Adapted and translated from F. Kröger: Schwarze Kreuze und Wahrsagerobjekte: tote und lebende Symbole der Bulsa, in: Sprache, Symbole und Symbolverwendungen in Ethnologie, Kulturanthropologie, Religion und Recht. Festschrift für Rüdiger Schott zum 65. Geburtstag, ed. W. Krawietz, L. Pospisil and S. Steinbrich. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Parenthetical numbers such as [94] refer to page numbers in the original German version. The photographs were taken between 1973 and 2011 and inserted into the text in 2025.

Franz Kröger

Black Crosses and Divinatory Objects: Dead and Living Symbols of the Bulsa

Ethnographic introduction: The Bulsa, an ethnic group of around 60,000–70,000 members, live in northern Ghana, not far from the border with Burkina Faso, in an acephalous society with patrilineal succession. They earn their living mainly through agriculture, which is practised almost exclusively for subsistence. In addition, they keep cattle, sheep, goats, chickens and a few other animal species. Their religious world view is determined by their belief in a sky god and by the cultic worship of the earth, the ancestors and some spiritual beings. The Bulsa have only relatively recently become the subject of ethnographic research. Before R. Schott’s first field research stay in 1967/68, aside from fairly brief, sometimes scattered contributions by R. S. Rattray (1932), A. W. Cardinall (1920?) and L. Tauxier (1912 and 1924), few publications on the Bulsa had appeared. More recent ethnographic literature concerning this ethnic group has been published, for the most part, by Schott and his students, including the author of the present work.

This work seeks to examine some pictorial symbols and symbolic actions that appear almost daily in the secular and religious life of the Bulsa: it considers how far their meaning is known to those who use them and to what extent they remain sufficiently ‘alive’ and flexible in their application that they can be adapted to changing situations spontaneously and without loss of value. Only symbolic complexes whose meanings are consciously understood by users in every respect can be detached from traditional sequences of actions, incorporated into new structures of meaning and expanded through the analogous formation of new series of symbols. Because of their great variability, dynamism and adaptability, the symbols that make up such complexes are referred to as living symbols. These are contrasted with ‘dead’ symbols (endnote 1), which have been handed down in an ossified form from ancient times to the present day without today’s practitioners’ being able to explain the relationship between their form and their message. Their earlier meanings can, however, be the subject of extensive hermeneutic research [94] today, and here, the foreign ethnologist is confronted with difficulties qualitatively similar to those experienced by the insider striving for a deeper understanding of their own culture. Users of such symbols who assume that the latter have some meaning unknown to them can often only answer the researcher’s inquiries by relying on tradition (‘Our ancestors always did it this way’), a form of response which usually does not satisfy the questioner.

Among the Bulsa, for example, many ritual structures and most of the decorative pictorial elements found on houses and pots belong to the group of dead symbols. In the case of the decorative elements, it is even doubtful whether and to what extent zigzag lines, semicircles, wavy lines, knobs, and so forth ever had a meaning – that is, whether they were ever real, living symbols to the Bulsa or arose only from aesthetic and playful motivations. In contrast to the stylistic elements employed by potters, blacksmiths can usually still interpret the signs they use, which are often taken from the astral realm. A zigzag line, for example, represents a flash of lightning that can hurl meteorites to earth. A simple rhombus is a star, and a rhombus with many small dots indicates the constellation of the Pleiades (in Buli, the language of the Bulsa: chiisa ma, ‘mother of the chicks’), with its significance for the ritual year. These interpretations should not, however, be applied to other areas of Bulsa culture, especially since the lineages from which blacksmiths originate belong to a separate immigration and settlement layer (see also Schott 1983: 310ff.).

Hair pattern

Drawing a Greek cross at an entrance

Navel incisions

From the large group of dead symbols, that of the equal-armed ‘Greek’ cross will be examined here in somewhat greater detail. There is certainly no modern influence from Christianity here, especially since the first significant contact between the Bulsa and Christians did not take place until the 1920s. The equal-armed cross appears among the Bulsa in several variant forms: the point of intersection of the two crossbars can be marked or unmarked, the arms can each consist of one or more parallel lines and the cross can be found with or without a surrounding circle. This symbol is used in a wide variety of areas of life. When a child is born, a specialist prepares a black med icine with which he anoints the mother and child and then draws Greek crosses above the entrance to the delivery room, on the grain store and at the exit of the courtyard. This practice is intended to protect the vulnerable lives of the mother and child from a range of malevolent external influences. If the infant dies, the mother’s hair is shaved off; [95] in some parts of the Bulsaland, two intersecting stripes are later shaved into the regrowing hair.

