Franz Kröger

The Koma and Bulsa (Builsa) of Northern Ghana

Every Bulsa will probably have noticed that Buli is very closely related to some neighbouring languages, for example those of Frafra (Nankanse), Tallensi, Mamprusi, Dagomba, Mossi and others and less so to other languages – even immediate neighbours – like Kasem and Sisala, for example. Linguists have tried to give names to these kinship relations by naming the first group mentioned here as the Mole-Dagbane (later Oti-Volta) languages and the second as the Grunchi (Gurunsi) languages.

Every Bulsa will probably have noticed that Buli is very closely related to some neighbouring languages, for example those of Frafra (Nankanse), Tallensi, Mamprusi, Dagomba, Mossi and others and less so to other languages – even immediate neighbours – like Kasem and Sisala, for example. Linguists have tried to give names to these kinship relations by naming the first group mentioned here as the Mole-Dagbane (later Oti-Volta) languages and the second as the Grunchi (Gurunsi) languages.

Finally, it was recognized that all these languages belong to a large language family in West Africa, which Gottlob Krause (1850-1938) called the “Gur languages” (endnote 1).

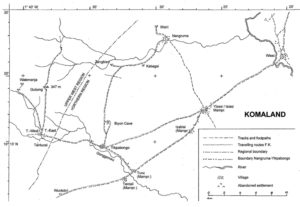

The Bulsa would certainly like to know which other Gur language Buli is most closely related to, i.e. which other language is most easily learned by the Bulsa. The linguists are quite unanimous that this is “Konni”, the language of the Koma in the southwest of the Bulsa area. Nevertheless, the Koma are not so well-known among the Bulsa as are other groups like the Kasena and Frafra. This may be, because the Koma area is very inaccessible, especially in the rainy season, and is therefore referred to as “overseas” by neighbouring groups.

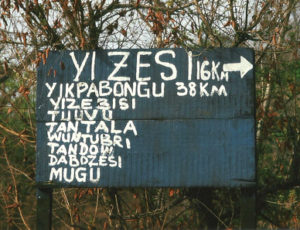

Before my first contacts with the Koma, some Bulsa told me that in the Koma villages of Yikpabongo, Nangruma, Tantuosi, Wuntubri, etc., Buli is spoken. Although this assumption is wrong, it is understandable because, for the Koma, besides the Mamprusi villages of Tantali and Kundugu, Fumbisi is the most important local market, and most Koma visitors speak more or less good Buli.

The two languages discussed here are linguistically very related. Bulsa visitors to Komaland will immediately notice that many words that end on different consonants in Buli (e.g. -k, -m, -n, -i) end on -ng [ŋ] in Konni. For example:

English Konni Buli

English milk, Konni biisiŋ, Buli biisim

English fibre, Konni boŋ, Buli bog

English pestle, Konnie buluŋ, Buli buluk

English tribe, Konni buuriŋ, Buli buuri

English star, Konni chiŋmariŋ, Buli chingmarik

English pito, Konni daaŋ, Buli daam

English day, Konni daaŋ, Buli dai

English bush pig, Konni duaŋ, Buli duok

English to performan a sp. ritual, Konni gaasiŋ, Buli gaasi

English cloth, Konni gariŋ, Buli garuk

English long gown, Konni gatiaŋ, Buli gatiak

English hole, Konni goliŋ, Buli goluk

English new, Konni haaliŋ, Buli paalik (endnote 2)

