Joseph Aduedem

Sandema, Bilinsa-Punsa, 2019

(Photos taken by F. Kröger in Wiaga-Sinyangsa-Mutuensa and at the Wiagnaab’ Juka-funeral)

KUUB JUKA or NGOMSIKA, the Second Funeral Celebration

This part of the funeral celebration takes four days, except for a man of status (kpagi or a yeri nyono who had sacrificed to great ancestral gods) it takes six days (Aduedem Alanjo 2019). Since we have been dealing with the funeral of an average man, we shall look at this stage of the funeral rites with the four days format. Depending on whether the juka is following the kumsa (the first funeral celebration) immediately or not, the sons and other relatives of the deceased call the elders/landlords (nisomba/yie nyam) to come and perform their funeral for them.

FIRST DAY: KPAAMA NGABIKA DAI

On the first day, every nisomoa and yeri nyono comes to the house with millet (zaa) and the woman who ‘sits on the funeral’ (kuumu zuk kaldoa or chelie, the presiding woman) comes to sit with the widow (jam kali wa ngaang, literally: ‘comes to sit behind her’). When the elders arrive, they sit in the kusung dok as usual with their zaa (millet). The zaa are mixed together (from the various sources) and put into two traditional baskets (busiksa). The sons and other relatives provide tobacco (tabi), a fowl and an animal which are taken together with some of the millet from the two baskets to the grave by the gravediggers for the vorup chiesika rituals (chiesi = to collect; millet was collected by the elders). At the grave, they thrash (piag) some of the millet and use the grains to put all round the grave. Then the fowl and the animal are sacrificed similar to what was done during the burial rituals. These are gifts given to the deceased as he goes to kpilung – the home of the dead (Aduedem Alanjo 2019).

After that they come to the house and the elders thank them. The elders will call the presiding woman to the kusung and give her some of the millet and kpaama (Kröger 1992: pito malt, germinated guinea corn grains for the first stage of brewing pito). Before she can prepare pito (daam) from the malt it is ground (ngabi). This activity has given the name (kpaama ngabika) to the first day of the Juka.

When she takes the zaa and the kpaama inside, the sons and other relatives add a good quantity of pito malt that will be enough for the funeral celebration.

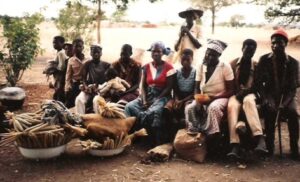

Having begged for resources (chiesika) (Wiaga-Mutuensa)

However, after she has entered, the elders share the rest of the zaa in the two baskets among themselves. Then they call the widow and ask her to go and beg for resources to perform the final funeral rites of her husband. This begging symbolises the dependence of the widow on the generosity of society.

She could go to one house in the morning, one in the afternoon and one in late afternoon. In any of these three rounds, when she gets to a house the men will give her zaa (millet) while the women could give her ingredients, shea nuts, etc. When she has taken enough rest after the third round, she goes to her san-yigmoa (link man in marriage affairs) house. He takes her to a diviner (baanoa) and divines for her. They will both return to the san-yigmoa’s house and the san-yigmoa’s wife prepares TZ (millet porridge, Buli saab) for her to eat. The san-yigmoa then brings her back in the night, by which time they would have ground the kpaama (pito malt) waiting for her to come before they put the malt-flour (kpaam-zom) into water.

When the kpaam-zom is kept in water, they announce it by shouting from one house to the other that “they have taken the diviner’s bag” (ba pa baan yuni yooo). Then every relative (especially the sons) will start preparing their pito for the fourth day. People (all visitors) start to sleep at the funeral house from that day on (gua kusung).

