampoi diok (diok male). Among the wind instruments made from buffalo horns, up to six of which are blown at festivities (Kröger 2001: 732), the largest, lower-sounding horn is called namun-nuebi (female horn), and a smaller, higher-sounding horn, namun-diak (male horn). This aligns with the fact that a low human voice, more common among men, is called loeli-nuebi (female voice), and a high voice (my informant speaks of ‘child soprano’) is called loeli-diak (male voice). The number of examples could be increased considerably.

Unfortunately, I could only hear contradictory statements about whether, in a nipok-tiim, the smaller or the larger medicine pot is designated as male.

Ad 4 and 5: Pobsika and Gaasika

Here, I aim to describe pobsika and gaasika as typical rites of reintegration (agrégation) into profane life. While pobsika lifts an existing visual taboo, the gaasika rite allows the {331} consumption of things whose enjoyment was previously forbidden. The lifting of a taboo through a shared meal [endnote 20a] does not seem to exist only among the Bulsa; van Gennep [endnote 21] writes in connection with the discussion of rites applied to the building of a new house:

Aux rites de levée de tabou… succédent des rites d’agrégation: libations… partage du pain, du sel, d’une boisson, repas en commun…

The rites of lifting taboos are followed by rites of aggregation: libations… sharing bread, salt, a drink, a communal meal…

Ad 6: Ponika

The ritual shaving of the head hair (ponika) causes difficulties in classifying it per van Gennep’s scheme. At first glance, together with body painting (e.g. when a person is injured and at memorial services for the dead) and unusual clothing (e.g. excision fibres, ‘red cap’), it seems to set the endangered person apart from others via their outward appearance. Van Gennep himself writes about cutting off the hair: ‘couper les cheveux, c’est séparer du monde antérieur’ (p. 238).

That the Bulsa shave their hair only at the end of a series of ritual actions seems to speak against these explanations. When questioned, most Bulsa could not give me a plausible explanation for the ponika rite. Still, it was brought to my attention that all Bulsa chiefs and earth priests (teng-nyam) must shave their heads regularly, while some medicine men (tiim-nyam) are never allowed to cut their head hair [endnote 21b].

E. Haaf [endnote 22] contains an explanatory note:

Eine Behandlung der Pocken kennen die Kusase nicht. Man ist nur darauf bedacht, dem Erkrankten die Haare zu scheren. Man nimmt nämlich allgemein an, dass die Krankheit, wie auch die Gifte, in die Haare steigt; würden diese nicht entfernt und sorgfältig vergraben, so gehe diese Erkrankung auf andere Leute über. Wird das Haarscheren versäumt, kann dem Kranken, falls er stirbt, kein normales Begräbnis gewährt werden.

The Kusase do not know any treatment for smallpox. They are only concerned to shave the hair of the sick person in time. It is generally assumed that the disease, like the poisons, gets into the hair; if it is not removed and carefully buried, the disease is passed on to other people. If the hair is not shorn, the sick person cannot be given a normal burial if he dies.

{332} Among the Bulsa, I have not received such a clear explanation of the ponika, but there are indications that similar ideas may exist among them. Aguutalie said in her excision report about her hair being cut at the ponika:

Ka ngarika zuesa le la.

It [the head hair] is excision hair.

When I asked her what she meant by that, she answered that the hair had grown during and after excision and thus needed to be cut off. This response was all I could get from her.

In retrospect, according to these explanations and if one understands the period of a life crisis and the rites associated with it as the preceding time, van Gennep’s statement that a ritual haircut is supposed to detach a person from what precedes can still prove relevant for the ponika of the Bulsa.