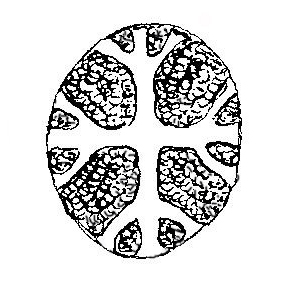

If the child survives and experiences certain symptoms of abdominal illness at a young age, several incisions around 10 centimetres long are subsequently cut around their navel (endnote 2). Often, three incisions are made above, below, to the right and to the left of the navel with a razor blade, again creating a Greek cross. To protect a crop from theft and evil supernatural influences, in some Bulsa villages, flat stones are placed at the four corners of the field and a particular charred ‘medicine’ (tiim) is used to draw black crosses on them (endnote 3). In other parts of the Bulsa region, only the drawing of a black ash cross on a calabash shard hung in the field is known as a form of protection against theft. When the granary of the head of a compound is built in the cattle yard, its raised stone foundation is plastered with damp clay by the mason. He then presses a round stone into the centre of thiscircular surface. Starting from this point, with the fingers of his right hand, he draws bundles of lines from the central stone to the edges of the circle to form a cross. A Greek cross in a circle or alone can also occasionally be seen in the form of a bas-relief at the entrance to a compound. Lastly, it can sometimes be found on larger pots, outside the decorative bands and only slightly integrated into the overall ornamentation.

Drawing a cross on the bottom of a grainstore

A cross on a ceramic vessel

Symbolic object for a crossroads

In all of these cases, the users of this cross symbol could not provide any interpretation of its meaning but were content with the tradition-based explanation mentioned above. A compound head who had placed a roughly one-metre-tall bas-relief Greek cross in the clay of the compound wall next to the entrance attempted to provide an explanation in English: ‘All evil must pass up, down, side [sideways] and side off [to the other side] forever’. At first glance, this interpretation does not seem very helpful, especially since the informant’s way of thinking had already been influenced by a European-oriented education. Nevertheless, one essential aspect seems logical, namely the understanding of the cross’s arms as direction indicators, which also applies to the symbol’s use in other contexts. The length of the arms is unimportant to such an interpretation, and the symbol can be associated with actions and images in which only the four directions – at right angles to one another and starting from a common centre – play a role. These include the crossroads, which [96] plays an important role in the ritual life of the Bulsa as a place for sacrifices of various kinds. If a diviner (baanoa, pl. baanoaba) prescribes a sacrifice at a crossroads, the diviner’s rod (baan duok), his most important tool, points to a symbolic object from his diviner’s bag, usually a round or triangular calabash shard with an incised cross. For this purpose, the diviner can also draw a Greek cross on the ground with his rod and perhaps indicate with a dot exactly where the sacrifice should take place.

There is also a group of sub-rites in which actions are performed in four directions from a central point that could be associated with the cross symbol. Chief among these is the gaasika, a ritual in which a food taboo is lifted after a life crisis by the affected person’s taking the hitherto forbidden food in their mouth and spitting it in four different directions (forwards, right, backwards and left). A similar action is performed in the cleansing ritual of the pursika, in which an oath or malicious false testimony is undone by spitting out water four times.

Among the Bulsa, apart from vague allusions from some informants, no clear explanations have been given for the origin or nature of these rituals related to four directions. Just as with the pictorial representations of the cross, often, only the purpose of the entire ritual complex is known. For example, the Greek cross, painted with black medicine, must help to avert danger. The actual defensive factor in the practitioner’s mind, however, is more the magical effectiveness of the medicine and the symbolic power of the black ash, which is produced, for example, by charring certain pieces of root. In other applications, no conscious function is ascribed to the cross shape (e.g. crosses on ceramic vessels or on the floor of a grain store), or other explanations, unhelpful for our purposes here, are supplied. Thus, for example, umbilical incisions are intended to prevent an evil spirit that causes abdominal pain from recognising its victim on its next visit. Research to date thus indicates that among the Bulsa, knowledge of the origin, meaning and symbolic value of the Greek cross and associated symbols across various areas of application is almost completely absent or, indeed, lost.

