Adopted from:

Roland Hardenberg, Josephus Platenkamp, Thomas Widlok (Eds.): Ethnologie als angewandte Wissenschaft – Das Zusammenspiel von Theorie und Praxis.

2022, Berlin: Reimer Verlag, pp. 131-155.

Translated into English by Franz Kröger

THE BULSA EDUCATIONAL ELITE AS AN OBJECT OF ETHNOLOGICAL RESEARCH

Discussions in a Bulsa Facebook group

Franz Kröger

INTRODUCTION

A field researcher’s access to people of different age groups, genders and educational levels is usually associated with various hindrances or limitations. For a long time, the preferred Bulsa informant group were old men still fully integrated into traditional society due to their offices as elders, heads of traditional compounds, medicine men, or earth priests (sacrificers to the earth shrines) and who, because of their age, hold extensive knowledge about their culture and society. In modern research, particularly the study of gender, women play a major role. Likewise, children have become the focus of ethnographic interest in projects on education, games, school, etc.

For many ethnologists – including myself – the younger, educated elite has long been less attractive as a research subject than any of the above groups in traditional society. The advantage of conducting interviews in English with members of this group is more than counterbalanced by their often very limited knowledge of their own traditional culture or even their ‘mother tongue’. Many potential informants with a university education are also sceptical about a European field researcher. In my field research, I found people in this group to act as interpreters and help transcribe audio tapes, etc., but I always checked information about their own culture with the knowledge of old men.

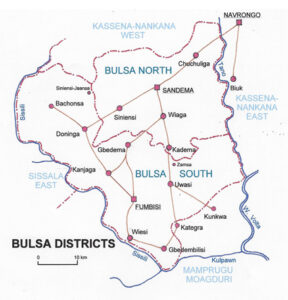

Map 1: Bulsa Districts (map: F. Kröger)

My field research among the Bulsa, an ethnic group of approximately 100,000 members in northern Ghana that used to focus entirely on agriculture in the past, spanned 16 research visits between 1972 and 2012 (Map 1). When it was no longer possible to continue my research because it had become challenging due to my age and difficulty with accessing or contacting Bulsa informants, some of whom were illiterate, I sought a way to continue my research; at that point, I encountered a Bulsa Facebook group on the Internet (Kröger 2015). As I had acquired an aversion to many social networks after my experiences in Germany – where participants would often chat extensively about banalities – it took me some time to recognise the value of a Bulsa Facebook group as a way to continue my research. I was not so much interested in collecting new data on various ethnological topics as I was in analysing the attitudes of the educated class towards ethnologically relevant areas of Bulsa culture. For this reason, I have not corrected information in the following articles that I found incorrect before the background of my earlier research.

The first Facebook group among the Bulsa, ‘Bulubisa Meina Yeri’ (literally: ‘a home for all the children of Bulsaland’; from here on, it is referred to as BMY), was created on 4 July 2011; it had about 3000 members when I joined. The only restriction for all participants (endnote 1) was that they were not allowed to discuss party politics, which would affect the unity and harmony of the friend group. Some members did not agree with this restriction, so they founded their own Facebook group on 26 February 2015, calling it ‘Buluk Kaniak’ (‘Lantern of Bulsaland’). For unknown reasons, almost all of the first group’s members also became active in the second group, while BMY lost much of its importance.

Buluk Kaniak is a ‘public Facebook group’, so a foreign visitor can freely access all its posts. According to John Agandin (an administrator of Buluk Kaniak), for the period from 14 October 2021 to 10 November 2021, the average number of visitors to Buluk Kaniak per day was 964, the average number of comments was 11, and the average number of responses was 39 (written communication).

I conducted an analytical study of the BMY Facebook group during its heyday (before 2015) and published the results in the journal Buluk 8 (Kröger:2015). My conclusions about BMY also generally apply to Buluk Kaniak (Kröger:2018).

According to this study, around three-quarters of the participants had attended university or college (endnote 2). From a sample of 200 participants, 151 provided information on their place of residence in the Facebook ‘About’ section: 80 (53%) lived in southern Ghana, 46 (30%) in the north, and 25 (17%) were abroad. The collected religious affiliation data (from 88 participants) showed the following distribution: 82 (96%) Christians, 3 (3.5%) Muslims, 1 Rastafarian (1.2%), 1 Freethinker (1.2%), and 1 Traditionalist (1.2%). About one-third of the participants were female.

The following topic groups were and likely remain the most popular:

1. Current information

Current news played a significant role in the early years of the Bulsa Facebook groups, a time characterised by a lack of newspapers, computers with Internet connections and poorly functioning or non-existent telephone connections. Even today, the Bulsa living in the diaspora should be and want to stay informed about the most pivotal or noteworthy events in the Bulsa District, including new regulations (e.g., the ban on the sale of strong alcoholic beverages in the compounds), the results of sports competitions, deaths, exams passed, etc. Numerous photos and videos also appear in this thematic group.

2. Culture and history of the Bulsa

The founders of the BMY group particularly sought to familiarise the educated Bulsa elite with traditional culture and history through contributions. In addition to topics such as those presented in this essay, the Buli language is also of great interest. An English translation is often sought for Buli words or phrases or vice versa.

3. Entertainment

Here you will find short stories, jokes, riddles, poems, etc.

4. Religion

There are no arguments between followers of different religions or denominations. Christians wish Muslims all the best for the beginning and end of Ramadan, while Muslims congratulate Christians on Easter and Christmas. The numerous religiously motivated posts, prayers or thank-you messages bear witness to the deep religiosity of many members.

The study of African Facebook groups by ethnologists is currently one of the less practised areas of research. In my initial contacts with Bulsa Facebook groups, I saw myself primarily receiving information regarding current events and data on Bulsa culture and history. It was only at a later stage that I tried to contribute the knowledge I had acquired through field research and archival work by actively participating in the discussions. This activity took place within the framework of applied anthropology.

According to Sabine Klocke-Daffa (2016:61), academic anthropology has a responsibility to make complex anthropological knowledge accessible to the general public in an understandable form of presentation. In this sense, I have previously had the opportunity to apply such applied anthropology methods several times. As one example, in geography and social science lessons at a secondary school and in an ethnological study group at the same school, I was supposed to translate field research results and theoretical approaches to their interpretation into a language suitable for pupils and to select content that pupils found interesting.

In the large Bulsa exhibition of 2005 (at the Westfälisches Museum für Naturkunde Münster), Miriam Grabenheinrich, Sabine Klocke-Daffa and I, together with students from the Institute of Ethnology at the University of Münster and the Department of Design at the Münster University of Applied Sciences (Fachhochschule), attempted to use my collection of objects from the material Bulsa culture to make the findings of scientific ethnology comprehensible to a non-ethnological and mostly non-academic public (Grabenheinrich and Klocke-Daffa 2005 and Klocke-Daffa 2015).

