CHAPTER IV

SCARIFICATIONS

1. SCARIFICATION AND RITES OF PASSAGE

Whether the cutting of Bulsa tribal marks can be classified as a rite of passage is highly questionable. By no means does a young person today, immediately after receiving the scars, step into a different status or age group. Nevertheless, these scars were at least once considered a prerequisite for respect as an adult; a refusal by children, if they can assert themselves at all, is undoubtedly associated with a loss of filial prestige.

Additionally, because these acts do not involve any sacrifices or divination, one may not think of a ritual act when speaking of Bulsa scarifications. However, even these simple operations are not wholly free of taboos, and it would be inappropriate to classify all scar-cutting in general as merely ‘cosmetic surgery’ or ‘medical intervention’. As explained below, the cutter of umbilical incisions is often not allowed to eat anything or rinse his mouth before the operation, implying a greater significance to the cutting.

A Bulsa teacher who successfully prevented his scarification told me that his father feared negative consequences for his son’s life after the refusal. However, when the worst did not occur with the eldest son, the father did not consider it necessary to have scars cut on the following children either – exemplifying a connection seen to exist between the scars and some life-determining forces of fate {118}.

2. TRIBAL MARKS (nyaga, sing. nyagi)

a) Forms and their local distribution

As one might infer from their label, these scars are intended to be distinguishing marks between the different tribes. In an essay on the Senufo, S. Siguino [endnote 1] argues that until the arrival of the Europeans, tribal scars served the purpose of identifying the male fighters on the battlefield. Women would later have taken up this practice out of pride and snobbery (…par orgueil ou par snobisme…). Some Bulsa informants also offer similar explanations for tribal scars. However, as C.H. Armitage pointed out in his work [endnote 2] on the tribal markings in the northern territories of the Gold Coast, and as can be seen exemplified in his numerous illustrations, these scars are only a flawed distinguishing feature between the tribes, since many are identical among different tribes. The diversity of tribal marks among the Bulsa, whose different variants also appear among other tribes, argues against the function of these scars as a militaristic tribal differentiation.

Sometimes, the clan section seems to be the basic unit for the shape of the tribal scars. My informant, Asugbe from Akanming Yeri (Wiaga-Sinyansa-Badomsa), reports that his father, the compound head , cut the scars of all his children himself between the ages of five months and one year in the way customary in Badomsa: two long scars on the left cheek and two on the right cheek (see Fig. 4, p. {119}). In the other sections of Wiaga, other scars would be cut (endnote 3).

Providing an accurate list of the scar forms of individual sections or section groups is difficult, as the type and number of scars are now very much at the discretion of the male individual or his father. A young man from Wiaga reported that his circumciser asked how many scars he wanted, and since my informant thought one scar was most beautiful, he was given only one incision. Others hold that a single scar on one’s cheek signifies cowardice – that is, the person concerned stopped the circumciser when he felt the first pain. It would thus be impossible to provide comprehensive documentation here. For almost all attributions of tribal scars to certain clan sections or localities, enough ‘exceptions’ could be found to complicate matters, especially in more recent times {120}.

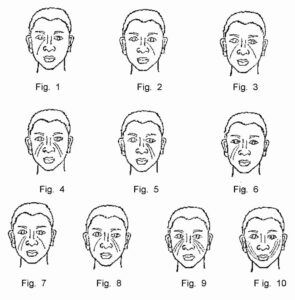

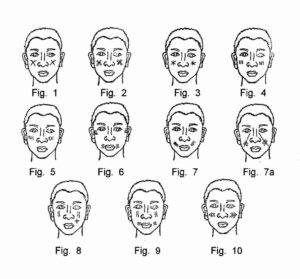

Among the Bulsa, the following arrangements of tribal scars occur:

Notes on the illustrations:

Fig. 1: Unknown in several localities; Wiaga: women of Tandem Zuedema and Tandem Kpalinsa wear them.

Fig. 2: Sandema: Abilyeri, Nyansa, Balansa (partly), Suarinsa, Kori; Gbedema: Jagsa; men of Siniensi; men of Tandem-Zuedema and Tandem-Kpalinsa.

Fig. 3: Sandema: Balansa (partly), Fiisa (formerly rare), men of Kalijiisa; women of Siniensi; Kadema: Bayansa (except women of Bayansa-Belesuk), Gadema, Buliba, Kpikpaluk, men of Zarik, Chansa, Yipala, Gomsa; Fumbisi (today); Kanjaga; Gbedema (for the most part); Uwasi (partly); Doninga (partly, not in Kong); Wiesi (partly).

Fig. 4: Sandema: women of Kalijiisa, men and women of Fiisa (partly), Balansa-Kambunsa; Kadema: women of Zarik, Chansa, Yipala, Gomsa, Bayansa-Belesuk; Uwasi (partly); Wiesi (partly); Doninga (partly); formerly in Fumbisi except Chiok; men and women of Wiaga-Badomsa (see above).

Fig. 5: Wiaga: men of Tandem Tankansa and Tandem Zamsa; Gbedema (partly)

Fig. 6: Wiaga: women of Tandem Tankansa and Tandem Zamsa.

Fig. 7: occurring in Chuchuliga (?), otherwise unknown.

Fig. 8: occurring in Gbedema.