This examples of a dead symbols are to be contrasted with a complex of pictorial symbols that are in many respects alive, in which (1) the relationship between the images and their symbolic content is completely unambiguous and clear, (2) the same symbol has the same meaning in different areas of application and (3) new symbolic relationships can be constantly established by analogy with existing [97] image–content relations.

Akanming’s divination session

This category can be illustrated with the help of the symbolic objects used by a traditional Bulsa diviner in his sessions with clients (endnote 4). The diviner plays a central role in the Bulsa religious–ritual system. His task is not so much prophecy as the interpretation of extraordinary events in the past (illnesses, misfortunes, losses, etc.) and the provision of ritual instructions to make amends for wrongdoings and omissions. According to Bulsa beliefs, however, the diviner does not analyse the past or explore the wishes of an angry deity or spirit directly. Throughout the session, the diviner acts rather as an instrument of his divining spirit (jadok), which he summons by shaking a calabash rattle. When it appears from its roof-shrine, it moves through the rattle and the body of the diviner (who flinches slightly) into the divination rod and subsequently answers the questions of the client through the movements of this rod. To enable the silent conversation between jadok and client, three symbolic methods are available, each of which alone would be sufficient to express all of the desired thoughts and instructions:

Two iron disks for the binary method

1. Two flat granite stones or iron discs in the centre of the divination room are used by the client for expressing opposing answers to his questions to be asked; for example, the left stone may mean ‘true, applicable, yes’ and the right stone ‘untrue, not applicable, no’. When the client asks a question, the diviner holds the upper end of his divining rod on a small forked branch while the client holds the lower end, and the rod, unerringly guided by the jadok, points to one of the stones or discs. With the help of this binary method, all areas of human life can be covered by asking suitable questions that start with broad categories and then break them down into ever smaller units. After a loss of money, for example, the client might ask the following questions: ‘Was the money stolen?’ (The rod strikes the left disc: yes!); ‘Does the thief come from outside my compound?’ (No!); ‘Is it one of my wives?’ (Yes!); ‘Is it my youngest wife?’ (Yes!).

2. The rod answers without reference to a special divination tool, for example, by drawing symbols on the floor or pointing to elements of the divination room and its objects and arrangements, which are then reinterpreted [98] as symbols. If the rod points to the entrance to the room, for example, this can mean that a danger is coming from outside, that is, from a stranger or a member of another clan section. Here, we find a twofold reinterpretation. The real object, the entrance to the divination room, is equated with the entrance to the client’s compound. The entrance in general also serves as a symbolic dividing line between two social units, namely one’s own extended family and the groups outside one’s compound.

In this (second) method, the client’s body, in particular, becomes a symbolic landscape for the divining rod. Innumerable thoughts and prompts can be expressed simply through the various parts of the body. Of the 53 collected symbolic movements of the rod and its reinterpretations of body parts and objects that are not specifically tools of the diviner, a few examples are given here to clarify the point:

a) The rod points to parts of the client’s body. These have the following meanings:

Head (zuk): something is bothering or confusing the person concerned;

Back of the head: the problem continues to haunt you (ku bo fi ngaang);

Ears (tue): listen carefully (wom!);

Cheek (chikperi): you will laugh and be successful (symbolic value: laata, laughter);

Eyes (nina): keep your eyes open (lag fi nina!);

Mouth (noai): food (ngan-diinta) or speaking (biik);

Beard (tieng): a man (nuru); also: father (ko);

Neck (ngiri): people outside your own family; stroking the neck: why aren’t you wearing your neck amulet?;

Throat (loeluk): if evil is not eliminated, death will occur;

Armpit (buluk): hidden things;

Shoulder (ngmangkpaluk): natural father (ko-biamu); a father carries an infant on his shoulder, not on his back);

Hand (nisa po, literally ‘into the hand’): for example, someone is handing you something; gifts;

Finger (nandub): illness (nying-tuila);

Back (ngaang): people stab you in the back, blackmail you;

Chest (rod hits the chest): luck (popienta);

Nipples (here known as biisa, ‘female breasts’): it is a woman (nipok);

Belly: pregnancy (puuk); but also: stomach-ache (poi-domsik);

Navel (siuk): natural brother or sister;

Knees (dunung): you must kneel and ask for forgiveness; [99]

Penis (yoari): (forbidden) sexual intercourse (kabong);

