CHAPTER VII

COURTSHIP AND MARRIAGE

1. MARRIAGE BANS

Marriage bans occupy a crucial place in the social order of the Bulsa. I have often been assured that a transgression of an explicit marriage ban is one of the most shameful things a Bulo can imagine.

As a general rule, I was told that people who sacrifice together to an ancestor or ancestress cannot marry each other. However, this rule does not apply if the ancestors or ancestresses lived a sufficiently long time ago. Thus, a man from Wiaga-Kubelinsa can marry a woman from Abapik Yeri (Wiaga-Badomsa), even though Kubelinsa sacrifices to Abadoming’s mother (the section founder of Badomsa) in Abapik Yeri.

a) Marriage bans for large groups

By this type of ban, I refer to prohibitions that a single individual has in common with segments of his lineage or with groups beyond a clan section. Moreover, marriage prohibitions of an individual related to a larger group, such as another clan section, will be discussed here. The distinction between these and the ‘individual marriage bans’ listed below is fluid and has been made here more for work-related reasons. The most fundamental marriage bans that apply to large groups are:

1. A Bulo may not take a wife from his father’s own clan section, i.e., his clan section. The ambiguous term ‘section’ (English: section or division, Buli dok or yeri) requires further clarification. The following social units can be understood under this term {242}:

a) Exogamous clan sections. These usually comprise the patrilineal descendants of a lineage founder who lived about 7–10 generations ago and after whom the section is usually named (e.g., Kalijiisa after Akaljiik). Inclusions of smaller foreign lineages (assimilated or attached lineages in the sense of M. Fortes) [endnote 1], which may, for example, trace their origin back to a slave, usually respect the marriage bans of their host section (cf. p. {254}).

b) Local groupings. On the surface, these ‘sections’ are often already recognisable by the fact that their names cannot be derived from a founder but instead have a descriptive character, e.g. Yipaala (new houses), Yisobsa (dark houses), Yimonsa (red houses), Belezuk (by the river), Goluk (valley), etc. Of course, such local units can simultaneously be exogamous clan sections.

c) Administrative units. Most likely, the administrative sections under a kambon-naab (English: ‘sub-chief’ or ‘headman’), created within the web of lineages, were not made until the British colonial administration began. These sections often combine several smaller exogamous clan sections. The following administrative sections of Sandema, for example, consist of two or more exogamous units – usually called subsections in such a case – which are mainly allowed to intermarry within the same administrative unit or section:

BALANSA. Subsections: Akuriyeri, Anyabasiyeri, Apaabayeri, Bagunsa, Banyinsa, Banyimonsa, Daborinsa, Sanwasa, and Yiriwiensa.

BILINSA. Subsections: Bilinmonsa, Bilinsobsa, Farinsa, Pungsa, and Tankunsa. Bilinsa-Pungsa and the Sandema-Fiisa section do not intermarry. A Fiisa man does not even marry the daughter of a Pungsa woman.

KALIJIISA. In the past, Kalijiisa was divided into two exogamous units, namely Choabisa, the section of the blacksmiths, and Kalijiisa in the narrower sense. Marriage prohibitions between these units have only been lifted quite recently.

KANDEM. Subsections: Kanwaasa and Tolensa.

KORI. Subsections: Apaisibasi, Belingmai, Kanaansa, Katuensa, Kori (in the narrow sense).

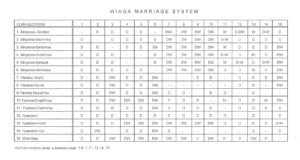

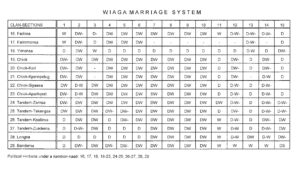

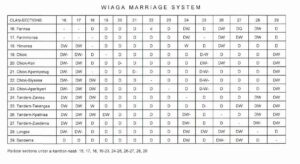

In Wiaga, too, some administrative sections (e.g., Chiok, Sinyansa, Tandem and Yisobsa) consist of several exogamous clan sections (cf. table ‘Wiaga’s marriage system’, Chapter VII, 1a, p. 248).

On the other hand, there is (or was) often a ban on marriage between politically independent sections, as the kinship relationships between these groups are still considered too close. In Sandema, for example, marriage between the Kalijiisa, Kobdem and Longsa sections was forbidden until the 1950s; even today, many men in these areas are reluctant to intermarry.

In Sandema-Kalijiisa, marriage was forbidden among all subsections, including the immigrant blacksmith subsection, Choabisa. At an old man’s funeral (in 1973), an elder announced that marriages between Choabisa and the other subsections of Kalijiisa would henceforth be allowed. This announcement took several years to be widely accepted. In one case, when a young man from Choabisa courted a girl from another Kalijiisa section, it aroused general merriment before his rejection, and people gossiped that ‘someone wanted to marry his sister’.

In Wiaga, there was a marriage ban between Yisobsa and Farinmonsa ‘in the time of the grandfathers’, which has been unilaterally lifted in recent years. Although many Farinmonsa men do not scruple about marrying an unwed Yisobsa woman, Yisobsa continues to abide by the marriage ban (in 1974).

In Wiaga-Sinyansa, marriage was banned between its (sub)sections until the 1950s; the ban on those with a common ancestor (Badomsa, Kubelinsa and Mutuensa) lasted the longest. Today, almost all sections intermarry. Only between Kubelinsa and Mutuensa, which is sometimes referred to as a subsection of Kubelinsa, does the ban still exist.

2. A Bulo is usually not allowed to marry a woman from his mother’s clan section. However, there is an exception: Suppose a woman of his maternal section grew up outside the section territory (e.g. in southern Ghana) and will continue to live there with her husband. In that case, their marriage is allowed if the groom’s wife and mother are not from a too-small or close segment of their common lineage. Marriages from the sections of an individual FM (paternal mother) [endnote 2], MM, FMM and MMM are often also mentioned by informants as not permitted. Still, in practice – especially if large sections are concerned – these unions are often limited to a somewhat smaller segment of the lineage within that section.

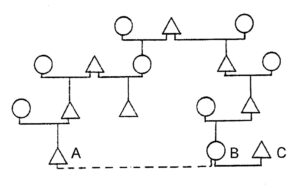

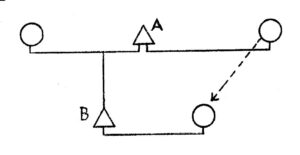

In addition, marriage restrictions sometimes refer to groups with no blood relationship, even according to European concepts. Thus, a Bulo (A) cannot marry a girl (B) from the house of his FFWF without further ado (cf. genealogical sketch below), as the girl’s parents would never give their consent. He (A) can abduct her (B) against the will of her parents but must accept that, in the case of a later separation of the marriage, the wife (B) {244} will return with her children to her parental home; if she marries another man (C), husband A will have even more significant difficulties in getting his children back, since he cannot count on the help of his parents-in-law.

There is often disagreement about whether a groom is still too closely related to his bride in the female line. In this case, lively discussions ensue. Whether the marriage was correct often only becomes apparent after a few years, such as when no children are born or the marriage suffers other misfortunes. If one discovers afterwards that one is married to a close matrilineal relative, e.g. a grandchild of the same grandmother, the marriage is usually dissolved unless children have already been born between the husband and wife. However, the impression must not be given that marriages into a matrilineage are avoided only because of the possible lack of child blessings. I have been assured several times that such marriages are also considered immoral outside these concerns.

No discussion as to whether marriage to a matrilineally related person is permissible will arise if the groom’s family has taken a ma-bage from the bride’s compound. The bride and groom, especially if they had eaten from the soil of this shrine, would die immediately, and further blows of fate could befall the two families (cf. p. 178).

3. Although until now, only too-close family relations have been cited as reasons for prohibitions of marriage between larger groups, enmity (dachirini) between two groups is also an obstacle against marrying a ‘daughter’ (Buli lie), i.e. a female member of the other section. Once the social relations {245} between two sections have been disturbed, for example, by murder, they cannot be much worsened by further hostile acts, such as the marriage of a wife of a third section who was already (or is) married in the hostile section, even if such marriages help perpetuate the poor relations between the two involved sections. In today’s Wiaga, the initial reason for bad relations between two sections is often forgotten, and people only refer to the feuds of past times. The exact distinctions between sections from which one is not allowed to marry at all and from which one is allowed to marry ‘daughters’ (lieba, sing. lie), already married women (pooba, sing. pok) or ‘daughters’ and (or) ‘wives’ has led to a complex marriage system in Wiaga, depicted in a table below.