SECOND DAY: NYAATA SOKA DAI

On the second day everything significant is done towards the evening, e.g. the preparation of shea-butter, that is to be put in place. Towards late evening, a woman sets water in a clay pot on a fire by the rubbish heap (tampoi) outside the house. The widow, surrounded by women is brought out to sit also by the tampoi. Any widower whose wife’s final funeral rites have been performed is called upon to come to shave the widow. When the water (now called juom or juem) starts boiling by night time, the women ululate (nag weliing) in jubilation for the water boiling. There is joy because the boiling water shows there is no issue, “for when there is a problem, the water will never boil until the issue is found out (through divination) and solved” (Aduedem Alanjo 2019). When the water is boiling, the juem suoroa (a woman traditionally “trained” for that ritual) fetches some of it into a chari, an unrestricted open clay vessel (Kröger, 1992), pours some quantity of cold water into it and baths the widow surrounded by women to form a human wall. The widow is smeared with shea butter and daluk, a red clay paint used for painting pots and the human body (Kröger 1992), before bathing her with the hot water. This ritual bathing is called nyaata soka or juem soka (‘water bathing’) from which the second day celebration derives its name (nyaata soka dai). It is believed that “if the woman is innocent of her husband’s death, the hot water will never burn her” (Aduedem Alanjo 2019).

After bathing, the juem suoroa prepares TZ and bogta soup with mud fish for the widow, still by the tampoi. The widow eats that food alone, but any woman whose husband is late and his final funeral rites have been performed can eat that food too. When she has finished eating, the rituals for that day come to an end and the widow is led inside. She will rub her back against the dalong before she enters inside the room to lie down. While the youth could be drumming and dancing, all may depart if they wish.

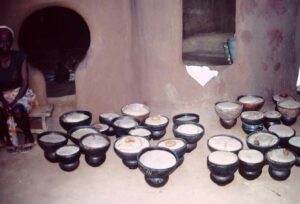

Bowls with TZ Juka Funeral of Asiuk, late chief of Wiaga

THIRD DAY: SIRA MANIKA OR LOG TUILIKA OR LOG JUKA DAI

On this day, they cook Bambara beans, yam, cakes (kamsa), ‘jollof’ rice, bumbota (Kröger 1992: tuber of Tacca Leontopetaloides), and an animal may be killed for preparing TZ. When the kobisa are coming back on this day, each comes with TZ. By evening time, the TZ that they have prepared in the house is served in several earthenware bowls including one very big one. TZ in a big earthenware bowl with a cake on top of it is sent to the kusung dok for the elders, and another TZ and cake is given to the san-yigmoa of the widow for his toils. The yam is arranged around the TZ in a big chari (which will be given to the kobisa kpieng, the head of the kobisa), and rice or bumbota are put on top of the TZ. Taking a chin sobli (a black calabash often used for dirty purposes), they put a number of mud fish, the Bambara beans, and the rice, inside it. All the bowls of TZ are arranged in the courtyard (dabiak) with the TZ in a big chari and together with pots of pito. Then the elders in the kusung are called in and told that this is their TZ, they should use it to perform their funeral. The elders pick four bowls of the TZ with some pots of the pito and give them out to be kept in the kitchen (gbanlong). After giving one bowl of TZ to the siblings (if any) of the deceased, they ask all to snatch (chiak) the rest of the food.

When the chiaka is over, the nisomba (elders) take their four bowls of TZ (kept in the gbanlong) and go to put them by the bui (barn) in the kraal (nankpieng) without uttering a word. After having taken the four bowls of TZ again outside and put them by the parik (outer wall) they call the kobisa to perform their sacrifice for them. Two of them get up and wash their hands with water. They fetch all the food items brought out plus bogta soup (prepared by the widow) into their left hands in the form of a mixture and smear that on the parik while mentioning the name of the deceased and saying: “ Fi ngandiinta ni nna, nuru bi ngman ka” (‘this is your food, there is no one again’). This ritual is done three times. Taking some pito, they pour it on the smeared food on the parik saying: “This is your drink, there is no one [i.e. the deceased person] again”, and after that they wash their hands. The rest of the food is eaten.

Next, the sons and other relatives call the kobisa (but two gravediggers from the kobisa will opt this time) to enter the courtyard (dabiak). In the dabiak, the sons and other relatives provide a cock and a male animal (either a billy goat or a ram), and the log and tom (quiver and bow) of the deceased are brought. White untwisted fibre (bok pieluk) is used to tie the quiver and the bow together. The cock and the animal are sacrificed on the quiver and the bow that is now tied to the quiver.