Fig. 9: occurring in Gbedema; formerly also in Doninga (now very rare).

Fig. 10: Fumbisi: Chiok and Vayaasa. These scars (‘cat whiskers’) are considered typical of the Sisala.

The only section of Bulsaland with no tribal scars is allegedly Uwasi-Wasik, whose inhabitants are considered foreigners. Indeed, those without are said to be immigrant Dagomba.

If one examines the older ethnographic literature for statements about Bulsa tribal scars, one finds a note about Bulsa scarifications already in L. G. Binger’s writing [endnote 4] (1892, p. 56) {121}:

Plus au sud et à l’ouest de Oual-Oualé habite la fraction des Tiansi ou Boulsi, qui se tatouent de trois façons différentes. Ils offrent cela de singulier, c’est que deux des tatouages ont la particularité suivante, que je n’avais pas remarquée: les yeux eux-mêmes sont environnés de six petites entailles [endnote 5].

Further south and west of Oual-Oualé live the Tiansi or Boulsi, who tattoo themselves in three different ways. What is unusual about them is that two of the tattoos have the following peculiarity, which I had not noticed: the eyes themselves are surrounded by six small slits [endnote 5].

Later in Binger’s publication (p. 409), four illustrations with the corresponding Bulsa scars are depicted. Unfortunately, these early sources, as well as R.S. Rattray’s description of Kanjaga scars [endnote 6], are of limited value for a systematic study; neither the descriptions nor the illustrations indicate which scars are nyaga, wie-wie (ornamental scars) or i marks (incisions made after miscarriages and shortly after birth). This dilemma clearly shows that a phenomenological recording of tribal scars is of little utility. Instead, asking questions about the, purpose and names in the local language is imperative.

C. H. Armitage already distinguished between different scarifications according to their function in the work cited above. Unfortunately, however, there are only a few notes and sketches on Bulsa scars among the rich material. On p. 7, he points out the Bulsa, which he calls Kanjarga:

The Kanjarga natives do not appear to have any distinctive mark[s] of their own but use those of the Dagomba and Mamprusi indiscriminately, with other facial marks of adornment.

Yet on p. 23 of the same treatise, Armitage describes two illustrations (Plate XVI) with tribal scars of ‘Kanjarga natives’:

(Fig. B) A Kanjarga (Tchundemi) native. Three deep gashes – two parallel: one crossing them – on either cheek. The herringbone patterns between eyes and ears are placed on the first surviving child.

Tchundemi possibly means Chandem (i.e. Tandem). I {122} would like to assume that beyond the herringbone pattern, the parallel scars running transversely to the actual tribal marks (like Fig. 3 on p. {119} of this work) identify the wearer as a surviving child after a mother’s miscarriages. As a note to Fig. 9 of Figure Plate XVI, Armitage states:

A Kanjarga (Gbadamblisi) native. Three deep and wide cuts down either cheek from the eyebrows. Two heavy parallel cuts on the right cheek, two crossed on the left. These show that the wearer is not a full-blooded Kanjarga but is under the obligation to fight for the tribe…

Gbadamblisi probably means Gbedembilisi. The three sections mentioned, especially in Armitage’s illustration (Fig. 9), are notably reminiscent of the scars shown in my treatise under Fig. 10 (p. {129}). In both cases, they might have been applied to alien groups who immigrated to the tribe but have become Bulsa.

b) Execution of cutting scars

Although the age of cutting scars is unfixed, most Bulsa children receive their tribal scars between the ages of four and eight [endnote 7]. In no case may a younger child be cut if the father refuses to grant consent, as my informant G. Achaw reported from his childhood. He described how, when some children in a neighbouring house received their tribal marks, some relatives wanted to cut my informant, who was about 10–12 years old, together with the other boys. Achaw ran home crying. If they had actually cut him, there would have been a quarrel between the two houses, after which no more fire would have been exchanged. A short time later, a neighbour’s wife tried to cut nyaga scars on the still scarless boy as a joke. She applied the knife, and a dot-shaped scar still appears on Achaw’s face today. His father was irate about this, although the woman, who had never cut a scar before, said she had not seriously considered doing it.

Another informant without tribal scars reports that when the circumciser came, he fled to his house’s hot, flat roof, where no one suspected him to be {123}. Younger children’s motivation to avoid the operation is usually fears of the knife and pain; aesthetic, hygienic or cultural considerations, which are more likely with older children, rarely play a role at the age of scar circumcision. On the other hand, even the advocates of scarification can meerely cite traditionalist reasons: only with nyaga marks is someone a real Bulo; it has always been this way among the Bulsa; anyone who avoids these operations is a coward.

I know of a few cases where a pastoral group decided to have their tribal scars cut together because they were teased by other boys or girls who already had tribal scars. The majority suppressed concerns of individual group members, and it seemed daunting to exclude oneself from scarring as an individual, as the following quote from the life story of a young man from Sandema Tankunsa shows:

It was one day when one of our group members came and told us to go and have tribal marks. I didn’t like it because I feared the blood. I didn’t like to see blood flowing from me. So I told them to stop until the next season, but they all refused, and we went to the house where we [would] be given the marks. We [numbered] about eight boys. They started (with) the first boy, who had a straight and large mark on both cheeks. [After a] few seconds, [the] blood started flowing. I took my heels off to escape, but they chased me and brought me back. I was then the third boy, and they gave me the marks.