Sometimes, the elders (kpaga, sing. kpagi) of a section must intervene and force a member of their lineage to yield, as the following example shows:

In 1966, a man from Wiaga-Yimonsa married a woman married in Sinyansa (Bachinsa?). Later, a young man from the same Sinyansa section took a ‘daughter’ of Yimonsa home as a bride, probably against the wishes of his section (Sinyansa). Consequently, the Yimonsa elders arranged for the ‘wife’ to be returned to the Sinyansa section.

If, on the other hand, someone marries a ‘wife’ of section N, it follows that no other person of his section may marry a ‘daughter’ from section N before some time has passed {246}.

As the examples have shown, marriage opportunities between sections in a locality (e.g. Wiaga) are not rigidly fixed. Instead, they are subject to change over time. The continued marriage of ‘wives’ from one section may thwart the marriage of ‘daughters’ for a long time.

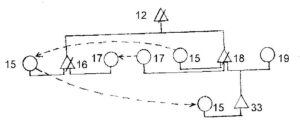

The following table (1973–74) contains information from exclusively older or ex officio knowledgeable men (e.g. almost all kambon-nalima of Wiaga). According to my instructions they were interviewed about their section by Clement, the now-deceased son of the Wiaga chief, Asiuk. However, the overview still reveals numerous contradictions. Apart from other reasons, these contradictions can be explained by the vast number of ‘foreign houses’ in many political sections, i.e. kinship groups that do not belong to the section’s central lineage. Moreover, in the interviews, political sections have frequently been confused with lineages. Sometimes, a marriage ban with a certain section is also reported because the informant is personally related to this section through the female lineage (although the older men should be made aware of this error by my assistant).

As the Yisobsa-Farinmonsa example above (Chapter II, 1a; p. 243) shows, misinformation cannot automatically be inferred {247} if the table shows that section A marries from section B, but section B does not marry from section A.

Notes and abbreviations for the following tables (Wiaga’s marriage system):

D (for daughters): Only ‘daughters’ (yeri-lieba, daughters of the compound or lineage) from this section are married.

W (for wives): From this (hostile) section, one marries only married women (who, of course, come from a third section by birth).

DW: From this section (e.g., from different sublineages), ‘daughters’ or ‘wives’ are married.

D-: From this section, ‘daughters’ are married only with restriction, i.e., not from all subsections or parts.

W-: Only from certain parts (subsections) of this section are wives married.

– From this section, one does not marry ‘daughters’ or ‘wives’ (for reasons of too near kinship).

Wiaga marriage system I

Wiaga marriage system II

Wiaga marriage system III

{249} In Sandema, such a complex marriage relations system is largely unknown. Sections that marry only ‘wives’ of each other seem to be exceedingly rare; I am only aware of Kobdem and Kori. Sections that have recently abandoned their mutual marriage ban (e.g. Kalijiisa, Kobdem, Longsa) only marry ‘daughters’ of each other.

Even murder cases and feuds have not led to long-term marriage bans between whole sections of Sandema. A member of Kalijiisa killed a man from Chuchuliga some time ago. I was told that in the initial period after the manslaughter, the two concerned sections generally did not intermarry. Today, this prohibition exists only between the specific houses to which the murderer and the killed person belonged.

It may be worth investigating further whether a connection exists between joking relationships and marriage bans due to enmity. In Sandema, unlike Wiaga, there is a distinct system of joking relationships (gbieri, v. or ale chaab leka, v.n.) between individual sections. As I have often been assured, joking relationships may arise from former enmities or feuds. The joking relationship between Bulsa and Zabarima – the ethnic group of the notorious slave raider Babatu [endnote 3] – also supports these claims. In one case of joking relations between two Sandema sections, the origin allegedly goes back to a murder case. The assumption that in Sandema, former enmities express themselves through joking relationships, while in Wiaga, they are expressed through marriage bans of ‘daughters’ or permitted marriages of ‘wives’, cannot yet be proven [endnote 4].

In most smaller Bulsa villages, such as Siniensi, Kadema, Gbedema and Kanjaga, it is generally forbidden to marry someone else’s wife from the same village. A young man from the Siniensi chief’s house explained that a small village with only a few sections cannot afford to let quarrels arise among its inhabitants. If a man from Siniensi has married a woman married in Siniensi before {250}, he must either give her back or leave Siniensi with the woman. Neither are strangers of the village allowed to marry a woman already married if they want to keep their residence in Siniensi.

Since the chiefs of Sandema and Wiaga want to get along well with all lineages in their village, they are also forbidden to marry wives from their village.

In Uwasi, the supposedly older lineages may only marry ‘wives’ from those that later settled in Uwasi as foreigners (Angmong Yeri, Wasik, and Achang Yeri). It is similar in Doninga, where ‘daughters and wives’ can be married only from Yipaala-Kong, a foreign subsection where they still speak Sisaali.

In Wiesi (Wiasi) and Fumbisi, too, people only marry ‘daughters’ from most other sections. Still, in both localities, there are also sections from which people only take married women, without these sections being proven to be foreign groups.

Earlier, the rules of individual marriages with enemies (dachaasa) applied to marriages from hostile ethnic groups. All foreign tribes had to be regarded as potential enemies, and marriage was risky. Nevertheless, marriages with people from other ethnic groups were also likely occurrences of sufficient frequency in earlier times. During his field research, M. Fortes [endnote 4a] learnt that the Tallensi Bangam Teroog went to Sandema 50–60 years ago and met relatives everywhere along the way who welcomed him as their guest.

4. Marriages between certain groups are also forbidden for reasons that may be described as part of politico-ritual.

Some years ago, Robert Asekabta, a Sandemnaab (Abilyeri) relative, applied to marry a young girl from Suarinsa-Niima. It was known that Robert and his family were unrelated to Suarinsa. Nevertheless, his father had to enlighten him that he could not marry this girl because men from the Suarinsa-Niima subsection were involved in installing the chief. Since the chieftaincy house had already received a ‘daughter’ [endnote 5] from Suarinsa-Niima, namely {251} the chieftaincy, a member of the chief’s house could not demand another ‘daughter’ from the same subsection.

b) Individual marriage bans

In addition to the exogamy rules of entire groups, the individual still must observe marriage prohibitions resulting from their unique position in the kinship system.

1. A man shall not marry two daughters of the same father and mother if they were born directly one after the other in the order of birth [endnote 5a]. If this has nevertheless happened, the two wives must observe a whole series of rules. For example, they must not sweep out their living quarters at this time and must use different entrances to the compound. If the mother of these two daughters had a stillbirth between their births, the aforementioned marriage prohibition remains in force. However, if a child born between the two daughters lived for a while and then died as a baby, the marriage prohibition described above does not come into force.

Even two full sisters with other living siblings in birth order should not marry the same husband if possible. G. Achaw believes that the husband’s obligation to the in-laws’ house becomes too great otherwise: He would have to help his parents-in-law with the field work twice yearly (one day for each wife). However, such cases rarely happen. If, for example, the funeral service of the two sisters’ father is held, the house from which the two sisters come will be worse off, as the two sisters’ husband will contribute to the funeral service only once. G. Achaw (Kalijiisa-Yongsa) already had substantial difficulty in getting the consent of his bride’s parents to marry because a man from Kalijiisa {252}-Choabisa had married one of the girls’ sisters, even though Choabisa is a ‘foreign’ subsection and can now marry those from Yongsa.

2. A man and his sister who immediately follow in terms of birth order may not marry a daughter and son of the same parents (Inf.: G. Achaw).

3. A man may not marry a daughter from a former marriage of his father’s wife if he grew up with this daughter. If this girl has grown up in her father’s family, a marriage usually does not occur because the two families are enemies (cf. Chapter. VII, 1a; p. 244).

4. After performing a ma-bage ritual, a marriage ban will exist between the host compound’s and guests’ families (Cf. Chapter V, 3d; pp. {169–173}).

c) Violation of a marriage prohibition: an example

Non-compliance with an explicit prohibition of marriage is neither a private matter nor a misstep forgotten after a few years. Such a transgression is, according to Leander, ‘the only mortal sin we Bulsa know’. The lives of the whole group are threatened in such a case, which will be illustrated by a case of kabong (pl. kabonsa) in Wiaga-Sinyansa-Badomsa, the story to which Leander made me privy. Kabong is a particularly grave variant of adultery.