English debt, Konni hamiŋ, Buli pami

English shell, Konni haŋ, Buli pauk

English thing, Konni jaaŋ, Buli jaab

English sp. shrine, Konni jadoŋ, Buli jadok

English place, Konni jigiŋ, Buli jigi

English sp. basket, Konni jikɔriŋ, Buli yikoari

English sp. horn, Konni kantaŋ, Buli kantain

English read (v.), Konni kariŋ, Buli karim

English bone, Konni kobiŋ, Buli kobi

English death, funeral, Konni kuŋ, Buli kum / kuub

English hoe, Konni kuuŋ kui, Buli kurik

English occiput, Konni kpaaŋ, Buli kpai

English fowl, Konni kpiaŋ, Buli kpiak

English dead, Konni kpiiŋ, Buli kpiuk

English taste (v.), Konni laŋ, Buli lam

English string, Konni miiŋ, Buli miik

English bad luck, Konni naabiaŋ, Buli nanbiak

English grinding stone, Konni niiŋ, Buli niri

English eye, Konni niŋ, Buli num, pl. nina

English mouth, Konni nuaŋ, Buli noai

English grind , Konni, nuŋ, Buli num

English water, Konni nyaaŋ, Buli nyiam

English tooth, Konni nyiŋ, Buli nyin

English leave, Konni nyiŋ, Buli nyini

English yam, Konni nyuŋ, Buli nyuri

English wall, Konni paŋ, Buli parik

English guardian, Konni, sigiŋ, Buli segi

English groundnut, Konni siŋkpaaŋ, Buli sungkpaam

English plunge basket, Konni sugiŋ, Buli sogi

English plaster (v.), Konni taariŋ, Buli taari

English talking drum, Konni tampaŋ, Buli sampain

English tree, Konni tiiŋ, Buli tiib

English medicine, Konni tiiŋ, Buli tiim

English bean, Konni tuŋ, Buli tuni

English work (v.), Konni tuŋ, Buli tom

English heat, Konni tuiliŋ, Buli tuilim

English hole, Konni voriŋ, Buli voain, vorub

English antelope, sp., Konni waliŋ, Buli walik

English sweat (n.), Konni waliŋ, Buli wulim

English understand (v.), Konni wuŋ, Buli wom

English gall, Konni yaaŋ, Buli yaam

English clay, Konni yaŋ, Buli yak

English white, Konni yialiŋ, yieliŋ, Buli pielik, pieluk

English be blind, Konni yiiŋ, Buli yi

English arrow, Konni yiiŋ, Buli pein

English duiker (antelope), Konni yisiŋ, Buli yisik

English night, Konni yuŋ, Buli yok

English monitor lizard, Konni yuoŋ, Buli yuk

English blood, Konni ziŋ, Buli ziim

English flour, Konni zuŋ, Buli zom

Similarly to the Bulsa, the North-Konni dialect (like the one spoken in Nangruma, for example) does not have a spoken initial h-phoneme, whereas this is the case with the South-Koma dialect (e.g. spoken in Yikpabongo).

In view of the great linguistic similarity between Konni and Buli, it is at first sight surprising that other cultural elements of the two ethnic groups do not share any more similarities than with, for example, the Frafra (Nankanse) and Kasena groups.

Constructing the suging figure

In the following only a few selected comparisons between some cultural elements of the Bulsa and Koma can be made. With regard to religion and ritual life, only funeral celebrations and ritual and festive elements connected with ancestral sacrifices will be dealt with here. A Bulsa visitor to Koma funeral ceremonies will find some striking differences. In order to clearly represent the dead person in the celebrations and in a way accessible to ritual acts, there are two means in Bulsa funerals:

1. by the death mat of the deceased, which is placed at the granary of the compound. Here it is welcomed by arriving guests and later burned before the dead person enters the ancestral realm.

2. by the deceased’s daughter-in-law who, wearing his clothes, represents the dead dramatically. She is addressed by the name of the dead man and plays scenes from his life in small, impromptu dramatic performances.

The Koma are also familiar with the representation of the deceased by a woman in the clothes of the dead. However, she plays no major role in the performance of the ritual events.

The suging figure

Grandchildren trying to steal the suging

Rubbish and leaves thrown onto the canopy by the grandschildren

At the focus of the Koma funeral ceremonies is an inanimate figure wearing the clothes of the deceased. The inner framework of this effigy consists of a plunge basket (Konni: suging, Buli: sogi) and a short pestle(K: bulung, B: buluk) representing the head and neck of the figure. As in the personal imitation of the dead among the Bulsa, a humorous element enters into the ritual sequence of a funeral among the Koma. Here it is not the imitative scenes but rather the grandchildren of the deceased who provoke laughter and sometimes even feigned anger on the part of some of the gathered people. The grandchildren were already practising a joking relationship (jaaling, verb: karisi) with their grandfather during his lifetime, and this relationship continues to an increased degree at the funeral ceremony (cf. Kröger and Baluri 2010: 405-410). For example, when visitors place coins and bank notes on the canopy above the figure, the grandchildren throw rubbish or leaves on the cloth. To the dismay of the organizers, they even try to steal (kidnap) the figure and disappear with it.

Detailed investigations analyzing to what degree similar figures are included in the ritual events of other ethnic groups in northern Ghana would be revealing.

