Adapted and translated from the journal Anthropos 81, 1986: 671–681.

The photos were taken between 1973 and 2011, and were inserted into the text in 2025. Parentheses such as [p. 672] refer to page numbers in the original German version.

The Ritual Calendar of the Bulsa (Northern Ghana)

1. Concept and division of time

‘You count the cattle, but not the people’. This was the negative response of my main informant, L. Amoak, when I wanted to carry out a census in certain households belonging to his kinship group. Even in a temporal context, the Bulsa, like most of their neighbours, show a clear reluctance to associate people or human existence with numbers. Until a few decades ago, counting years of life was little known, and even today, many Bulsa do not consider it necessary to write down or have others write down the birthdates of their children. Nonetheless, they are familiar with the number series up to over one thousand, and Buli, the language [p. 672] of the Bulsa, is extremely rich in temporal adverbs that offer precise differentiation.

Time indications that refer to the present time unit or one or two time units away from it are usually expressed by a single temporal adverb: today: jinla; yesterday: diem; the day before yesterday: daam pa te diem; a few days ago: daam; tomorrow: chum; the day after tomorrow: vonung; on a later day in the future: dadidai or dayong; this year: donla; last year: diim; next year: bali; in two years: bali di choa (literally: ‘the companion of the coming year’). Numerals can also be easily combined with temporal terms to indicate time, such as ‘three days ago’, daa ngata ngai le taam la (literally: ‘days three, which are over’).

Although some idiomatic expressions in Buli can be translated by including the word ‘time’, such as n ka nina, ‘I have no time’ (literally: ‘I have no eyes’, i.e. my attention is focused on something else), it is notable that there is no direct equivalent in Buli for the abstract term ‘time’. Only recently has the English word ‘time’ (Buli pronunciation tam, definite form tamwa) entered the language as a loanword, as there was obviously a need for such a term. Today, tam is not only used by those Bulsa who know English; even illiterate people have incorporated it into their vocabulary. Tam is the time that can be measured by a clock (or gogo, to use the loanword from Hausa, in folk etymology also explained as English go! go!); tam continues to run even when meaningfully occupied, psychologically experienced time stops, such as at night during sleep. In tam, the concept of time has taken on a linear quality that was less familiar to the consciousness of the individual before contact with European culture. In the traditional view of the Bulsa, time is understood cyclically. This becomes strikingly evident in attempts to measure short periods of time. While our calendar clocks, with the addition of the year, are used to categorise even very brief periods according to a linear time sequence, the Bulsa, as is generally the case with measurements on a circle, indicate time by an angle. If, for example, a householder leaving his compound wishes to indicate to his neighbours that he will be back in two to three hours, he raises his right arm in the direction in which the Sun will be found after this passage of time. In particular, the Sun’s zenith, and thus the time of midday, can be determined very precisely using this method. Another way of measuring the time of day corresponds to the principle of the sundial. A group of older men can arrange to meet later in the day, for example: to determine the time, one uses a stick to draw a line on the ground where he assumes the shadow of the compound wall, which is of approximately the same height in the various compounds, will be at the time of the intended meeting. Both types of measurement described here work even if the Sun casts no visible shadow. To a greater extent than by these methods, however, the day, the smallest temporal cycle, is divided into different phases by recurring activities (meals, field work, housework, evening discussions, etc.). [Addition 2025: The collection of termite soil for the chickens (miedi), which takes place shortly after sunrise, before breakfast, is particularly popular as a temporal reference.]

The next cycle in terms of length is the market cycle. Every three days (in Fumbisi every six days), a market takes place in most Bulsa villages. Since market days fall on different, often consecutive days of the week, especially in neighbouring villages (Heermann 1981: 136), they can be used for a more precise range of time calculation than the length of the cycle suggests. One might say, for example, ‘I will visit you one day after the next Kadema market’. Ritually, market days do not play a major role. I have heard that sacrifices should not be made on market days, as the recipients of such offerings like to spend time at the market, but this rule is not taken very seriously and is unknown to many Bulsa.

The seven days of the week (bakoai, Hausa loanword) are known among the Bulsa, as among many other ethnic groups in West Africa, by originally Arabic names (from Monday to Sunday: Tani, Talaata, Lariba, Lamisi, Azuma, Asibi, Laadi). [p. 673] Although these are often used as call names for children born on the respective days of the week, they can never be chosen as names for ritual naming (segrika; cf. Kröger 1978: 108). Nor are taboos for particular rites or activities associated with certain days of the week, as is the case in other parts of West Africa. Indeed, most illiterate Bulsa farmers are unlikely to know which day of the week it is on any given day.