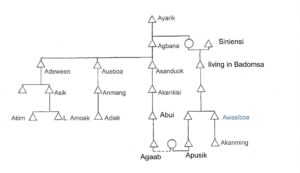

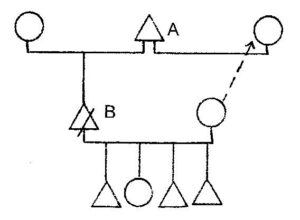

Around the year 1950, a certain Agaab (name changed) from Badomsa married the wife of Apusik (name changed) from Siniensi. The woman was from Kubelinsa and could have married a Badomsa man before marrying Apusik. The kinship relationship between Agaab andApusik can be depicted as follows:

Violation of a marriage prohibition

{253} The Siniensi family is related in the female line to the descendants of Ayarik because the children of Ayarik’s daughter came to Badomsa to live in their mother’s section. Only Apusik’s father left Badomsa again to move to the section of his patrilineage. The kinship relations between Agaab and Apusik were such that Agaab could probably have married a daughter of Apusik without difficulty. However, marrying a wife from a lineage to which one was related through a woman and of whom one family branch lived in Agaab’s section is considered kabong. Akanming, the head of the Siniensi lineage in Badomsa, thus reported this action to Anmang, then the elder of the Ayarik-bisa, who had to sacrifice to Ayarik’s wen. Anmang (who is said to have been over 100 years old at the time) sent his son Adiak to Abui, demanding that his son Agaab immediately return the woman.

Abui, however, did not react. He allowed his son to keep the woman and thereby made himself complicit. ‘This, in fact, became family adultery, and it is a dirty affair [endnote 5b] among our ancestor[s]’ (Leander told me). Anmang soon died (of natural causes), and Ayarik’s and Agbana’s bogluta passed to Abui, the next eldest of the Ayarik-bisa line. Without having cleared the offence, he sacrificed to Ayarik and Agbana. As a result, three days later, he was paralysed and died after a week. The wena were passed on to Atiim (Leander’s brother), the next eldest of the lineage (Ayarik-bisa).

When Abui’s brothers transferred Ayarik’s and Agbana’s bogluta to Atiim, they did not inform him what had happened in their family. Atiim sacrificed to the wena and died after a few days. Then, Leander took Atiim’s place. He consulted a diviner and finally learnt from him what a dangerous situation he was in. He stopped all acts of sacrifice to Ayarik and Agbana and gathered the elders from Ayarik’s line. Asandiok’s family admitted their guilt, and they promised to send the woman back. After this, Leander (through his nephew Ayomo Atiim) offered chickens and millet water, all provided by Asandiok’s descendants, as an expiatory sacrifice to Ayarik and Agbana. However, these ancestors refused this sacrifice. The diviner discovered that chickens and millet water were insufficient for such a severe offence. The ancestors demanded a larger animal (dung, pl. dungsa), i.e., a goat, sheep or cow. {254} to which Asandiok’s descendants agreed. According to L. Amaok’s latest information (1980?), the matter would soon be wholly settled [endnote 5c].

d) Summary

Marriage bans generally exist for the following four reasons:

1) Kinship proximity

2) Enmity

3) Political interdependence

4) Local and emotional proximity

Re 1) Only from this first factor has a genuine taboo developed, which, if not observed, entails automatic sanctions (e.g. miscarriages, quarrels, misfortune) and sanctions from the section (e.g. expulsion).

Re 2) Marriages between hostile families are hardly conceivable for the Bulsa because a marriage contract is supposed to strengthen friendships between families and sections or create new friendly relations. A son who wants to marry is expected to respect not only friendships but also the enmities of his father or his group.

Re 3) I am only aware of one example of marriage bans for reasons of political entanglement that were described above (Abilyeri – Suarinsa-Niima). Further research on similar ideas in other chiefdoms would undoubtedly be worthwhile.

Re 4) The fourth factor sometimes has only a modifying effect, such as when a man is allowed to marry a distant relative from his mother’s section in southern Ghana but not within his father’s section in the Bulsa area, where his mother lives or has lived.

Local proximity is also significant when foreigners settle on the territory of a section. In Kalijiisa-Yongsa, there are two compounds whose ancestors came from South Bulsa a long time ago (at the end of the 19th century?) and settled here during warlike conflicts. They {255} still respect other totem animals of their former home (e.g., fiok monkey instead of waaung monkey) [endnote 6]. Nevertheless, no one from Yongsa can marry into or from these houses.

This marriage ban, in the case of resettlement, does not come into effect immediately after the move. I was told that around the time of the death of the last housemate who still bodily witnessed the resettlement, the time for a marriage ban with the host section had come. However, the house dwellers’ emotional (and probably political) attachment likely plays a role. The two houses in Yongsa had lost all contact with their home section after their resettlement, and today, they (allegedly) no longer know which section they came from.

Today, in any case, they consider it an insult to be told that they are not Ayong-bisa. Nevertheless, the three offshoots that seceded from the chief’s family in Sandema-Abilyeri, who have found a new residential section in Suarinsa, still regard themselves entirely as members of Abilyeri.

The principle of local and emotional proximity as an obstacle to marriage is not always observed. Even though the marriage of a father’s divorced wife by his son would be inconceivable during the father’s lifetime, the sons are allowed to marry the father’s wife or wives after his death and funeral if she is not their biological mother or a woman from their own mother’s section. The local and emotional closeness between the son and the father’s wives is shown in living together and in the fact that the son called these wives ‘mothers’ (maba) while these women often performed maternal functions towards him.

For the rarer case (and a very controversial one in the lineage) of a father marrying the deceased son’s wife, I have encountered one example in Sandema-Kalijiisa.

Moreover, when a little girl is taken into a house as a doglie [endnote 7] and grows up almost like a sister with her age-mates in the house, in order later to be given to one of these children as a wife, marriage is contracted, although emotional, kinship-like relations {256} of a non-sexual kind already existed beforehand.

Among the Bulsa, no prescribed or particularly recommended marriage unions exist, such as cross-cousin marriage among many Akan peoples. Nevertheless, genealogical studies show the following two tendencies in the choice of partners:

1. There is a tendency in polygamous marriages to take more than one wife from the same section. In many of the cases studied, it may well be that an older wife took a younger girl from her family or relatives as a domestic servant (doglie) to offer her to her husband as a wife when she is of marriageable age. The reasons against brothers marrying from the same section as given above (Chapter VII, 1a; p. 251) speak against this custom, especially if the women come from the same house. Of the 69 women married into Yongsa, [endnote 8] for example, 5 come from Abilyeri, who a few years ago all lived in the same house (Abiako Yeri). Of one of these women, I know that she came as a doglie. In Akumkadoa’s compound, three of the four wives of the compound head, are from the same section in Siniensi. Is it a coincidence that the three women who married into a Yongsa house from Wiaga are all from the Chiok section?

For the Tallensi, M. Fortes has shown [endnote 9] that women preferably marry those from geographically close areas and that tribal borders are also crossed [endnote 9a]. This will be tested for Yongsa, a Bulsa subsection. As I realised too late, Yongsa is not particularly suitable for a representative study for the following reasons:

a) More than other sections of Sandema, the men of Kalijiisa, especially Yongsa, have devoted themselves to the kola trade and thus come to distant areas more often than the young men of other sections.

b) Yongsa borders sections to the south and southwest (Kobdem and Longsa) from which Kalijiisa was not allowed to marry women a few decades ago. Even today, quite a few men avoid {257} entering such a marriage. Thus, investigating whether Yongsa men prefer to marry women from neighbouring sections is challenging. Yongsa borders other subsections of the large Kalijiisa section to the northwest, north and northeast, separated from Chana by a strip of bushland about eight kilometres wide to the north. To the west, Yongsa is adjoined by a few houses in the Kalijiisa-Chariba subsection, followed further west by one of the largest uninhabited savannah areas in Bulsaland. The only border section from which Yongsa men are allowed to marry women is Bilinsa (Tankunsa) to the southeast.

The following overview shows the localities and sections from which Yongsa men took their 69 wives (cut-off date: 1 July 1974).