The engagement with Bulsa Facebook groups represented a completely different field of activity of applied anthropology, as the interlocutors possessed a markedly different knowledge of Bulsa culture from the participants in the projects mentioned above. The Facebook participants were by no means unfamiliar with traditional Bulsa culture; almost all had grown up in it, at least in their early years, but had then more or less immersed themselves in a second, Western culture at secondary school (often boarding school) or at university. Some now feel safer and more familiar with this second culture than the Bulsa culture they only experienced for a few years at home.

The ethnologist participating in the discussions did not always have a knowledge advantage. Some participants had superior knowledge to the ethnologist due to their later involvement with their culture and knowledge of the Buli language, even if this was not always perfect. Therefore, the ethnologist’s role consisted less of presenting his scientifically analysed facts and using written sources from literature and archives but more of learning and actively listening.

DATA ACQUISITION THROUGH PASSIVE PARTICIPATION

Below are some constructions from my material that should introduce the reader of this article to the subjects of the subsequent discussions.

The Kantosi, a foreign ethnic group in the Bulsa area

(Facebook after November 2017)

In his study on the ethnic group that I. Wilks (1989) called ‘Old Muslims’, he writes that the group moved south from the old Mali Empire (which peaked in the thirteenth–fourteenth centuries) to various regions of present-day northern Ghana. A subgroup of them, the Kantosi (Kantusi, Kantonsi), settled in Kpalewugu (50 km east of Wa in the Upper West Region of Ghana), and from there, some moved – probably at the beginning of the twentieth century – to Bulsaland, especially to Sandema. Of the approximately 2300 (2003) Kantosi of Ghana, around 280 to 400 live in the Bulsa District today (Ethnologue 2021: ‘Kantosi’). Most are still active in commercial industries (e.g., as traders, entrepreneurs, taxi drivers or mechanics). They built the first modern hotel in Sandema and set up general shops in Bulsaland. They also continue to provide a war dance group for the annual Feok festival in Sandema, which commemorates the victory of the Bulsa over the slave raider Babatu (Apen 2015). The leaders of the two large mosques in Sandema are Kantosi.

In addition to the nomadic Fulani (Fulbe, Peuls) pastoralist groups, which are difficult to quantify, the Islamic Kantosi (Buli: Yarisa) people are probably the largest African foreign group in Bulsaland. Today, almost all of them speak Buli in addition to their language, Kantosi, which is related to the Gur language, Dagara.

The Bulsa Facebook group Buluk Kaniak has a high degree of agreement about how to assess the Kantosi: They are seen as an educated, civilised, well-integrated minority who have significantly contributed to the economic development of Bulsaland and with whom there are no conflicts.

A.L.A. (endnote 3): The Kantosi (Yarisa) of Buluk are real Bulsa […] the Kantosi (Yarisa) brought modern civilization to our land […] The Kantosi served our kings as very educated people. Their contribution to Buluk history is so great. Chiefs before Sir Naab Azantilow respected them […].

L.A.: […] The Yarisa in Buluk are a well integrated group and have contributed in diverse ways to the development of Buluk including agriculture, trade and commerce, tradition and culture, transportation, religion and other areas.

A.E.A.: […] they might have introduced Islam to Buluk.

P.A.A.: […] there was a general discomfort in accepting strangers in our settlements. So, because of this discomfort, when the chief took the decision to allow the Kantosi/Yarisa to settle in Sandema, our people were not comfortable. A precondition for accepting them was their show of good behaviour. I must confess, in all honesty, they more than showed this even in the wake of provocation from the natives […]. I grew up hating this phenomenon but it reduced over time as the Yarisa left their Islamic school and joined the natives in the government schools over the years.

L.A.: Though A.L.A’s saying that the „Yarisa” should be regarded as Bulsa is well intended, I think it is a misplaced call. I think the identity of any person or group of persons should not and must not be sacrificed on the altar of integration or unity or even their longevity of settling at any place. To say these people are Bulsa is to deny them their language, traditions, music etc. […] We must embrace multiculturalism! Let us respect the identity of people…Has there been research that confirms these people want to be called Bulsa? Let’s not force our identity on people!

L. A.: […] We cannot say that there is full integration when the „Yarisa“ feel intimidated to contest elections to be Assemblymen or MPs […]. This is discriminatory and an abuse of their rights! Northerners and for that matter Bulsa are quick to say Asantes, or more generally Akans, are discriminatory, yet we are worst! […] The „Yarisa“, most of whom were born and bred in Buluk and have contributed to its development, have no better home than Buluk. The iron curtain that prevents them from full political participation must be lifted!

Le. A.: […] people of this tribe (the Kantosi) have a [more] violent and controversial character than we, the natives.

A.L.A.: I even think that they must be allowed to vote for chiefs. They also have house owners (endnote 4).

K.A.: I have been reading what has been said and want to express my displeasure with Radio Bulsa regarding the use of the Kantosi language. I do not think it is necessary, nor does it make sense to read news in Kantosi, after the same has been read in Buli! Don’t the Kantosi understand Buli? Are there two competing languages in Buluk? I have no problem with special programmes in Kantosi in keeping with our multicultural nature but I am vehemently opposed to news in Kantosi!

A.E.A.: Remember these are a people who have a culture that they want to pass on from generation to generation and their language is part of that culture. For me, it is most appropriate to give them a modicum of space in our airwaves once they do have distinguishable cultural practices that are not germane to Bulsa culture.

Since tribalistic and local patriotic attitudes are also present among the social networks of the Bulsa, the exceedingly positive evaluation of this foreign group is unexpected. Only one participant (L.A.) adopts a critical attitude, and another (P.A.A.) corrects his earlier negative view after having positive experiences with this group.

The discussion tackles high-level concepts and topics, including the issue that is also controversial in Europe of whether immigrants in Europe should be completely assimilated culturally or whether they should be allowed to live out their own culture in a multicultural society. Indeed, there is no lack of self-criticism. For example, the Bulsa people are accused of having a more discriminatory attitude towards foreigners than Bulsa emigrants experience in the southern cities of Ghana. The participants’ arguments may have been influenced by their knowledge of similar discussions in European countries or by reading international press products. Notably, one of the panellists received his doctorate from a university in Berlin.

Bride kidnapping and forced marriages in Bulsaland

The customary courtship among the Bulsa begins with visits from the suitor and his group of friends to the parents of his desired wife (endnote 5). Although the prospective husband offers plenty of gifts on these occasions and later, a bride price is not practised among the Bulsa. After these visits, which consist mainly of greetings with gifts but without any religious or ritual activities, the group of friends takes the bride to the groom’s compound, usually after dark.