The lunar cycle and its phases play only a minor role in the time consciousness of the Bulsa, although terms exist for ‘half moon’ (chiik kauk, literally: ‘moon half’), ‘waxing moon’ (chiik buli, literally: ‘young moon’) and ‘waning moon’ (chiik kpak, literally: ‘old moon’). In some of these terms, as in the sayings that the old moon dies before the new moon (chiik kum, ‘death of the moon’) and that a new moon is born shortly afterwards, there appear linguistic echoes of the human life cycle. This also applies to the more precise names of the phases, such as when the full moon is said to be fifteen days old (chiika ta ka da pi ale nganu jinla). Nevertheless, genuine personification of the moon is not common in other areas of the region.

Chiik amulet

As far as I am aware, only the day of the new moon is ritually significant and taboo for certain activities. For example, no guinea fowl eggs should be laid under chickens on this day, and no millet should be sown (information from Sandema-Kobdem). The birth of a child on the day of the new moon has more far-reaching ritual consequences, as this creates a close interrelationship between the child and the moon. Parents will hang an iron moon amulet around the neck of such a child, and as soon as the child is able to speak, on every new moon (or, based on other information, one day after the new moon), he or she should climb onto the flat roof of the house and blow ashes towards the moon three times (if male) or four times (if female). The child should then say: ‘Chiik a baling-bo, N.N. a bii-yo’ (‘The moon becomes thinner, N.N. [the child] becomes thicker’). Without this ritual, called pobsika, it is said that the child will always be weak or sickly.

Apart from the lunar and solar cycles, to my knowledge, the Bulsa know the movements of only one constellation in detail, which they call chiisa nuru (chick man) or chiisa ma (chick mother). This consists of a cluster of several stars that are difficult to identify (difficult to count, ‘like young chicks’). The Pleiades – the scientific name of the chiisa nuru – do not appear in the night sky for a period corresponding approximately to the month of May, as their rising and setting times during that period roughly coincide with those of the Sun. The early millet (naara) should be sown before the disappearance of the Pleiades from the evening sky; soon after their reappearance in the early morning sky, the early crops should be in bloom.

The counting of the cycles listed so far and combinations of smaller and larger cycles (weeks per month, months per year, etc.) are unknown in the traditional calendar of the Bulsa, although there have been some attempts in recent times to find Buli equivalents for the English month names:

January: ngoota chiik (cold moon or cold month);

February: gunggona chiik (hourglass drum month, i.e. month of funeral ceremonies);

March: vaala chiik (month of the empty millet stalks, rubbish, weeds; the fields are prepared for sowing during this time);

April: sambula chiik (month of the red dawadawa blossoms);

May: borik chiik (sowing month);

June: kpari chiik (weeding month);

July: naara chiik (month of the early millet);

August: za paala bogluta chiik (month of the early millet sacrifice);

September: chaung chiik (month of chaung weeding);

October: sungkpaata chiik (groundnut month);

November: za cheka chiik (millet harvest month);

December: fanoai chiik (month of harvest sacrifices) or burinya chiik (Christmas month).

2. The solar cycle: Agriculture and rites

[p. 674] The above remarks on the shorter temporal cycles may have shown that – apart, perhaps, from the daily cycle – these have no great significance for the religious and ritual life of the Bulsa. The rhythm of peasant life, with all its ritual accompaniments, is largely determined by the annual solar cycle. Cosmic events, however, have only an indirect influence on ritual activities, that is, only insofar as they cause changes in vegetation or create the conditions for certain agricultural activities. The two annual solstices and the relatively small variations in the length of day and night across the year are not accompanied by any ritual acts; most Bulsa are not even aware of them. The first rainfall, similarly, does not result in any associated sacrifices or rites.

The two major seasons, the rainy season (yuei) and the dry season (wen-karik), are subdivided according to farming and ritual activities (for more details, see Kröger 1978: 4). After the last harvest has been brought in, the Bulsa year ends with the great harvest sacrifices (fanoai bogluta) sometime in December, and the new year begins at the same point.

In the dry season that follows, field work largely comes to a standstill, apart from preparations for the coming rainy season and the planting of artificially irrigated gardens. The dry season is the period of rites that are not dependent on annual events but on the human life cycle, which van Gennep (1909) categorises as rites of passage. Most of these can be performed at any time of the year, but only in the dry season are two important conditions met for all Bulsa: full storehouses make it possible to feed many guests, and the pausing of labour in the fields creates free time. These are accompanied by some favourable climatic conditions. Female circumcisions (in the form of clitoridectomies) are often carried out in the cool morning hours of December. The dry season is also particularly suitable for the wen-piirika, the erection of a first personal shrine (Kröger 1978, 1982), as the decisive ritual act, the pressing of a stone into a ball of clay, should only be carried out at sunrise in visual contact with the Sun. Although weddings take place all year round, they are probably also more frequent in the dry season; only in recent times, there has also been a second peak in September following the end of the school year. Funeral ceremonies lasting several days, which often take place several years after the burial of the deceased and attract a large number of visitors, are often held in the very dry months of January, February and March.