A) Bulsa: 56 (women)

1. Sandema: 36

a) Bilinsa: 14

Tankunsa: 7

Pungsa: 4

Bilinmonsa: 2

Bilinsobsa: 1

b) Balansa: 6

c) Abilyeri: 5

d) Nyansa: 4

e) Suarinsa: 3

f) Fiisa: 2

g) Kandem: 1

h) Kalibisa: 1

2. Siniensi: 9

3. Chuchuliga: 4

4. Wiaga (-Chiok): 3

5. Fumbisi: 1

6. Gbedema: 1

7. Uwasi: 1

8. Kadema: 1

B) Kasena:

Chana: 13

Despite the concerns outlined above, the investigation in Yongsa has produced the following results:

1. More than 60% of all women married into Yongsa houses come from the same locality of Sandema {258}.

2. The ethnic border (Bulsa-Kasena) has proved to be less of an obstacle than the great distances to other Bulsa localities: Kunkwa, Kanjaga, Doninga and Wiesi are not represented at all; Fumbisi, Uwasi, Gbedema, and Kadema are only represented by one woman each.

3. The only Bulsa section adjacent to Yongsa from which women could be married without restrictions in the past ranks at the top of all Sandema sections. It is Tankunsa in Bilinsa, the subdivision next to Yongsa, where proportionally, most Bilinsa women were married off to Yongsa men. Within Yongsa, the house directly bordering Tankunsa (Amoanung Yeri) has the most marriages from this subsection (three women).

2. COURTSHIP AND MARRIAGE

a) Marriage without courting [9b]

A marriage union can come about almost entirely without courtship, such as when a married woman brings a young girl from her kinship into her house as a domestic servant (doglie) and later gives her as a wife to her husband or another man of the house. As has already been described (1,3: p. 41), such authorisation of the married woman over a younger relative can be ritually justified, such as when the ceremonies of putting on the waist string of a pregnant woman are performed. Notably, however, the mere fact that a young relative helps the wife gives her powers over the girl.

The husband’s consent is the prerequisite for establishing a new marriage union, but a ‘no’ will rarely come if the man is willing to live in a polygamous arrangement. The girl herself can express her contrary wish to marry another man of the house; if one does not respect this wish, one may expect the girl to flee to her parental home {259}, which also happens if she wants to marry a man from another section. In one case I know of, the parents exerted no further pressure on the returned girl to marry a man of her choice.

In Yongsa, Abiako Yeri, the wife of an over 70-year-old compound head, has taken a female relative of about 3–4 years from her section into Abiako Yeri. There is no thought of the her marrying the yeri-nyono, but later marriage to one of his adult sons, who now care little for the young child, is not ruled out.

b) Getting to know each other and courting (lie-yaaka or dueni deka)

In traditional Bulsa society, markets and large festivities, which representatives of other lineages and sections attend, are the prime occasions to seek a marriage partner of one’s choice.

The latter include harvest festivals [endnote 10], funerals for the dead of great personalities and weddings. The older generation usually does not object to the secondary purpose of these events as a marriage market. At the funeral of a great warrior in Sandema-Choabisa, an old man made a speech in which he wished that all the present bachelors would find a spouse. It was demonstrated above that further marital links are easily forged between the two clan sections at weddings and subsequent visits.

However, the actual meeting place for young people eager to marry is the market, which occurs every three days in most Bulsa villages. Here, a young man who has often admired a girl he does not yet know may be able to meet and begin courting her. The following characteristics of unknown girls that arouse admiration, affection and desire for marriage were frequently mentioned by male informants {260}:

1. Beauty

2. Physical strength and ability to work

3. Health

4. Fitness for childbirth and child-rearing (wide hips and not-too-small breasts)

Generally, Bulsa men report that a healthy-looking, strong and not-too-thin girl with pronounced feminine features is seen as beautiful. A light brown skin colour and a small gap between the upper incisors are also considered special beauty features.

It is relatively common for a young man to spontaneously fall in love with a girl without being able to describe his motives. As an example, a part of the life story written by a 20-year-old man from Wiaga-Yisobsa-Guuta is quoted below:

Now the last and most interesting is Agnes from Kania… I got to know this girl at a native dance in Accra, the capital city of Ghana. They were dancing in the name of a new chief who was selected to look after the Bulsas in Accra. As the marvellous drums were in action, this girl jumped [into the circle of visitors] and started dancing. All the people around her were so surprised that [each] Tom, Dick, and Harry [were] clapping hands and placing money on her forehead. I was compelled to pull out a cedi and place it on the girl’s forehead, as it is done according to our traditional activities. So, on that very evening, I started to discuss love matters with the girl. She also became interested in me, and we started corresponding through letters… Although I am not yet married, I cherish the hope that sooner or later, I will marry. My mind is telling me that my future wife will be Agnes.

Some young Bulsa men emphasise that it takes a great amount of courage to approach an unknown girl; sometimes, they feel too shy to approach whomever they admire. A point of contact for a first conversation does not always present itself. In this scenario, G. Achaw believes that a good trick is to prove the girl wrong {261}, saying, for example, that she bumped into the applicant and did not greet him or something similar. If the young man is too shy, he can ask his friends to help him. G. Achaw writes:

I went and told my companions and showed them the girl, and they called her and spoke to her because it is not my companions who are after her, and, as such, they don’t fear her. When my companions spoke with her, they found out that she was [too] shy to speak. She could not stand before many people to speak.

Along these lines, Augustine Akanbe describes a first interview as a suitor might have at the market. Although everything is presented almost as the norm, this recollection may be autobiographical.

He will have to ask, ‘Hey girl, are you a daughter of the house where you come from? Or are you a wife to that house?’ The girl will not answer him at first, but she will put a return question to him: ‘What do you mean by that? Do you want me to be a daughter of that house, or do you want me to be a wife of that house?’ The man will then say to her: ‘My reason for asking you these questions is that I love you, as I saw your face.’ The girl will then say: ‘I see. What do you mean by love? Do you love me to be your girlfriend, or do you love me to be your main friend?’ The man will say to her: ‘I love you to be my future wife, but if you have a husband, and as I saw your face, I shall still love you to be my main friend.’

Note: By main friend (Buli: pok-nong), Augustine means the friendship between a married woman and a close friend, of which the woman’s husband knows and to whom he has consented. In return for the usually ‘platonic’ love, the suitor does some field work for the married woman and her husband. As the quoted conversation shows, the reason for a pok-nong relationship is sometimes a marriage prohibition. If a woman desired by a man is not allowed to marry the suitor because of a too-close relationship, he may still be able to win her as his pok-nong {262}.

G. Achaw’s remarks and the dialogue quoted by Augustine show that the girl may not immediately respond to the man’s courtship. Depending on her temperament, she may be reserved or try to elicit more concessions from her partner without making a concession herself. The quoted dialogue also leads to the most decisive questions: whether the girl is already married and whether any marriage prohibitions speak against a marital union. The second obstacle is usually much more serious than the first. The suitor does not always ask the girl as directly as he does above. Often, he will make these inquiries from elsewhere, and his friends can help him with this.

On several market days, conversations may be held between the suitor and his friends on the one hand and the girl on the other until the crucial question comes: whether the suitor can go and see the girl’s parents. The courted girl has no right to answer this question in the negative; a positive answer, therefore, in no way implies an acceptance of the man’s courtship. In Augustine’s account, the suggestion for this visit even comes from the girl as a fallback answer to the question of whether she wants to marry the suitor:

Then the man will ask her: ‘Will you marry me, or don’t you like me?’ She will answer, ‘Why don’t I like you? Are you not a man? You are a man, and I am a woman. So, I have to like you, but you have to come and visit my parents and tell them that you have met me at this place, and you have begun to love me.’

Upon this answer, the applicant can hand the girl a small gift or give her money so that she can buy something for her parents to make them feel favourably towards his courtship.

c) Home visits

On the way to the girl’s section, the applicant and his friends are already subject to certain restrictions. If a huntable animal (e.g., a hare) runs across their path, they are not allowed to {263} kill it, and this prohibition also applies to further visits to the courted girl’s parents’ compound [endnote 11]. They contact a neighbouring house before the suitor’s group enters the girl’s parents’ house. The neighbour inquires about the following things in the house of the courted person (as far as he cannot give information himself):

1. Is a mat (tiak) being woven?

2. Is shea butter (kpaam) being prepared?

3. Is pito (daam) being brewed [endnote 12]?

4. Is a funeral being held?

5. Has someone died in the house who has not yet been buried?

If one of the five questions is answered with ‘yes’, the courting group must return immediately. If they nevertheless visited the woman’s house, she, the courting man, or both would die in the first period of their marriage. According to other information (from Augustine), the marriage would remain barren, or the woman could not bear living children and suffer miscarriages.