In addition to other forms of courtship and marriage, such as through an arrangement by the parents (in-law) or after a girl’s premarital stay at her future husband’s compound (endnote 6), it still happens today that a courted bride will be abducted by the suitor’s courting group after she, for example, visits the market. Sometimes, she will be brought to the groom’s house by force. However, it seems to happen more often that the bride agrees to this ‘bride kidnapping’ and only feigns a token resistance.

The reason for the discussion on the subject of ‘bride kidnapping’ in the Buluk Kaniak group was that the son of a Bulsa chief had abducted a student by force and then considered her to be his lawful wife.

J.A.: […] Some women were forcefully captured and taken to men whom they hardly knew. I have personally rescued two women from such capture and nearly got beaten up once for intervening. This practice of capturing women seems to have slowly become a custom in its own right. This is why our traditional authorities should step up and pass some by-laws to outlaw this shameful practice once and for all. It simply has no place in modern society! I call upon our traditional council and especially the queen mothers of Buluk to rise up against this outmoded practice. I will give them the coming weeks to do so, but if it is not initiated, I would draw up a petition to the council to outlaw the practice and introduce a new ‘tradition’. Buluk must rise!

M.Ak.: As you explained, it was seen as dishonouring for a lady to show outward willingness to follow a man to his house as a wife. And I dare say it’s in ladies to shelve any interest they may have in a man. Thus, the practice of carrying a lady shoulder high home amidst bridal songs was a way of protecting the egos of ladies in their so-called fear of being called cheap. It was never meant to be forced marriage. Unfortunately, miscreants came abusing it. The practice was banned by late Nab Sir Dr. Azantilow as a result of the abuse of it.

J.A.: The practice of catching women might have been banned but it was not replaced, so people have no alternative to it. Like every social activity or dominant belief or practice, criticism and banning may not work if there’s no alternative route to be taken, hence my wish for the traditional council to introduce a new custom.

G.A.: J.A., you are right about finding an alternative option to the practice […] I think there is already one […] EDUCATION […] in your own words from your earlier submission: „many people (including myself) have been able to negotiate this process peacefully“ […] the many people are the EDUCATED […].

J.Am.: Eloping is an age-old Bulsa traditional practice even though legally it’s a crime. Some parents double-cross potential suitors by throwing their weight behind those who shower them with more gifts even though those might not be the girl’s first choice. So, elopement becomes the only option.

A.S.G.: […] See, none of the things that were practised by our forebears were/are bad as modernity is trying to make us cast a slur on all (even FGM [Female Genital Mutilation]). […] There is no real need these days in elopement since ladies are more open to love issues now than then. In fact, let’s not always be quick to condemn the then actions of our forebears, many of us are products of their actions, let’s only talk of refining them because of the change in time and taste, tnx [thanks].

A.L.A.: […] I insist that there is this love catching. I also know that some folks especially from chief houses abused the system. […] I don’t think bride capture is an issue today. It is rare.

J.A.: Not true, it only seems so because it is removed from the main towns! It is still the order of the day in the villages and other „far off places”. The trend in the towns is more of cohabitation than capturing. I have personally witnessed the rescue of two women captured in Sandema market by people from Dogninga and locked up in the house of another person from Dogninga waiting for the cover of darkness to take the sobbing bride home. The cases were reported to the police and the women released.

C. A.: […] In the Bulsa tradition we have ‘handing over’. There are two ways through which a man can get a wife. These are: Dogleenta and Dueni Deka [endnote 7]. In the case of dogleenta the parents of the girl will willingly give her out to their relative, friend etc. who may later give her out in marriage to someone closer to them when the lady is of age.

Now when we talk of dueni deka (courtship), before such type of marriage is properly contracted the young man and his kinsmen have to visit the house at least three times. The first visit should be the suitor and his friends while the subsequent visits will be [to] the young man’s father (if he is alive and strong) and some elders. So, on the day of the marriage (often determined by the bride’s parents) the mother of the lady will remove a fresh calabash from the zaaning (pieces of rope fastened together used in keeping calabashes) and lead her daughter together with her suitors out of the house before she hands it over to her. This is what we call nisa nari pai teka [hands- wash- take- giving]. Why capturing of women has come to be part of marriages in Bulsa custom is that, in those days women were fewer than men. So it was common to have more than five men seeking the hand of a young girl. For that matter, in order to outdo one another others would employ that as a measure. Sometimes the ladies themselves can compromise to it. This is when the parents are forcing her to marry someone she does not love.

J.A.: […] You know that when a girl is ‘caught’ and spends a night in the house of the catcher, the ‘marriage’ would be considered to have been consummated (whether or not it actually happened) and thereafter, she cannot marry any other man from the clan of the first man who caught her. This limits the marriage market for the girl now, no bi so [isn’t it so]?

A.E. [female]: I used to enjoy the catching especially the first day when the girl be pretending not to like the deal.

In a sense, the discussion about bride kidnapping exemplifies the attitude of the educated class of Bulsa towards similar phenomena of traditional culture that are difficult to reconcile with the ideals of modern society, such as the integrity of the human person and their free self-determination. A discussion about FGM (female genital mutilation) or the cutting of tribal marks would probably have led to similar results. The educated Bulsa are usually very tolerant towards traditional society’s purely religious activities, and many Christian or Muslim Bulsa participate in them. They also realise that traditional religion is an integral part of the Bulsa culture that they hold in high esteem; indeed, it contributes to their identity as Bulsa. The cultural elements mentioned above (bride kidnapping, FGM, and scarification) are, however, unacceptable to most of them, especially since they are probably teased and reprimanded for these customs in their environment outside Bulsaland.

As such, Facebook discussions also help the educated elite begin to separate the acceptable elements of their culture from the unacceptable ones and, if possible, eliminate all backward and degrading customs, rites, or institutions.

Epilogue: After only male Bulsa had held this discussion on bride kidnapping, sometimes with strongly appositional arguments, the last and only female participant was a Bulsa woman [endnote 8] who had herself experienced an abduction. She briefly remarked, ‘I used to enjoy the catching, especially [on] the first day when the girl [will] be pretending not to like the deal’.

In addition to the two topics debated here, participants discussed other topics in which ethnologists might find some interest: Are chiefs allowed to have an official English name or an Akan name? Does a Feok festival in Accra jeopardise the unity of all Bulsa? Which Buli words should be used for modern English terms (e.g., television, names of diseases, bacteria)?

Polemics on issues from Bulsa history

The discussions about the Kantosi and the bride kidnapping have shown that the participants in the Bulsa Facebook group present their arguments factually and rationally. In addition to debates over party politics, however, one topic that always leads to contentious and sometimes not entirely objective discussions is Bulsa history [endnote 9] – or, more precisely, two topics from Bulsa history: the ancestor Atuga, who immigrated from Mamprusi land, and the Bulsa battles against the slave raider Babatu (Kröger 2008). Other historical topics, such as colonial history or the period before and after Ghana’s independence (1957), seem less controversial, perhaps also because the attitudes of educated Bulsa towards these topics are relatively unanimous.