Ad 7: Pouring over with Water

The ritual act of pouring water over a person usually occurs in the middle of a series of ritual actions. It may be objectionable that washing has a hygienic rather than a ritual character; the baths of the bride and groom and the baths of the mother and her child after birth are regarded worldwide as hygienic necessities. As already indicated, however, the profane function of the bride’s and groom’s baths is supplemented by the ritual significance of removing existing sexual guilt. Nevertheless, there may be another ritual function: Just as the daily bath of the Bulsa is meant to cleanse and cool down the heated body, the ritual bath also encompasses this intention figuratively. To make this assumption credible, the Bulsa people must see a person in a life crisis as someone in a ‘heated’ state who is ‘cooled down’ by the rites of passage and thus returned to normal. This proof is not particularly difficult for the Bulsa. Still, the two Buli words for cold (yogsuk) and hot (tuilik; tuling) should first be checked for their linguistic meaning [endnote 23] {333}.

1. The Buli word yogsuk is used for the English words cold and cool. Word derivatives of the root *yog include [endnote 23a]:

yogsuk, pl. yogsa (adj.): cool, cold, green (vegetation), fresh, wet, damp, timid

yog(i) (v.), yok: to be cool, to become cool, to be healthy, to moisten (e.g. material for braiding and weaving), to weave

yogsa (v.): to be cool, to be fresh

yogli (v.): to refresh oneself (by drinking or bathing)

yogsum, yogsim, pl. yogsita: coolness, dampness, shadow, fear

yog, pl. yogta: night

yog-nyieng, pl. yog-nyiengsa: sick person (nyieng = sick)

chali yogsum: to be afraid (lit.: to run from the shadows)

kali nying yogsa: to rest; to be happy and content (kali = to sit; nying= body)

suiyogni: balance, thoughtfulness (literally: cool mind)

nying yogsa: health

ku(m) yogsuk: ‘fresh death’ (a death that has just occurred).

‘Ba sue a yogsa ale chaab’: ‘They get along (their hearts are cold among one another)’.

‘Wa yog kama’: ‘He is cold; He is dead.’

The brief compilation demonstrates that the linguistic root *yog, whose basic meaning is perhaps ‘cool’, tends strongly towards the secondary meanings of damp, wet and dark (cf. night, shadow). This is {334} unsurprising, for in the hot Bulsa country, dampness (e.g. rain, bath by pouring water), shade and night bring the body the longed-for cooling. Thus, ‘cool’ and ‘wet’ can easily be associated with the same word (yogsuk).

2. For the word tuilik or tuling (hot), the following derivations are listed as examples:

tuilim, pl. tuilita (n.): heat, desire, envy

tuila (v.): to be hot, to be heated up

tualengi (v.): to heat up

nying-tuila (n.): disease (lit. ‘heat of the body’)

tuum [tyym]: disease, a difficult thing

3. Possibly, the following terms share an etymological relationship:

tuok, pl. tuosa (adj.): difficult, bitter,

tua, toa (v.): to be difficult, to be bitter

tuaring (v.?): to be angry, to rebuke

tuini, pl. tuima (n.): work

Even if one does not take into account the dubious last derivations, it can be seen that with the root *tuil, besides the idea of heat, an imbalance of the body or soul can also be expressed (desire, envy, illness) and that the associations of this linguistic root *tuil are more negative than those of the root *yog.

In the following, I attempt to relate the terms ‘cool’ (yogsuk) and ‘hot’ (tuilik) to rites of passage. Concurrently, I demonstrate that, in the rites of passage of the Bulsa, the person is to be led from a ‘heated’ to a ‘cooled’ state.

At the wen-piirika in the house of Leander Amoak’s compound, the diviner and his assistant said a prayer of about 320 words (text: {p. 150}), expressing five times the wish that the child’s body should become cool (…ate wa nyinka yok ngololo); the heat of the body was mentioned three times. The speeches clearly show that the child’s wen had sent the heat and was now prompted by ritual acts to make the child’s body cool again. Leander {335} told me that by ‘heat’, diseases of Akapami were meant, but Akapami’s was physically perfectly healthy during the sacrifice, even if his body was still ‘hot’. The preceding illnesses and educational difficulties were only expressions of his ‘hot body’, which was to be transformed into a ‘cool’ state with the help of his wen.

In addition, the pobsika rites can be associated with the concept of cooling: Every ash [endnote 24], for example, is made through a cooling process. Likewise, the people who perform the pobsika rites also want to end their ‘hot’ and endangered state.