The end of the dry season is not only a time for agricultural preparations for the anticipated sowing period, such as hoeing or, more recently, ploughing the fields; ritual preparations must also be made for the onset of the first rains and the subsequent sowing. While the household constitutes the ritual unit for almost all rites associated with agricultural activities, the ritual acts intended to secure the first rains extend not only beyond the household community but even beyond the Bulsa tribal organisation.

Tongo mobile shrines. Left: the shrine that remains in the Bulsa compound; right (calabash): the shrine brought by the Tallensi

Before the onset of the first rain showers, small groups of Tallensi (from the area south of Bolgatanga, northern Ghana; cf. Fortes 1936, 1945) come to the Bulsa area to perform certain ritual acts. According to most reports, they appear after the organisation of their Galago festival (cf. Rattray 1932: 358; Riehl 1993) in February to April. These Tallensi groups of three to four men each come from different clan sections, but all seem to somehow represent Ngiak, the large Tongo shrine. The clan sectiony of Yinduuri and Tenzuk probably play a greater role than Shia, Sapaat and Buuni. It was possible to obtain details from the old men of Tongo-Tenzuk and Yinduuri. Both clan sections send a delegation to Bulsaland twice a year for around three weeks at a time, once between February and May and once in October/November. I have not yet heard anything from the Bulsa, however, about Tallensi sacrifices in October/November. The Tenzuk [p. 675] group moves via Sandema, where its members apparently do not sacrifice, to Kadema (sacrifices in five compounds; first sacrifice in Ayaribil Yeri), Wiaga (over twenty compounds), Siniensi (about ten compounds), Gbedema (four compounds) and Kanjaga (about ten compounds). They call this route the Kanbangre route. The route of the Yinduuri group progresses via Kadema, Wiaga, Siniensi, Doninga, Wiaga, Kanjaga, Kunkoak and Gbedema (Naa-kpak Yeri). The Tenzuk group sacrifices in the Bulsa compounds exclusively to its own shrine, which the delegates bring with them from Tongo. According to a Bulsa informant, this consists of earth from the large Tongo shrine, which is transported in a calabash or clay bowl balanced on the head. According to R. Schott (unpublished field notes, 5 March 1967), this shrine consists of a calabash, which also receives the offerings, and a black goatskin closed with strings, in which smaller offering-gifts, such as money and hoe blades, are placed.

All sacrificial animals are either provided by the Bulsa or fetched by the Tallensi, unchallenged, from their Bulsa pasture. The guests also receive live animals, which they take back to their home village. Not all of these are used for sacrificial purposes, as donkeys are also mentioned as offerings alongside sacrificial animals (cattle, sheep, goats, chickens, etc.). In most cases, the reason behind these ritual tributes can be traced back to a vow made by a Bulsa ancestor who once promised the Tongo sanctuary a sacrificial animal or other gifts for all time to come if, for example, he was granted a wealth of children or good harvests.

While the Tenzuk groups only make offerings to their own shrine, the Yinduuri people also offer to Bulsa shrines, which can be described as ‘offshoots’ of the Tongo shrine. In Gbedema-Goluk, in the compound of the former chief (Naa-kpak Yeri), the centrepiece of such a shrine consists of a covered calabash said to contain some earth from the Tongo shrine. In the same roundhouse (dok), which one may only enter without shoes and with one’s upper body bare, there is also an object that looks like a large horn wrapped in a sheepskin. It hangs on a wall and must never come into contact with the ground, or it will never rain again.

When the Tallensi appear in March/April, each of the four clan sections of Gbedema sends a sheep by way of its earth priest (teng-nyono), and another is provided by the Naa-kpak Yeri compound. These sheep are usually taken to Tongo alive, but one or two may also be sacrificed to the shrine in Gbedema.

Not all Bulsa clan sections maintain ritual contact with the Tongo sanctuary. In Sandema, the Kobdem clan section is responsible for the rain. The rainmaker (ngmoruk-yaaro), who used to wear a red cap like a chief or a diviner, goes, according to R. Schott (unpublished field notes, 28 February 1967), to the sacrificial altar of the rain shrine with dry millet flour in a calabash, before the first rains begin, and says: ‘I want to sacrifice this flour to you, but I have no water to pour on the flour. You know where you can get water to pour on the flour’. He then leaves the calabash and millet flour on the altar and completes the millet water sacrifice later, when the rains come.