A second ritual celebration which is connected with the offering of sacrifices to the ancestors and other shrines should be included in our comparison of the two ethnic groups. Among the Bulsa, this celebration, called fiok or fanoai bogluta, always takes place after the harvest (often in December). The Koma sacrifice to their ancestors on a day called “Fire Festival” (Boling Taala Daang). Since its date is tied to the Islamic calendar and thus moves through all the months of the solar year, the sacrifices cannot be pure thanksgiving offerings.

The ancestral shrines, too, look different in the two groups. While in the case of the Bulsa one can recognize, by the placement and size of the shrines, to which ancestor generation the sacrificed shrines belong, among the Koma all shrines have the same size and shape. They are about the size of a personal shrine (tintueta-wen-bogluk) among the Bulsa. Sometimes the Koma landlord rebuilds the shrines only a few days before the sacrifice, occasionally only for those ancestors for whom a sacrifice is intended. When on one occasion the shrines of a compound could not be finished in time, all ancestors received their sacrifice on the cemented floor of the courtyard.

Koma ancestral shrines after a sacrifice

Straw torches swung during a fire-festival

Night performances with straw torches being swung by young people gave the Koma Fire Festival (Boling Taala Daang; the ‘fire throwing day’) its name. There is no comparable tradition among the Bulsa.

Moreover, the Fire Festival as a whole has a strong element of entertainment. There is dancing until late at night. On February 9, 2006, the appointment of new chiefly office-holders (kambonnaling, sing. kambonnaang) was set on the day of the Fire Festival and the ancestral sacrifices (Kröger and Baluri 2010: 53-56).

The established authorities of the kambonnaling do not quite correspond to the Bulsa kambonnalima. While the Bulsa kambonnaab is in charge of administrative tasks within a certain territory (e.g. Sinyangsa kambonnaab) and the English translation sub-chief may have some justification, the Koma kambonnaling are “chiefly office-holders” with a certain responsibility in the chief’s official household (see Kröger and Baluri 2010: 52). Among the offices there are, for example, the Nazua (“linguist”, interpreter, Buli biisitieroa), the Nanchinaa (youth leader), the Wudana (messenger; he leads the chief on official walks) and the Yagbing (in charge of dances and big meetings); in addition, there are about seven military officers, also called kambonnaang.

At least the chiefdom of Yikpabongo, which I have examined in detail, is also fundamentally different from that of the Bulsa. Yikpabongo has 2 clans (Habundeng and Bakodeng) with their own chiefs and without any marriage prohibitions between them. While in political and economic life each chief can make decisions without any influence by the other clan, in ritual life an institutionalized cooperation, based on reciprocity, has developed.

The two officiating women of a funeral

Of the many examples that are to be found, especially at funerals, only a few can be mentioned here.

1. The grave of a deceased person from Habundeng is dug by gravediggers from Bakodeng (and vice versa)

2. At a funeral, the leader of the women, sitting next to the effigy (suging) of a deceased person from Habundeng, must be from Bakodeng but being married in Habundeng (and vice versa).

3. Of the two officiating women of a funeral, one must have been born in Habundeng and married in Bakodeng the other must have been born in Bakodeng and married in Habundeng.

4. The sacrifice on the last day of a funeral is performed by a man from Habundeng if the deceased was from Bakodeng (and vice versa).

I assume that these close ritual interrelationships are intended to defuse potential tensions between the two clans. In one conflict that almost led to fighting clashes, it was the Habundeng women married in Bakodeng and the Bakodeng women married in Habundeng who deescalated this conflict. I am not aware of any similar arrangements, which are reminiscent of dual organisations, among the Bulsa.

As far as the material culture is concerned, only a few phenomena are immediately noticeable to a Bulsa visitor in Komaland.

The Koma live in nucleated villages and not in single farmsteads as the Bulsa originally did. In the past the Koma lived in round houses with thatched, conical roofs which are also predominant among the southern Bulsa. Moreover, I could observe some conical, thatched roofs on houses with square ground plans in Yikpabongo.

The circular construction of the compounds with surrounding mud walls can also be found in densely built-up villages like Yikpabongo so that sometimes only very narrow gaps exist between the compounds. In more recent times, the round houses with

Wooden dog’s trough

thatched, conical roofs have been replaced to a large extent by square houses with tin roofs.

There are also some differences in the construction techniques of buildings. I could observe only the technique of using unfired bricks made in wooden moulding frames. The first row of bricks is, however, not placed on a row or layer of natural stones, as it is usually the case with the Bulsa, but directly on the ground. Since the ground water can thus easily seep into the unfired bricks, the lifespan of these houses is probably shorter.