Atuga’s immigration as the basis for the division into North and South Bulsa

Map 2: Mamprusi Districts (map: F. Kröger)

As I have explained in an essay (Kröger 2013), at least eight versions of the history of Atuga’s immigration exist. Common to all versions is the idea that Atuga was a son or close relative of a Mamprusi king (see Map 2) who left the royal court because of a conflict. According to some versions he settled in Bulsaland with his family south of Sandema (Atugapusik), according to others in Kadema, where his ancestral shrine still stands and receives sacrifices. According to one legend, Akadem, Awiak, Asandem and Asinia, Atuga’s four sons, founded the four Bulsa towns of Kadema, Wiaga, Sandema and Siniensi. From the beginning, they and their descendants mixed with the indigenous Buli-speaking population (more narrowly, the Bulsa). The descendants of Atuga in the four villages or towns are still called Atugabisa (the children or descendants of Atuga).

The exact date of his immigration is not known. However, since all versions assume that Atuga left the royal court in Nalerigu (not Gambaga) and that the Mamprusi kings had moved their residence from Gambaga to Nalerigu around 1760, the immigration must have occurred after 1760. Further facts (Kröger 2013 and Perrault 1954) suggest that his departure took place under the Nayire (king) Atabia, who, according to Perrault, ruled from 1760 to 1775.

The above raises the question of why these historical events can still lead to such heated debates today. The events are not what ignites such conflict – rather, their consequences, which continue to this day and lead the Facebook group to engage in controversial or contentious discussions.

Oral tradition offers several indications that the integration of Atuga’s family into the indigenous Bulsa society took place without conflict. Today, however, apart from Chuchuliga, every Bulsa feels that he belongs either to the Atugabisa (North Bulsa) or not (South Bulsa); likewise, he feels strongly that he is an inhabitant of a village and a member of a lineage. Each of these positions is tainted with a kind of local patriotism that has strongly influenced the arguments in the discussions. Despite the educated generation’s status as being, in general, alienated substantially from their indigenous culture, such an individual’s prestige increases if he can prove that his ancestors (e.g., Atuga or the defeaters of the slave raider Babatu) are part of a glorious history.

The person of Atuga has also become a point of attack for Southern Bulsa, as some doubt his historical existence – for example, some regard him as a purely mythical figure or the immigration of his family is deemed a fairy tale.

A.L.A.: Some of these stories [about Atuga] are fairy tales and complete lies […] I just don’t believe the fabrication that villages were founded in Buluk by Mamprusi people […].

These people like Asam may even be aboriginal Bulsas. The Mamprugu connection is not likely. Mamprusis settled in Bawku. They are there still with their language and culture […]. I don’t dispute that there has been movements. We have many Moshies settled in Buluk. Tallensis too settled. These Tallensis in some cases till date speak their language. So I do not doubt that some Mamprusi few migrated. However their presence never really had any impact as we are being told.

A.D.: I will agree with you [A.L.A.]. Atuga did not come to the Builsaland with an intention to build a Kingdom. And none of his descendant has ably built a Kingdom. There has never been a Builsa Kingdom and there will never be. But it must be emphasised that once upon a time there lived a man called Atuga who settled on Builsaland and successfully built a wonderful family […].

A.L.A.: […] What this lone Mamprusi Atuga and his sons came to Buluk for remains a myth.

R.A.: It is unfortunate how some people always want to denegrate [denigrate] our folklore. We know that this has been passed down from generation to generation in oral form and will definitely change or get distorted of the numerous generations. Nonetheless, it is this folklore that has kept us together over the years.

A.L.A.: R.A., if you really sit down and examine these tales in a modern context you will be happy about my take. On the history of Buluk I have always chosen the late Rev. Agalik path of intellectual reasoning truth. Clearly Atuga is not founder of Buluk. If he even existed there we may need to investigate that further. His importance may actually be linked to deception about some magic that he cleverly used to lure people.

A.L.A.: My talk about language is just to illustrate that the talk about Atuga and his sons may be exaggerated. These people are not really founders.

Even today, the traditions of Atuga and his sons provide the basis for controversy-laden discussions between the North and South Bulsa. For example, a group of ethnologists from Münster R. Schott, B. Meier, U. Blanc, M. Striewisch and F. Kröger; see bibliography) who have carried out intensive field research in the Bulsa area since 1966 are accused, with some justification, of having focussed their work on Atugabisa sites (Sandema and Wiaga). I have also been labelled as obsessed with the Atugabisa.

In important decisions, the North Bulsa (Atugabisa) and South Bulsa act as groups with their own opinions and goals (Kröger 2017b:30–35). When the first Paramount Chief was elected (1911), the Atugabisa in Sandema, Wiaga, Kadema, and Siniensi voted in favour of the Sandemnaab Ayieta; residents of Fumbisi and Kanjaga (both South Bulsa) voted for the Kanjaga chief; those in Gbedema, Doninga, and Uwasi abstained.

In the 1969 general elections, Lydia Azuelie Akanbodiipo, a member of the National Alliance of Liberals (NAL) from Siniensi, was elected MP (Akandzenaam 2013). An enthusiastic NAL member expressed to me his joy at this success but also noted that the party must field a South Bulsa candidate in the next general election.

Attitude towards Babatu and questions about the title of the Sandemnaab

A second historical event fuels the controversy between North and South Bulsa: the battle (or battles) won by Sandema with the help of other Bulsa villages against the army of the Zambarima slave raider Babatu. In the late 1880s, the Zambarima (Zabarima, Djerma) raids on the stateless peoples of northern Ghana (including the Bulsa) peaked. Under the leadership of Babatu, they launched their attacks from the Zambarima camp in Seti, which today lies in Burkina Faso (Kröger 2008).

Although there are no contemporary written sources about this event, it is common knowledge among the Bulsa that a united Bulsa army defeated Babatu in a battle at Sandema. In my essay on the history of the Bulsa (Kröger 2017a), I tried to prove that there were two such battles: one south of Sandema near today’s Boarding School and one at Sandema-Fiisa, not far from the Azagsuk earth shrine. Sandema had supreme command in both battles and was joined by armed warriors from several Bulsa villages (e.g., Wiaga, Fumbisi, and Kunkwa) and even from Navrongo (information from the Sandemnaab Azantilow). After these victories, Sandema probably claimed a leading role over other Bulsa villages, which was also sought to a certain extent by the village of Kanjaga, especially before the battles.