Kobdem has no connection with Tongo; there even seems to be a certain rivalry between them. Neither Sandema-Fiisa, where Azakzuk, the most important earth sanctuary (tanggbain, pl. tanggbana) of Sandema, is located, nor Wiaga-Badomsa and Yimonsa have a ritual relationship with Tongo, as their own tanggbana are similarly responsible for the fertility of the fields.

Some clan sections have connections to Tongo as well as to local ‘rain gods’. In Sandema-Kalijiisa, at the end of the dry season, the elders (kpaga, sing. kpagi) of the lineage segments gather in the house of the earth priest (teng-nyono). Each brings a hoe, and these are later presented to the Tallensi when they come to the house of the teng-nyono. No sacrifices take place here. If the rains [p. 676] then fail to come, especially if the second rain shower is delayed, the Kalijiisa elders gather again, and a delegation led by the teng-nyono is sent to Kobdem to ask the local ‘rain god’ for more rainfall.

An informant from Sandema reports that the first rains often come just as the Tallensi begin their journey home. Before departing, they often leave instructions as to when the first sowing should take place. The early seed is usually mixed shortly after the first, second or third rain shower. It typically consists of early millet (naara), guinea corn (za-monta), late millet (za-piela), beans (tue) and a type of pumpkin (buura, also called neri or agusi). Before some women (e.g. of one household) plant four to five seeds in holes dug by the men with planting sticks, certain sacrifices must be made, and from then on, every important agricultural activity is accompanied by corresponding sacrifices. The sacrificer is usually the head of the compound (yeri-nyono), and the sacrificial community is usually the compound, although guests may be invited to some sacrifices.

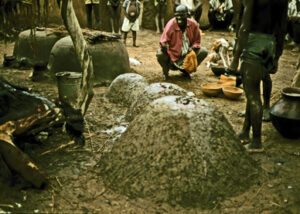

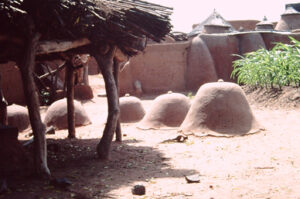

Ancestral Shrines in front of Adeween Yeri

In the below description of the sacrifices, it will often be said that all the shrines of the compound receive a certain sacrifice. The number and type of these deities varies from compound to compound, depending mainly on the number of kinship groups in the compound and the seniority of the head of the compound within their lineage group.

For the rather small compound of Adeween Yeri (Wiaga-Badomsa), in which only the widow of Atiim lives with her two sons, but to which my informant L. Amoak, who lives in the centre of Wiaga, and his family also belong in ritual terms, all of the household deities to whom offerings are made at seed and harvest sacrifices are listed here. There are thirty-eight recipients of offerings in twenty-two different shrines, listed below:

1) Asik (L. Amoak’s father), with two medicine pots (tiim-bogluta), which also receive part of the sacrificial food;

2) Adeween (Amoak’s FaFa), with another sacrificial stone for Adeween’s childless brother, Ageng, and a medicine pot;

3) Adaachoruk (Amoak’s FaFaFaBr), with another sacrificial stone for Adaachoruk’s brother;

4) Agbana (Amoak’s FaFaFa);

5) Ayarik (Amoak’s FaFaFaFa).

Shrines 1–5 are located in front of the compound. They are shaped like mounds with round sacrificial stones (one stone per ancestor).

6) Abonwari (Amoak’s FaBr): as his funeral ceremony has not yet been held, his shrine stands in an inner courtyard;

7) Amoak’s FaMoMo: a pot filled with earth (ma-bage; cf. Kröger 1978: 169 ff., 1982: 22 ff.);

The three knobbed ma-baga of Adeween Yeri

8) Amoak’s FaFaMoMo (ma-bage);

9) Amoak’s FaFaFaMoMo (ma-bage);

10) Amoak’s FaFaFaBrMoMo (ma-bage);

11) Amoak’s FaFaFaFaMoMo (ma-bage);

12) Teng: earth from Badomsa’s tanggbain (earth shrine) in two cow horns;

13) Nipok-tiim: two medicine pots to prevent wives from running away; four sacrificial spots;

14) Jadok-yiuk (lizard deity) on the flat roof of a house; three sacrificial spots;

15) A light-coloured stone and two clay pots (nothing more is known about the significance of this shrine);

16) Atiim’s divination shrine in front of the compound; five sacrificial spots;

17) Chameleon relief (bunoruk) on a granary (like 14, 16 and perhaps also 15: jadok deity);

18) Amoak’s and Atiim’s mother and her mother: stones on a footpath leading towards Amoak’s and Atiim’s mother’s parents’ compound;

19) Atiim: mound with a stone in the courtyard;

20) Ayomo (Atiim’s second youngest son): personal shrine (Ayomo also offers sacrifices to 1–19);

21) L. Amoak: personal shrine (Amoak sacrifices);

22) Tanggbain: earth shrine (group of rocks) about 200 metres east of the compound (Ayomo sacrifices).