Feet (nangsa): reference to a journey (chelim).

b) The divining rod moves freely or draws symbols:

Scratching on the ground (grinding movement): millet water (zu-nyiam);

Small circular movement (gilim): (sacrifice of) millet porridge (saab);

Large circular movement: the problems are encircling you, that is, they are not yet solved;

Straight line on the ground: sacrifice by a footpath (siuk);

Greek cross (ja-barim): sacrifice at a crossroads (siuk-pak);

Zigzag line on the ground: written matters (ngmarisika), e.g. court, school, authorities; letter;

Rod held flat on the ground: the sacrificed animal is to be roasted (no millet porridge is served with it);

Rod pointing to the door: external affairs (see above); or: the client and his companion should speak outside;

Rod pointing at the diviner: consult the two discs (see above);

Rod hitting the ground: earth, earth deity, earth sanctuary (teng, tanggbain);

Rod pointing upwards: heaven, sky deity (wen, naawen);

Rod drawing lines on the ground: time units, e.g. in days (chiim da, ‘count the days’) or months (chiim chiisa).

Many other possibilities for such silent expression are created spontaneously, and the category can hardly be grasped here in its entirety.

Symbolic objects attached to sticks

3. The rod points to explicitly symbolic objects spread out for divination. Although the diviner can do without his goatskin bag and its numerous (approx. 50–150) symbolic objects when dealing with simple problems, such as the illness of a client’s family member, the full range of possibilities for dialogue between a client and the jadok spirit acting through the divining rod is only possible after the contents of the bag have been spread out. Some of the symbolic objects are specially made for the divination process, such as calabash shards cut to size and partly marked with incisions; most such objects are attached to millet stalks around 30 cm long.

Another group of objects consists of fragmentary or complete utensils from daily life and animal body parts. Most objects have two Buli names. The first describes the external form of the object or is its name from the non-ritual, functional domain. The second refers to its symbolic value and can, as such, already contain an order, threat or promise in response to the client’s question. Of approximately 1,560 objects examined from the skin bags of various diviners [100] some are presented here as examples, with the external description of the object given first and the corresponding symbolic value (SV) second:

1. Calabash seeds strung on a cord (chin-poa bie or kalsa); SV: bisa (children), you will have many children; or: all descendants of an ancestor. As in birth, the calabash seeds are removed from something previously closed. Linguistically, the terms biri (root *bi), ‘core’, and biik (pl. bisa, root *bi), ‘child’, are undoubtedly related.

Chin-poa or kalsa |

Chiiri |

Chiik |

Buuk nang |

Kanbieng |

Miik |

Naab gbain gelik |

Ninang biri le voana |

Kpiak chakobi |

2. A piece of slag (chiiri); SV: bolim (fire), this is a dangerous (‘hot’) affair. The symbolic value of ‘fire’ alludes to the heated state of this object during the smelting process.

3. A moon-shaped piece of calabash (chiik); SV: chiik (moon, month), you must make a moon amulet; or: in the course of a month.

4. Loose goat’s foot (buuk nang); SV: dung (animal) or dung kaabka (animal sacrifice), you must sacrifice an animal (cow, sheep or goat).

5. Small glass medicine bottle (koalini); SV: felika wari (white man’s business), for example, take the sick person to the White Fathers’ infirmary.

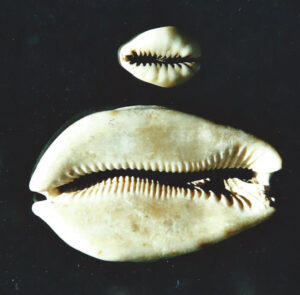

6. Conch shell (kambieng); SV: nying-yogsa (health), the sick person will get well. The shell was once in cool water; coolness is associated with health (nying-yogsa, literally ‘cool body’).

7. One or two twisted cords (miik); SV: ko-biamu (natural father). The ancestors strangle their descendants with ropes if they do not fulfil their will.

8. Cloth shred (garu-chiak): SV: kpio(k), a dead person for whom no funeral has yet been held. The shred represents the triangular cloth (golung) worn by a dead person in the grave. The triangular hip cloth stands as pars pro toto for the dead person.

9. A piece of cowhide (naab gbain gelik); SV: jigsika (wealth), you will acquire wealth, you will live like a chief. [101] A cowhide is a kind of throne, on which a chief sits at his enthronement (enskinment).