Augustine Akanbe, 30 years old in 1974 and from Sandema-Balansa, readily recalled when he often visited his mother’s brother in Kalijiisa to meet a girlfriend whom he hoped to marry one day:

… one day in the afternoon, we were sitting under a tree talking about the tribal marks, and there came a man from Chana. The man was the cutter of the tribal marks. Then the girl called him to come. She said to him: ‘Look, here is a boy {124} without the marks. His parents have been asking him to do the marks, and he would not agree because of fear.’

Then the man asked me: ‘Is it true?’ And I said: ‘No!’ The man then said to me: ‘Would you like to get it now?’ I was not going to agree, but because of the girl’s presence there, I thought: If I don’t do it, she may think that it is really true that I fear the pain of the cutting. So I answered: ‘Yes!’ So the man said to me: ‘Sit down and don’t fear. I will make it small, so you will not feel the pain’. So I sat down, and he began to cut me. One week after the cutting on my face, I said to the girl: ‘I will go to see my parents at Balansa and come back in two days’ time.’ She agreed that I should go ‘and come [back]’. I went to see my father. When he saw me with the marks, he was very happy. Also, my mother was happy, because they were asking me to cut the marks and I did not agree…

Unlike the examples reported here, tribal marks are usually cut on demand. The specialist, who often performs excisions or boy circumcisions as well, comes to the house of the man who has requested him; the neighbours, who also have children of appropriate ages, often take advantage of the opportunity and have their sons and daughters receive the scars at the same time. Cutting is done with the traditional knife (gebik, pl. gebsa), a smaller razor (poning) or a modern razor blade. If the circumciser does not have any of these implements, he can break a stone and incise the wounds with a splinter. The wound is then immediately treated with powdered charcoal and shea butter; it must not be washed for three days. The surgeon usually receives his payment in cash. Around 1960, the fee per child was about four pesewas {125}.

3. SCAR ORNAMENTATION FOR AESTHETIC OR PLAYFUL MOTIVES

For many Bulsa, the tribal scars (nyaga) comprise only an insignificant part of the scars they consciously acquire during their lifetimes. Most of their bodily scars will arise from purely aesthetic motives.

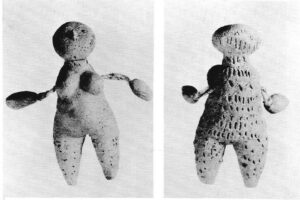

The shepherd boys’ self-made clay dolls (biik, mostly def. biika, also used as an indefinite form; pl. bisa), often roughly modelled in their extremities, generally show a pronounced level of scar ornamentation, exemplifying how almost all parts of the body can be provided with ornamental scars (wie-wie, sing. wiri, geometric ornament). Nevertheless, a biika is in my possession (cf. Figs. 21/22) whose entire back, legs and other parts are covered with many small vertical incisions, even while back and leg scars occur less frequently among living people than arm scars. Another biika (Fig. 24) bears vertical and horizontal scars under the neck and at the base of the breasts; these seem common among living people.

The illustration shows the front and back of one figure with numerous decorative scars. A girl made it.

An eight-year-old boy made this clay figure. Aside from the ornamental scars, it also bears tribal scars and an umbilical circumcision pattern.

A market visitor may notice the women’s numerous upper-arm scar ornaments, almost always resulting from many small incisions. I have encountered the following ornamental forms more frequently:

Upper-arm scars

While the wie-wie scars are evidently more common among women, they can also be worn by men. For example, my informant, Ayarik, has two rows of small vertical scars (similar to Fig. 1) on his right upper arm. His former {126} girlfriend cut them with a stone splinter when Ayarik was still in primary school. The girl then rubbed charcoal powder into the wound. The two rows of vertical incisions suited the girlfriend’s taste and had no symbolic meaning. You don’t cut these kinds of scars yourself – they can only be cut by a girl or a woman. However, a girl will only cut them for a boy if she is highly fond of him, and only if the boy feels the same for the girl will he permit her to do it. Some youths also rub a particular medicine into their incisions, which they believe increases their kpalem pagrem (a fighting power by which one can eliminate one’s rivals, cf. chapter. V,1, p. {145}). But even without medicine, scarification can bring prestige and success in courting women, signifying the wearer’s bravery.

If a boy with arm scars later courts another girlfriend, he can have more scars cut. However, this girlfriend will not continue the rows like her predecessor, as ‘the memories of the two girls must not be mixed in the mind’ (Ayarik). If possible, the second girlfriend will cut her scar-incisions on the other arm.

Girls can teach each other how to cut ornamental scars, which seems to be the typical case. Even if only one gender ever performs this service, payment can never be demanded.

The elongated scars described above, only applied by women or girls, must be distinguished from the round scars that shepherd boys apply to themselves or each other. For this purpose, they use the corrosive sap of a flower (tolum, pl. tolunta), which is applied in rows of dots on the upper arm. The following morning, the wetted skin area is swollen and leaves a circular scar of about 0.5 to 1.0 cm in diameter after healing. Other shepherds pinch pieces of skin from their upper arms with their fingernails to get similar scars. The herders’ parents do not object to these practices {127}.