The series of sacrifices always begins with the most important male ancestors in front of the compound. [p. 677] The order of the other sacrifices does not seem to be exactly fixed, as I was able to convince myself by comparing several harvest sacrifices performed in the same compound (1974, 1978, 1979). Groups of sacrificial shrines that are regarded as a single unit (1–2, 3–5, 7–8, 9–11) receive their libations from the contents of a single sacrificial calabash; for all other sacrifices, the calabash is filled again from a large clay pot. After the sacrifice, the members of the sacrificial group (in this case, Ayomo Atiim as the sacrificer, L. Amoak as the officiant of the sacrificial ritual and I) drink the rest of the millet water. When the sacrifice is to a personal shrine of a living person (20–21), only the owner of that shrine can drink the rest of the potion, and Shrine 15 does not allow anyone present to partake of the sacrificial potion; the entire contents of the sacrificial calabash are poured over the shrine.

In the following, the rites and sacrifices conducted, which are closely linked to agricultural activities, are presented in chronological order.

1) Zabuura-nyiam-bogta (zabuura: mixture of different seeds, including early millet, late millet, beans, pumpkin; nyiam: water; bogta, short for bogluta: shrines, sacrificial spots. Kaabka, ‘sacrifice’, should be added to all the sacrificial names listed here; however, it is usually omitted).

Before the early millet and other crops are sown at the end of April or in May, a few cobs of early millet are taken from the seed storage basket (yikoari) or a freely hanging bundle of millet cobs. All of the deities of the house receive an offering from these cobs in the form of millet water. In Sandema, I was told that such offerings are not held in all houses, but my research revealed that seed offerings are common in all parts of Bulsaland.

Women sowing seeds

The mixed seeds in the big busik-basket with a small seed calabash

From immediately after sowing until the early millet is harvested, girls and young women beat kayagsa stick rattles in rhythmic variations. These consist of about a hundred round calabash discs with a diameter of 2–5 cm, with holes in the middle, [p. 677] strung on a thin stick. I could not clearly determine whether there is a sacred idea behind this custom or whether practical purposes, such as scaring birds away from the millet fields (information from Wiaga), are behind it. Today, practitioners know of no other reason for the temporal restriction on this activity than that it has always been this way. The strongest motive for the girls to engage is the joy of rhythmic play. In groups of two to four girls, a rhythmic dialogue may develop among the members, in which a certain rhythmic response is given to particular rhythmic patterns. Simple verbal messages can allegedly be conveyed through the stick rattles.

Girl shaking the kayagsa

Other types of noise, especially drumming, dancing and the firing of guns, are to be avoided, particularly during the final ripening phase of the early millet, as they can cause storms that damage the harvest. Among the neighbouring Kassena tribe, this commandment of ritual silence also (or only?) applies to the late millet (information provided by R. Schott).

2) Ti-loansi-tuita-bogta (name difficult to explain; loansi: sowing by scattering; tuita: bean leaves).

Before the early millet is harvested, the leaves of the bean plants and the pumpkin-like fruits of the buura, which were sown together with it, can be harvested. Bean leaves (tuita) and buura seeds are used as ingredients for soups. Before these are eaten for the first time, all of the compound shrines must receive them as offerings. A soup is made from the bean leaves, together with other ingredients. The buura seeds are pounded and formed into small balls (kukula). In the late afternoon, the bean leaf soup is offered to all of the shrines, after which some of the kukula balls are pressed onto the sacrificial spots. An informant from Sandema-Kobdem describes the bean leaf sacrifices as obligatory and the buura sacrifices as a voluntary addition that is not performed in all families.

3) Naara-bogta (naara: early millet).

Ancestral shrines in front of a compound

Before the harvesting of the early millet in July, and especially [p. 678] before the first consumption of this harvest, the first fruits must be offered to all compound shrines. On 8 July 1979, I was able to take part in such a sacrifice in Adeween Yeri. First, millet water from the previous year’s harvest was offered to the thirty-eight recipients included in the shrines. Some freshly harvested millet cobs were then held over a fire to roast them. The cobs used for this purpose must always come from the doning or nansiung field, that is, the field of the deceased or living head of the compound (yeri-nyono). Some of the resulting roasted grains were placed on the shrines of the most important ancestors, usually only on the shrines of the male ancestors in front of the compound.

4) Za-paala-bogta (sacrifice of new millet, consisting of zu-nyiam-bogta, millet water sacrifice, and sa-bogta, millet porridge sacrifice).