J. Goody [endnote 25] has observed this connection among the LoWiili:

Finally, it is said that in any [fight], the joking partners of either combatant could bring the fight to a standstill by ‘throwing ashes’ (loba tampelo), a phrase, often used metaphorically, which invokes the essential features of the relationship, the power to make ‘hot things cold’, to restore equilibrium in situations where the group or individual has lost control.

Evidence supports that similar perceptions exist among other ethnic groups in northern Ghana [endnote 25a].

The ‘hot state’ is not always seen as something that needs to be quickly transformed into a cool state. For example, E. Mendonsa (1975: 66) reports the making of a nadima bracelet, which, among the Sisaala, embodies the soul of the wearer. The blacksmith cannot wash his face with water before starting work because this would have deprived him of his hot ritual state. The hot bracelet must also not be transferred to a cool state after it has been made: ‘He [the blacksmith] does not dip it in water to cool it off, as is normally done with other metal objects he makes [endnote 25b]’.

Rattray’s assistant, Victor Aboya, reports that among the Nankanse (Gurensi), a husband longing for his wife’s first pregnancy makes sacrifices and promises to the ancestors [endnote 26].

He does all this until he arrive[s] at the true position (zia), and his body become[s] cool … Others…cool themselves properly (are patient), and the male seeks soothsayers without ceasing…

The unbalanced, dissatisfied state of the husband is seen as ‘hot’; the desired pregnancy of the wife brings back his ‘coolness’. Later (p. 353), Rattray describes a tim bagere (Buli: tiim-bogluk) of the Tallensi, which exists above all to prevent wars. At the sacrifice, the following words are spoken {336}:

My father, call your father; let women and children sleep; they wish to shoot arrows; fire wants to burn the land, but I wish it to be cool.

Rattray’s informant reports about the roots of the shea butter tree in a medicine pot (p. 353): ‘…when you eat shea butter, your heart will become cool’. Again, the ‘hot’ state can be associated with mental restlessness and aggressiveness.

According to E. Haaf, the Kusasi seem to hold similar ideas about the ‘hot’ body, which, for example, is associated with the onset of pregnancy in women. E. Haaf states [endnote 27]:

There is an idea that every conception causes ‘heat’ in the body, especially in the vagina. This heat would, in the case of a pregnancy that followed too quickly, poison the milk that the last-born child still needed.

A particular medicine used by the Kusasi to anaesthetise novice diviners is called Puug Buur. E. Haaf explains this name as meaning ‘to cool the body in the sense of quenching pain’ [endnote 28].

It has been stated here that, among some closer and more distant neighbouring tribes of the Bulsa, the ‘hot’ body can be associated with restlessness and imbalance, with an exceptional state (pregnancy), or with pain and illness. All these statements from different ethnic groups apply to the Bulsa in general. Life crises are often associated with a ‘hot’ state and certain rites of passage are supposed to bring the body back to a ‘cool’ state.

Concerning the transfer of the human being into a ‘cool’ state, I can adopt J. Goody’s explanation for the LoWiili: that the equilibrium is to be restored in situations in which the group or the individual {337} has lost control [endnote 29]. However, the question remains to what extent the ‘hot state’ disturbs social equilibrium. A review of the depicted Bulsa rites shows that the exceptional condition (the ‘hot’ state) of man can mainly express itself in two main ways:

1. Negative influence on health

2. Susceptibility to conflict

Here, I focus on the second effect. High susceptibility to conflict and difficulties in resolving the conflicts often indicate the beginning of a ‘hot’ state in a person. I recall the conflicts of children with their parents before the segrika and wen-piirika, as well as, for example, the conflicts that Leander’s first wife had with the children of the other wives, necessitating a reshaping of her wen-bogluk.