The Koma do not know pottery because good clay deposits are probably missing. This lack of clay has also led to material objects being carved from wood, while the Bulsa make them out of fired or unfired clay. While Bulsa dogs, for example, receive their food in a ceramic shard, the Koma carve their dog troughs from wood. Among the Bulsa animal figures, for example single or mating chameleons, are usually formed as reliefs on the central millet store after a diviner has given the instruction that a jadok-shrine has to be built. Koma carve these figures from wood for the same purpose. A jadong shrine (Buli: jadok shrine), thus created, receives sacrifices in both ethnic groups.

While the linguistic similarities between Konni and Buli probably point to a common origin of both ethnic groups, differences in religion – including the greater importance of Islam – and also in material culture can be explained by the long stay of the Koma as a guest people in the Mamprusi area. They did not settle in their present settlement area before the end of the 19th century.

Modern influences have lessened some of the differences between the two ethnic groups mentioned here. School buildings and health stations are built in the same one-storey bungalow style, not only in northern Ghana but also in other parts of Africa (cf. Kröger 2017: 57). Ceramic vessels have been replaced everywhere by cheap plastic and metal goods and the original natural religion with its pronounced ancestor veneration has become more and more displaced by Islam and Christianity.

Yikpabongo New Primary School. The small dark building on the right was the old primary school.

Endnote 1: G. Krause, a linguist and the first European who visited many towns and villages in Northern Ghana (cf. Kröger 2013: 109-110), was an anti-colonialist and did not cooperate with the German Empire’s goals of imposing colonies in Africa. This may be the reason that his scientific reputation was undermined in Germany (see Wikipedia’s article on “Gottlob Krause”).

Endnote 2: A correspondence of Konni initial h– and Buli initial p– appears also in other words, e.g. haari – paari (reach), hagiri – pagra (to be hard or strong), hagiriŋ – pagrim (strength). See also hamiŋ and haŋ in the list.

References

Kröger, Franz and Ben Baluri Saibu (2010): First Notes on Koma Culture. Life in a Remote Area of Northern Ghana. Münster, Berlin: LIT-Verlag, Brunswick, New York: Transaction Publishers (568 pp.).

Kröger, Franz (2013): ‘Means of Transport in History and Today (Northern Territories, Ghana).’ Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and History. No. 7: 109-113.

Kröger, Franz (2017): ‘Infrastructure of the Bulsa South District.’ Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and History, No. 10: 56-60.

Naden, Tony (1986): Première note sur le Konni. Journal of West African Languages XVI, 2: 76-112.

Wikipedia (English): Gottlob Krause. https://en.wikipedia/wiki/Gottlob

- Editorial

- Various Authors and Sources: Events

- Franz Kröger: Who on Earth Is Interested in the Bulsa? The Bulsa Internet Websites 2018-2020

- The 2019 Feok Festival – a Trilogy

- THE TITLE AND POSITION OF THE SANDEMNAB – A DISCUSSION

- Francis A. Azognab: Should Christians Attend Traditional Funeral Celebrations?

- Stephen Azundem: Exploring the Jewish Concept of Ritual Cleansing from a Bulsa Perspective

- Joseph Aduedem: The Art of Shepherding – The Origins of Conflict with Farmers in the Cultural Context of the Bulsa

- Joseph Aduedem: Kuub Juka or Ngomsika, the Second Funeral Celebration

- Franz Kröger: The Koma and Bulsa (Builsa) of Northern Ghana

- Franz Kröger: Can a Visual Perception be expressed by Sounds? The Buli Ideophones

- Franz Kröger: Good and Evil in Matter and Living Beings

- Franz Kröger: Roman Provinces and British Colonies — Living Between Two Cultures

- Franz Kröger: Sylvester Ateteng Azantilow 1950-2020 (obituary)

- MAIN FEATURE: CREATIVE BULSA: ARTISTS, POETS AND WRITERS

- Patrick Seidu aka Saala-Biik Soakatoa: My Life and Career

- Franz Kröger: Daniel Bukari, an Amateur Artist

- Eric A. Anadem, a Photographer and Artist

- Ghanatta Ayaric: Hard Road to Travel

- John Agandin: A Trotro Ride from New Town to Accra

- John Agandin: The Kayayei’s Tale

- John Agandin: Korona Vairosiwa Tugurika

- Ghanatta Ayaric: In the Meantime!

- Anbegwon Atuire: Rhythm of the War Dance

- Robert Asekabta: Continue Revolution

- Poems in BULUK 1-13