According to A. Akowan (Sandema-Longsa), courtship can continue under certain circumstances even if the applicant accidentally enters a house where a mat is being woven or shea butter is being prepared if the bride’s parents give the mat or part of the shea butter to the applicant as a gift. This is also seen as a sign of tremendous goodwill towards the suitor. Otherwise, the young man must cease all courtship efforts.

If there are no obstacles for the suitors, the group moves to the girl’s house and is received (possibly after a short greeting from the compound head in the kusung) in or in front of the girl’s mother’s room (dok). The girl caters for them, i.e. fetches them stools or chairs and offers them water and, sometimes, food. The applicant’s friends can accept water, but the applicant himself rejects the water ‘because the girl will always have to fetch water for him later as his wife’ (G. Achaw). The same applies to the food offered.

When the mother finally enters the scene, she asks the guests again if they want to drink water, even though she knows that {264} her daughter has already asked this question. The mother only complies with the request for an exchange of greetings after hesitations and evasions. When it is time to explain the reason for the visit, a young man may say something like they saw the daughter in the bush (wuuta); since it is assumed that she does not live in the bush, they would like to meet at her parents’ house. The mother says that is good, and a general conversation can begin, but the applicant does not participate. Whether the mother has anything against her daughter marrying the suitor, is asked of her directly. Still, she does not answer this question, instead promising to answer at the next visit.

Finally, the applicants ask permission to greet the other women of the house, and the group enters other parts of the compound. Often, the father and the other men of the house only receive greetings at the end.

On the first visit, the applicant does not need to offer any official gifts yet, but he can buy pito or other alcoholic drinks for the girl’s brothers or give some kola nuts to the father and the other older men. After the first house visit – but not necessarily on the same day – the compound heads inform the wena of the most important ancestors of the two houses concerned about the coming marriage. For this purpose, clear water from a calabash is poured over the wen stone, or the sacrificer lays his hand on the stones when he speaks to [endnote 13] the ancestors. Later, the ancestors can be informed about the matter’s progress and asked for assistance via a sacrifice [endnote 14].

The suitor tries to court the girl and her family in every possible way between the first and second home visits. The girl and her brothers’ wives are given money when they meet them at the market, the brothers are given pito, and the helpful neighbour is also invited. The girl herself is accompanied home by the applicant group after the market has closed, and on this occasion, one can also fix the time for further visits.

The applicant group can immediately move into the girl’s {26} parents’ house on the second visit. Again, they go to the mother’s dok; again the applicant refuses water; again, the mother objects to being greeted. This time, however, the mother is given a sum of money, which used to be 20–30 pesewas, but in 1974, it was about 2 cedis. When handing it over, some applicants say you can buy salt for this money. In Chuchuliga, as in Navrongo and Chana, the suitor gives the mother a guinea fowl and salt. The courted girl herself receives a gift of money of any amount.

The applicant is free to give small coins of money to the house’s children to endear himself to them. Other older women can also be freely given money. In Sandema, the men of the house do not usually receive money.

The suitor must give kola nuts (goora) to the girl’s father and to all the men of their house who are older than her father; he can give presents to the younger ones. For example, the applicant tells the father that he has just bought some kola nuts – since he still has some left, he wants to give them to the father. The father chews one nut and puts the others in the chickens’ water trough (kpa-chari, pl. kpa-chaa). Other men may also take nuts from this pot later if needed.

The house’s women are not supposed to spend their money on gifts before the wedding, as some suitors will ask for it back if the marriage does not occur. In this case, some men also buy new kola nuts to give back to the suitor. This reclaiming may harm the young man’s reputation, and there may be difficulties if he later courts another girl of the same lineage, as the parents of the first courted girl often inform the parents of the other girl about the reclaiming.

It occasionally happens that a girl calls all her suitors to her house on the same day. They are then taken to different rooms (diina), and the mother and daughter go from one room (dok) to another to greet their guests. It is said that the girl loves most the suitor with whom she stays the longest.

The third home visit is like the second but occurs without obligatory gifts in some parts of the Bulsa country. During this visit, the suitor asks the mother if he may take her daughter home {266} as a bride. The mother replies that she has nothing against it but that the decision lies solely with her daughter. As soon as the suitor can speak to the girl alone, he will also ask her when he can take her away, and she will again make excuses, such as that he has not yet visited her often enough. Then, it is time to ask friends of the girl’s house which suitor the girl prefers. A forcible abduction (yigrika) can be planned if one’s chances are not very good. Even if one gets the impression that one is ‘well in the running’, a forcible abduction may be the only means to prevent an abduction by another applicant.

d) Violent abductions [endnote 14a]

Violent abductions are often planned to occur at the end of a market day. The courting group can lure the girl to a house close to the market and belonging to relatives or friends. There, the courted girl is held until night falls so that the male group can safely take her to the applicant’s house. If other suitors, who usually do not let the girl out of their sight, have discovered the plans of their rival, there will be a quarrel, and often, the girl’s relatives will come and take her to her parents’ house. Recently, it is more common for the suitor group to offer the girl a ride home on a bicycle or, better yet, on a motorcycle. If the offer is accepted, one of the friends rides at great speed to the suitor’s section.

The following case is known to me from Kalijiisa-Yongsa:

The applicant gang from Yongsa kidnapped a young woman from Bilinsa-Tankunsa and brought her to their residence on a motorcycle. The girl’s father was furious about this abduction because his daughter was still wearing the undyed waist string (cf. Chapter I, 5; p. 44f.). The young men of the Tankunsa house were to bring her back, not knowing which house she was now in. When they came to the Yongsa house, they were allowed to search it. The girl, who agreed to everything {267}, was dressed in long trousers and a man’s smock (garuk, pl. gata) and put on a straw hat. My informant, G. Achaw, thus led the bride past her brothers and took her to a neighbouring house.

M. Arnheim reports from Gbedema: A woman married in Gbedema was abducted consecutively by men from Kanjaga, men from Fumbisi, and friends of her first husband from Gbedema. All three abductions took place over three months.

e) Abduction with the consent of the bride and the following marriage rituals

If no forcible abduction is planned or no opportunity arises, the suitor will urge the girl to tell him when he can take her home as a bride. She will eventually tell him where to meet at night. This meeting place is sometimes a spot haunted by evil spirits (kokta) or harbouring some other danger. Sometimes, the bride does not come to this place at all but only wants to test the courage of the suitor. As an excuse, she may say that her parents were watching her.

The applicant can ask her if she will give him a piece of clothing as a sign of her affection. The applicant can be sure of her honest intentions if she does so. If he feels betrayed, he can use the garment, or more precisely, the body dirt (daung) contained in the fabric, for a spell of harm against her out of disappointment.

Sometimes, the girl orders two or more applicant groups to different meeting points simultaneously, and only on the following day does one or the other group realise that they have lost the game if the girl has not preferred to stall all the groups again. To be kidnapped by the selected suitor, the bride frequently spends the night on the flat roof of a dok (as is typical on warm, dry evenings). The girl’s parents often know about the planned abduction or the day is even set in conversation with the girl’s parents. Nevertheless, the bride is usually taken away at night. I have been told that her mother sometimes accompanies the kidnapping party and spends the following night in the groom’s house, richly endowed. However, I have not encountered any concrete cases of this kind myself {268}.

In addition, it is common for suitors to come to the bride’s house in the afternoon and stay on the roof talking to the girl until late in the evening when all the other occupants have gone to bed. The house inhabitants usually know of the young men’s intentions, but they will pretend not to suspect anything if they have no objections to this marital union. At a later hour, the suitor and bride will climb over the wall and move to the groom’s house. The men’s group takes the bride into their middle while they make their way to their area without making a fuss or too much noise. If they are already singing the traditional wedding songs in a neighbouring section, you must reckon with the fact that the residents will try to take the bride away from the group.

As soon as the group has crossed the border into its own section, all the men in the group sing. The following song, in particular, is sung often in different variations:

A ku waali ba, a ku waali ba nong-liewa ku waali ba

A ku waali ba, a ku waali ba nong-liewa ku waali ba

D(u)erobai loa cheng chirika la – ooo –

Abiako biik laa cheng chirik la – ooo -.