4. UMBILICAL CIRCUMCISION (SIUK – MOBKA)

[endnote 8]

{127} At the end of September 1973, Ayarik, employed at the University of Cape Coast Hospital at the time, asked me if I would like to have a look at his three-month-old son’s umbilical circumcision. The baby had been suffering from pain in the umbilical region for a long while, and all the hospital’s remedies had not helped alleviate it.

The operation was scheduled for 6 am, as the circumciser was not allowed to eat or drink anything or rinse his mouth beforehand. He was a Bulo from Cape Coast’s Pedu area who was about 40 years old and not an English speaker. The operation was performed in the small anteroom of Ayarik’s one-room flat so that enough light could enter through the front door, which was left open. On a saucer was a black powder made by burning specific herbs and rubbing the ashes in a mortar. On another plate was a black ointment made from the same powder and shea butter [endnote 9].

When the circumcision began, the mother left the room – she could not stand watching the operation. Some neighbouring women and even small children watched from the door, however. The little boy sat on his father’s knees, naked save for his waist string with black beads. The father and I held his hands and legs.

The circumciser took a new razor blade and cut roughly ten incisions of about 5 cm in length radiating around the navel. The child smiled during the first incisions, but after, his face contorted into a quiet, whining cry. He did not seem in much pain yet; only a little blood came from the wounds. Then, the circumciser took the black powder and the black ointment and rubbed it into all the incisions with his hand so that the blood, powder and ointment mixed. After this, the child cried louder and urinated. The operation, which had lasted only a few minutes, was over. The mother returned and wanted to put her child on her breast, but the baby refused. The circumciser {128} received his payment of 60 pesewas (about 0.75 Euros) and returned to his village.

The wounds had healed entirely after a few weeks, and Ayarik claimed that the son’s pain, which was the reason for the operation, had not recurred.

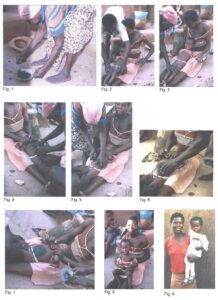

While observing and documenting gravediggers’ rituals outside the compound in Angaung Yeri (Wiaga-Sinyansa-Kubelinsa) on 20 March 1989, I was asked to attend an umbilical circumcision. A girl of about two years, who did not yet have a Buli name, was on her mother’s knees, sitting on the courtyard floor. The elderly female circumciser was grinding charred black medicine on a hoe blade. With a piece of charcoal, she drew the intended cuts on the girl’s belly. Similar to the Cape Coast marks, the black lines, about 5–10 cm long, ran radially from the navel across the abdomen (135). While the two women held the child, the circumciser used a razor blade to incise the pattern on the pre-drawn lines. Only a little blood came out. After the operation, the child stopped crying, only to wail louder when the black medicine was rubbed into the wounds. Immediately, without dressing the wounds, they put an open skirt on her and dressed her in her best clothes (for a photo!).

Notes on the photos:

Fig. 1: The cutter pulverises the charred medicine on a hoe blade.

Figs. 2 and 3: She has drawn the umbilical incisions with charcoal on the little girl’s belly.

Figs. 4 and 5: She uses a razor blade to score the girl’s skin along the pre-drawn charcoal lines.

Figs. 6 and 7: The cutter rubs the black medicine into the bloody cuts.

Figs. 8 and 9: Mother and daughter after the umbilical circumcision.

In other informants’ descriptions of navel cutting, I often heard that the cuts must be made with a quartz splitter (chising-chiin), but in both cases that I observed, a loose razor blade was used. All informants agreed that the cuts were not meant for body beautification but were performed for purely medical reasons after a child had fallen ill.

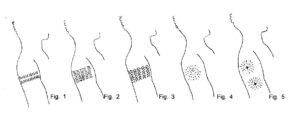

In the cases described above, the umbilical incisions were made in an irregular radiating arrangement (Fig. 1), but more regular shapes also occur among the Bulsa (Figs. 2 and 3).

Umbilical incisions

Allegedly, the different forms are only applied according to the tastes of the circumciser and the child’s parents.

In Sandema-Kalijiisa-Yongsa, Abiako Yeri (four compounds), navel-cutting is forbidden because the ancestors of these houses never circumcised their children’s navels. If the children of these houses have pain in the navel area, a neighbour comes and holds the child’s navel in a calabash with water and a specific medicine. This treatment is said to have the same healing effect as navel circumcision.

5. SCARIFICATIONS AFTER MISCARRIAGES

{128u} If a mother has frequent miscarriages (bia-kaasika or bia-kaasung, pl. bia-kaasuta) or her children die immediately after birth, incisions are made in both cheeks and sometimes in other parts of the body {129} of the next child born alive, shortly after birth. The forms of these incisions, their number, and where on the body they are cut vary so much locally – and often seem to differ substantially even within one section – that only a few of the many possibilities can be pointed out here. The following forms can occur as facial scars {130}:

Notes on the illustrations:

Fig. 1: My informants from Sandema and Kadema consider this scar arrangement the standard design for surviving male and female children to receive after experiencing prior miscarriages.

Fig. 2: I was assured that this arrangement of four scars each is only common among girls, as the number four corresponds to the female principle; I have only seen it among girls in Sandema (e.g. in Kalijiisa-Yongsa).