Babatu suffered a decisive defeat in the well-documented battle of Kanjaga on 14 March 1897 (Duperray 1984:101). He was decisively defeated there by a French colonial army and Babatu’s mutinous warriors under their leader Amaria (Hamaria). Shortly before, Kanjaga had been invaded by the Zambarima, and, contrary to previous custom, Babatu did not kill the Kanjaga chief when he had promised to cooperate. After a few more minor skirmishes, Babatu settled in Yendi, where he died around 1900 from the bite of a poisonous spider.

When the British colonial rulers later wanted greater centralisation of the Bulsa chiefdoms under a Paramount Chief, most Bulsa chiefs opted for the Sandemnaab Ayieta in the election of October 1911, as noted above. In support of this choice, the Bulsa and British both emphasised Sandema’s formidable defensive posture against Babatu.

This role of Sandema is still cited today as a justification for the outstanding position of the Sandemnaab. If it can be proven that Babatu was not a cruel slave raider but an African national hero who rebelled against the invasion of the French and British, then the justification of the Sandemnaab as Paramount Chief would also be questioned. A Facebook participant from Kanjaga writes:

A.L.A.: …We all know that the slave trade lasted so long before Babatu was even born. How can he now be a victim vilified for this trade? The real actors involved in the heinous brutality are the Europeans. Records show that Europeans actually got to the hinterlands in Ghana to capture slaves. That can date back to 16th 17th 18th centuries. Where is a Babatu link? To make Babatu a scapegoat in order to conceal this criminal past is unfortunate. And to associate our religious festival [Feok] to that is insulting. Heroes like Amaaya [= Amaria?] and Babatu must be celebrated for resisting the colonial imperialist that engaged in slave trade. There was nothing like slave trade in the era of Babatu… Babatu is an African Hero….

Little is known about criticism of the Sandemnaab as the Paramount Chief during the colonial era and in the first decades after Ghana’s independence in 1957. This changed when Bulsaland’s political structure took on a different shape in the 2010s. In 2012, the central government of Ghana divided the Bulsa District into Bulsa North and Bulsa South (see Map 1). The boundary between the two districts largely corresponded to that between Atugabisa and Bulsa South [endnote 10]. Fumbisi became the new administrative capital of the Bulsa South District, and its chief was subsequently given the title of Paramount Chief. However, the Sandemnaab continued to be regarded as the primus inter pares of all Bulsa chiefs. After the death of a chief, his successor would again be elected by the compound heads of his village in Sandema.

In 2018, the central government elevated the chiefs of the Kanjaga, Wiaga, Siniensi and Gbedema villages to the rank of Paramount Chief. Thus, they now had the same status as the Sandemnaab.

Accordingly, the question arose as to how the primacy of the Sandemnaab should be duly expressed. After the new paramountcies were created, the title ‘Overlord’ was frequently heard, especially from representatives of the Sandemnaab’s family. This title also appeared in the Facebook group, where it was sometimes heavily criticised or defended. The first bone of contention in this controversy was a picture of the Sandemnaab that was uploaded by an administrator and labelled as a profile picture of Buluk Kaniak.

E.A.: Is he [the Sandemnaab] the only Builsa chief??? Sometimes, I just don’t understand!

B.W.: E. A., he’s the overlord and not just any chief if you care to know.

E.A.: B. W., Overlord??? Perhaps you need to revise your notes on the use of that term in history and traditional governance. Buluk is not a kingdom! The Sandema paramountcy is a colonial construct. It has no historicity, relevance and validity […].

B.W.: E. A. Sir, after visiting my notes I found out what the meaning of overlord meant in the past and [it] still remains the same. You’re right Buluk is not a kingdom but a chiefdom. and there’s a leader of all the other chiefs who is the overlord.

E.A.: B.W., kindly permit me to help you. You can’t at no point refer to a paramount chief as an overlord of a non-centralized tribe! This is because in these societies the status of a paramountcy is a product of a western / modern political structure attained by elevation. What it means is that the system is not static and that a hitherto sub-chief when elevated to a paramountcy is independent and equal to any other paramount chief within that area. On the other hand, in centralised societies where there are kings, sub-chiefs can be elevated by the modern governance structure but are still obliged by tradition/law to be accountable to their Kings. That is why a king is often referred to as an overlord. It’s vital to note that, all kings are overlords but not every paramount chief is an overlord. Sandem Naab is a paramount chief.

E.A.A.: Buluk has a paramount Chief and no Overlord because we are not a kingdom but a glorified chiefdom with autonomous villages which were forced into a chieftaincy system created by the British. The title „Overlord” is an Abilyeri invention as much as „His Royal Highness”.

M.Ak.: For A.L.A. and others to have problems acknowledging Sandem and Sandemnab rightful political authority in present day Buluk on a wobbling premise of what was in the past is nothing short of sour losers/envious skin pain. The relics of our colonial masters have lived with us to this day. Let those who want a reversal, pursue it holistically and not a convenient selective satiation of power rivalry.

F.L.: Now to the word overlord, it can be misleading but it could be taken to mean whoever enskins Builsa chiefs could be termed as overload. These are all semantics and we should not be seen to be offended by it. I will suggest that A. L. A. alternates pictures of Chiefs in Buluk. It brings about unity. […] I think more paramountcys be created in Buluk, which would enable the Sandem Nab elevation to the Presidency.

M.A.: I think there are few people here on this platform who are interested to see Buluk divide! I heard someone comparing Buluk to Navrongo, hmmmmmmmm, so sad, what I have to say is, do you want our beloved Buluk to be like Navrongo where there’s no unity amongst them! I fear!!!! If I was in the position of the Paramount Chief, I’ll be comfortable and not to champion the elevation of sub Chiefs into Paramouncies, because people are already ringing all the negatives bells you can think of!! I rest my case!!!

F.L.: […] Are you [K.A.] offended by some of us saying we don’t have an overlord in Buluk. Oh I see, you want to glorify the overlord title and for that reason you see it as a denigration if that title is not accorded.

[…] This is the meaning of overlord […]: a ruler, especially a feudal lord. „Charles [the Great?] was overlord of vast territories in Europe”. Do we have a feudal system in Buluk? Some of you just want to use words to feel superior over people. For what gain? I pity you.

A.L.A.: […] We have a head chief whose role is accepted. Chiefs are elected by their own landlords. No landlord from Kanjarga can go to Wiaga to vote a chief.

F.L.: K.A., what is wrong with me saying I recognize your father as the leader of the Builsa chiefs but not an overlord? Is this an insult?

E.A.: […] It’s imperative to state that the discussion is not about power rivalry among royal families of BULUK but the ‘legitimacy of equality of each SKIN.’ Anytime we raise questions about the Sandema SKIN, some people are always offended with the claim that it will disunite BULUK! Why???