They (the other applicant groups) have been punished (tormented, insulted) (twice),

The (other) lovers, they have been punished (repeated)

The men who walk by moonlight – ooo –

Abiako’s (name of the founder of the house) son is the one who walks in the moonlight. – ooo —

Another variation of the wedding song is also sung in Sandema:

Akatooknueri biik ga lie po ga tom we d(u)eroba.

D(u)erobai le cheng la.

Zula, zula.

The son of Akatooknueri goes to a girl and goes to report to the other friends (of the girl) that they (the successful group) are going (i.e., that they have kidnapped the girl).

Zula, zula (insult word against the other applicants) {269}.

Other songs that the young groom’s age group may sing strongly emphasise the ‘we’ feeling of the younger generation, who have not yet moved up to the position of compound owners. Some songs conspicuously lack courtesy and reverence for older people, which younger people usually show to the older generation despite many disagreements. These feelings are evident, for example, in the following two songs, which Ayarik (Wiaga-Tandem-Zuedem) says are sung almost exclusively when a bride is brought home:

Dandem jog yam, dandem jog yamoa, jog le po yiila.

Ba nyiam ya’eramiak, ba yaa yiti ka baano cheng, ate baano ga lerige lerige.

Ti sebla da ming te ba zag baandoari nag baano.

Old people have no sense; old people have no sense and no reason (yam and yiila are almost synonyms; yiila: dark Buli).

When they are sick, they get up and go to the diviner, and the diviner lies to them, lies to them.

If we (they?) had known, they would pick up the divination stick and beat the diviner.

Yeri-nyama ni ngaanga

Mi yaa la te ni ngaan’erami ka ni kan siag ya.

Mi yaa la te ngaang ge ni siaga.

Compound-owners, greetings to you [endnote 15].

I greet you, and you do not answer.

I greet you, and you do not answer.

Shortly before the wedding party arrives at the groom’s parents’ compound, its head informs his ancestors (wena) that a stranger (the bride) will stay in the house. Ayarik (Wiaga-Tandem-Zuedema) reports that at his wedding, his father, who was also yeri-nyono, poured a calabash of water over the bride’s head before she entered the house (Cf. a similar custom in Chapter VII, 4). This custom, however, exists only in {270} his house, not even in the other houses of Zuedema.

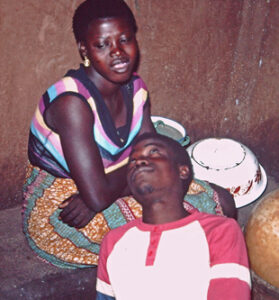

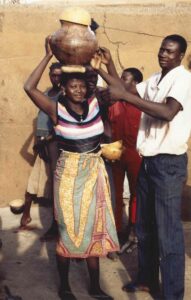

During the tour of a bride to the groom’s compound, which I attended myself, a bride was taken from Bilinsa to Kalijiisa. Apart from the woman, the group comprised seven young men of almost the same age. Most were from Kalijiisa, and some were the groom’s relatives, but I could also recognise one young man from Longsa. The groom held the bride by the wrist and pulled her behind him. Sometimes, he was relieved by another member of the group. Even from a distance, wuuliing cries could be heard from the groom’s house.

About 100 m before the house, the groom’s mother met us to accompany the group on the last part of their journey. We paused in front of the house, then climbed into the groom’s father’s living quarters. The latter could hardly hide his evident happiness; this was the first wife his two grown sons had brought into the house. He sat in front of a dok on which his weapons (bows, arrows, and skins of captured animals) were displayed and greeted the arrivals one after the other with a handshake but without official greeting phrases. The groom’s age group climbed onto a roof to continue singing there. The bride was seated on a mat in the middle of the courtyard. She spoke almost no words the whole evening. There was singing, dancing, eating, and drinking until about 3 a.m. [endnote 15a].

In Badomsa, I observed and documented part of the wedding celebrations [endnote 15b] in Abasitemi Yeri. The young son of the yeri-nyono had already taken his bride to his paternal compound, although the bride’s parents did not consent. They accused him of not having made enough visits.

During the ceremony, the bride was sitting in the room (dok) of one of the groom’s brothers, who was supposed to look after her. Later, several friends of the groom joined them. The bride was not as silent as I had experienced at two other weddings. She participated in all the offerings and brought the millet beer to the guests and household members in a large vessel.

What struck me was how the music was played.

The groom is beating a calabash bowl (drum substitute).

The groom sat on the courtyard floor, and a medium-sized calabash lay on his lower legs. He beat it with slightly bent sticks. A friend had placed a calabash on a cushion and beat it with his bare hands. The assumption that no real drums were at hand would be incorrect; several membrane drums were in the house. Instead, these calabash idiophones are prescribed. Apart from these, a neighbouring boy beat two calabash rattles (sin-yaala), and another man a vessel rattle in the shape of a closed calabash. The children were the main participants in dancing, but the compound head’s mother also danced with a little girl. The bride sat quietly in a corner. When I took some photos of the group, she made a point of including her in the photo.

On the left (in red) is the groom, in the middle the bride and on the right is a friend of the groom.

The bride and a classificatory brother of the husband

Dancing children

The bride carrying a vessel with millet beer

Evans Atuick mentions the activities of the compound head in his essay (2015: 95–96), from which the following quotation is taken:

After the singing had gone on for some time, the landlord [yeri-nyono] would come in with one or two fowls, a guinea fowl and some refreshment. He would ask the singers to stop singing and listen to him. He would then express his joy at having a new addition to his compound in the form of a wife and also for having the musicians with them to entertain and make merry with them. He would then pray to his forefathers for a fruitful and blissful marriage and also for the protection of all who have come to the compound to join them [in welcoming] the new bride. After saying this, he will just hit the fowl on the ground and throw it onto the [rooftop] for the yi’yiilisa (‘musicians’) while the guinea fowl is given to them to prepare something for the new bride to eat following her long and tiresome journey to the compound. He is also expected to give another fowl to the friends of his son who helped bring the new bride to the compound, but this is not obligatory. The singers must also be given some pito (da-moanung) or z’m-nyiam (‘millet/sorghum flour water’) when foreign drinks (e.g., akpeteshi) are not available to motivate and strengthen them to be able to perform well. After taking the refreshment, the singers would descend from the gbong and prepare their musical instruments (usually calabashes stocked with racks, metal buckets, etc.) to begin the jong-naka (making of entertaining and danceable calabash music). Meanwhile, the fowl for the singers would be de-feathered, and the feathers scattered all over the floor for the new bride to clean the next day as a sign of her readiness to take care of the house. Thereafter, there is drumming, singing, and dancing throughout the night until the morning when the landlord [yeri-nyono] shall come again to kill another fowl for them and bid the singers farewell.

Such celebrations usually extend over three days, or, better said, over three nights because, during the day, every guest goes about their work in their compound, returning to the wedding house in the evening for new celebrations.

The (classificatory) brothers do not only entertain the bride by providing her with delicacies (e.g. chicken meat). Often, their behaviour also takes on a very lewd manner (Inf. Sebastian Adanur, Sandema-Kalijiisa, 1979). They squeeze her breasts, pat her buttocks and in the past, they would even put her on the floor and check if she was already mature. With this behaviour, they also want to check whether she remains calm during all this or whether she insults the brothers. The husband is not jealous and withdraws from such actions. Educated or Christian Bulsa may reject the activities described.

Unlike many Southern peoples of Ghana, the Bulsa do not prescribe a particular day of the week or season for marriage, but a man should not bring a new bride home to his compound more than once a year.

Among the Bulsa, a young married woman (nipok-liak) is not forbidden from going out. After being shown her new home, she can return to the market. However, she is typically followed by many from her husband’s household since one can never be sure whether a gang of rejected applicants has not since plotted a violent kidnapping. On her first visit to the market, {271} the bride and all her female companions did not wear the traditional leaf dress (vaata), but a purple-coloured fibre tuft (also called vaata, cf. Fig. 15) at her front and back.

f) Older forms of marriage

While in 1974, the abduction of the bride without the knowledge and participation of the parents and sometimes against the will of the courted woman was the common form of bride acquisition, more regulated forms were common in the past.