10. An empty corn cob (cholimbein); SV: ngan-diinta (food), you must sacrifice millet water; or: you will have plenty of food. It seems strange that an empty corn cob symbolises millet (or millet water sacrifice). As an explanation, it is said that the thinner millet cobs easily break among the many stones and iron objects in the bag.

11. A small pencil end (pencil); SV: ngmarisika (the written word), dealing with state authorities, schools, courts; or: a letter has arrived (or will arrive).

12. Fruit of the ninang tree (Sclerocarya birrea) with two holes (ninang biri le voana); SV: nyuvuri (literally ‘breathing nose’), long life. The two naturally occurring holes in the fruit are associated with the nostrils of a human being. The nose, in turn, is a respiratory organ, a symbol of long life.

13. A piece of bone from the spine of a chicken (kpiak chakobi); SV: segrika (special ritual), a segrika naming ritual must be performed for the child. Although a chicken or rooster is always sacrificed during the segrika, this does not appear to be the sole and complete reason for the very specific form of the bone as a symbol for a naming ritual.

14. A small stone (tintain); SV: teng (earth sanctuary, earth).

15. A piece of a tree root (tinang); SV: root medicine (tinang) or medicine (tiim), medicine for a specific illness must be prescribed; or: the medicine shrine demands a sacrifice.

As these explanations of the objects and their symbolic values show, there is usually a conceptual connection between object and symbol; the nature of this connection, however, varies:

1. The object bears a similarity to its symbolic meaning in one or more of its properties (1, 9, 10, 12).

2. The symbol’s name alludes to an earlier state of the object (2, 6).

3. The object has been consciously produced as a simplified image (3).

4. The concept symbolised includes actions or states that the object can perform or bring about (7, 9, 11). This group includes the numerous threats and promises [102] that relate to compliance or non-compliance with the instructions given.

5. A pars-pro-toto relationship exists between the object and the concept symbolised (4, 5, 8).

6. The object and the symbol are almost the same (15: root of a tree for root medicine), that is, the symbolic span is very small.

7. No relationship between object and symbolic value is recognisable or ascertainable (13). This is rare.

As the list above shows, polyvalent interpretations are admissible for symbolic objects (see nos. 3, 10, 11, 15). Occasionally, an object can lose almost all symbolic value and be used to represent its basic, literal meaning. A wooden yarn roll (gunggong, literally ‘hourglass drum’) can, theoretically speaking, even be used in a single session to indicate the meanings ‘journey’ (chelim), ‘lorry’, ‘hourglass drum’ (gunggong) and ‘yarn roll’.

Only very late in my research was I able to learn that some regularly returning clients may also be represented by characteristic symbolic objects in the divination bag. The diviner Akanming, for example, has given some objects an additional symbolic meaning in relation to those fellow diviners who are his clients. This does not refer directly to the individual, however, but to their divination spirit (jadok). A piece of a bicycle chain, for example, which otherwise has the symbolic value kpiesa (shackle, the ancestors will shackle you and paralyse you in your actions), simultaneously denotes the jadok spirits of the diviners Atingkpi and Angmariwen. These diviners’ ngandoksa (pl. of jadok) revealed themselves a long time ago in the form of a snake (waab). Akanming therefore associated the ‘snakelike’ bicycle chain with their forms. For me, Akanming selected a glazed, hard-fired ceramic shard already imbued with the symbolic value pagrim (strength). The diviner, who was probably over 70 years old, still associated strength and power with the white man. It was probably also significant, however, that this shard had been part of an imported vessel, perhaps one made in Europe (the Bulsa are not able to produce stoneware and glazes). According to the criteria established here, a diviner can always create new symbols that have not yet been used in this form in any other divination process by him or another diviner. Imported products from industrialised countries and waste products from disused bicycles, bent nails, plastic objects, toys, and so on can also become part of the repertoire as soon as the diviner has found a suitable application. [103]

The range and freedom available in the creation and application of new symbolic objects is demonstrated by the fact that an idea or concept for which there is a certain demand in a divination session can be represented by a wide variety of objects. To represent the idea of ‘beauty’ (nalim), for example, the diviners in my circle of informants had chosen ten different objects, as the following list, including the names and (in parentheses) residences of the diviners shows:

1. A small red fibre tuft: Akai (Wiaga-Badomsa);

2. A piece of red cloth: Akanming (Wiaga-Badomsa), Akannagayiri (Wiaga-Wabilinsa), Akantoganya (Wiaga-Goldem);

3. A red piece of plastic film: Aleesinoai (Wiaga-Chiok), Anaglalie (Wiaga-Chiok), Ayaya (Wiaga-Sichaasa);

4. A Rosetta bead (nabiin-soruk biri): Abagduok (Wiaga-Badomsa), Akai (Wiaga-Badomsa), Akannagayiri (Wiaga-Wabilinsa), Aleesinoai (Wiaga-Chiok), Asiakperik (Wiaga-Badomsa), Ayaya (Wiaga-Sichaasa; a complete string), Ayomo Ayuali (Wiaga-Badomsa), Azong (Wiaga-Yisobsa);

5. A brown-red bead: Ayaya (Wiaga-Sichaasa);

6. A cowrie shell (ligri, for other diviners, this has only the meaning of ‘money’ or ‘eye’): Asiakperik (Wiaga-Badomsa);

7. A divination rod made of aluminium wire of the same length as the millet rods: Abagduok (Wiaga-Badomsa);

8. A green plastic ball: Atiim (Wiaga-Badomsa);

9. A shiny metal belt buckle: Akannagayiri (Wiaga-Wabilinsa);

10. A corner piece of a kapok fruit: Akannagayiri (Wiaga-Wabilinsa).

Nabiin soruk biri |

Ligri |

Kapok |

A large proportion of the symbolic objects, however, are the same or at least very similar among all Bulsa diviners; it would otherwise be very difficult for clients to understand the messages of previously unfamiliar diviners and their ngandoksa. Even given these circumstances, the client always interprets the symbolic objects as a control measure. When the rod points to an object, the client responds with a verbal interpretation, such as ‘N ko-biamu le nna’ (‘This is my biological father’) or ‘Kpiaka le nna’ (‘This is the chicken’). The speed and fluency with which most clients make these interpretations prove how far, after countless sessions, they have penetrated the symbolic world of the diviners. The diviner must sometimes [104] correct an interpretation, or the client may ask, ‘Boan le nna?’ (‘What does this mean?’). Nonetheless, often, almost an entire session can pass without any dialogue between the diviner and his visitor, since the latter has fully grasped the network of relationships between objects and symbolic content. The final explanations of the diviner regarding the results of the inquiry can thus be very brief. The Bulsa diviner merely makes his numerous symbolic objects available to his client, invokes his jadok spirit, who, according to Bulsa belief, induces the correct selection of symbolic objects, and helps the visitor – if necessary – to interpret the symbols.

It is left to the discretion of clients how much insight into their personal problems they allow the diviner, such as by mentioning names from within their families. Especially when a client comes from a neighbouring ethnic group with a similar system of divination (endnote 5) and diviner and client can only communicate with difficulty because of their different languages, it may occur that the client receives satisfactory answers from the divination session, but the diviner himself remains unaware of exactly what problems his client came to him with. Of the two symbolic systems that can otherwise play a more or less important role in a divination session, namely the imaginative system of the divination symbols and the discursive system of human language, only the first is fully functional here, but it proves fully sufficient for successful communication in the sense of addressing the client’s concern.

At this point, the apparent problem of the coexistence of dead and living symbols within an ethnic group can be resolved to a certain extent. Although it is in the nature of symbols to establish communication between two parties, dead and living symbols differ in the entities with which they are used to communicate. Bulsa divining symbols, like the symbolic system of language, enable communication between two or more living individuals. For this purpose, new symbols must constantly be created to encompass all possible situations in a society that is forever changing due to the influences of acculturation. Dead symbols, conversely, are directed primarily at supernatural powers, be those helpful deities or evil spirits, who understand the symbolic content of a black cross even when this is no longer known to the human user. This one-sided lack of knowledge has no negative influence on the success of the communication attempt, as can be seen, for example, when symbols are embedded in ritual actions; on the contrary, the incomplete insight on the part of the human user elevates the symbolic ritual [105] from the realm of purely human communication and surrounds it with a sacred esotericism. The message conveyed to the selected supernatural powers is understood and interpreted by them in the same way in which the divination symbols are interpreted by the client of a diviner.