After the last of the early millet has been harvested (in July/August), millet water from the new harvest must be sacrificed to all of the compound shrines, followed a few days or weeks later by offerings of millet porridge (saab). Chickens and guinea fowl are also frequently sacrificed, depending on the the officiant’s wealth, but these blood sacrifices do not appear to be obligatory. At the harvest sacrifices on 28 August 1974 and 22 August 1978 at the house of Adeween Yeri, which I was able to attend, only millet water was sacrificed. The owner of the house told me, however, that he also wished to combine some blood sacrifices (of chickens) with the fiok-bogta in December as a substitute for the missing animal sacrifices of the za-paala-bogta.

For Sandema-Kalijiisa-Yongsa, my helper Sebastian Adanur was able to provide me with a list of almost all of the millet offerings (za-paala-bogta) made in 1980 (see table).

With reference to Amoanung Yeri, Abukuri Yeri and Awaanka Yeri, the table shows that several people from one household can sacrifice. This is the case when different kinship groups live in a compound with their own ancestors in front of the house and their own household management.

Before the offering of the za-paala-bogta, the inhabitants of the house may eat from the new harvest, but no stranger may be offered millet water made from it.

5) Jigsi-paala-kpaam-bogta (jigsa: shea nuts; paala: new; kpaam: oil; sacrifice of the oil of the new shea nuts).

In July/August, before butter or oil made from the newly harvested shea nuts can be consumed, the oil prepared must first be offered to the compound shrines. The shea nuts for these primitial sacrifices must be harvested from a piece of bushland belonging to an ancestor of the house. Although the offerings are made by the head of the compound (yeri-nyono), the main actors and participants are those women of the compound, who are able to make shea butter.

In those areas of Bulsaland where yams are cultivated, the oil offering can be combined with the yam offering. In Sandema-Kalijiisa, a slice of yam is placed on the sacrificial spot and oil is poured over it.

6) Ash rituals.

Scattering white ashes

After the early millet sacrifices but before the harvesting of the late millet, a male member of each compound obtains white hearth ashes from a fireplace and scatters them in small heaps at the corners of the fields and bush farms near the house. Most informants testify that these ashes are scattered directly on the ground; one informant from Sandema-Kalijiisa showed me flat stones in the fields on which the ashes were scattered. In vague statements, I was told that scattering the ashes was supposed to protect the harvest from evil spirits or witches or simply that the ashes should ensure a good harvest. Late millet harvesting may only begin, at the earliest, three days after the ashes have been scattered.

A strict distinction should be made between the scattering of ordinary white hearth ash and the application of black medicinal ash to fixed stones in the field. To produce the latter ash, certain tree roots are charred in a ngoadi (perforated earthen vessel, colander) according to the instructions of a diviner (baanoa) and then ground up and mixed with shea butter. An informant from Sandema-Kobdem reported that some of this medicine was already mixed with the seeds [p. 679] in his house after several chickens had been sacrificed over the medicine storage pot.

| Date (1980) | Compound | Sacrificer | Additional sacrifices |

| 10 August | Ataribo Yeri | Akumkadoa | dried meat (lam kosa) |

| 12 August | Aburuk Yeri | Aburuk | – |

| 15 August | Ayidoa Yeri | Anangkpieng | Two chickens |

| 17 August | Abiako Yeri | Anueka | Dried meat |

| 18 August | Amoanung Yeri | Apatanyin | Three chickens |

| 21 August | Amoanung Yeri | Akankpiewen | Two chickens |

| 23 August | Amoanung Yeri | Angaang | Dried meat |

| 3 September | Agbedem Yeri | Awoke | Dried meat |

| 5 September | Asasikum Yeri | Asasikum | Dried meat |

| 9 September | Anagunsa Yeri | Anagunsa | Dried meat |

| 12 September | Abukuri Yeri | Akangriba | – |

| 13 September | Abukuri Yeri | Akanwari | – |

| 15 September | Awaanka Yeri | Azangbabil | Three chickens |

| 17 September | Awaanka Yeri | Awudugpo | – |

| 19 September | Anagba Yeri | Aboyigpo | Four chickens |

| 21 September | Atiimbiik Yeri | Atiimbiik | – |

Before the harvesting of the late millet, a cross is marked using the black medicine on stones placed at the four corners of each field. These black medicine rites are not performed in all households and are not obligatory. However, they are known throughout Bulsaland. Their purpose is to prevent the crops from being magically taken away by an envious person (za-koosirik or za-koosidoa, literally: ‘someone who lures millet’) by saying: ‘Fi zaanga nala, yoo’ (‘Your millet is good, yoo’). The medicine is therefore also called nur-noa (literally: ‘people’s mouths’, i.e. envious statements made by others).