After several suitors had paid their house calls, the parents asked the girl whom she wanted to marry. Although many parents might try to influence the decision, the final say lay with the daughter. The girl’s parents then notified the parents of the successful applicant, who came to the bride’s home on the morning of a specified day. The bride’s parents filled a large basket with food to be given to their daughter: for example, ground and unground millet, salt, dawa-dawa, and some slaughtered guinea fowl. A new sleeping mat was also provided. The groom’s parents, accompanied by some relatives, carried this dowry the same morning to their compound, where the bride would later live. All these things were considered the personal property of the woman. However, if she later married another man, she could not take the straw mat and the basket with her.

Before the evening came, the bride said goodbye to all the inhabitants of the house, who gave her small gifts (dried meat, dried fish, etc.) to take with her. She also said goodbye to her parents, crying to show that she was reluctant to leave them. In the evening of the same day, the girl, accompanied by a group of young relatives, went towards the groom’s house. Halfway, they met the groom, whom a group of friends accompanied, and together, they covered the last part of the way. The groom’s friends sang wedding songs when they reached their clan section {272}.

To the evolutionist reader, it may seem strange that here, the ‘bridal robbery’ appears chronologically after the ‘bride-acquisition contract’. Bride kidnapping is considered a modern degeneracy among the Bulsa and was made punishable, for example, by the Sandemnaab (the paramount chief of the Bulsa), especially if all home visits were omitted, and violent means were used.

Here, the impression must not be given that parents’ influence is lessened in all cases today. I know of several recent marriages where the initiative came from the groom’s and the bride’s parents. Mothers and fathers sometimes even choose a wife for their son living in southern Ghana and send her to his southern town of residence. Visits by the groom’s father to the courted girl’s home still occur today (information from R. Schott). Nevertheless, according to my observations and the statements of several informants, more and more young people seem to resist the interference of their parents in their courtship. Investigating whether the individualisation process has made marriage more or less stable would be worthwhile.

In recent years, marriages that come about through parents contacting in-laws are rare and seem to be resorted to when all other means of courtship have been unsuccessful. In 1988, I experienced such a situation with my assistant, Danlardy (or Dan). After several unsuccessful attempts to find a wife, he wrote to me that he would marry a daughter of the Kadema chief. However, she soon died in Sandema Hospital. Danlardy himself could not attend her transfer and funeral for emotional reasons. After an attempt to marry a doglie of his parental family also failed, he handed the matter to his mothers. A younger wife of his father’s eventually found a suitable girl in her birth section, Guuta, but she was still in school (class F3 of Sandema Continuation School) and was about 18 years old. On the morning of December 12, 1988, two of Danlardy’s stepmothers went to the girl’s compound. They took the bride first to Wiaga-Goansa, where Danlardy was living, and then to the traditional compound in Badomsa (See Chapter VII, 2n: Costs).

g) Marital sexual intercourse

The groom does not yet spend the first three nights after the bride comes to his house on the same sleeping mat, i.e. he does not yet have sexual intercourse with her. She sleeps with the groom’s classificatory brothers. Although there is a permissive relationship between them and the bride (see above), there is no sexual intercourse here either (Inf. by R. Schott). On the evening of the third day, the bride and groom bathe together in a corner of the compound without spectators. They use a calabash or a bathing clay pot, which must not be European or industrially made. This bath has a hygienic as well as ritual purpose. With the bath, all wrongful actions of their past life, especially {273} regarding sex (e.g. the wife’s premarital sexual intercourse) are washed away, and it would be a gross breach of custom if the husband later rebukes his wife for no longer being untouched. Previous marital ties of the woman are also supposed to be dissolved by this bath.

According to Sebastian Adanur (Sandema-Kalijiisa), this bath only occurs if the woman has previously had sexual intercourse with another man (for example, her former husband). The bath water is supposed to remove the power of the former husband, especially his influence, through a harmful medicine called song [endnote 15c].

My informant from Gbedema restricts the necessity of joint bathing even further: It only occurs in Gbedema if the woman was married to her new groom before, left him to live with another man, and then returned to him. Should the woman have engaged only in premarital sexual intercourse, the common bath is not performed in Gbedema.

Nipok-tiim

If the house has a nipok-tiim – a shrine consisting of two ceramic vessels and some accessories – the compound head (yeri-nyono) sacrifices a chicken and millet porridge (saab) to it. The bath described is then performed using water from the nipok-tiim vessels. Later, the bride and groom eat a medicine made from the charred roots of the nipok-tiim and shea butter. There do not seem to be any special rites preceding sexual intercourse with a girl who has never had intercourse. According to some informants (e.g. Ayarik from Tandem), the hymen is destroyed by the man’s penis (yoari); others claim that the husband does this carefully with a finger (e.g. Leander Amoak).

At least in the past, sexual intercourse was performed such that the woman lay on one side (usually the right), and the man attended to her from behind. As a justification for this position, I was told by G. Achaw that this was the usual sleeping position, wherein the woman lies in the middle of the mat on the right side, the man behind her, and possibly one or two younger children in front of the woman on the mat. In the sexual position described above, the parents would be less likely to attract the attention of the children present. Still, it is common to wait until the children have fallen asleep to initiate intercourse.

Pre-stimulation, e.g. rubbing the woman’s nipples, is known and used when, as G. Achaw says, the man ‘has romantic feelings’. However, the woman cannot demand that intercourse only starts when she is sexually excited. Touch and other manipulations, rather than visual cues, are typically used to stimulate the male partner for intercourse. Seeing a naked woman usually does not cause an erection; some men are even said to be incapable of sexual intercourse if they have previously seen a vagina (Inf. Gbedema).

According to my inquiries, coitus interruptus was known before the arrival of the Europeans but was rarely practised because, according to an old man, the feeling of pleasure suffers, and, in addition, people usually desire a fertile conception. More than one orgasm in a day is seldom desired, as the man loses part of his nying-yogsa-pagrem (health power) through sexual intercourse (cf. Chapter V, 1 p. 145). During sexual intercourse, the participants are in great danger. Insignificant incidents can have {274} a decisive effect here. G. Achaw gave the following information to R. Schott [endnote 16]:

There is a belief that when you are sleeping with your wife, and she happens to pass urine on the bed or whatever you are sleeping on, or a white ant bites any of you, the one who is bitten by the ant dies. When you are having sexual intercourse with your wife, and you cough, you shall get tuberculosis if you fail to say it out so that they may bring the medicine and perform the custom. The custom is performed in the room where you were sleeping; they close you, your wife, and the owner of the medicine inside the room. While the medicine is burning in the fire, you are to continue having sexual intercourse with your wife.

h) Akaayaali

For the validity of a marriage, the akayaali and the nansiung-lika rituals that occur later are very necessary.

The long name of the first mentioned ritual is ‘Akaayaali ale wa boro’ (‘Do not seek her [the bride]; she is [here with us]’). Usually, a few days after the abduction (though sometimes a few years pass), the groom sends an intermediary (san-yigma or sinyigmo) to the bride’s home to officially inform the in-laws that he has brought their daughter into his home as a bride. The intermediary is commonly from the groom’s section and is often related to the bride’s lineage through matrilineal descent or marriage. He not only an intermediary for the wedding of two people – but is also asked for in many other situations and rituals involving the married couple.

The akaayaali ritual is also described in the chapter on my assistant Danlardy’s payments for the wedding. The kayiita ritual (visiting brothers, Chapter VII, 2i; p. 276) can be considered part of akaayaali.

E. Atuick described these marriage rituals as follows:

A day or two after the akuwaaliba [taking the bride to the husband’s house], the young man (groom), in the company of a friend or two, must return to the compound of the bride to formally inform her father that they should stop looking for her because she is with them and that they are willing and ready to formalise their union. The young woman’s father would then tell them everything they needed to know about how to formalise the marriage. Having officially informed the landlord [yeri-nyono] and heard what is demanded from them, the young man and his friend(s) would bid him farewell and depart for home. Following their return to their compound, the brothers of the bride will follow up to the compound of their sister’s husband for the poi-deka (eating of the womb), the symbolic killing of an animal (either a dog, sheep or goat) for the brothers, who must eat everything with the exception of the waist, which must be handed over to the head of the girl’s family upon their return home. This actually confirms that her sister or daughter is actually married and that her brothers have been treated well by her husband and his family.