Thus, the rites and customs have their function, in the sense of M. Gluckman [endnote 30], of overcoming social conflicts by emphasising and recognising conflict situations. In the Bulsa view, it is more a matter of conflict resolution through supernatural forces (e.g. wena, tanggbana, guardian spirits) than through a conscious social arrangement. However, the rites also contain elements in their procedure that, from a purely profane point of view, may serve as genuine steps towards overcoming social conflicts. Some of them are listed here:

1. Awareness of the conflict situation and of the actual or potential adversaries as well as unconscious aggressive feelings are raised to the level of consciousness in the rites by marking the objects of aggression. For example, after the excision, the girl must blow ashes with her parents (who forced her to undergo this ritual) and subsequent younger siblings. Through this, the individual is more likely to succeed in processing aggressive feelings and regard them as something natural (‘It is always handled this way in such situations’).

2. Complete or selective isolation

At the peak of the life crisis, e.g. immediately after birth and excision, the affected person is often temporarily isolated from the people who caused the extraordinary condition {338}. During birth and excision, men are kept at a distance since they may have caused the painful operation or demanded it from the woman and can thus quickly become the target of female aggression.

Accordingly, in some parts of Bulsa country, excised girls spend a few days almost completely isolated in a dok of the compound after the procedure. Women giving birth or being excised are also only attended to by women who have already undergone the same procedure and thus cannot become an object of envy. Taboos (especially sight and speech taboos) also keep the person in a life crisis distanced from potential sources of conflict for a short time.

3. Identifying the commonalities of the persons engaged in conflicts

A suitable means of expressing and emphasising the commonalities between conflict-prone people is the joint sacrifice to their common ancestors or other ‘house gods’. If the awareness of common ancestry already has a mitigating effect on minor disputes in everyday life (‘If he weren’t my brother, I wouldn’t put up with this’), this awareness is further strengthened by shared ritual acts. The sacrificial meal, which the sacrificial community takes together with the ancestors, constantly displays this we-consciousness. The mutual exclusivity of serious conflict and a shared ritual meal is clearly demonstrated by the teng ordeal, wherein all community (e.g. the household community, lineage) members eat the soil of a particular shrine (teng, tanggbain or miia-bage). One who has disturbed the community’s life, such as by using witchcraft, dies after this communal meal {p. 172}.

Although ordinary ancestral sacrifices do not have this character of an ordeal, persons among whom serious conflict exists dislike sacrificing together (cf. p. 170); a ceremonial greeting and a shared sacrifice are always regarded as a first step towards total reconciliation.

4. Role reversal and deviant role behaviour

M. Gluckman, in Custom and Conflict in Africa {339} – and especially in the chapter ‘The Licence of Ritual’ – describes such rites, which, in their actions, turn otherwise ordinary social roles into their opposite: Men play women’s roles, the ruler takes on the role of the servant, and where reverence and respect are otherwise demanded, the rites reveal disrespect and rebellion. M. Gluckman writes about these rites:

These rites of reversal obviously include a protest against the established order. Yet they are intended to reserve and even to strengthen the established order … (p. 109)

Gluckman’s theses are not as clearly exemplified among the Bulsa as the author describes them for societies in south and southeast Africa (Zulu, Tembu, Barotse, etc.). Still, a gender role reversal can be demonstrated at funeral ceremonies. A woman dressed in the men’s leather apron or smock can personify the male deceased on a ritual level and, for example, lead a war dance group (Inf. R. Schott). Whether a chief or earth priest (teng-nyono) can ritually assume the role of a servant on certain occasions (e.g. at the investiture ceremonies) must be determined through a more detailed investigation.

However, I know of quite a few examples where, in some exceptional situations, guilty respect for other people of authority is turned into its opposite. First, I should mention the joking relationships (gbieri or ale chaab leka; literally ‘insulting each other’) that can exist among the Bulsa between individuals, clan sections (e.g., Sandema-Choabisa and Longsa) or with foreign tribes and peoples (e.g., Bulsa-Zaberma). Permissive behaviour towards a pregnant woman after her pregnancy has been mentioned in this context of joking relationships, and the disrespectful behaviour of a wedding group of young boys towards, for example, the heads of compounds (yie-nyam) in songs has already been referred to. Perhaps the outwardly ‘impertinent’ but fully institutionalised behaviour of a bride’s brothers in the groom’s house {p. 276 ff.} also belongs to this framework.