Fig. 3: As is to be expected, this form of three scars is only used on boys. However, an informant from Kadema claims that this arrangement and those of Figs. 4 and 5 are only cut as ornamental scars (wie-wie) in his section.

Figs. 4 and 5: These scars are cut, for example, on male (Fig. 4) and female (Fig. 5) children in parts of Wiaga.

Fig. 6: This arrangement, often in connection with other scars (see below), is particularly attributed to Wiesi (three scars: male child, four scars: female child),

Figs. 7 and 7a: Three (or two or four) oblique small scars may be given to a surviving child in Kanjaga, for example. In this position, the bia-kaasung scars are usually crossed by the tribal marks, as shown in Fig. 7a.

Figs. 8–10: I have not encountered the forms shown in Figs. 8–10 myself, but according to Edmund Acham and Awuudum (kambon-naab of Doninga-Doarinsa) they are said to be cut in Doninga as bia-kaasung scars among others.

The scars emanating from the corners of the mouth (Figs. 6, 7 and 9) can perhaps be viewed as influenced by the Sisala.

In addition to the incisions on the cheeks, other parts of the body may be scarred to indicate previous miscarriages; for example, small scars may also be applied to the temples, often three lines for boys and four for girls.

I heard that in Gbedema, the prevalent bia-kaasung scars have + and x shapes or more fantastical ones. If parents do not want their child’s face to be disfigured by scars, they put them on the feet or other less visible parts of the body.

A woman from the Wiaga chief’s house (Yisobsa) has four vertical, very thin incised scars on each cheek (like Fig. 5) and four small incisions on each temple, and {131} four scars on each upper arm and the front of the thighs. Other informants consider the custom of marking the upper arms and thighs with such scars typical of Wiesi.

All bia-kaasung scars have the same purpose: to deceive the evil spirit that harmed the children preceding them. This spirit cannot be classified as a known spirit or ghost (chichiruk or kikiruk, jadok, kok, etc.), so it is called ja-biok (evil thing, evil animal). This spirit often wants to harm a particular family by continuously taking children at birth, causing them to die. To deceive it, the infant is scarred immediately after birth so that the child no longer appears to belong to the family and receives the name of a slave or stranger (cf. chapter III, B, 3i, p. {105f.}).

It cannot be ruled out that there was once a connection between the chosen name and a particular scar form among the Bulsa, i.e. Amoak received the tribal scars of the Mossi, and Ayomo, the specific scars of slaves. However, my informants did not know anything about such connections, and comparisons of today’s bia-kaasung scars with the tribal scars of, for example, the Mossi, Haussa, and Kantussi have not led to any apparent result. In other West African ethnic groups, an awareness of this connection is sometimes more strongly preserved. For example, R. S. Rattray writes in his work Religion and Art in Ashanti (p. 65) about practices following miscarriages:

Such losses are looked upon as caused by malignant spiritual influences. To counteract, or rather, to deceive these, the parents resort to various devices. One of these is to suffix the name ‘donka’ (slave) to the natal day name … The same idea gives us ‘Moshi’ added to the ordinary name. The Moshi are the tribe in the north from whom the Ashanti formerly drew many slaves. The idea may be carried further, for the infant may actually be given the tribal markings of one of the slave classes (the Ashanti ordinarily never tattoo) … {132}

The similarity to the practices and motivations of the Bulsa is astonishing, especially since the culture of the Ashanti is not so closely related to that of the Bulsa in other respects and is assigned to a different cultural circle by adherents of the cultural circle theory [endnote 10].

In northern Ghana, the awareness of connections between foreign tribal names and scars is sometimes well-preserved among other ethnic groups. E. Haaf [endnote 11] notes this in his work on the Kusasi:

…Such a child is called Ayarega [endnote 12], slave, and is even given the mark of a slave, consisting of two fine arched facial cuts. To such consistently performed deception, even the spirits succumb…

Kusasi student from Legon also reports that a child is given to a stranger for a short time after a long period of childlessness and receives the stranger’s tribal scars (as bia-kaasung scars) in his house.

6. AKAN SCARS

Although tribal marks in northern Ghana can hardly be used to distinguish tribes, in a southern town, people from the north of the country can easily be recognised by their long scars that run from the nose’s root and across the cheek. The southern tribes only cut small, 1–2 cm long, mostly horizontal incisions on one cheek, initially only for medical reasons. These Akan scars have recently become popular among young Bulsa. In the past, young people who were born in the South or grew up there adopted these scars, introducing them to the north as a visible sign of their ‘Kumasi stay’. Today, as there is someone in almost every larger town who knows how to cut these scars, it is already possible to have such Akan scars cut in Bulsaland. These cutters, who have lived in the South for a long time themselves, usually do not cut Bulsa tribal marks and cannot perform circumcisions of the sexual organs. An elderly man from Kalijiisa-Yongsa, who usually lives in Kumasi, cuts Akan scars in Yongsa for 20 pesewas (1974 about DM 0.50) per person during his holiday {133}. In a holiday period of a few weeks, he is said to have brought it to almost 20 cedis – that is, he cut nearly 100 Akan scars.

The primary motive of young Bulsa to receive these non-tribal scars is to obtain a fashionable aesthetic. With them, they can flaunt the bearer’s southern experience. In addition, because a particular medicine is rubbed into the fresh incisions, a magical–medical reason supports such scarring. This is why they are often cut on small children a few months after birth – in one case, immediately after the segrika.