An informant from Fumbisi reports that the black crosses are only applied if there is a man in the compound who has fathered twins. This man draws the black crosses on the designated stones and places piles of white hearth ash beside them. If the compound does not house a father of twins, only the heaps of white ashes are placed, which can be done by anybody.

7) Kpaan-poasima-bogta (kpaama: sprouted millet, intermediate stage in the production of millet beer; poasim: to be insufficient, imperfect; poasima is meant to indicate that this is a small offering, to which guests or neighbours are not usually invited).

This sacrifice seems to be less well known in some parts of Bulsaland and is only performed, according to my informant from Sandema-Kobdem, if the deceased father of the head of the compound was a drinker or at least enjoyed drinking millet beer, but also if an exceptionally good harvest is to be expected. The millet beer offering is made before the fiok-bogta (8) to the deceased father of the yeri-nyono.

8) Fiok-bogta or fanoai-bogta (fiok or fanoai: time after the late millet harvest; end of November to December).

Paampuung clarinets blown in a duet

After the last of the late millet has been harvested, the time has come for the great sacrificial celebrations. These usually take place at the end of November or in Decmber, but they can also be delayed until January. In contrast with the earlier sacrificial celebrations, the fiok-bogta have a more public character. Friends, neighbours and relatives are invited, and in addition to millet water, several chickens and guinea fowl are almost always sacrificed, and sometimes goats, sheep or even cattle. The idea of thanksgiving (jiam teka) and the joy of the harvest is more prominent than in earlier harvest sacrifices.

[p. 680] Immediately after the first guinea corn (za-monta) is brought in, the paampung transverse clarinets are blown by the Bulsa boys. Unlike the beating of the kayagsa rattles, it should be made clear that there are no ritual reasons for this. The fact that the paampung clarinets are made from millet stalks is probably the only reason for their being played at this specific time of year.

9) Kpaan-tuok-bogta (kpaama: sprouted millet; the meaning of tuok could not be completely clarified, but it is linguistically related to toa, ‘to be hard or difficult’).

The sacrificial celebrations of the new millet beer (daam), which can take place during the dry season in January, February or March, also have a relatively festive and public character. Before the new millet beer brewed in the house is sacrificed to the compound shrines early in the morning, many neighbours, friends and relatives gather in the house to take part in the drinking parties that follow.

If asked directly about the meaning and purpose of the sacrifices of the annual ritual cycle, informants report that these are conducted to ask the ancestors and other divine powers for a good harvest (e.g. with the zabuura-nyiam-bogta) and thank them for it (most clearly with the fiok-bogta). The most important reason for most harvest sacrifices, however, seems to be the lifting of the taboo on eating the first fruits: until the first fruits have been offered to the gods, one may not enjoy any of the harvest. Most sacrifices can therefore be clearly identified as primitial. If in practice, for example, the naara-bogta are always held shortly before the start of the harvest and not shortly before the first meal of the early millet, this is probably because the harvesters like to roast and eat a few millet cobs over the fire during breaks in their work. In any case, there is no taboo on cutting millet stalks before the naara-bogta.

3. Modern influences

Modern times, with the introduction of new agricultural techniques (ploughing), increasing literacy rates and the growing influence of Christianity, have, as far as I know, had very little influence on Bulsa seasonal rites. Even many educated Christian men – including some of my informants – still perform the sacrifices in the old ways, although less important sacrifices and rites are sometimes omitted – ‘for lack of time’, as one Christian informant explained to me. At the same time, Christian churches have sought to emphasise highlights of the agricultural year through prayer and other sacred acts. In Sandema’s Presbyterian Church, after the first rainfall but before sowing, the congregation comes to the church with some of the seeds and the pastor speaks a prayer over them. After the harvest, some of the crops are brought to the church and the proceeds are distributed among the poor of the community. Christmas is also an occasion for celebration in non-Christian compounds, with millet beer, dancing, music and many visitors. In some compounds, all of the divine powers of the compound receive an offering of millet beer on Christmas Day so that they can participate in the house festivities.

The fiok harvest celebrations have recently undergone a significant but entirely profane expansion in the form of durbars, which are common throughout Ghana and beyond. Participants may meet in Bolgatanga, the capital of the Upper Region, on a large open square or in a sports stadium and compete with other tribal groups in musical performances, dances, parades, small spectacles, equestrian games, and so on. The picturesque costumes of the Bulsa war dancers, in particular, have attracted attention in many parts of Ghana, and Bulsa expatriates learn about the festivities of their tribesmen in Ghana’s north through the corresponding reports and press photographs.

[addition 2025] On the initiative of the Bulsa Youth Association, the idea of a festival for all Bulsa communities was born in the years after 1972. Under the name Fiok/Feok, it was first held in Sandema in 1974. [Cf. Matthias Apen 2015: 107-112].