The {340} chapter on wen ceremonies hints at a role reversal within a family. As described, the wen of a young child may assume the position of a ruler among all the wena of the house, even if the child continues to owe obedience to his father. It has also been mentioned that, for example, a ten-year-old boy (e.g. Ayomo Atiim in Leander Amoak’s house) can ritually assume the office of yeri-nyono if the funeral celebrations of the most recently deceased head of the household have not been held. Such a boy, typically the deceased’s youngest son, is the only household member entitled to offer sacrifices to the ancestors, even if older men live in the house [endnote 31].

A clear example of ritual permissiveness is demonstrated in sexual taboos being lifted at great festivals {285}. As mentioned, on this occasion extramarital sexual intercourse of wives is less disfavoured, and there are also relaxations in the exogamy rules.

In assessing the examples of licence in rituals listed here for the Bulsa, I join M. Gluckman in considering these ritualised ways of acting not as symptoms of disintegration but as a psychological release valve [endnote 32]. Only a fully functioning social system can safely allow freedoms for a limited time that could otherwise wreck a social order. As a psychological release, they strengthen acceptance of the established system.

4. TRADITIONAL RITES IN MODERN SOCIETY

So far, this work has noted that rites of passage can have a conflict-inhibiting character. However, in more recent times and among the more-or-less Christianised younger generation, these rites have largely lost their conflict-inhibiting character. Indeed, now they can have a conflict-producing effect. This may, for instance, be the case if a father forces his son or daughter to perform traditional rites against their will {341}.

According to my inquiries, conflicts over participation or non-participation in traditional ritual acts (e.g. the erection of a wen-bogluk, excision, performance of traditional marriage rites) are among the most frequent causes of conflict between schoolchildren and their illiterate fathers; in the case of school-leavers, financial disputes over the division of self-earned money are probably more prominent. However, this is not to say (as I had assumed before starting my fieldwork) that conflicts between school-educated children and their illiterate fathers are always much greater in principle than between illiterate children and illiterate fathers. Instead, the new generation of schoolchildren and school-leavers have other means of conflict avoidance and mitigation.

While complete isolation of certain persons {p. 337f.}is difficult to realise within a compound, and only for a short time possible, students enjoy their self-chosen absence from traditional life because schools are usually kilometres away from the parental compound. An illiterate father hardly dares to enter a school building to contact teachers or talk to them about his child’s educational difficulties.

There will also be less tension between older students and their fathers over internal matters of the home (e.g. the father’s jealousy over his son’s flirtation with his younger wives, the son’s usurpation of father’s rights, etc.) because the pupil has largely lost interest in compound affairs. After leaving school, he usually plans to travel to southern Ghana for several years.

Moreover, the student lives in a community of unrelated male and female peers and does not need any public funeral celebrations to have contact with non-related prospective spouses. Conversing with his classmates encourages him to recognise his conflicts with relatives, a task that used to be fulfilled partly by rites in the traditional surroundings {cf. p. 337}.

In addition to the ‘we-consciousness’ of persons of common descent, the group of peers with shared interests and goals has stepped in for the student. With these peers, he copes with common problems {342} (e.g. school life, exams), performs everyday religious acts (e.g. the daily morning prayer, Sunday service), participates in joint events, and celebrates festivities (e.g. football games and dance events at school).

If, in the new, ‘modern’ way of life, the old rites have lost a large part of their former significance and have generally been replaced by new religious (Christian) rites or diluted by new attitudes to life and ways of acting, the following question arises: Do the rites of passage, as an exponent of the traditional world, still have a chance of survival in the modernised society of the younger generation today and in the Bulsa society of the future? Indeed, this question cannot be decided similarly for all rites. It is already apparent today that various rites of passage are more or less viable or outmoded.