Endnotes

(endnote 1) The symbols designated here as ‘dead’ correspond, in part, to the ‘arbitrary symbols’, a term used by C. H. Winick (1977: 519). The terms ‘living’ and ‘dead’ are preferred in this paper to acknowledge the fact that the ‘dead’ symbols discussed here all experienced a living stage at some point.

(endnote 2) For a more detailed account, see Kröger 1978: 127–128.

(endnote 3) See also Kröger 1986: 678–689.

(endnote 4) Since a more comprehensive work is planned on diviners and divination techniques among the Bulsa, detailed descriptions of other aspects of this topic (such as the characteristics and workings of the jadok spirit, the initiation of diviners and economic and social implications) will be treated only briefly or not at all here.

(endnote 5) Here, the Kasena deserve particular mention (see also Zwernemann 1964).

Bibliography

Cardinall, A. W. (1920), The Natives of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast. Their Customs, Religion and Folklore, New York: Negro University Press.

Kröger, Franz (1978), Übergangsriten im Wandel. Kindheit, Reife und Heirat bei den Bulsa in Nord-Ghana, in: R. Schott and G. Wiegelmann (Eds.), Kulturanthropologische Studien, Bd. 1, Hohenschäftlarn: Renner Verlag.

(1982), Ancestor Worship among the Bulsa of Northern Ghana. Religious, Social and Economic Aspects, in: R. Schott and G. Wiegelmann (Eds.), Kulturanthropologische Studien, vol. 9, Hohenschäftlarn: Renner Verlag.

(1986), Der Ritualkalender der Bulsa (Nordghana), in: Anthropos 81, pp. 671–681.

(1992), Buli-English Dictionary. With an Introduction into Buli Grammar and an Index English-Buli, Münster/Hamburg: Lit Verlag.

Rattray, R. S. (1932), The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland, 2 vols., London: Oxford University Press.

Schott, Rüdiger (1970), Aus Leben und Dichtung eines westafrikanischen Bauernvolkes. Ergebnisse völkerkundlicher Forschungen bei den Bulsa in Nord-Ghan 1966/67, in: Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Forschung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen, Geisteswissenschaften, 163, Cologne/Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

(1977), Sources for a History of the Bulsa in Northern Ghana, in: Paideuma 23, pp. 141–168.

(1983), Glaube und Brauch der Schmiede bei den Bulsa in Nord-Ghana, in: H. P. Duerr (Ed.), Sehnsucht nach dem Ursprung. Zu Mircea Eliade.

Tauxier, Louis (1912), Le noir du Soudan – Pays Mossi et Gourounsi, Paris.

(1924), Nouvelles notes sur le Mossi et le Gourounsi, Paris.

Winick, Charles (1977), Dictionary of Anthropology, Totowa, New Jersey.

Zwernemann, Jürgen (1964), La divination chez les Kasena de Haute-Volta, in: Notes Africaines IFAN 102, pp. 58–61.

- The Permanent Establishment of Ritual Deviations (German original version 2012)

- Bulsa Rites of Passage (English Version)

- Title, Contents and Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter I: Pregnancy

- Chapter II: Birth

- Chapter III: The Guardian Spirit, Naming and Names

- Chapter IV: Scarifications

- Chapter V: Wen Rites

- Chapter VI: Excision and Circumcision

- Chapter VII: Courting and Marriage

- Chapter VIII: Death and Burial

- Chapter VIII (contd.): Funeral Celebrations

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Übergangsriten im Wandel, Deutsche Version (1978)

- Titel, Vorwort, Inhalt, Einleitung

- Schwangerschaft und Geburt

- Namensgebung und Namen

- Skarifizierungen

- Wen-Riten

- Beschneidungen

- Brautwerbung und Ehe

- Tod, Trauer und Bestattung (1. Teil)

- Tod und Bestattung (2.Teil)

- Die Kumsa Totenfeier

- Die Juka Totenfeier

- Schluss

- Anhang

- Literaturverzeichnis

- Gesamtedition der Übergangsriten

- Buli Language Guide (2020)

- Buli Names

- The Bulsa Educational Elite… Discussions in a Facebook Group (German original version 2022)

- The English and American Image of Germany in the Past

- The Ritual Calendar of the Bulsa (German original version 1986)

- Evil in the Divine Being (German original version 2013)

- Black Crosses and Divinatory Objects (German original version 1992)

- Traditional and School-Based Education among the Bulsa

- Bulsa Divination und Wahrsager

- Historical Sources