White, untwisted fibre and the damburing branch

While sacrificing, mention is made that his sons are giving him these things. Only those whose fathers are late and their final funeral rites have been performed can eat this sacrificed meat. After skinning the ram or billy goat, only its liver and a piece of meat from its forelimb (bogi) is roasted together with the fowl outside the compound. The presiding woman (chelie or kuumu zuk kaldoa) grinds salt and adds shea butter to it in a dark calabash (chin-sobili). The roasted meat is kept in the chin-sobili with salt and shea butter. It is used to sacrifice to the log again. Any time they are sacrificing to the log, they say, “Ngua fi nganta, nuri bi ngmang ka” (receive your food, there is no one again). After that they use some pito and pour a libation on the log. Then they can go and eat their roasted meat while the skinned meat is kept in the skin of the animal.

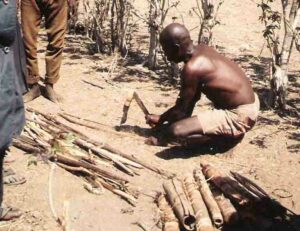

Ngmiena straws (Mutuensa)

When they have finished, they hang a damburing (branch of a damburing tree) on the gbong, a “flat roof of a house” (Kröger 1992). The log is then carried by the two gravediggers, each holding one side of it, and put on the danburing-branch on the gbong. Then they leave for the kusung (outside).

The women will prepare another set of TZ and all the other varieties of food prepared earlier. When they have finished, they will send a chari of TZ (saab ni chari) to the elders in the kusung saying they (the women) have finished. The elders will eat that TZ and when they have done so, those two gravediggers who performed the log ritual enter the compound again. After removing the log from the gbong, they send it inside the dalong. In there, they collect ngmiena (straws of elephant grass), spread them and put the log on them, and the ngmiena are rolled around the log and tied with bog pielung (white fibre). Another man comes into the dalong, sits down by its entrance and blows a whistle while the daughter-in-law, whose father is dead and his final funeral rites have been performed, uses ngmiena again, lights a fire and that fire brightens the dalong room for the following rituals. The TZ, yam, rice, cake (kuosa), bumbota, etc. that have been prepared are used to sacrifice on the log in the dalong a second time. Let it be noted that no one whose father is alive or dead but the final funeral rites are not yet performed is allowed to see the log kaabka (sacrifice on the log).

Two people carry the bows and quivers out of the dalong (Mutuensa)

A quiver is cut into pieces (Mutuensa)

Again, as the food is cut and put on the log, the “Nuri ngman ka nuri ngman ka” is repeated. When the sacrifice is finished, two people carry the log out while someone remains in the dalong watching the leftover food. As the two people move out with the log, the relatives of the deceased follow, mourning and wailing.

When they get to the kraal, they put the log by the bui and cut it together with the damburing into pieces, and the woman who set the fire in the dalong brings that fire and it is used to set the pieces of the log on fire. To “set on fire” in Buli is ju, its verbal noun is juka. This is the origin of the name given to that day of the funeral rites as juka dai or logta juka dai (the day of burning the quivers).

The quivers and bows are being burnt (In Mutuensa it is done outside the compound)

It is only at this point of burning the quiver (log) and bow (tom) or in the case of a woman, the destruction of the puuk that “the soul of the dead is released and can now properly enter the land of the dead. These rituals of destruction evoke strong emotional outbursts of close relatives because only then have they finally lost their relatives” (Kröger 2017). As the fire is burning, the sons of the deceased continue wailing and performing a war dance (lielik) since fire is burning their father’s quiver. This fire burning is also viewed in the form of natural fires disaster and that is why they perform the war dance as sign of their readiness to rescue their father’s quiver.