It is evident, for example, that the excision of girls and associated rites have lost much of their significance in recent years. Today many educated Bulsa girls do no longer understand the function of this practice because the reasons given (‘it has always been like this’; ‘otherwise I will make a fool of myself’; ‘otherwise I will be regarded as a man and receive a man’s funeral’) are not sufficient for most schoolgirls to undergo a dangerous, painful, and illegal operation.

The fates of the rites associated with wen-bogluta are closely linked to whether Christianity will displace traditional religion. Even if the Catholic mission currently tolerates somewhat generously that baptised people offer sacrifices to the wena, a genuine synthesis of Christian rituals and wen ceremonies is probably not to be expected.

The situation differs with naming and wedding ceremonies. Since names and marriage are not purely religious in nature, a synthesis between Bulsa traditions, Christian rituals and European secular institutions could take place. It has already been partially attempted for some wedding rites {cf. p. 301}, especially since a traditionally concluded Bulsa marriage is recognised as valid {343} by the Christian churches and the state of Ghana [endnote 32a]. However, traditional polygynous marriage seems to be a firm obstacle to Christianisation. None of the Christian churches allow a Christian Bulo to marry a second or third wife concurrently, and compromises for polygamously married Bulsa who want to become Christians are still not very satisfactory for both sides.

In the case of naming, simpler forms that forego divination and sacrifices seem to have emerged in acculturated or Christian families. Sometimes, non-Christian parents also give their child a Christian (English) name in the first days of life and catch up with a traditional segrika later. One may assume that the tendency to give a child a name right after birth will increase soon, particularly due to the newly introduced compulsory registration of births required by the authorities – the name of the newborn child must now be entered in birth certificates.

The cutting of tribal marks had already lost almost all religious-magical references before the invasion of the Europeans. Such reference can still be found – at least in rudiments – in applying navel cuts, in the bia-kaasung or Southern facial scars. The survival of the Bulsa scarifications seems to depend more on aesthetic and tribal patriotic considerations. The younger generation of students is largely dismissive.

The traditional rules of conduct during pregnancy and childbirth are followed very eclectically. Rituals regulating the relations of the pregnant woman or woman in labour with other persons (e.g., poi-nyatika and pobsika) are still practised quite frequently, even by Christian Bulsa. Christian missionaries have partly overtaken the public proclamation of pregnancy (cf. p. 63).

Non-Christian Bulsa also seem very open to the European-influenced wards’ medical advice and skills. The traditional food prohibitions for pregnant women, which refer to protein-rich foods, are often doubted in their usefulness. Hospital births, where the mother has mostly escaped the {344} influence of the yeri-nyono and the diviner, are becoming increasingly popular.

In light of these more hypothetical considerations about the fate of the traditional rites of passage, the conclusion must remain open, especially since most of the mission stations are still primarily led by whites (1978) and only a few African pastors experiment with combining traditional and Christian practices (e.g. by replacing the mass wine by millet beer). Thus, Christianity’s fate in Ghana depends also on political decisions by the central government in Accra. I am not aware of any broader nativist movements in northern Ghana that take up traditional religious ideas and old ritual practices to combine them with modern ideas [endnote 33]. However, they cannot be completely ruled out for the future: a new turn to traditional beliefs and a selective resumption of Bulsa rites and magical practices is observable among individuals after having spent their youth in the Christian belief.

ENDNOTES (CONCLUSION)

1. Only in the presentation of courtship and wedding ceremonies could older and newer customs be separated in this work.

1a. In 2013, I described the juik (mongoose) cult and its specific substructures for several ethnic groups in northern Ghana.

2 The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland, vol. I, 1969: 42–45.

3. This language family received its name from the languages of the Mossi (language: Mole) and Dagomba (language: Dagbane). In the table {p. 312}, the languages Buli, Mole, Dagbane, Mampruli (Mampelle), Nankane (Gurenne), Tale (Tali, Talene), Kusal and Dagari belong to this group. Kasem (Kasene) and Isal belong to the Grussi (Grunchi) languages.

4. P. 43: tib-yin.

5. ‘Terminologie religieuse au Soudan’, L’Anthropologie, 33 (1923), pp. 371–83.