[…] what I know is that all Builsa Villages were equal and independent until the advent of the British. This can never be a myth!!! The Indirect Rule system called for the Centralisation of power and creation of a Pseudo-Paramountcy. Friends of the British were empowered. These are HISTORICAL FACTS. No one can distort our history!!!! Kindly read Francis Afoko’s write-up, The Ayietas [Asianab Afoko 1970].

When the discussion about the position and title of the Sandemnaab had almost died down, a copy of a letter from the Bulsa Traditional Council that was signed by the Sandemnaab and addressed to the President of the Upper East Regional House of Chiefs in Bolgatanga appeared on Facebook. In it, the decision of the Traditional Council on 5 May 2020 that the name ‘Sandem Nab’ should be replaced by ‘Bulsa Nab’ is communicated. Although this decision was withdrawn shortly therafter, it caused unrest and strict opposition among the South Bulsa. Two concerned citizens submitted their objections in a letter to the House of Chiefs, which the Sandemnaab then rejected in a lengthy letter [endnote 11].

In the Facebook group Buluk Kaniak, the old discussion about the title and the position of the Sandemnaab was reignited; notably, the arguments and opinions largely corresponded to those from earlier times.

In all the various statements, the following names and titles of the Chief of Sandema have been used: the Chief of Sandema or Sandemnaab, Paramount Chief, Overlord, King, His Royal Highness, Leader, President, and Head Chief. He currently only officially bears the titles of Sandemnaab and Paramount Chief.

MY PARTICIPATION AND CRITICISM OF ME

After a period in which I refrained from commenting on emerging discussions, my first posts in the Bulsa Facebook group caused something of a stir, with some asking, ‘Who is this participant?’ or ‘Is he a Bulsa?’

I.N.A.: Hi Sir, I have noticed how immensely you contribute to every discussion and thing related to Buluk. Sorry to ask, but are you a Builsa? I’m asking this because of your colour […].

However, the vast majority of members welcomed me warmly. Scepticism about accepting an outsider into a purely Bulsa group was not expressed in writing, even if it may have been present in some people. As such, even if I publish below predominantly critical or even negative contributions to my position, their small number is disproportionate to the large number of approving comments and expressions of thanks.

I had already experienced a sceptical attitude towards the work of European ethnologists and linguists before participating in a Facebook group. When I gave the late, educated Kadema chief a copy of my Buli-English Dictionary (Kröger 1992), he replied: ‘Why can’t something like this be written by a Bulsa?’

In the Bulsa Facebook groups, similar but harsher comments were made by individuals. When I uploaded a photo of a mat-ordeal (noai boka) in a discussion on commemorations of the dead [endnote 12], I received the following comment:

A.M.A.: Pl[ease]. and pl [ease] somethings are there which is not good for internation veiw. you can talk about them but not postion of pic. less respect our culture.

A.B.F. [female]: Pls it is our culture u can’t go n take pic of our culture n display on face Bork it dus not concern u.

A.B.: A.M.A. and A.F., how much of your culture do you know? How many distortions haven’t been made? Who is documenting the true culture of Buluk? Let’s exercise circumspection when criticising someone. Franz Kröger has dedicated so much of his life documenting our culture and all you come here to do is talk about respect. When was the last time any of you thought about preserving our culture? This is one of the ways to preserve it.

Significantly, I rarely had to defend myself against such accusations because this was immediately done by another participant (in this case, a director of a Ghanaian television company).

When a Bulsa from Sandema uploaded a list of Kanjaga chiefs I had compiled and published in the Buluk Kaniak magazine (2012), critical remarks about its content followed.

E.S.A.: So many errors in relation to KANJARGA !! I’m gutted.

A.L.A.: False history.

L.A.: […] I think this is below the belt. Mr Franz Kröger is trying so hard to help build our history, we can only help him by trying to fill gaps in his research.

E.S.A.: Prof. [endnote 13] Franz Kroger’s accounts of southern Builsa chiefs isn’t reliable since he never conducted any research in the area. In fact, I will prefer Rattray’s account [endnote 14] since he had the opportunity of interviewing my great grandfather Naab Anyatuik (who was the chief at that time). Albeit, I have my own reservation about Rattray’s account!!!

F.K.: It is not true that I never conducted any research in the area. In 14 stays between 1973 and 2011, I did research among the Bulsa, altogether it was nearly 5 years. We can only find historical truth by comparing different results and statements […].

A.L.A.: Franz Kröger is an anthropologist. His work is credible. He is not a historian. So his perspective is not history. I guess his work has always been focused on a better understanding of our society and culture. Our history is actually not yet written […].

C.R.Z.: Prof. Franz Kröger please don’t worry yourself over people who sit in their own rooms and dream about what the history of Buluk should be. We will only engage in analyzing empirical papers. If anyone has such, he should publish for us to read. Until then we consider all other views as mere opinions devoid of any intellectual integrity. We can not be hoodwinked into discussing fiction. Until there is contrary intellectual discourse backed by hardcore evidence, prof. Kroger’s work remains relevant.

A.L.A.: No one has ever said the prof work is not relevant. It is not history of Buluk. I am a citizen. I don’t think that anyone will know my own history better than me. As an anthropologist as he is I value his work. He lived with our people, created trust and did his work not as a Bulsa historian but to understand our culture. In any case, renowned African historians like Ali Mazuri and Adu Boahen have had good reason to dispute European perspective of African history [endnote 15].

Here, the participant has arrived at the abovementioned view that Europeans are not qualified to write about African history. The participant also expressed the same opinion in other Facebook discussions.

A.L.A.: All attempts by Europeans to write our history for us must be disregarded. I am a student of Buluk History of the Rev James Agalik. It must be disregarded. False history must be stopped […]. Some Europeans came pandering to false views of chiefs. Some did a dirty job to protect some integrity. They got that funding to falsify our history […] No one can come from Europe or America telling a Bulsa that he knows your [his] history better than you [he?]. Such people are the new invaders. The mission is to conceal facts.

L.A.: Mind you, the whites that came to Ghana in this case to record history as they were told, were not doing so to satisfy any traditional leader […]. Give them some credit regardless your personal dislike for them.

CONCLUSION: ARE BULSA FACEBOOK GROUPS WORTH RESEARCHING?

Facebook groups do not belong to the classical research objects of anthropologists, and the methods one uses in anthropological research must be adapted to this new object.

Even if the classic methods of anthropology – participant observation and interviews – can still be applied to a certain extent, they must be adapted to the new subject matter. For example, although photos are sometimes uploaded to the discussion texts, in the study of Facebook groups, ‘observation’ primarily refers to the content of texts embedded in a dialogue or discussion. The ethnologist usually knows nothing or very little about the other persons, about their appearance, age, education, profession, or location. More data about the participants can be viewed on their Facebook profiles, but unfortunately, many participants provided no or only very incomplete information in the questionnaire.