After the poi-deka, the family must recruit a san-yigma (‘the link-man’), usually a man whose mother or grandmother hails from the community of the bride or a nearby community, who performs the actual marriage rites on behalf of the groom. Once a san-yigma is found, they provide him with all the necessary items for the ‘akaayaali-ali-wa-boro’ so that he can proceed to the compound of the lady to initiate the rites. The items for this rite vary from place to place; in some areas, they collect goora, tabi (‘tobacco’) and money (kuboata pisinu, 50 pesewas) while in other places, they collect only goora and money (kuboata pisinu). The san-yigma, [upon arriving] to the area where the woman hails from, would usually find the san-yigdiak (a man who has relations with the place of origin of the groom, especially one whose mother hails from that area or an area closer to that area) to assist him performing the rites. The two of them then proceed to the bride’s paternal compound and hand over the required items after going through the customary greetings and formalities. The acceptance of these items virtually signifies that the woman’s family have accepted and formally given her hand in marriage to the man on whose behalf the san-yigma and san-yigdiak have come to greet and offer the items. It also means that another man cannot come to seek the lady’s hand in marriage since the family is now aware of her marriage to that particular man. Once the items have been accepted, the san-yigma must return to tell the groom and his family what transpired over there and what else is expected of them.

i) Visit of the bride’s brothers [endnote 17] {276}

In Buli, there are several terms for this ritual: kayiita, kayiita-deka (deka = to eat, to perform), biak-ngobika (eating the dog), or, more rarely (?), taa-ngang-sangka (= to follow the sister, sangi = to fix); E. Atuick uses the term poi-deka (eating the stomach).

The kayiita ritual can probably occur immediately after the akaayaali ritual (E. Atuick) or even a long time before, as I experienced in Danlardy’s house.

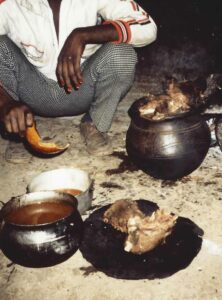

After the bride’s parents have been informed that a suitor has abducted their daughter, it is time for the bride’s brothers to visit the groom’s house. They stop outside the house and ask if their missing sister might be there {277}. They are asked by the head of the house to come in, but at first, they refuse, saying that they have no time. They would have to look for her in other compounds if their sister was not in this house. The house’s inhabitants can bring out a roasted chicken to make the brothers stay.

In the meantime, they discuss whether they can kill a dog for the brothers, as is the tradition, or slaughter a goat or a sheep as a substitute. The brothers are brought in to examine the live animal. One of them will now put his hand into the animal’s side and say that ‘a hole still needs to be stuffed’. The brothers will be given a live chicken to ‘plug the hole’ with. The brothers may ask for more chickens for other ‘holes’ in the animal until the head of the compound becomes angry (in mock anger). The boys may take all the donated chicks home with them.

Now, somebody slaughters the dog, and after preparing it, they entertain the brothers with its meat and TZ. After some time, the brothers may say they were not given all the meat. However, according to G. Achaw, this complaint is only a trap. If the homeowner also provides them with the roasted head of the dog, the brothers would immediately say that they had been bitten by the ‘owner of teeth’ (nyina nyono; a euphemism for dog), and the yeri-nynono would have to give them a sum of money as atonement.

The dog for sacrfice

The dog’s head

Preparing the dog’s meat

The millet porridge (TZ, Buli saab), which the house’s women bring in a calabash, also meets with the brothers’ criticism. They complain that the calabash wobbles. The husband or the head of the compound then puts a coin under the calabash, but now it wobbles to the other side. The brothers are often unsatisfied until coins support the calabash on all sides. In the past, the head of the house could also remedy the evil of the wobbling calabash by sending a little girl who had to hold the calabash in her hands while the brothers ate from it. When she was marriageable, this girl was given to one of the brothers as a wife. The brothers’ parents immediately decided which brother should have the girl when they returned to the family home.

Today, some young men who go to their brother-in-law’s house demand the dog (or goat or sheep) alive to {278} sell it at the market. Such a demand, however, is considered by many Bulsa to be a modern degeneracy.

The brothers usually go home with their gifts the following morning after being entertained for a whole night.

When Ayarik (Tandem-Zuedema) received the visit of his wife’s four brothers after his marriage, he gave them two bottles of akpeteshi [endnote 18] and a total of 2.10 cedis in addition to the gifts listed above. This amount of money, worth a guinea (21 shillings in the old currency), would not have changed even if more of the wife’s brothers had come. No dog was available in the house, so a goat was slaughtered. Ayarik’s wife also received some of its meat, while Ayarik’s father got the neck. The brothers took the goat’s head home.

In modern times, the kayiita custom seems to have changed slightly. According to M. Arnheim, only ‘greedy’ brothers of a bride would still perform it. The young men come from the bride’s house and other compounds in her lineage. Sometimes, they are even strangers who could have married the bride themselves.

R. Schott drew my attention to the fact that there may be reciprocity between the permissive behaviour of the bride’s brothers and the later, equally permissive behaviour of the son from this new marriage union towards the mother’s brothers and father. The right of claim of the bride’s brothers and later of the child towards his mother’s brothers is institutionalised in each case. For example, a ‘nephew’ can catch a chicken in his ‘uncle’s’ (MB) house with impunity and take it home. This permissive behaviour is often associated with a joking relationship (gbiera).

In Gbedema, I learnt that the ‘nephew’ can take liberties not only in his biological ‘uncle’s’ compound but in his mother’s whole section, only not to the same extent. Catching a sheep from a distantly related house would probably lead to trouble.

j) Visit of the bride’s mother {278}

A few months may pass before the groom, together with his intermediary (san-yigma) [endnote 19], visits his parents-in-law to invite his mother-in-law (nganub) to his house. This visit is called jo dok (enter the room). Before the young husband and the san-yigma enter the bride’s parents’ house, they consult on how much money the husband should give the mother-in-law during this visit. The amount of this money was about 5–20 cedis in 1974. The bride’s mother must accept any amount the san-yigma gives her. If there is any discrepancy, the san-yigma is reprimanded, not the spouse. If the bride’s biological mother has already died, another wife of the bride’s father receives the money.

After this visit (jo dok) and these payments, the mother-in-law {279} can visit the newly married husband in his house. She can bring her daughter some gifts (e.g. millet flour). If the daughter has not yet given birth to a child by this visit, the mother is entertained with one or two guinea fowls and TZ available to eat. Slaughtering a sheep or goat for her is only allowed if the daughter has already given birth. The bride’s mother can stay in her son-in-law’s house for several days and nights, and every day, she is served guinea fowls and TZ. In the evening, compounders and guests sing, play music, and dance as if the wedding just occurred.

When the bride’s mother indicates that she wants to go home, the compound’s men discuss what presents to give her. They will fetch a large busik basket [endnote 20] and possibly enlarge it by inserting sticks. First, all the male members of the house bring their gifts, including millet and sorghum (ground or unground), rice, slaughtered guinea fowl, dawa-dawa, salt, and money. The women of the house give presents for the upper part of the basket, such as dried meat (poultry or game), dawa-dawa, or salt. The head of the compound will slaughter a goat or sheep and give her some of the meat roasted and some raw in the animal’s skin. Often, more baskets must be brought in to hold all the offerings.

Some young married or unmarried women of the house – the visitor’s daughter may be among them – accompany the bride’s mother home and carry the gifts. When the group arrives at the bride’s parents’ house, everyone is served with prepared guinea fowl and TZ. They will then sing, dance and drink again, often until the early hours of the following morning.

The female companions sleep in the hosts’ house. They are, in turn, accompanied home by a corresponding group of men who have already attempted to meet them during the festivities of the preceding evening. These young women and their partners often maintain an exchange relationship of services and counter-services in return. The male partner may help the married woman on her farm, while she may provide him with a bride from her residential or natal section. The married woman’s lover, who courts her with the husband’s knowledge and consent {280} but is not entitled to any sexual practices, is called a pok-nong (friend of a wife) (cf. p. 261). If the woman is unmarried, a later marriage with her partner is possible.

A few days after the bride’s mother has left the husband’s house, the husband and his friends will pay a short visit to the house of the parents-in-law to inquire whether his mother-in-law has arrived home safely. Such a short return visit to inquire about the homecoming of an important guest is a common custom among the Bulsa (cf. Chapter V, 3 d; p. 172) and is called jianta (tiredness) since one also inquires after the tiredness (exhaustion) of someone returning home after a long walk.