When the fire is about dying down, the two gravediggers tell the sons of the deceased to put it out. The sons bring a pot of pito and a hoe blade and these are put aside. The daughter-in-law (or the woman who stepped in for her depending on whether her father is alive or not) who set the fire in the dalong also brings another pot of pito and water. The two gravediggers taking her pito and the water, pour them into a calabash. All those present in the kraal, using their left hands, fetch the content (pito and water) in the calabash and wash their faces to wipe aware the tears from the crying, while moving around the burning quiver. The rest of that pito is poured on the fire and the hoe blade is thrown into it or perhaps its ashes, saying that they are quenching the fire burning their father’s quiver. The pito the sons brought earlier together with non-compulsory money of any amount is only to show the status of their father as nganta nyono, a man of wealth and is given to the gravediggers to use them to put out the fire. The rest walk out and the two men go inside the dalong to eat their food they left there. Some of the food is given to the one that blew the whistle, some to the woman who set the fire, and some TZ is put into the ‘black’ calabash (chin sobli) and handed to the woman to be given to the orphans (the biological children of the deceased) the following morning. That TZ is called kpingsa saab (orphans’ TZ). The woman takes that TZ and puts it somewhere, and the funeral rites on that day have come to an end.

FOURTH DAY: DAATA NYUKA DAI OR KUSUNGTA PUUSIKA DAI

In the morning of this day, the presiding woman (chelie) takes the TZ in the chin-sobli that she kept aside the previous night and sits down at the entrance of the dalong. Calling each of the biological children (from the oldest to the youngest), she cuts small pieces of TZ, scolds him/her and gives it to him/her to eat. She does that three times each for all the children. The scolding takes this form: “Ngoa, fi a kping ka nna, fi puom bagaa nya ka nna yeg-yega. Ka wana tim pa wa nganta a te fi a kping ka nna? (‘Take this, you are an orphan, you are even looking too much. Who will give food to an orphan like you?’)

The scolding is actually done to let the children come to the reality of the new social status as orphans. Note that until the final funeral rites of a person have been performed, culturally speaking the person is still alive and by implications, the children of the deceased are not considered orphans (even if it will take several years) until the final funeral rites are performed.

Afterwards, the elders in the kusung dok send two men inside to the presiding woman, to find out whether there is pito from the pito malt (kpaama) they gave her on the first day of the juka rites. The woman then calls the first son of the deceased and shows him the pito in the pots. The woman takes a pot of pito and the son takes calabashes (daam china, ‘pito calabashes’) and they send them out to the elders saying: This is dirt (dangta) of the deceased. Out of courtesy the elders would ask that some of the pito be given to the mothers in-law (nga niima) of the deceased who have come to witness the funeral rites. However, the sons would opt to provide different pito for their mothers- in-law. More pito may even be supplied and everyone drinks, hence the day is called Daata Nyuka Dai (pito drinking day).

Later, the sons provide a guinea fowl, prepare it by plucking its feathers and adding grains of millet (za bie). They give it to the link man’s wife (yigmowa powa) to send off the mothers-in-law. When they have left, the elders send two men again to the presiding woman, telling her to ask the widow who she wants to get marry to, since the funeral rites of the husband are over. The two men will do that four times. She can marry anyone from the extended family, and in the case of a polygamous marriage, she can even marry any of the sons of her co-wives, (but never her own son) or she decides to remain unmarried “by marrying the grave of her late husband” (Kröger 2017). After the fourth round, the presiding woman comes to the elders and announces the name of the man the widow wants to marry. This remarriage is “a ritual proper for the reintegration” of the widow into society, and after this remarriage the widow starts wearing her normal clothes again (Kröger 2017).

The person she mentioned is called by the elders and he is asked to provide a basket of millet, a guinea fowl, pito and tobacco. When he has provided them, the elders call the presiding woman and give the items to her. Those items are for the presiding woman, because the understanding is that the widow is her daughter and she has just handed her daughter’s hand in marriage to the said husband.

The sons also provide a fowl (chick) for the elders. And those responsible for sacrificing the wall in the gbanta dai rites of the Kumsa funeral use it again for the sacrifice to the wall. As they smear the blood on the wall, they say: “This is all, there is no longer a funeral in this house, and children may take the fowl and roast it”. The elders thank one another and disperse. The final funeral rites have finished. If the deceased was a landlord (yeri nyono), the elders will call all those (from the house) concerned to the kusung dok and tell the sons that their father is no longer there, therefore, the next landlord is Mr “A”, “B” or “C”.