[p. 681] Literature

Apen, Mathias

[addition 2025] 2015 The Feok Festival of the people of Buluk. Buluk, Journal of Bulsa Culture and Society, no 8: 107-112.

Cardinall, A. W.

1924 Division of the Year Among the Talansi of the Gold Coast. Man 24: 61–63.

Delafosse, M.

1921 L’annee agricole et le calendrier des Soudanais. L’Anthropologie 31: 105–113.

Fortes, Meyer

1936 Ritual Festivals and Social Cohesion in the Hinterland of the Gold Coast. American Anthropologist 38: 590–604.

1945 The Dynamics of Clanship Among the Tallensi. London, New York, Toronto: Oxford University Press.

van Gennep, A.

1909 Les rites de passage. Etude systematique des rites. Paris.

Heermann, Ingrid

1981 Subsistenzwirtschaft und Marktwirtschaft im Wandel. Wirtschaftsethnologische Forschungen bei den Bulsa in Nord-Ghana. Hohenschäftlarn: Klaus Renner Verlag. (Kulturanthropologische Studien, 2.)

Kröger, Franz

1978 Übergangsriten im Wandel. Kindheit, Reife und Heirat bei den Bulsa in Nord-Ghana. Hohenschäftlarn: Klaus Renner Verlag. (Kulturanthropologisehe Studien, 1.)

1980 The Friend of the Family or the Pok Nong Relation of the Bulsa in Northern Ghana. Sociologus 30 (2): 153–165.

1982 Ancestor Worship Among the Bulsa of Northern Ghana. Religious, Social, and Economic Aspects. Hohenschäftlarn: Klaus Renner Verlag (Cultural and Anthropological Studies, 9).

[addition 2025] 1984 The Notion of the Moon in the Calendar and Religion of the Bulsa (Ghana). Systèmes de Pensée en Afrique Noire 7: 149–151.

Rattray, R. S.

1932 The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland. 2 vols. London: Oxford University Press.

Riehl, Volker

[addition 2025] 1993 Natur und Gemeinschaft. Sozialanthropologische Untersuchungen bei den Tallensi in Nord-Ghana. Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, New York, Paris, Vienna (Soziologie und Anthropologie, 9).

Schott, Rüdiger

1966/67 Unpublished field notes.

1970 Aus Leben und Dichtung eines westafrikanischen Bauernvolkes. Ergebnisse völkerkundlicher Forschungen bei den Bulsa in Nord-Ghana 1966/67. Köln und Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

1977 Sources for a History of the Bulsa in Northern Ghana. Paideuma 23: 141–168.

Schweeger-Hefel, Annemarie and Wilhelm Staude

1967 Agrarsymbolik und Agrarkalender der Kurumba (Haute Volta). Paideuma 13: 164-179.

Vorbichler, A.

1956 Das Opfer auf den uns heute noch erreichbaren ältesten Stufen der Menschheitsgeschichte. Eine Begriffsstudie. Mödling bei Wien: St. Gabriel-Verlag.

Zwernemann, Jürgen

1968 Die Erde in Vorstellungswelt und Kultpraktiken der sudanischen Völker. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag.

- The Permanent Establishment of Ritual Deviations (German original version 2012)

- Bulsa Rites of Passage (English Version)

- Title, Contents and Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter I: Pregnancy

- Chapter II: Birth

- Chapter III: The Guardian Spirit, Naming and Names

- Chapter IV: Scarifications

- Chapter V: Wen Rites

- Chapter VI: Excision and Circumcision

- Chapter VII: Courting and Marriage

- Chapter VIII: Death and Burial

- Chapter VIII (contd.): Funeral Celebrations

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Übergangsriten im Wandel, Deutsche Version (1978)

- Titel, Vorwort, Inhalt, Einleitung

- Schwangerschaft und Geburt

- Namensgebung und Namen

- Skarifizierungen

- Wen-Riten

- Beschneidungen

- Brautwerbung und Ehe

- Tod, Trauer und Bestattung (1. Teil)

- Tod und Bestattung (2.Teil)

- Die Kumsa Totenfeier

- Die Juka Totenfeier

- Schluss

- Anhang

- Literaturverzeichnis

- Gesamtedition der Übergangsriten

- Buli Language Guide (2020)

- Buli Names

- The Bulsa Educational Elite… Discussions in a Facebook Group (German original version 2022)

- The English and American Image of Germany in the Past

- The Ritual Calendar of the Bulsa (German original version 1986)

- Evil in the Divine Being (German original version 2013)

- Black Crosses and Divinatory Objects (German original version 1992)

- Traditional and School-Based Education among the Bulsa

- Bulsa Divination und Wahrsager

- Historical Sources