In Achaw Yeri in Kalijiisa, a girl, barely four months old, underwent such an incision. Some days afterwards, the young mother had to rub a black powder into her daughter’s wound after each of her child’s baths until the incision had healed. Judging by the child’s reaction, this rubbing must be quite painful.

A young man from Sandema-Longsa, born in Sekondi, tells of how he came to have his Akan scars as part of his life story:

At that time, in the twin city of Sekondi-Takoradi, there was a certain type of disease among infants called Amuna in the Akan language. This disease attacked the joints so that you felt it like a shock from electricity. My mum was carrying me on her back on hawking business when I collapsed. An onlooker told [my mum] to tie the cloth well for I would fall. My mum put away her wares and set about tying the cloth when she saw I was stiff and breathless. It was five hours in hell for such a young woman who had [her first child]. She started wailing and sprawling on the ground, calling names of our ancestors to come to her aid. A middle-aged Fanti woman told her: ‘Mammy, why do you weep when your child is not dead? I shall endeavour to help you. Get up, collect your wares and follow me.’ Thus this woman took me into her arms and carried me to a house near the shore. Pepper, ginger, and some leaves were mixed and squeezed into my nose and ears. After an hour {134}, I came around crying. I was fed on the breast, and my mum went on her knees, thanking the old lady.

The second episode of this same disease attacked me on Easter Day when my Dad and Mum were having their supper. The whole house was thrown into confusion, but this time a remedy stronger than the first was necessary. I was rushed to an old lady who gave me the same treatment as the middle-aged woman, but this time she had to give me a cut on my left cheek. Black powder was rubbed into it. Thus I came back to life…

Many Akans believe that a specific bird causes these convulsions in small children. However, these are probably symptoms of brain malaria that occur primarily in children. According to E. Haaf [endnote 13], the Kusasi believe that the convulsions of brain malaria ‘are caused by a bird, Nimbia, very probably Caprimulgus nigriscapularis (black-shouldered nightjar).’ The Bulsa also believe that the cramps are caused by a bird (nuim), called nkonya (Akan?), so they also call the disease nuim. The medicine, an oily substance sometimes called nuim, is obtained by charring this bird’s bones and flesh, then mixing it with shea butter.

7. EXCURSUS: TATTOOING

For the Bulsa, tattoos (chaka-chaka, or ngmarisika v.n.) are seen as a new kind of body adornment that did not exist in the past. Nevertheless, unlike the recently introduced male circumcisions, parents usually do not object when their children receive tattoos. Even older people are sometimes seen with tattoos adorning their bodies, and I have heard of parents having their children tattooed at an age when they could not yet make an independent decision. This positive attitude towards a practice alien to the old traditions can be explained by the fact that tattoos have remarkable similarities to wie-wie scars in their application technique and function as body ornaments {135}.

According to literature surveys by S. Wohlrab et al. (2007: 1346), tattoos in ‘primitive cultures’ are considered status symbols. They serve the purpose of ‘social stigmatisation’ and provide information about the wearer’s clan affiliation. These functions do not apply to the Bulsa people. Instead, they serve to beautify the body and are intended to attract the attention of others (cf. Wohlrab 2007: 1343), which is particularly important in courting efforts. Tattoos also testify that the wearer can endure a certain amount of pain.

Even if some of the tattoos today were acquired in the South or abroad (e.g. by African British army soldiers), there is now the possibility of receiving tattoos in Bulsaland. For example, at the Sandema market, a tattooist had a small stall displaying his patterns: stylised scorpions and lizards, wristwatches, geometric  patterns and ornaments. Names of boyfriends or girlfriends in large block letters are also popular. In one well-known case, a married woman had the name of her (pok-) nong [endnote 14] tattooed on her chest. However, one of the most common tattooing patterns seen on people consists of simple blue vertical lines under both eyes. According to information from Gbedema, the pattern shown is one of the most frequently used.

patterns and ornaments. Names of boyfriends or girlfriends in large block letters are also popular. In one well-known case, a married woman had the name of her (pok-) nong [endnote 14] tattooed on her chest. However, one of the most common tattooing patterns seen on people consists of simple blue vertical lines under both eyes. According to information from Gbedema, the pattern shown is one of the most frequently used.

This tattoo has a purely aesthetic purpose and is free of magical or medicinal secondary functions. In the other forms, a magical meaning may be associated with the aesthetic one, e.g. if one hears half-jokingly that a tattooed scorpion protects against scorpion bites.

The tattoos themselves are done, for example, in the open air of the market under the eyes of many curious spectators [endnote 15]. The tattooist draws the pattern, e.g. a scorpion, with black liquid ink on the intended body part [endnote 16]. Then, with a small knife, he stabs a few millimetres deep into the inked areas of the skin so that the colour can flow immediately into the incisions. Finally, the paint is rubbed into the many tiny cuts and then rubbed off. Blood is never seen. Women, in particular, cannot entirely suppress their pain during this procedure, expressions of which are accompanied by laughter from the onlookers. In 1974, 30 pesewas were paid for this procedure, collected before the tattooing commenced because someone once ran away before it was entirely done.