6. ‘A study of Kusase religious beliefs’, Evangelical Missions Magazine, 108 (1964), p. 149.

7. As Buli does not yet have a standard way of writing, the [γ] sound is written in different ways. In this work, it was rendered by ‘g’, as is also practised by most literate Bulsa. Other possibilities would be ‘gh’ (currently not very common in Buli) or γ (with typographical difficulties).

8. Cf. K. Dittmer, Die sakralen Häuptlinge…, p. 139 and the introduction to the present study, p. 17f.

9. ‘A Cross-cultural Study of Female Initiation Rites’, American Anthropologist, 65 (1963), pp. 837–853.

9a. Victor Turner (1967: 50f.) distinguishes three symbolic levels: 1. the level of indigenous meaning, 2. the operational meaning, and 3. the positional meaning. The first meaning can be inferred by questioning competent informants and the second by their practical application; the third level of meaning can be derived by comparison with other symbols of the social system. Turner’s classification of symbols can also be used to outline the symbolic content of Bulsa rites.

10. Cf. J. Brown, p. 843. The author largely follows John W.M. Whiting (1961) in her argumentation.

11. E. Haaf (Die Kusase, p. 51) reports that the Kusase (Kusasi) adopted the custom from the Busanse {373}. Knudsen’s (1994) statements seem quite reliable, as she has intensively examined excisions in northern Ghana through numerous visits, interviews and observations. According to her, female excision occurs among the following ethnic groups: Bimoba, Awuna (Kasena), Konkomba (only in a few lineages), Mo or Dega, Pantera (Nafana), Safalba, Tampulensi, Vagla, Lo-Dagaa and Lo-Wiili, Dagaaba, Sisaala, Wala, Wa, Kusasi, Busansi, Frafra, Tallensi, Bulsa and Nankanni. Female excision is not practised among the Bassari, Chakosi, Dagomba, Gonja, Mamprusi and Koma.

12. The Andaman Islanders (The Free Press of Glencoe,1964), p. 230.

13. Cf. the quotation in the introduction to this study, p. {23}.

14. Additional major sacred acts (e.g. sacrifices to the ancestors) associated with many rites of passage but whose meaning is easily deduced from the ritual context have not been included in the following overview.

14a. Before a divination session, the client takes two small sticks or stalks, rubs them over the divination bag, and throws them away. This action is called piirika and is usually translated as ‘purification’. It intends to cleanse the diviner’s utensils of all evil influences from the previous session. It involves saying, for example, ‘Tanggbana, ti-baasa ale baan-bisanga ale jo fi jigi la, ba la miena daungta al n piiri a basi’. Translation: ‘Earth shrines, evil medicine and [the influences of] clients who came to this place; I cleanse and remove all their filth’.

15. While the red-black waist cords consist of two red and two black cords, the black-purple cord is bicoloured. The purple dye is obtained from the leaves of a particular type of bean. Cf. Ethnographic Bulsa Collection of the Forum der Völker, Werl).

15a. For example, she is entitled to an individual courtyard in the compound if space allows.

15b. S. Dinslage (1981: 138–141) devotes a separate sub-chapter (9.8) to colour symbolism in girls’ excisions among the Ubi, Bambara, Gurma and Bulsa.

15c. E. Haaf 1967.

16. A small distribution map for Africa, perhaps needing improvement today, can be found in L. Frobenius, Monumenta Africana (Frankfurt, 1929), p. 117. Frobenius attributes this assignment of numbers (3 = male; 4 = female) to the Syrtic culture.

17. A.W. Cardinall (Tales Told in Togoland, 1931: 62) could not discern an explanation for the number of assignments. Cf. also C. G. Jung (Bewusstes und Unbewusstes, Frankfurt and Hamburg 1957, pp. 75, 121f. and 132); E. Haaf (Die Kusase, p. 29) describes the triad and tetrad as archetypal structures. Cf. also F. Herrmann, Symbolik in den Religionen der Naturvölker (Stuttgart, 1961), p. 246 ff.