As a research method, the interview has also undergone a major transformation in the context of work with Facebook groups. Often, a participant (in my case, it was rarely the ethnologist) asks a question and receives various answers, some of which are irrelevant to the topic. The result is usually not a dialogue with one questioner but discussions that lead to more and more topics, with one leading to the next. There is no discussion leader, and the original question is often completely forgotten in all the digressions.

Despite these limitations, I assume that the activity in these groups carries meaning and benefits the indigenous participants as well as the ethnologist. The activities in the group are intended to strengthen the sense of belonging to the educated elite and establish their self-image within the traditional culture. Many participants already knew each other and their degree of kinship to others before joining the group; the interlocutors were often addressed as ‘brother’, ‘sister’ or ‘uncle’ if there was no closer relationship. Nevertheless, the desired goal of strengthening friendships with one another is not always achieved, as arguments between South Bulsa representatives and the numerous family members of the Sandemnaab, in particular, can sometimes be very contentious and even border on insulting. However, a member of another family usually intervenes as a mediator and reminds people of the unity of all Bulsa by posting, for example, the often-quoted Bulsa proverb, ‘Zurugaluu lam kan be’ (freely translated: ‘unity makes strength’).

In addition to bolstering the participants’ self-image and sense of togetherness, the Bulsa Facebook groups increase their knowledge of their culture and language, filling in any gaps. After a discussion about customs and rites, Bulsa history, the meaning of Buli words, and the possible translations of modern English terms into their Buli equivalent, laudatory reviews often appear from people uninvolved in the conversation who express their great interest in the topics discussed and remark on their lack of knowledge about specific issues.

A.E.A.: Cl. Ak., this is so illuminating. Thanks.

A.A.: These are the issues that make the group interesting.

D.A.: Well, I doff my hat.

E.Sh.A. [female]: Thumbs up to all of you, wonderful arguments. I enjoy everyone bid of your comments […].

F.L.: I have been in the background enjoying the debate though.

S.S.S.: Voila! This is elephant meat.

A.D.G. [female?]: Am learning so many things today.

P.A.: Thanks for the information and sharing of the pix.

It seems that individual elements of Bulsa culture need to be analysed in terms of their value or lack of value for today’s society, reducing traditional culture into an acceptable form for educated people. Customs such as FGM, scarifications, or the use of violence when taking a bride home (‘bride kidnapping’) are rejected by a vast majority of the educated population, and efforts are being made to eliminate them from the culture. Other topics, such as participation in funeral celebrations, are still up for debate, and attitudes remain in favour of and against it even after Facebook discussions.

In addition, my experience exemplifies how passive or active participation can be worthwhile for ethnologists. Although it was claimed above that participants’ knowledge of their culture is usually very limited, notable exceptions did occur. Some participants presented their knowledge in unusually long contributions, providing considerable detail.

If an ethnologist wants to make enquiries in the compounds about topics considered secret knowledge, a willing elder may be interrupted by a younger resident with a school education and reminded of the secrecy. Such reticence has generally disappeared among the members of the Facebook group, who are well-versed in traditional matters [endnote 16]. They are not regarded as a bumbobro (traitor; someone who passes on secret knowledge) by the other participants but are praised and admired for their extensive knowledge (see above).

Aside from the critical exceptions outlined above, the participating ethnologist’s data, images, quotations based on field notes, archival work, and publications were highly praised.

L.A.A.: Woow prof your are indeed a Bulsa even if you’re German.

A.J.T.: Thanks Prof. We are grateful for sharing this knowledge with us.

D.A.: Thank you Dr for a wonderful work done.

G.A.: Thanks Dr. Kroger, for your continues contribution on Builsa history.

For the European ethnologist, there is certainly the possibility of supplementing data collected in field research by a social media-based group or learning completely new facts from parts of Bulsaland that he has given less consideration to during visits. Occasionally, however, I did not ask a knowledgeable participant for further details in front of the whole group but wrote to him in a letter as a private message, hoping that he would share his knowledge more freely there than in front of the whole group that included opponents.

My desire to get to know the educated Bulsa elite more closely according to their worldview, their knowledge of their own culture, and their relationship with each other and with the traditional authorities (chiefs, elders, earth priests, heads of compounds) has been satisfactorily fulfilled by my participation in discussions in two Bulsa Facebook groups over the past decade or so. These discussions also illustrate how important feedback from the representatives of the culture being researched is to the researcher and how gratefully this willingness to share and discuss cultural topics is received.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AKANLIG-PARE, George

2020 ‘Palatalisation in Central Buli’, Legon Journal of the Humanities 31(2):66–94

AKANDZENAAM, Linus Angabe

2013 ‘Our Forgotten Heroine – Lydia Azuelie Akanbodiipo’, Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and History, 7:67–68

APEN, Mathias

2015 ‘Origin and History: The Feok festival of the people of Buluk’, Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and History 6:107–112

ASIANAB AFOKO, Francis

1970 The Ayietas. Bolgatanga [unpublished manuscript]

BLANC, ULRIKE

2000 Musik und Tod bei den Bulsa (Nordghana). Münster, Hamburg, London: Lit

DUPERRAY, Anne-Marie

1984 Les Gourounsi de Haute-Volta. Conquête et colonisation 1896–1933. Studien zur Kulturkunde, vol. 72, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden GMBH

ETHNOLOGUE, LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD

2021 ‘Kantosi’. Ethnologue, languages of the world. Dallas (Texas) SIL International. http://www.ethnologue.com/bwu [accessed on 9 November 2021]

GRABENHEINRICH, MIRIAM and SABINE KLOCKE-DAFFA

2005 15 women and 8 ancestors. Life and Beliefs of the Bulsa in Northern Ghana. Münster: Institute of Ethnology [Handbook of the Bulsa Exhibition 2005]

KLOCKE-DAFFA, SABINE

2015 ‘My dad has 15 wives and 8 ancestors to care for. Conveying anthropological knowledge to children and adolescents’, in Elisabeth Tauber and Dorothy Zinn (eds.), The public value of anthropology: Engaging critical social issues through ethnography, 61–80. Bozen/Bolzano: Bolzano University Press

KRÖGER, Franz

1978 Übergamgsriten im Wandel. Kindheit, Reife und Heirat bei den Bulsa in Nord-Ghana. Kulturanthropologische Studien, edited by R. Schott and G. Wiegelmann, vol. 1 Hohenschäftlarn near Munich: Kommissionsverlag Klaus Renner

1992 Buli-English Dictionary: with an introduction into Buli grammar and an index English-Buli. Münster and Hamburg: Lit

1997 ‘Brautraub? – Ein Beispiel aus Nordghana’, in: Ursula Bertels, Sabine Eylert, Christiana Lütkes (eds.), Mutterbruder und Kreuzcousine – Einblicke in das Familienleben fremder Kulturen, 35–40. Münster, New York, Munich, and Berlin: Waxmann

2008 ‘Raids and refuge: The Bulsa in Babatu’s slave wars’, Research Review, N.S. 24(2):25–38, Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana

2013 ‘Who was this Atuga? Facts and theories on the origin of the Bulsa’, Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and History 7:69–88

2015 ‘BMY [Bulubisa Meina Yeri], description and analysis of a Bulsa Facebook group’, Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and History 8:52–62

2017a ‘History of the Bulsa – with special consideration of the slave wars’, Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and History, Special Issue. https://buluk.de/new/?page_id=2376 [accessed on 9 November 2021]

2017b ‘Southern and Northern Bulsa. Co-operation and competition’, Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and History, 10:30–35

KRÖGER, Franz (ed.)