More recently, tattoos are often imitated by ballpoint pen drawings, especially on children and shepherds {136}.

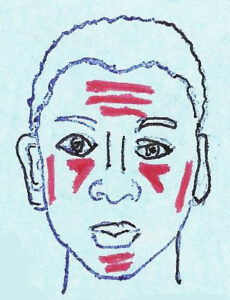

8. EXCURSUS: BODY PAINTING

While tattoos near-exclusively belong to the secular sphere of life, body painting with earthy colours probably unfailingly into the ritual sphere. The latter plays a crucial role in funeral celebrations, for example. Relatives of the deceased paint (lagsi daluk) finger-wide lines on their faces in a red earthen colour; these lines strongly resemble the tribal scars. Close relatives, especially children of the deceased, also have their bodies painted in this red colour. The meaning and function of these paintings will be examined in more detail in the chapter ‘Death, Burial and Funeral Celebration of the Dead’.

Body painting also plays a role in areas of life beyond ritual. Ayarik from Tandem once played in a pond as a child, and an older boy on the pond’s bank tried to hit the other children diving underwater with a pointed stick. When Ayarik surfaced, the older boy threw the ‘spear’ into his neck, and the seriously injured Ayarik was taken to Navrongo Hospital. Before that, however, they took red earth colour and painted patterns on his left cheek like tribal scars. The same procedure was done on his father, mother and siblings.

If someone in a hunting party is accidentally shot by his hunting companion, the injured party is given red face paint while still in the bush. When they get home, their parents and siblings will also paint a red line on their left cheek (Inf. Ayarik).

Colours in body painting can also signify protection. Following sacrifices to certain earth shrines (e.g. if witchcraft is suspected), some earth from this shrine is eaten by some or all participants. Moreover, the initiators of the sacrifice may be painted with earth from the tanggbain on certain parts of their bodies at their request or on the orders of a diviner (baano). For the tanggbain Pung Muning in Wiaga-Badomsa, I have described the ritual of painting (lagsika) in Kröger 2017: 21:

The members of the donor group enter the inner stone circle [of the tanggbain] one by one, and the sacrificer paints (lagsi) red lines or patches of tanggbain-earth on their bodies, foreheads, chests, both elbows, the back, the knees and sometimes on the back of each foot as well. The [earthen] colour should remain on the body at least until the evening bath. It is a blessing for a painted person to also spend the following night with the body colour on…

Body-painting at Pung Muning

After another tanggbain sacrifice to Pung Muning, I saw that a young man, the only one in his donor group, refused the paint because he feared he would be exposed to particular punishments by the tanggbain.

In Wiaga-Longsa, the teng-nyono [earth-priest] forbade me to wash the paintwork in a river after I had been painted with the black mud (bakta, sing. bauk) of the river tanggbain Kunjiin. In Longsa, the mud had been applied only to my chest, back and forehead.

The Daluk-tanggbain in Wiaga-Longsa provides red laterite earth for users from large parts of Bulsaland, who use it for body painting, the red coating (engobe) of ceramic vessels (before firing) and painting drums. In all cases, the Daluk-tanggbain is said to have a protective function due to its red earth.

9. STUDENTS’ ATTITUDES TOWARDS SCARIFICATION AND TATTOOING

Some influences of traditional society and religion on young people can be more or less reversed {137} by them after schooling has mentally and spiritually shaped them. A Bulsa name can be replaced by a Christian one, and a wen-bogluk (see below) can be destroyed. In the case of other influences and rites, the adolescent can decide independently under which rituals to enter a new phase of life, as is the case with marriage, for example.

The tribal marks are usually cut on children at an age when they have not clearly decided between, on the one hand, a school career and a life in southern Ghana or, on the other, life in a Bulsa compound. Since the consequences of scarification cannot be removed later, the remorse and shame of having large Bulsa tribal scars are weighty among some students. Two fourth-grade students at a Sandema Middle School with above-average academic performance, one wanting to attend secondary school and the other wanting to become a nurse, openly expressed their disgust at the tribal marks and tattoos under their eyes. Their parents had caused these marks, allegedly without any purpose, just for their amusement. When the two girls come to the South, they will not only buy wigs and soap that make their facial skin lighter but also have their tattoos and scars removed as much as possible – they claim that there are remedies for this in the South.

The aversion to northern tribal scars among Bulsa students may be strongly motivated by the knowledge that Europeans and Akans see the large scars as ugly and barbaric. One young man, for instance, said he would be ashamed to go to Europe with large tribal scars. He recounted that one of his friends with long, wide tribal scars was asked in Europe if a lion in Africa had attacked him.

Nevertheless, some Bulsa in southern Ghana again consider their tribal scars as a genuine tribal emblem (‘… because I want to make people know that I am a Bulsa’), even if the Bulsa cannot be distinguished from other northern tribes by their tribal scars. Others, primarily Bulsa men in the South, do not reject ‘tribal marks’ in principle, but {138} only oppose scars that are too long or too wide. A young man from Kadema recalls in his life story:

At that time, I understood a tribal mark as a decoration of the face. So I was happy to have it. Anyway, since it is a tribal thing, it is not bad to have it, only the marks are too long and big, [so] I don’t like them.