One week later, the widow cooks Bambara beans (suma) and makes cakes (kamsa) and the man who shaved her (on the nyaata soka dai) is invited. He comes and shaves her again and after that, he removes the ropes she wore during the whole funeral rites performance. No one is supposed to see those ropes, so he buries them in the tampoi (rubbish heap). The widow then serves the man some of the Bambara beans and the cakes (kamsa). After eating, the man thanks the widow and tells her that the man she chose is duly her husband thereafter and he goes home. Everything has come to an end.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Akangyelewon, Evans Atuick

“Are Final Funeral Rites in Buluk Really Expensive”? Buluk. Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society No 7, 2013 (pp. 36-42).

Cardinall, A. W.

The Natives of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast, Their Customs, Religion and Folklore, New York: Negro University Press, 1969.

Kröger, Franz

Ancestor Worship among the Bulsa of Northern Ghana. Religious, Social and Economic Aspects. Hohenschäftlarn near München: Klaus Renner Verlag, 1982.

Kröger, Franz

Buli-English Dictionary. With an Introduction into Buli Grammar and an Index English-Buli. Münster and Hamburg: Lit Verlag, 1992.

Kröger, Franz

“Colonial Officers and Bulsa Chiefs,” Buluk. Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society No. 7, 2013 (pp. 89-103).

Kröger, Franz and Ben Baluri Saibu

First Notes on the Koma Culture. Life in a Remote Area of Northern Ghana. Berlin and Münster: Lit Verlag; New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers, 2010.

Kröger, Franz

“Kanjagas, Builsa, Bulisa or Bulsa,” Buluk, Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society, No.1, 1999 (pp. 44-45)

Kröger, Franz

“Remarks on the 2000 Ghana Population Census,” Buluk, Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society, No. 7, 2013 (p. 17).

Kröger, Franz

“Religious and Rebellious Elements in Bulsa Funeral Rituals”, Buluk. Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society, No. 10, 2017 (pp. 97-113).

Kröger, Franz

“Returning Home as a Dead Man, The Bulsa Ngarika-Burial”, Buluk. Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society No. 9, 2016 (pp. 53-61).

Kröger, Franz

“Southern and Northern Builsa: Co-operation and Competition,” Buluk. Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society, No. 10, 2017 (pp. 30-35).

The Liturgical Press Collegeville

The Rites, Volume One: Minnesota, 1990.

The main informant of the work in Buli was Aduedem Alanjo, Joseph Aduedem’s grandfather.

- Editorial

- Various Authors and Sources: Events

- Franz Kröger: Who on Earth Is Interested in the Bulsa? The Bulsa Internet Websites 2018-2020

- The 2019 Feok Festival – a Trilogy

- THE TITLE AND POSITION OF THE SANDEMNAB – A DISCUSSION

- Francis A. Azognab: Should Christians Attend Traditional Funeral Celebrations?

- Stephen Azundem: Exploring the Jewish Concept of Ritual Cleansing from a Bulsa Perspective

- Joseph Aduedem: The Art of Shepherding – The Origins of Conflict with Farmers in the Cultural Context of the Bulsa

- Joseph Aduedem: Kuub Juka or Ngomsika, the Second Funeral Celebration

- Franz Kröger: The Koma and Bulsa (Builsa) of Northern Ghana

- Franz Kröger: Can a Visual Perception be expressed by Sounds? The Buli Ideophones

- Franz Kröger: Good and Evil in Matter and Living Beings

- Franz Kröger: Roman Provinces and British Colonies — Living Between Two Cultures

- Franz Kröger: Sylvester Ateteng Azantilow 1950-2020 (obituary)

- MAIN FEATURE: CREATIVE BULSA: ARTISTS, POETS AND WRITERS

- Patrick Seidu aka Saala-Biik Soakatoa: My Life and Career

- Franz Kröger: Daniel Bukari, an Amateur Artist

- Eric A. Anadem, a Photographer and Artist

- Ghanatta Ayaric: Hard Road to Travel

- John Agandin: A Trotro Ride from New Town to Accra

- John Agandin: The Kayayei’s Tale

- John Agandin: Korona Vairosiwa Tugurika

- Ghanatta Ayaric: In the Meantime!

- Anbegwon Atuire: Rhythm of the War Dance

- Robert Asekabta: Continue Revolution

- Poems in BULUK 1-13