2018 ‘Discussions in the Facebook group Buluk Kaniak’, Buluk – Journal of Bulsa Culture and History 11:18–36

MEIER, Barbara

1993 Doglientiri. Frauengemeischaften in westafrikanischen Verwandtschaftssystemen, dargestellt am Beispiel der Bulsa in Nordghana. Münster und Hamburg: Lit

1997 ‘Kinderpflegschaft und Adoption in Ghana: Die kleinen Ehefrauen der Bulsa’, in: Ursula Bertels, Sabine Eylert and Christiana Lütkes (eds.), Mutterbruder und Kreuzcousine. Einblicke in das Familienleben fremder Kulturen, 85–95. Münster, New York, München, Berlin: Waxmann

1999 ‘Doglientiri: an institutionalised relationship between women and its social implications among the Bulsa of Northern Ghana’, Africa 69 (1): 87–107

PERRAULT, P.

1954 History of the tribes of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast. Navrongo: St. John Bosco’s Press (unpublished manuscript)

RATTRAY, Robert S.

1932 The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland, 2 vols, Oxford: Clarendon Press

SCHOTT, Rüdiger

1977 ‘Sources for a history of the Bulsa in Northern Ghana’, Paideuma 23:141–168

STRIEWISCH, Martin

1988 Die Bedeutung des Hirsebrauens für die wirtschaftliche und soziale Stellung der Frau in westafrikanischen Gesellschaften. Münster [unpublished manuscript]

WILKS, Ivor

1989 Wa and the Wala: Islam and polity in northwestern Ghana. New York, New Rochelle, Melbourne, and Sidney: Cambridge University Press

ENDNOTES

1 The participants consisted of males and females.

2 The participants’ education levels can be partly inferred by assessing their English proficiency. As such, the contributions quoted in this paper have not been grammatically or stylistically corrected.

3 Although the discussion partners have published their opinions on the Internet with their full name, I consider a limited anonymisation of proper names to be appropriate.

4 Only heads of compounds (yeri nyam) have the right to vote in the election of a Bulsa chief.

5 Kröger 1978:258–281 and 1997.

6 This practice, called doglientiri, has been extensively described by B. Meier (1993, 1997 and 1999).

7 See B. Meier 1993, 1997 and 1999.

8 Other contributions from female participants often only signal agreement or interest, with responses like ‘Thank you for the information’ or ‘Very interesting!’ or the individual simply clicking the ‘like’ symbol. Since the Bulsa practise a virilocal marriage system and young women often leave their parents’ compound early in life, it is more difficult for them to gain in-depth knowledge about their ancestral family’s cultural characteristics and history. In the compound that a woman marries into, care is usually taken to ensure that foreign women do not learn any ‘secrets’ from within the compound.

9 See also Schott 1977 and Kröger 2017a.

10 Chuchuliga, located in the north-east of Bulsaland, belongs to the Bulsa North District. The Kasena have significcantly influenced this village, which has strong economic ties with Navrongo. Akanlig-Pare (2020) has found that, strangely enough, the Chuchuliga dialect is more closely related to the one spoken by the South Bulsa than the North Bulsa.

11 A verbatim copy of the three documents can be found in Buluk 13 (2020):17–24.

12 The blame for the death of the deceased is determined in a mat-ordeal. The photo showed two men carrying the mat on which the deceased had died. I was surprised by the adverse reaction; some Bulsa probably do not want an outsider to take a closer look at the traditional religion, especially not to illustrate it with photos, even if others consider this type of documentation important.

13 I have pointed out several times in vain that I do not hold the title of professor. The PhD titles of other participants are usually omitted from the discussion.

14 R.S. Rattray (1932).

15 Ali Mazrui [not Mazuri], the author of various political publications, was born in Kenya in 1933 and died in New York in 2012. His call for nuclear weapons to be supplied to African states caused a great public stir. Albert Adu Boahen (1932–2006) was a Ghanaian historian who ran unsuccessfully for president in 1992. It is unclear which of these academics’ numerous publications the Facebook author refers to.

16 The phenomenon that one may be likelier to reveal insider knowledge to a stranger than, for example, people to whom one is distantly related is also something I encountered several times during my field research. Indeed, when I wanted to obtain information from older men who were usually very willing to talk, I was refused any information one morning because I was accompanied by a young man from the chief’s compound.

- The Permanent Establishment of Ritual Deviations (German original version 2012)

- Bulsa Rites of Passage (English Version)

- Title, Contents and Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter I: Pregnancy

- Chapter II: Birth

- Chapter III: The Guardian Spirit, Naming and Names

- Chapter IV: Scarifications

- Chapter V: Wen Rites

- Chapter VI: Excision and Circumcision

- Chapter VII: Courting and Marriage

- Chapter VIII: Death and Burial

- Chapter VIII (contd.): Funeral Celebrations

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Übergangsriten im Wandel, Deutsche Version (1978)

- Titel, Vorwort, Inhalt, Einleitung

- Schwangerschaft und Geburt

- Namensgebung und Namen

- Skarifizierungen

- Wen-Riten

- Beschneidungen

- Brautwerbung und Ehe

- Tod, Trauer und Bestattung (1. Teil)

- Tod und Bestattung (2.Teil)

- Die Kumsa Totenfeier

- Die Juka Totenfeier

- Schluss

- Anhang

- Literaturverzeichnis

- Gesamtedition der Übergangsriten

- Buli Language Guide (2020)

- Buli Names

- The Bulsa Educational Elite… Discussions in a Facebook Group (German original version 2022)

- The English and American Image of Germany in the Past

- The Ritual Calendar of the Bulsa (German original version 1986)

- Evil in the Divine Being (German original version 2013)

- Black Crosses and Divinatory Objects (German original version 1992)

- Traditional and School-Based Education among the Bulsa

- Bulsa Divination und Wahrsager

- Historical Sources