Conforming with the last statement, there is a marked aversion to having double scars on both cheeks. Moreover, illiterate people often prefer to have only one scar cut on each cheek or to give this simplified form to their children, even if the double form was common in their section. The bearers of this one-sided scarring must put up with the reproach of cowardice.

The southern peoples of Ghana consider the long scars of the northern tribes a sign of backwardness, and they are commonly regarded as ugly. In a kitschy romance novel [endnote 17] in three parts – which, according to my survey (1973–74), was one of the most popular leisure readings of middle-school Bulsa students – a young Akan, after being accused of murder, tries to hide under a false name in northern Ghana among the Mamprusi; at his request, he has multi-tribal marks cut so that he can better remain anonymous. As the following examples show, these marks are almost always given pejorative attributes by the author, E. K. Mickson, a journalist for the Ghana Pictorial magazine [endnote 18]:

(p. 23) But, perhaps, it was because he felt ashamed that somebody who knew him previously might now see him with humiliating tribal marks.

(p. 35) He was a Northerner with wild tribal marks…

(p. 67) Otherwise, how would I, a pure Akan, have come by these unrelated, strange and humiliating tribal marks…?’

(S. 69) … living in disguise under these indelible tribal marks…

Although many students and graduates reject northern scars – especially if they have contacts with the South – there is {139} nevertheless a reason that can make them supporters of Bulsa tribal scars. My assistant, G. Achaw, a nurse in Cape Coast who had always been a fierce opponent of excision, circumcision and umbilical incisions and had successfully opposed tribal marks being cut on him as a young boy (see above), surprisingly admitted that he would have his children cut with Bulsa tribal marks shortly after birth if he married an Akan woman. Here, the tribal mark becomes a tool in the struggle for children between a man from a patrilineal society and a woman from a matrilineal society. Like many other Northerners, Achaw fears that if there is a dispute, the woman may run away with the children to incorporate them into her lineage, to which the matrilineal Akan people believe they belong. Here, tribal marks are given a function again, as they may have had long ago: to document membership in a particular tribe and at least render it more difficult for a person to alienate one’s son from their tribe.

Students’ and graduates’ attitudes towards Bulsa facial scars cannot be easily transferred to other scars. Smaller southern facial scars are found to be beautiful and modern. Navel cuts, rarely visible to the public when students are fully clothed, often have a purely medical explanation. I have seen them in Sandema on pupils who otherwise bore no scars on their faces. The navel circumcision in Ayarik’s home described above was preceded by an agitated discussion between Ayarik and his colleague and the assistant I mentioned above who works at Cape Coast Hospital, G. Achaw. A trained nurse, he believed that the whole affair was just superstition: the cuts were only made so that the evil spirit tormenting the child would not recognise its victim. He argued that tetanus infection could occur by rubbing this black medicine into the wound. Ayarik, however, could not be swayed. He also cited medical reasons: experience had shown him that cuts helped much better than hospital medicine, which often only had a short-term effect {140}.

ENDNOTES

CHAPTER 4: SCARIFICATIONS

1 Siguino 1953: 22f.

2 Armitage 1924.

3 Notably, Akanming belongs to a section in Siniensi; he is related to Badomsa, its residential section, only by matrilineal ties.

4 Binger, vol. 2, 1892.

5 I am not aware of such cuts as tribal scars. Arguably, they can function as ‘beauty marks’ at will.

6 Rattray 1969: 14f.

7 Information after 1974 has shown that umbilical circumcisions can be performed much earlier (from the fifth month of life).

8 Although navel circumcisions are usually performed during a specific stage – the first months or years of life – they can hardly be called rites of passage. Their primary purpose is to heal an illness. They are noted here to give the scarification chapter a certain completeness {358}.

9 According to E. Haaf (1967: 167), such an ointment among the Kusase (Kusasi) consists of the ashes, powdered leaves, and roots of Calotropis procera (Asclepiadaceae), which are processed with shea butter. The cuts are supposed to provide an outlet for evil.

10 H. Baumann assigns, for example, the Ashanti to the East Atlantic and the Bulsa (Kandiaga, Builsa) to the Volta cultural circle. Cf. H. Baumann, R. Thurnwald and D. Westermann, 1940: 289 ff., 300 ff., 344.

11 Haaf 1967: 88f.

12 Ayarega probably corresponds to the Buli name Ayarik (‘Kantussi slave’).

13 Haaf 1967: 146.

14 A pok-nong relationship (pok = wife, nong = lover) can exist between a married woman and a man who is not related to her. The husband knows about this platonic relationship and agrees to it. Cf. Kröger 1980.

15 I. Heermann also confirms this for Wiaga (1981: 225).

16 The ink is an imported product and has no medical function.

17 E. K. Mickson, When the Heart Decides (Accra-Tema, n.d.); Who Killed Lucy? (Accra-Tema, n.d.); Now I Know (Accra-Tema, n.d.).

18 All quotes from Part 3: Now I Know.

- Title, Contents and Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter I: Pregnancy

- Chapter II: Birth

- Chapter III: The Guardian Spirit, Naming and Names

- Chapter IV: Scarifications

- Chapter V: Wen Rites

- Chapter VI: Excision and Circumcision

- Chapter VII: Courting and Marriage

- Chapter VIII: Death and Burial

- Chapter VIII (contd.): Funeral Celebrations

- Conclusion

- Appendix